Kelly Oliver 1 Reading Nietzsche With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Essay in Honour of Mary-Anne Elizabeth Plaatjies-Van Huffel

Article Recognition Discourse and Systemic Gender Injustice: An Essay in Honour of Mary-Anne Elizabeth Plaatjies-Van Huffel Robert Vosloo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7144-9644 Stellenbosch University [email protected] Abstract Against the backdrop of the South African Reformed ecclesiologist Mary-Anne Elizabeth Plaatjies-Van Huffel’s reflections on gender insensitivity in church and society, this article engages with the notion of recognition, a concept that has found strong currency in many contemporary discourses. The first part of the article mentions the promise of recognition as a moral, political, and also theological category. In addition, it also interrogates the term in conversation with theorists who raise some critical concerns regarding accounts of recognition that are not adequately justice-sensitive. The second part of the article enters more directly into conversation with some of the writings of Plaatjies-Van Huffel, highlighting in the process her emphasis that the recognition of women should not be dislocated from a plea for a change in the dynamics of patriarchal power and structural gender injustice. The article concludes with a call to move beyond what is termed “cheap recognition.” Keywords: Mary-Anne Elizabeth Plaatjies-Van Huffel; recognition; justice; gender insensitivity; patriarchal power Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/8250 https://upjournals.co.za/index.php/SHE/index ISSN 2412-4265(Online)ISSN 1017-0499(Print) Volume 47 | Number 2 | 2021 | #8250 | 13 pages © The Author(s) -

Copyright by Berna Gueneli 2011

Copyright by Berna Gueneli 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Berna Gueneli Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CHALLENGING EUROPEAN BORDERS: FATIH AKIN’S FILMIC VISIONS OF EUROPE Committee: Sabine Hake, Supervisor Katherine Arens Philip Broadbent Hans-Bernhard Moeller Pascale Bos Jennifer Fuller CHALLENGING EUROPEAN BORDERS: FATIH AKIN’S FILMIC VISIONS OF EUROPE by Berna Gueneli, B.A., M.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication For my parents Mustafa and Günay Güneli and my siblings Ali and Nur. Acknowledgements Scholarly work in general and the writing of a dissertation in particular can be an extremely solitary endeavor, yet, this dissertation could not have been written without the endless support of the many wonderful people I was fortunate to have in my surroundings. First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation advisor Sabine Hake. This project could not have been realized without the wisdom, patience, support, and encouragement I received from her, or without the intellectual exchanges we have had throughout my graduate student life in general and during the dissertation writing process in particular. Furthermore, I would like to thank Philip Broadbent for discussing ideas for this project with me. I am grateful to him and to all my committee members for their thorough comments and helpful feedback. I would also like to extend my thanks to my many academic mentors here at the University of Texas who have continuously guided me throughout my intellectual journey in graduate school through inspiring scholarly questions, discussing ideas, and encouraging my intellectual quest within the field of Germanic and Media Studies. -

Sexual Difference, Animal Difference: Derrida and Difference

H Y P A 1032 Dispatch: 18.2.09 Journal: HYPA CE: Nikhil Journal Name Manuscript No. B Author Received: No. of pages: 23 Op: Sumesh 1 Sexual Difference, Animal Difference: 2 3 Derrida and Difference ‘‘Worthy of its 4 5 Name’’ 6 7 8 KELLY OLIVER 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 I challenge the age-old binary opposition between human and animal, not as philos- 16 ophers sometimes do by claiming that humans are also animals, or that animals are 17 capable of suffering or intelligence, but rather by questioning the very category of ‘‘the 18 animal’’ itself. This category groups a nearly infinite variety of living beings into one 19 concept measured in terms of humans—animals are those creatures that are not 20 human. In addition, I argue that the binary opposition between human and animal is 21 intimately linked to the binary opposition between man and woman. Furthermore, I 22 suggest that thinking through animal differences or differences among various living 23 creatures opens up the possibility of thinking beyond the dualist notion of sexual 24 difference and enables thinking toward a multiplicity of sexual differences. 25 26 27 28 Reading the history of philosophy, feminists have pointed out that ‘‘female,’’ 29 ‘‘woman,’’ and ‘‘femininity’’ often fall on the side of the animal in the human– 30 animal divide, as the frequent generic use of the word ‘‘man’’ suggests. From 31 Plato through Hegel, Freud and beyond, women have been associated with 32 Nature and instincts to procreate, which place them in the vicinity of the an- 33 imal realm. -

Real Fit: Identity, Society, and Viewer Investment in Fitness Reality TV

Real Fit: Identity, Society, and Viewer Investment in Fitness Reality TV By Juliana Lewis Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Philosophy May 2015 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Kelly Oliver, Ph.D. José Medina, Ph.D. Lisa Guenther, Ph.D. Ellen Armour, Ph.D. Dedicated to my parents for their encouragement and support. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to my dissertation chair Kelly Oliver for expanding my philosophical world to explorations of visual media and psychoanalytic theory, and for her guidance; this work would not have been possible without her mentorship and support. Thanks also to my committee members, José Medina, Lisa Guenther, and Ellen Armour for their time and feedback. I am grateful to my friends and colleagues Rebecca Tuvel, Alison Suen, and Elizabeth Edenberg for keeping me connected to the Philosophy Department while working at a great distance. Finally, I am thankful for the Vanderbilt Philosophy Department’s support. iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1—Protester outside the White House protesting Ebola Response (Messing 2014)....................................................22 2—Dolvett talks to his team (DeGroot 2014b, 16:10) .................................................................................................35 3—Jessie and Laurie's Conversation (DeGroot 2014a, 28:40).....................................................................................37 4—Jennifer and -

The Censored Paintings of Paul Cadmus, 1934-1940

THE CENSORED PAINTINGS OF PAUL CADMUS, 1934-1940: THE BODY AS THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE DECENT AND OBSCENE by ANTHONY J. MORRIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Anthony J. Morris, candidate for the PhD degree*. ________________ Henry Adams ________________ (chair of the committee) ________________ Ellen G. Landau ______________ ________________ T. Kenny Fountain ____________ ________________ Renée Sentilles _______________ Date: March 15, 2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Table of Contents: Table of Contents: ii. List of Figures v. Acknowledgements xi. Abstract xiii. Chapter I Introduction: Censorship and the American Scene 1. Censorship of Sex: The Comstock Laws 3. Censorship of Hate Speech: Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” 10. Censorship of Political Ideology: Diego Rivera 13. Censorship and the New Deal Mural Program 16. Paul Cadmus and Other Painters of the American Scene 21. The Depiction of the Working Class 23. The Depiction of Women and Sexuality 27. The Depiction of Alcohol Following the Prohibition Era 31. Chapter II Historiography of Paul Cadmus: The Gay Satirist 34. 1930s: Repulsive Subjects and Garish Color 35. 1941-1968: Near Silence 41. 1968-1992: Re-emergence and Re-considered 44. 1992-present: Queering Paul Cadmus 51. ii Chapter III The Navy, The New Deal, and The Fleet’s In! Reconsidered 59. The National Exhibition of Art by the Public Works of Art Project 60. -

![Bearing Witness: Hope for the Unseen [Post-Print]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5036/bearing-witness-hope-for-the-unseen-post-print-4275036.webp)

Bearing Witness: Hope for the Unseen [Post-Print]

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Faculty Scholarship 3-2016 Bearing Witness: Hope for the Unseen [post-print] Tamsin Jones Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/facpub Part of the Religion Commons Bearing Witness: Hope for the Unseen Accepted Manuscript for Political Theology 17.2 (2016): 137-150 Tamsin Jones For ere this the tribes of men lived on earth remote and free from ills and hard toil and heavy sickness which bring the Fates upon men; for in misery men grow old quickly. But the woman took off the great lid of the jar with her hands and scattered all these and her thought caused sorrow and mischief to men. Only Hope remained there in an unbreakable home within under the rim of the great jar, and did not fly out at the door… (Hesiod, Works and Days II: 90-100).1 To try to make sense of one’s life is to gather one’s own and the community’s memories in an attempt to produce some kind of fit, some kind of mutual accommodation. But this project is continually undone by the world, by deep, open attention to the world.2 In Hesiod’s myth of Pandora, after she unwittingly unleashes a world of evil and suffering upon man (whom she was sent to companion3), one gift remains captive within the jar—ἐλπίς, or hope. At first glance, this would seem to be humanity’s saving grace. However, within the commentary on Hesiod, there is some disagreement regarding just how we are to interpret this remaining gift. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE CHAD KAUTZER Philosophy Department 161 Lafayette Avenue 15 University Drive Apt. 3A Lehigh University Brooklyn, NY 11238 Bethlehem, PA 18015 720-288-5236 EDUCATION 2008 Ph.D., Stony Brook University, Philosophy 2006-2007 Transatlantic Collegium of Philosophy Fellow, Johann Wolfgang Goethe- Universität, Frankfurt, Germany 2004-2005 German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) Fellow, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt, Germany 1998 B.A., University of Wisconsin-Madison, Philosophy & German PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2016 - Associate Professor, Philosophy Department, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania 2015 - 2016 Visiting Research Scholar, Philosophy Department, Graduate Center of the City University of New York 2015 - 2016 Associate Professor, Philosophy Department, University of Colorado Denver 2008 - 2015 Assistant Professor, Philosophy Department, University of Colorado Denver 2011 - 2012 Adjunct Professor, Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Colorado Boulder 2002 - 2007 Lecturer, Philosophy Department, Stony Brook University PUBLICATIONS Books 2015 Radical Philosophy: An Introduction (Routledge, 2015). 2009 Pragmatism, Nation, and Race: Community in the Age of Empire (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press), co-edited with Eduardo Mendieta. Contributors include Mitchel Aboulafia, James Bohman, Robert Brandom, David Kim, Eduardo Mendieta, Lucius T. Outlaw, Jr., Max Pensky, Richard Rorty, Tommie Shelby, Shannon Sullivan, Robert Westbrook, and Cynthia Willet. 1 In Preparation Good Guys with Guns: Whiteness, Masculinity, and the New Politics of Sovereignty. A study of the emergence of a new form of political subjectivity in American gun culture. In Preparation Hegel and the Colonial World: From European Freedom to Decolonial Resistance. A study of the role of European colonialism in Hegel’s philosophy of history and right as well as Hegel’s influence on twentieth-century decolonial theory. -

Witnessing and Testimony

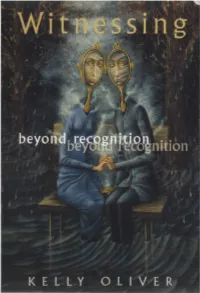

parallax, 2004, vol. 10, no. 1, 79–88 Witnessing and Testimony Kelly Oliver Contemporary debates in social theory around issues of multiculturalism have focused on the demand or struggle for recognition by marginalized or oppressed people, groups, and cultures. The work of Charles Taylor and Axel Honneth, in particular, have crystallized issues of multiculturalism and justice around the notion of recognition.1 In Witnessing: Beyond Recognition, I challenge what has become a fundamental tenet of this trend in debates over multiculturalism, namely, that the social struggles manifest in critical race theory, queer theory, feminist theory, and various social movements are struggles for recognition.2 Testimonies from the aftermath of the Holocaust and slavery do not merely articulate a demand to be recognized or to be seen. Rather, they witness to pathos beyond recognition. The victims of oppression, slavery, and torture are not merely seeking visibility and recognition, but they are also seeking witnesses to horrors beyond recognition. The demand for recognition manifest in testimonies from those othered by dominant culture is transformed by the accompanying demands for retribution and compassion. If, as I suggest, those othered by dominant culture are seeking not only, or even primarily, recognition but also witnessing to something beyond recognition, then our notions of recognition must be reevaluated. Certainly notions of recognition that throw us back into a Hegelian master-slave relationship do not help us to overcome domination. If recognition is conceived as being conferred on others by the dominant group, then it merely repeats the dynamic of hierarchies, privilege, and domination. Even if oppressed people are making demands for recognition, insofar as those who are dominant are empowered to confer it, we are thrown back into the hierarchy of domination. -

Earth and World

3 PLURALITY AS THE LAW OF THE EARTH Arendt Human beings in the true sense of the term can exist only where there is a world, and there can be a world in the true sense of the term only where the plurality of the human race is more than a simple multiplication of a single species. —HANNAH ARENDT, THE PROMISE OF POLITICS ike Kant’s doctrine of right, which is circumscribed by the spherical shape of the earth, Arendt’s notion of politics is similarly based on “the limited space for the Lmovement of men” determined by the surface of the earth (Arendt 1958a, 52). As we have seen in our analysis of Kant, however, the earth remains in excess of Kant’s doctrine of right insofar as it is based on private property. The earth cannot be contained within his theory of property. Indeed, the earth with all of its inhabitants exceeds his notion of the right to hospitality and his limited cosmopolitanism as guarantees for peace, or, more accurately, we might say Kant’s extraterrestrial relation to the earth makes his cosmopolitanism itself exceed the boundaries that he tries to set for it insofar as ultimately it requires that all rational beings, be they human or not, earthlings or not, throughout all of time and all of space, be united in a general will. Whereas Kant imagines a distant future in which the human species will have evolved into a peaceful race of citizens of the world, Arendt, respects the need for international law, even while she abhors cosmopolitanism, which she imagines as a nightmarish tyranny of one government over the “whole earth” (Arendt 1968a, 81). -

A874963d7f37b8a0a74d1d4a08

Witnessing Beyond Recognition KELLY OLIVER University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis E ;so London a A version of part of chapter 1 was published as "Beyond Recognition: Witnessing Ethics," Philosophy Today44, no. 1 (spring 2000); copyright 2000 DePaul University, reprinted here with permission fromDePaul University. A version of part of chap ter 3 was published as "What Is Transformative about the Performative? From Repeti tion to Working Through," Studies in Practical Philosophy 1, no. 2 (falll999); copy right Humanities Press, Inc., reprinted with permission from Humanities Press, Inc. Copyright 2001 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any fo rm or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press Ill Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 5540 1-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Oliver, Kelly, 1958- Witnessing : beyond recognition I Kelly Oliver. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8166-3627-3 (alk. paper) - ISBN 0-8166-3628-1 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Recognition (Philosophy) 2. Perception (Philosophy) 3. Social perception. I. Title. B828.45 .055 2001 128-dc21 00-009646 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. 11 10 09 08 07 06 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 ForRuthy who has survived unimaginable torture, and who, in the last year, has taught me more about the anxieties, response-abilities, joys, courage, vigilance, and necessity of loving than books ever could. -

Kelly Oliver Technologies of Life and Death: from Cloning to Capital Punishment New York: Fordham University Press, 2013 ISBN: 978-0-8232-5109-4 (PB) £16.99

Kelly Oliver Technologies of Life and Death: From Cloning to Capital Punishment New York: Fordham University Press, 2013 ISBN: 978-0-8232-5109-4 (PB) £16.99. 272 pp. Bioethicists have long acknowledged that new technologies bring new ethical dilemmas. The notion behind this truism is that the novelty of situations created by technology both tests our applications of, and calls into question, prior concepts such as when life begins and when death occurs. Life support technologies required us to consider whether life ended only when the heart stopped beating, or perhaps at brain death, since the two could be commonly separated for the first time in human history; new imaging and monitoring technologies allowed us to see inside a pregnant woman’s womb during gestation, to detect limb growth, heartbeat, pain response and so forth. Such conceptual inquiry is a key feature of modern bioethics. Oliver is engaged in a similar questioning of fundamental concepts. She identifies pairs of concepts often seen as markedly distinct from one another, binaries which she rightly argues underdetermine our judgments on nearly all these ‘technologies of life and death’. The technologies Oliver addresses include genetic engineering, artificial insemination and surrogacy (technologies of life) as well as autopsy and capital punishment (technologies of death). Along the way, she considers the use and abuse of non-human animals as part and parcel of our attitude toward technology and knowledge. The binaries she identifies include nature vs. culture, grown vs. made, chance vs. choice/control, accident vs. deliberation, nature vs. culture and human vs. animal. Throughout the book, she addresses all of these, and shows how they shape our thinking again and again on issue after issue in surprising ways. -

Earth and World: Philosophy After the Apollo Missions

5 THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH Derrida lthough the earth does not occupy a central place in Jacques Derrida’s writings, his last seminar is all about the world. More exactly, it is about the Adestruction of the world that results from the death of each singular living being and the disappearance of the world necessary for ethics. Derrida begins his exploration of the receding world by following in the footsteps of Robinson Crusoe as he retraces them over and again on the desert island. Derrida takes up the question of what is an island, and his analysis of Robinson Crusoe revolves around the ways in which the island both is and is not deserted, as well as Robinson Crusoe’s ambivalent relation to the island, his attraction and repulsion. Although Derrida is not thinking of “this island earth,” imagining the Earth as an island, isolated and alone, floating against the vast sea of space, as the astronauts did, conjures the ambivalent reactions he attributes to all islands. In The Beast and the Sovereign Volume II, Derrida asks, “Why does one love islands? Why does one not love islands? Why do some people love islands while others do not love islands, some people dreaming of them, seeking them out, inhabiting them, taking refuge on them, and others avoiding them, even fleeing them instead of taking refuge on them?” (Derrida 2011, 64). He continues this line of question, asking what is it that one flees or seeks when one escapes from, or takes refuge on, an island. He proposes that we find these seemingly contradictory desires in the same person, even in “the same desire” (69).