Female Sexuality and Maternal Archetypes in Kate Chopin's The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Krt Madonna Knight Ridder/Tribune

FOLIO LINE FOLIO LINE FOLIO LINE “Music” “Ray of Light” “Something to Remember” “Bedtime Stories” “Erotica” “The Immaculate “I’m Breathless” “Like a Prayer” “You Can Dance” (2000; Maverick) (1998; Maverick) (1995; Maverick) (1994; Maverick) (1992; Maverick) Collection”(1990; Sire) (1990; Sire) (1989; Sire) (1987; Sire) BY CHUCK MYERS Knight Ridder/Tribune Information Services hether a virgin, vamp or techno wrangler, Madon- na has mastered the public- image makeover. With a keen sense of what will sell, she reinvents herself Who’s That Girl? and transforms her music in Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone was ways that mystify critics and generate fan interest. born on Aug. 16, 1958, in Bay City, Mich. Madonna staked her claim to the public eye by challenging social norms. Her public persona has Oh Father evolved over the years, from campy vixen to full- Madonna’s father, Sylvio, was a design en- figured screen siren to platinum bombshell to gineer for Chrysler/General Dynamics. Her leather-clad femme fatale. Crucifixes, outerwear mother, Madonna, died of breast cancer in undies and erotic fetishes punctuated her act and 1963. Her father later married Joan Gustafson, riled critics. a woman who had worked as the Ciccone Part of Madonna’s secret to success has been family housekeeper. her ability to ride the music video train to stardom. The onetime self-professed “Boy Toy” burst onto I’ve Learned My Lesson Well the pop music scene with a string of successful Madonna was an honor roll student at music video hits on MTV during the 1980s. With Adams High School in Rochester, Mich. -

The U2 360- Degree Tour and Its Implications on the Concert Industry

THE BIGGEST SHOW ON EARTH: The U2 360- Degree Tour and its implications on the Concert Industry An Undergraduate Honors Thesis by Daniel Dicker Senior V449 Professor Monika Herzig April 2011 Abstract The rock band U2 is currently touring stadiums and arenas across the globe in what is, by all accounts, the most ambitious and expensive concert tour and stage design in the history of the live music business. U2’s 360-Degree Tour, produced and marketed by Live Nation Entertainment, is projected to become the top-grossing tour of all time when it concludes in July of 2011. This is due to a number of different factors that this thesis will examine: the stature of the band, the stature of the ticket-seller and concert-producer, the ambitious and attendance- boosting design of the stage, the relatively-low ticket price when compared with the ticket prices of other tours and the scope of the concert's production, and the resiliency of ticket sales despite a poor economy. After investigating these aspects of the tour, this thesis will determine that this concert endeavor will become a new model for arena level touring and analyze the factors for success. Introduction The concert industry handbook is being rewritten by U2 - a band that has released blockbuster albums and embarked on sell-out concert tours for over three decades - and the largest concert promotion company in the world, Live Nation. This thesis is an examination of how these and other forces have aligned to produce and execute the most impressive concert production and single-most successful concert tour in history. -

Welcome Booklet Orientation International Students

Welcome Booklet Orientation International Students Congratulations on your acceptance to Madonna University! On the next page is a checklist for you to follow to make arrangements for your travel to the United States and to Madonna University. On the pages after the checklist is detailed information related to each activity. Refer to the entire Welcome Booklet for the information you will need. Domestic International Booklet September, 2016 Page 1 Domestic International Booklet September, 2016 Page 1 Checklist Make sure you RSVP as soon as possible! Go to the following link to complete the Arrival Form: https://ww4.madonna.edu/mucfweb/ssl_forms/International_Arrival/client/general_for m_2.cfm SUBMIT ENROLLMENT DEPOSIT OF $50.00 REGISTER FOR ENGLISH (ESL) PLACEMENT TEST (Deadline for Fall, 2017: May 1, 2017) (IF APPLICABLE) (See instruction on online payment process on To register for ESL placement test, complete Page 3.) Arrival RSVP form. ESL Program Information: SEND OFFICIAL FINAL TRANSCIPT https://www.madonna.edu/academics/esl REQUEST SEVIS DATA RELEASE FROM YOUR CURRENT Or E-mail: Ms. Hadeel Betti for more information: [email protected] SCHOOL TO MADONNA UNIVERSITY Students who have met the English Proficiency REPORT TO INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS OFFICE WITHIN Requirement will be required to take a writing 15 DAYS OF YOUR PROGRAM START DATE assessment test during the first semester of study. RSVP FOR ATTENDING INTERNATIONAL STUDENT APPLY FOR ON-CAMPUS HOUSING ORIENTATION Submit Residence Hall Contract and $175.00 deposit to: Use the RSVP link above Madonna University Email Ms. Amy Dickerson for more information: Student Accounts Office [email protected] 36600 Schoolcraft Road ACTIVATE E-MAIL AND ACESS MY PORTAL Livonia, Michigan 48150, USA Contact [email protected] or 734-432- Attn: Ms. -

Ciaran Gribbin

Ciaran Gribbin Ciaran Gribbin is a Grammy nominated songwriter and performer who, in addition to working with word class artists such as Madonna, U2, Paul McCartney, Snow Patrol and Al Pacino, has toured the world as the singer of INXS. Ciaran was born in war-torn Northern Ireland growing up in ‘The Troubles’. As a young musician he cut his teeth doing gig after gig in the tough bars of Belfast and Derry. During this turbulent time in a divided society, Ciaran witnessed and experienced the bombs and bullets of sectarian abuse and paramilitary attacks. Ciaran’s first big break came in 2010 when he received a Grammy nomination for Madonna’s worldwide hit single ‘Celebration’, which he co-wrote with Madonna and Oakenfold. Since then, in addition to performing at many music festivals including Brazil’s ‘Rock in Rio’, Ciaran has opened shows for Paul McCartney, Crowded House, The Script and Gotye. Ciaran has worked extensively as a songwriter for acts such as Groove Armada and Dead Mau5. He has also worked on multiple movie soundtracks including writing all of the original songs for the U2 supported movie ‘Killing Bono’. This movie was released through Paramount Pictures with a Sony Music soundtrack album. In 2011 Ciaran became the singer of the legendary Australian band INXS. He has toured extensively with INXS throughout South America, Europe and Australasia. 2015 ended with an Oscar shortlist nomination for Ciaran’s song 'Hey Baby Doll' which was sung by Al Pacino in the critically acclaimed movie 'Danny Collins'. “Ciaran has one of the most Ciaran is the founder of Rock and Roll Team Building and extraordinary voices I’ve heard in along with original INXS member, Garry Beers, is a founding member of the super-group ‘Stadium’ who are based in Los a long time.” Angeles. -

The Madonna Angel Wings Program

Who is Your Angel? Recent grateful patients shared the My gift of $_____ is given in honor of: following comments about their A grateful patient, family and friends program Madonna Angels: at Madonna Rehabilitation Hospitals Please fill-in one: ☐ Employee to be honored: ______________________ “Brent made sure I got off the ventilator and kept ☐ Department to be honored: _____________________ my voice. He was tough but encouraging. He gave HONOR A me hope.” SPECIAL Comments: (Enclose an extra page if needed.) CAREGIVER! ___________________________________________ “Chandra really made a ___________________________________________ difference in my recovery. Madonna is very lucky to ___________________________________________ have such a valuable staff ___________________________________________ member. I knew that when Chandra got me up and going in the morning, I would have a good day.” My Name: ___________________________________ “Thank you to Janelle for keeping me motivated and Address: ____________________________________ showing me that it takes time and effort. I appreciate all you have done for me.” City/State/Zip: _________________________________ Daytime Phone Number: (___)_____________________ “Everyone that took care of me was really great but Lincoln, NE 68506 5401 South Street E-mail address: ________________________________ Lori helped me a lot and was fun to work with — she is a great lady. Madonna is such a great hospital; I almost didn’t want to go home!” ☐ My gift is enclosed “Let me assure you that John sets the standard (Please make check payable to the Madonna Foundation) for what I believe should be the expectation for a rehabilitation hospital with the stature of Madonna.” ☐ Please charge my credit card: ☐ Visa ☐ MasterCard ☐ American Express ☐ Discover “Rhonda was fun and had you doing things you didn’t think you could. -

PLAYNOTES Season: 43 Issue: 05

PLAYNOTES SEASON: 43 ISSUE: 05 BACKGROUND INFORMATION PORTLANDSTAGE The Theater of Maine INTERVIEWS & COMMENTARY AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY Discussion Series The Artistic Perspective, hosted by Artistic Director Anita Stewart, is an opportunity for audience members to delve deeper into the themes of the show through conversation with special guests. A different scholar, visiting artist, playwright, or other expert will join the discussion each time. The Artistic Perspective discussions are held after the first Sunday matinee performance. Page to Stage discussions are presented in partnership with the Portland Public Library. These discussions, led by Portland Stage artistic staff, actors, directors, and designers answer questions, share stories and explore the challenges of bringing a particular play to the stage. Page to Stage occurs at noon on the Tuesday after a show opens at the Portland Public Library’s Main Branch. Feel free to bring your lunch! Curtain Call discussions offer a rare opportunity for audience members to talk about the production with the performers. Through this forum, the audience and cast explore topics that range from the process of rehearsing and producing the text to character development to issues raised by the work Curtain Call discussions are held after the second Sunday matinee performance. All discussions are free and open to the public. Show attendance is not required. To subscribe to a discussion series performance, please call the Box Office at 207.774.0465. By Johnathan Tollins Portland Stage Company Educational Programs are generously supported through the annual donations of hundreds of individuals and businesses, as well as special funding from: The Davis Family Foundation Funded in part by a grant from our Educational Partner, the Maine Arts Commission, an independent state agency supported by the National Endowment for the Arts. -

Madonna Rain Song Free Download

Madonna rain song free download click here to download Watch the video, get the download or listen to Madonna – Rain for free. Rain appears on the album Something to Remember. Discover more music, gig and. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Madonna – Rain for free. Erotica is related to sex so yes this song is about female orgasm and ejaculation. Madonna - Rain mp3 free download for mobile. Title: Rain (Album Version) | Preview · Download original Kbps, Mb, Album: Something To. Madonna Rain () - file type: mp3 - download - bitrate: kbps. Buy Rain: Read 6 Digital Music Reviews - www.doorway.ru Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of millions more Madonna WMG Rain. Madonna my sister died at the age of 33 of cancer this song played on the radio on my. Madonna - Rain - Official Video - "Suscribite" fabius tube1 year ago. i love how she. Madonna download music free true blue, how high. Madonna secret instrumental, rain radio mix die another day deepsky remix. Madonna single collection cd. Madonna - Rain (), wonderful song from the album "Erotica". Quite different I also loved this bootleg of yours, but the download button is not working.:/. This browser doesn't support Spotify Web Player. Switch browsers or download Spotify for your desktop. Rain. By Madonna. • 1 song, Play on Spotify. Download song Madonna - Rain in mp3 or listen free music online www.doorway.ru PM - 31 May 0 replies 0 retweets 0. Rain Official Song Download Free Mp3 Download in high quality bit. Play & Download Size MB ~ ~ kbps Free Madonna www.doorway.ru3. -

Deconstructing the Madonna/Whore Dichotomy in the Scarlet Letter, the Awakening, and the Virgin Suicides Whitney Greer University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2016 The aM donna, The Whore, The yM th: Deconstructing the Madonna/Whore Dichotomy in the Scarlet Letter, the Awakening, and the Virgin Suicides Whitney Greer University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greer, Whitney, "The aM donna, The Whore, The yM th: Deconstructing the Madonna/Whore Dichotomy in the Scarlet Letter, the Awakening, and the Virgin Suicides" (2016). Honors Theses. 943. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/943 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MADONNA, THE WHORE, THE MYTH: DECONSTRUCTING THE MADONNA/WHORE DICHOTOMY IN THE SCARLET LETTER, THE AWAKENING, AND THE VIRGIN SUICIDES By Whitney Greer A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Oxford May 2016 Approved by: _________________________________ Advisor Dr. Theresa Starkey _________________________________ Reader Dr. Jaime Harker _________________________________ Reader Dr. Debra Young © 2016 Whitney Elizabeth Greer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my family for supporting me, I could not have done this without you. Thank you to my grandfather, Charles, for your unfaltering love and support—you have made the world available to me. -

Why I Too Write About Beyoncé

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Why I Too Write About Beyoncé Kooijman, J. DOI 10.1080/19392397.2019.1630158 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in Celebrity Studies License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kooijman, J. (2019). Why I Too Write About Beyoncé. Celebrity Studies, 10(3), 432-435. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2019.1630158 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 CELEBRITY STUDIES 2019, VOL. 10, NO. 3, 432–435 https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2019.1630158 FORUM Why I too write about Beyoncé Jaap Kooijman Media Studies, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands ARTICLE HISTORY Received 1 December 2016; Accepted 1 April 2017 One day after Beyoncé Knowles released her 2016 album Lemonade, Damon Young pub- lished an open letter to ‘white people who write things’, giving them (including me) the following advice: either don’t comment on the album or wait until ‘you’ve read dozens of the smartest and sharpest assessments and deconstructions of Lemonade written by Black people’ (Young 2016). -

Chapter Outline

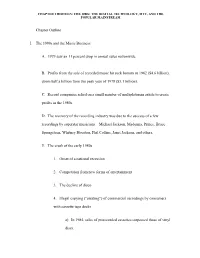

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THE 1980s: THE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, MTV, AND THE POPULAR MAINSTREAM Chapter Outline I. The 1980s and the Music Business A. 1979 saw an 11 percent drop in annual sales nationwide. B. Profits from the sale of recorded music hit rock bottom in 1982 ($4.6 billion), down half a billion from the peak year of 1978 ($5.1 billion). C. Record companies relied on a small number of multiplatinum artists to create profits in the 1980s. D. The recovery of the recording industry was due to the success of a few recordings by superstar musicians—Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince, Bruce Springsteen, Whitney Houston, Phil Collins, Janet Jackson, and others. E. The crash of the early 1980s 1. Onset of a national recession 2. Competition from new forms of entertainment 3. The decline of disco 4. Illegal copying (“pirating”) of commercial recordings by consumers with cassette tape decks a) In 1984, sales of prerecorded cassettes surpassed those of vinyl discs. CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THE 1980s: THE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, MTV, AND THE POPULAR MAINSTREAM F. New technologies of the 1980s 1. Digital sound recording and five-inch compact discs (CDs) 2. The first CDs went on sale in 1983, and by 1988, sales of CDs surpassed those of vinyl discs. 3. New devices for producing and manipulating sound: a) Drum machines b) Sequencers c) Samplers d) MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) G. Music Television (MTV) 1. Began broadcasting in 1981 2. Changed the way the music industry operated, rapidly becoming the preferred method for launching a new act or promoting a superstar’s latest release. -

Mary, Our Model and Patron

BLESSED ADELE DE BATZ – FOUNDER OF THE DAUGHTERS OF MARY IMMACULATE (MARIANISTS) MARY, OUR MODEL AND PATRON MAY 2018 IN ADELE’S WORDS — Nº 4 Sr. Caty Pilenga, FMI Community of Monteortone (Italy) “Always take as your model, the Most Holy Virgin, our good Patron ” (229.4) From her early childhood, Adele lived and breathed her family’s Christian atmosphere, which led her to love Jesus, to confide in the Virgin Mary and to pay particular attention to the poor. At age 14, she prepared for the sacrament of confirmation and showed a deep desire to belong totally to Jesus. She wants to be all His. In this desire, she is counting on Mary’s companionship, convinced that welcoming the maternal care of his Mother, is the surest way to reach Jesus. Conscious of her own impulsive and proud nature, Adele encounters in Mary an excellent model to imitate. With Mary and through the grace of God she can become humble, gentle and patient. Contemplating Mary in the gospels, Adele likes to highlight Mary’s single- heartedness when she corresponds with her friends -"may our heart burn with love for the Lord alone" (35.13); as well as her obedience to the will of God, at whose service she has placed herself entirely ; "I am the handmaid of the Lord!" (35.1); her humility, which has attracted the Lord's gaze and attention, and allowed him to do great things in her, because she surrendered to His will. (287.4); faith, a living faith that has accompanied Mary throughout her life, marked by suffering, by unforeseen events and misunderstandings, and that even brought her to Calvary. -

Nardo Di Cione Madonna and Child

| student + teacher Teacher Notes MUSEUM COLLECTION Nardo di Cione Madonna and Child title Madonna and Child location Gallery 1, Collection Galleries artist Nardo di Cione (Italian, ca. 1320–1365 or 1366) date ca. 1350 medium Tempera and gold leaf on panel size About 2 ½ feet tall and 1 ½ feet wide accession number m1995.679 (detail) FIND MORE TEACHER RESOURCES at MAM.ORG/ LEARN | student + teacher Teacher Notes for classroom use only Nardo di Cione (Italian, ca. 1320–1365 or 1366), Madonna and Child, ca. 1350. Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Purchase, Myron and Elizabeth P. Laskin Fund, Marjorie Tiefenthaler Bequest, Friends of Art, and Fine Arts Society; and funds from Helen Peter Love, Chapman Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. James K. Heller, Joseph Johnson Charitable Trust, the A. D. Robertson Family, Mr. and Mrs. Donald S. Buzard, the Frederick F. Hansen Family, Dr. and Mrs. Richard Fritz, and June Burke Hansen; with additional support from Dr. and Mrs. Alfred Bader, Dr. Warren Gilson, Mrs. Edward T. Tal, Mr. and Mrs. Richard B. Flagg, Mr. and Mrs. William D. Vogel, Mrs. William D. Kyle, Sr., L. B. Smith, Mrs. Malcolm K. Whyte, Bequest of Catherine Jean Quirk, Mrs. Charles E. Sorenson, Mr. William Stiefel, and Mrs. Adelaide Ott Hayes, by exchange m1995.679 | student + teacher Teacher Notes in Florence, Santa Maria Novella. However, artists 23 Find me in 25 26 27 28 29 the galleries! during that time painted not only works of art for churches, but also smaller works of art, such as this 30 31 piece, for individual customers, or patrons.