Heroes and Villains in Uruguayan Soccer (2010-2014): a Discursive Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Semanal FILBA

Ya no (Dir. María Angélica Gil). 20 h proyecto En el camino de los perros AGENDA Cortometraje de ficción inspirado en PRESENTACIÓN: Libro El corazón y a la movida de los slam de poesía el clásico poema de Idea Vilariño. disuelto de la selva, de Teresa Amy. oral, proponen la generación de ABRIL, 26 AL 29 Idea (Dir. Mario Jacob). Documental Editorial Lisboa. climas sonoros hipnóticos y una testimonial sobre Idea Vilariño, Uno de los secretos mejor propuesta escénica andrógina. realizado en base a entrevistas guardados de la poesía uruguaya. realizadas con la poeta por los Reconocida por Marosa Di Giorgio, POÉTICAS investigadores Rosario Peyrou y Roberto Appratto y Alfredo Fressia ACTIVIDADES ESPECIALES Pablo Rocca. como una voz polifónica y personal, MONTEVIDEANAS fue también traductora de poetas EN SALA DOMINGO FAUSTINO 18 h checos y eslavos. Editorial Lisboa SARMIENTO ZURCIDORA: Recital de la presenta en el stand Montevideo de JUEVES 26 cantautora Papina de Palma. la FIL 2018 el poemario póstumo de 17 a 18:30 h APERTURA Integrante del grupo Coralinas, Teresa Amy (1950-2017), El corazón CONFERENCIA: Marosa di Giorgio publicó en 2016 su primer álbum disuelto de la selva. Participan Isabel e Idea Vilariño: Dos poéticas en solista Instantes decisivos (Bizarro de la Fuente y Melba Guariglia. pugna. 18 h Records). El disco fue grabado entre Revisión sobre ambas poetas iNAUGURACIÓN DE LA 44ª FERIA Montevideo y Buenos Aires con 21 h montevideanas, a través de material INTERNACIONAL DEL producción artística de Juanito LECTURA: Cinco poetas. Cinco fotográfico de archivo. LIBRO DE BUENOS AIRES El Cantor. escrituras diferentes. -

Fis Hm an Pele, Lio Nel Messi, and More

FISHMAN PELE, LIONEL MESSI, AND MORE THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PELE, LIONEL MESSI, AND MORE JON M. FISHMAN Lerner Publications Minneapolis SCORE BIG with sports fans, reluctant readers, and report writers! Lerner Sports is a database of high-interest LERNER SPORTS FEATURES: biographies profiling notable sports superstars. Keyword search Packed with fascinating facts, these bios Topic navigation menus explore the backgrounds, career-defining Fast facts moments, and everyday lives of popular Related bio suggestions to encourage more reading athletes. Lerner Sports is perfect for young Admin view of reader statistics readers developing research skills or looking Fresh content updated regularly for exciting sports content. and more! Visit LernerSports.com for a free trial! MK966-0818 (Lerner Sports Ad).indd 1 11/27/18 1:32 PM Copyright © 2020 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Lerner Publications Company A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com. Main body text set in Aptifer Sans LT Pro. Typeface provided by Linotype AG. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Fishman, Jon M., author. Title: Soccer’s G.O.A.T. : Pele, Lionel Messi, and more / Jon M. -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

Goal Celebrations When the Players Makes the Show

Goal celebrations When the players makes the show Diego Maradona rushing the camera with the face of a madman, José Mourinho performing an endless slide on his knees, Roger Milla dancing with the corner flag, three Brazilians cradling an imaginary baby, Robbie Fowler sniffing the white line, Cantona, a finger to his lips contemplating his incredible talent... Discover the most fantastic ways to celebrate a goal. Funny, provo- cative, pretentious, imaginative, catch football players in every condition. KEY SELLING POINTS • An offbeat treatment of football • A release date during the Euro 2016 • Surprising and entertaining • A well-known author on the subject • An attractive price THE AUTHOR Mathieu Le Maux Mathieu Le Maux is head sports writer at GQ magazine. He regularly contributes to BeInSport. His key discipline is football. SPECIFICATIONS Format 150 x 190 mm or 170 x 212 mm Number of pages 176 pp Approx. 18,000 words Price 15/20 € Release spring 2016 All rights available except for France 104 boulevard arago | 75014 paris | france | contact nicolas marçais | +33 1 44 16 92 03 | [email protected] | copyrighteditions.com contENTS The Hall of Fame Goal celebrations from the football legends of the past to the great stars of the moment: Pele, Eric Cantona, Diego Maradona, George Best, Eusebio, Johan Cruijff, Michel Platini, David Beckham, Zinedine Zidane, Didier Drogba, Ronaldo, Messi, Thierry Henry, Ronaldinho, Cristiano Ronaldo, Balotelli, Zlatan, Neymar, Yekini, Paul Gascoigne, Roger Milla, Tardelli... Total Freaks The wildest, craziest, most unusual, most spectacular goal celebrations: Robbie Fowler, Maradona/Caniggia, Neville/Scholes, Totti selfie, Cavani, Lucarelli, the team of Senegal, Adebayor, Rooney Craig Bellamy, the staging of Icelanders FC Stjarnan, the stupid injuries of Paolo Diogo, Martin Palermo or Denilson.. -

2016 Panini Flawless Soccer Cards Checklist

Card Set Number Player Base 1 Keisuke Honda Base 2 Riccardo Montolivo Base 3 Antoine Griezmann Base 4 Fernando Torres Base 5 Koke Base 6 Ilkay Gundogan Base 7 Marco Reus Base 8 Mats Hummels Base 9 Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang Base 10 Shinji Kagawa Base 11 Andres Iniesta Base 12 Dani Alves Base 13 Lionel Messi Base 14 Luis Suarez Base 15 Neymar Jr. Base 16 Arjen Robben Base 17 Arturo Vidal Base 18 Franck Ribery Base 19 Manuel Neuer Base 20 Thomas Muller Base 21 Fernando Muslera Base 22 Wesley Sneijder Base 23 David Luiz Base 24 Edinson Cavani Base 25 Marco Verratti Base 26 Thiago Silva Base 27 Zlatan Ibrahimovic Base 28 Cristiano Ronaldo Base 29 Gareth Bale Base 30 Keylor Navas Base 31 James Rodriguez Base 32 Raphael Varane Base 33 Karim Benzema Base 34 Axel Witsel Base 35 Ezequiel Garay Base 36 Hulk Base 37 Angel Di Maria Base 38 Gonzalo Higuain Base 39 Javier Mascherano Base 40 Lionel Messi Base 41 Pablo Zabaleta Base 42 Sergio Aguero Base 43 Eden Hazard Base 44 Jan Vertonghen Base 45 Marouane Fellaini Base 46 Romelu Lukaku Base 47 Thibaut Courtois Base 48 Vincent Kompany Base 49 Edin Dzeko Base 50 Dani Alves Base 51 David Luiz Base 52 Kaka Base 53 Neymar Jr. Base 54 Thiago Silva Base 55 Alexis Sanchez Base 56 Arturo Vidal Base 57 Claudio Bravo Base 58 James Rodriguez Base 59 Radamel Falcao Base 60 Ivan Rakitic Base 61 Luka Modric Base 62 Mario Mandzukic Base 63 Gary Cahill Base 64 Joe Hart Base 65 Raheem Sterling Base 66 Wayne Rooney Base 67 Hugo Lloris Base 68 Morgan Schneiderlin Base 69 Olivier Giroud Base 70 Patrice Evra Base 71 Paul -

Panini World Cup 2002 USA/European

www.soccercardindex.com Panini World Cup 2002 checklist □1 FIFA World Cup Trophy Costa Rica Nigeria Federation Logos □2 Official Emblem □44 Hernan Medford □82 JayJay Okocha □120 Argentina □3 Official Mascots □45 Paulo Wanchope □83 Sunday Oliseh □121 Belgium □84 Victor Agali □122 Brazil Official Posters Denmark □85 Nwankwo Kanu □123 China □4 1930 Uruguay □46 Thomas Helveg □124 Denmark □5 1934 Italia □47 Martin Laursen Paraguay □125 Germany □6 1938 France □48 Martin Jørgensen □86 Jose Luis Chilavert □126 France □7 1950 Brasil □49 Jon Dahl Tomasson □87 Carlos Gamarra □127 Croatia □8 1954 Helvetia □88 Roberto Miguel Acuna □128 Italy □9 1958 Sverige Germany □129 Japan □10 1962 Chile □50 Oliver Kahn Poland □130 Korea Republic □11 1966 England □51 Jens Nowotny □89 Tomasz Hajto □131 Mexico □12 1970 Mexico □52 Marko Rehmer □90 Emmanuel Olisadebe □132 Paraguay □13 1974 Deutschland BRD □53 Michael Ballack □133 Poland □14 1978 Argentina □54 Sebastian Deisler Portugal □134 Portugal □ □ □15 1982 Espana 55 Oliver Bierhoff 91 Sergio Conceicao □135 Saudi Arabia □ □ □16 1986 Mexico 56 Carsten Jancker 92 Luis Figo □136 South Africa □ □17 1990 Italia 93 Rui Costa □137 Sweden □ □18 1994 USA France 94 Nuno Gomes □138 Turkey □ □ □19 1998 France 57 Fabien Barthez 95 Pauleta □139 USA □ □20 2002 KoreaJapan 58 Vincent Candela □ Russia 59 Lilian Thuram □140 Checklist □ □96 Viktor Onopko Argentina 60 Patrick Vieira □ □21 Fabian Ayala □61 Zinedine Zidane 97 Alexander Mostovoi □ □22 Walter Samuel □62 Thierry Henry 98 Egor Titov □ □23 Kily Gonzalez □63 David Trezeguet -

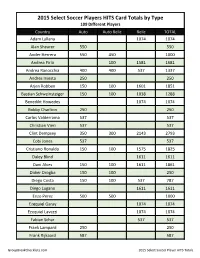

2015 Select Soccer Team HITS Checklist;

2015 Select Soccer Players HITS Card Totals by Type 109 Different Players Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Adam Lallana 1074 1074 Alan Shearer 550 550 Ander Herrera 550 450 1000 Andrea Pirlo 100 1581 1681 Andrea Ranocchia 400 400 537 1337 Andres Iniesta 250 250 Arjen Robben 150 100 1601 1851 Bastian Schweinsteiger 150 100 1038 1288 Benedikt Howedes 1074 1074 Bobby Charlton 250 250 Carlos Valderrama 537 537 Christian Vieri 537 537 Clint Dempsey 350 300 2143 2793 Cobi Jones 537 537 Cristiano Ronaldo 150 100 1575 1825 Daley Blind 1611 1611 Dani Alves 150 100 1611 1861 Didier Drogba 150 100 250 Diego Costa 150 100 537 787 Diego Lugano 1611 1611 Enzo Perez 500 500 1000 Ezequiel Garay 1074 1074 Ezequiel Lavezzi 1074 1074 Fabian Schar 537 537 Frank Lampard 250 250 Frank Rijkaard 587 587 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2015 Select Soccer Player HITS Totals Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Franz Beckenbauer 250 250 Gerard Pique 150 100 1601 1851 Gervinho 525 475 1611 2611 Gianluigi Buffon 125 125 1521 1771 Guillermo Ochoa 335 125 1611 2071 Harry Kane 513 503 537 1553 Hector Herrera 537 537 Hugo Sanchez 539 539 Iker Casillas 1591 1591 Ivan Rakitic 450 450 1024 1924 Ivan Zamorano 537 537 James Rodriguez 125 125 1611 1861 Jan Vertonghen 200 150 1074 1424 Jasper Cillessen 1575 1575 Javier Mascherano 1074 1074 Joao Moutinho 1611 1611 Joe Hart 175 175 1561 1911 John Terry 587 100 687 Jordan Henderson 1074 1074 Jorge Campos 587 587 Jozy Altidore 275 225 1611 2111 Juan Mata 425 375 800 Jurgen Klinsmann 250 250 Karim Benzema 537 537 Kevin Mirallas 525 475 -

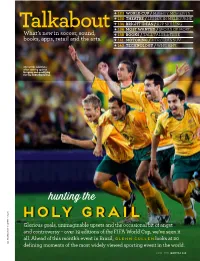

Australian Way June 2014

✈ 123 WORLD CUP / MIGHTY MOMENTS ✈ 130 THEATRE / LES MIS IN MELBOURNE ✈ 134 BRIGHT IDEAS / APP SKILLING Talkabout ✈ 136 MOST WANTED / SPOILS OF MORE What’s new in soccer, sound, ✈ 138 BOOKS / TALL TALES & TRUE books, apps, retail and the arts. ✈ 141 MOTORING / MERCEDES SUV ✈ 143 TECHNOLOGY / WI-FI HI-FI Socceroos celebrate after scoring against Uruguay and qualifying for the 2006 World Cup hunting the holyholy grailgrail Glorious goals, unimaginable upsets and the occasional bit of angst and controversy – over 19 editions of the FIFA World Cup, we’ve seen it all. Ahead of this month’s event in Brazil, GlenN Cullen looks at 20 ALL PHOTOGRAPHY: GETTY IMAGES defining moments of the most widely viewed sporting event in the world. JUNE 2014 QANTAS 123 Diego Maradona’s “Hand of God” goal The Lions of Cameroon, in 1986; Uruguay vs down to nine players, beat Argentina at the first defending champions World Cup (left) Argentina in 1990 #7 #9 1986 1990 #11 1994 Roberto Baggio (left) Diego Maradona misses a penalty and celebrates his second hands Brazil the 1994 goal against England in World Cup #1 1986 – this one scored 1930 with his boot 01 The game begins There were 93,000 people cheeky one-two with Giuseppe packed into Montevideo’s Giannini, Baggio slalomed through Estadio Centenario to see home the Czech defence, finally piercing side Uruguay get the ball rolling in two players and the keeper to the first World Cup final of 1930. score a silky goal. Much to the delight of the home nation, Uruguay beat Argentina 11 4-2 to clinch the title. -

Lionel Messi and the Art of Living

ANDY WEST LIONEL MESSI AND THE ART OF LIVING Contents Acknowledgements 7 Introduction 8 The Price of Success 15 Learning to Lose 45 The Brain Game 74 Strenuous Freedom 105 The Reciprocal Altruist 133 A Different River 161 A Better Life 190 Epilogue 219 Bibliography 222 Chapter One The Price of Success Argentina 2-1 Brazil FIFA World Youth Championship semi-final Tuesday 28 June 2005, Galgenwaard Stadion, Utrecht It is the summer of 2005, and the most talented young footballers on the planet have spent the last few weeks gathered in the Netherlands with dreams of winning the sport’s most prestigious junior tournament: the FIFA World Youth Championship After 36 games of intense competition, they have been whittled down to just four remaining teams – and one of the semi-finals is being contested between South American neighbours Argentina and Brazil, the protagonists of perhaps international football’s most famous and heated rivalry, whose brightest emerging stars are now going head to head for a place in the final With just six minutes played, the ball is passed to Argentina’s diminutive number 18, who receives possession slightly right of centre, around 30 yards from goal His name, the whole world will soon know, is Lionel Messi An attacking player for Spanish club FC Barcelona with a handful of first-team appearances already under his belt, Messi controls adroitly and looks up Seeing space to run into, he cuts inside and dribbles towards the penalty area, always keeping the ball on his favoured left foot Two, three, four little touches, -

La Historia Secreta

MARACANA La Historia Secreta "Vo... ¡No sean giles! Saquen acá que están los Campeones del Mundo" Atilio Garrido INDICE Pág. - Presentación ¡ .... 5 PRIMERA PARTE: Los prolegómenos Capítulo 11 La huelga y el Sudamericano - El gobierno de la AUF en manos de la Junta Dirigente 15 - Reglamento de ia Copa de .1950 y Sudamericano de 1949 17 - La huelga de los jugadores uruguayos 17 - Enrique Castro, Presidente de la MUTUAL, fue el líder 19 - Exclusivos testimonios del Dr. Reyes Rius 20 - Un minuto de paro en el Estadio Centenario ..21 - Los Batlle, Perón y la huelga rioplatense 22 - Huelga en Argentina; contacto rioplatense entre dirigentes 23 - La huelga en la agenda política del ÜrugUay 23 - La huelga contó con la simpatía popuiar 24 - Brasil posterga el Sudamericano para esperar a Ürügiiay 25 - ¿Nacional perjudicado por la huelga? 27 - La MÜTÜAL cede; ia AÜF actúa con decisión .28 - Racing de gira; Aníbal Paz expulsado de la MÜTÜAL... .....29 - Peñaroi, muy activo, propone ia "Bolsa de Jugadores" 30 - Enrique Castro y el aviso a los navegantes ¡ 32 - Peñaroi gana Una batalla en la Junta: Uruguay al Sudamericano 32 - La reacción de la MUTUAL y la carta de Enrique Castro...................: 33 - Matías González: "Cumplir con un deber, defender la celeste" 34 - La MÜTÜAL expulsa a los 4 "rompe huelgas" 35 - Los "rompe huelga"ante el ¿poderoso? Brasil „... 36 - Los "rompe huelga" adelantaron el "Maracahazo" 38 - ¡Los suplentes "rompe huelga" derrotan a Botafogo! 39 - "Sáojanúariazo" de Paraguay adelanta el "Maracanazó" 40 - El camino final de la huelga 41 - El documento aprobado por la AUF y "los jugadores". -

Advertencia Violeta Por Las Bajas Temperaturas

K Y M C Distribución en La Plata, Berisso y Ensenada. Aprendía a conducir Precio de tapa: $50 Entrega bajo puerta: $50 y chocó contra un micro en Ensenada Año XXVII • Nº 8896 La Plata, miércoles 28 de julio de 2021 Edición de 32 páginas En la noticia -PÁG 15 TRAMA URBANA ELECCIONES LEGISLATIVAS Vacunarán a las autoridades de mesa Los ciudadanos designados como autoridades de mesa para las Buenos Aires próximas elecciones serán vacunados contra la Covid-19, anunció el Ministerio del Interior a la Cámara Nacional Electoral muy cerca del -PÁG. 2 Económicas reabrirá sus puertas En la Provincia la fase 2 es un mal recuerdo y desde el lunes habrá presencialidad en los La reapertura será por etapas y de manera gradual. Del 2 al 7 de colegiosefecto de los 135 municipios. Axel Kicillof rebañoanunció la vacunación libre para los mayores agosto los estudiantes tendrán la de 25 años a partir de hoy y desde el viernes para los mayores de 18. También se abrió la posibilidad de rendir los exámenes finales de forma presencial inscripción para los mayores de 12. El Gobierno nacional logró un acuerdo con Pfizer para -PÁG. 9 comprar 20 millones de vacunas y en agosto priorizará la aplicación de segundas dosis Moderna y Pfizer -PÁGS. 3 A 5 prueban vacunas en niños de 5 a 11 años La Administración de Alimentos y Fármacos de Estados Unidos solicitó que amplíen el número de voluntarios para detectar efectos secundarios poco comunes Advertencia -PÁG. 10 Entrevista exclusiva violeta por a Edgar Ramírez las bajas temperaturasLa medida fue emitida por el Servicio Meteorológico Nacional y abarca a gran parte del país. -

Redalyc.Da Expectativa Fremente À Decepção Amarga

Revista de História ISSN: 0034-8309 [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo Brasil Franzini, Fábio Da expectativa fremente à decepção amarga: o Brasil e a Copa do Mundo de 1950 Revista de História, núm. 163, julio-diciembre, 2010, pp. 243-274 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=285022061012 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto Fábio FRANZINI. Da expectativa fremente à decepção amarga DA EXPECTATIVA FREMENTE À DECEPÇÃO AMARGA: O BRASIL E A COpa DO MUNDO DE 1950* Fábio Franzini Doutor em História Social pela Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo e professor do curso de História da Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de São Paulo Resumo Este artigo apresenta e discute um momento crucial da história do futebol brasileiro: a Copa do Mundo de 1950. Da escolha do Brasil como sede da competição à derrota da seleção nacional para o Uruguai no Maracanã, a análise pretende demonstrar como o país então se envolveu profundamente com o futebol e projetou a sua própria consagração no sucesso da equipe, consagração essa frustrada pela perda do título mundial. Palavras-chave Copa do Mundo • futebol e sociedade • futebol e nacionalismo. Correspondência Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de São Paulo Estrada do Caminho Velho, 333 07252-312 – Bairro dos Pimentas – Guarulhos – SP.