The Wakan Dialectic As Polemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

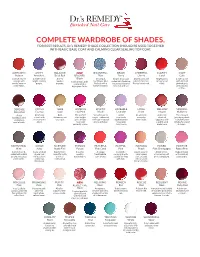

COMPLETE WARDROBE of SHADES. for BEST RESULTS, Dr.’S REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER with BASIC BASE COAT and CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT

COMPLETE WARDROBE OF SHADES. FOR BEST RESULTS, Dr.’s REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER WITH BASIC BASE COAT AND CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT. ALTRUISTIC AMITY BALANCE NEW BOUNTIFUL BRAVE CHEERFUL CLARITY COZY Auburn Amethyst Brick Red BELOVED Blue Berry Cherry Coral Cafe A playful burnt A moderately A deep Blush A tranquil, Bright, fresh and A bold, juicy and Bright pinky A cafe au lait orange with bright, smokey modern Cool cotton candy cornflower blue undeniably feminine; upbeat shimmer- orangey and with hints of earthy, autumn purple. maroon. crème with a flecked with a the perfect blend of flecked candy red. matte. pinkish grey undertones. high-gloss finish. hint of shimmer. romance and fun. and a splash of lilac. DEFENSE FOCUS GLEE HOPEFUL KINETIC LOVEABLE LOYAL MELLOW MINDFUL Deep Red Fuchsia Gold Hot Pink Khaki Lavender Linen Mauve Mulberry A rich A hot pink Rich, The perfect Versatile warm A lilac An ultimate A delicate This renewed bordeaux with classic with shimmery and ultra bright taupe—enhanced that lends everyday shade of juicy berry shade a luxurious rich, romantic luxurious. pink, almost with cool tinges of sophistication sheer nude. eggplant, with is stylishly tart matte finish. allure. neon and green and gray. to springs a subtle pink yet playful sweet perfectly matte. flirty frocks. undertone. & classic. MOTIVATING NOBLE NURTURE PASSION PEACEFUL PLAYFUL PLEASING POISED POSITIVE Mink Navy Nude Pink Purple Pink Coral Pink Peach Pink Champagne Pastel Pink A muted mink, A sea-at-dusk Barely there A subtle, A poppy, A cheerful A pale, peachy- A high-shine, Baby girl pink spiked with subtle shade that beautiful with sparkly fresh bubble- candy pink with coral creme shimmering soft with swirls of purple and cocoa reflects light a hint of boysenberry. -

Red, Crimson, Scarlet) a Word Study By: Jonathan Machtemes (Results from KJV Word Search)

Determining Correct Colors in the Early Scriptures (Red, Crimson, Scarlet) a word study by: Jonathan Machtemes (results from KJV word search) Red H119 adm pass appears: 10x translated as: dyed red, red, ruddy related modern words ?: Lat. adamantem "iron" (produces red), many Euro etymologies on "adam/adem" words are in dispute, damage (in the sense of injury, bloodletting) related obry words: H122 adm- red, ruddy H125 admdm- reddish H132 admny- red, ruddy H1818 dm- blood (of living beings, or of grapes) H120 adm- man, "Adam" of gn odn "garden of Eden" H121 adm- "Adam" of gn odn "garden of Eden", city in knon "Canaan" H124 adm- sardius (stone, gem) H123 adum, adm- owu "Esau", due to Gen 25:30. Also related: H130 admy/ adumym- of adum="Edomite", or adumym="Edomites" pl. H127 adme- ground, or perhaps "Adamkind" (Gen 12:3) and so on passed based, in large part, on dm being the root. dm is blood. Blood is a familiar, naturally occurring substance. d, as bizarrely simplistic as it seems to me at times, seems to often draw one's attention specifically to the fact that it appears as a pointed tip. It's used in ahd- one, unity, bd- apart, or dd- nipple, teat, (also dud- beloved, as in "between the teats" or the emotions). a, on the other hand, seems to act most frequently as an augmentative or giver of strength. Perhaps it is a glyph of a bull, or something with horns. Additionally, the d can be seen in words with the meaning or idea of cutting: H1843 do, H1856 dqr, H1417 gdud, or in directional words od, qdm, H1864 drum. -

Crataegus Laevigata 'Crimson Cloud' 'Crimson Cloud' English Hawthorn

Fact Sheet ST-211 November 1993 Crataegus laevigata ‘Crimson Cloud’ ‘Crimson Cloud’ English Hawthorn1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Crimson Cloud (also known as ‘Superba’) English Hawthorn grows rapidly in a pyramidal form to about 20 feet, then the crown expands to become oval or irregular (Fig. 1). The tree tolerates most soils, growing well in clay, but prefers heavy, dry loam. The main ornamental feature is white and red flowers borne in spring which together give the tree a deep pink color. Fruits are red and quite showy but do not cover the tree. Though quite ornamental, Hawthorns are susceptible to insect and disease problems. Branching habit is decidedly drooping and care should be given when locating this tree near pedestrian or vehicular traffic. GENERAL INFORMATION Figure 1. Middle-aged ‘Crimson Cloud’ English Hawthorn. Scientific name: Crataegus laevigata ‘Crimson Cloud’ Availability: grown in small quantities by a small Pronunciation: kruh-TEE-gus lee-vih-GAY-tuh number of nurseries Common name(s): ‘Crimson Cloud’ English Hawthorn DESCRIPTION Family: Rosaceae USDA hardiness zones: 4B through 8 (Fig. 2) Height: 20 to 25 feet Origin: not native to North America Spread: 15 to 25 feet Uses: Bonsai; espalier; wide tree lawns (>6 feet Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette wide); medium-sized tree lawns (4-6 feet wide); Crown shape: oval; pyramidal recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or Crown density: moderate for median strip plantings in the highway; reclamation Growth rate: medium plant; screen; narrow tree lawns (3-4 feet wide); Texture: fine specimen; sidewalk cutout (tree pit); residential street tree; tree has been successfully grown in urban areas where air pollution, poor drainage, compacted soil, and/or drought are common 1. -

Mr. Nelson's Roses 1856

MR. NELSON'S ROSES, 1856 In The Southern Cultivator, Robert Nelson, a nurseryman of Macon, Georgia, listed the roses he considered best for Southern gardens: China Roses Arch Duke Charles; of very luxuriant growth, and a most prolific bloomer. The flowers are very different in color, varying from light pink to deep crimson, with all the intermediate shades, sometimes, also, marbled and spotted; grows 4 to 5 feet high. Camelliaflora; light rosy purple, in very large clusters; grows about 4 feet high. Carmine Superbe; flowers medium, in great profusion, of a very dark crimson hue, and of a globular form; foliage dark reddish; it forms a neat little hedge. Duchesse of Kent; flowers of medium size, beautifully formed, and in great clusters; color, light pink, or nearly white, with a cream colored centre. It is almost a never-ceasing bloomer, but during the droughts, in summer, the white flowers look as if sprinkled with blood. It grows very compact and bushy--almost dwarfish. Madam Breon; bright rosy crimson, very large and brilliant flowers, which, in the fall, assume a still more brilliant hue. Marjolin; an immense bloomer of a brilliant dark scarlet color and velvety tint. This variety, planted close to "Duchesse of Kent," or planted promiscuously in a hedge, will form a most beautiful object. Lawrenciana; also called the "Picayune" is remarkable for its very small flowers and foliage; it forms a neat edging around beds. Lawrenciana Viridis; the "Green Rose," is a botanical curiosity. The flower, if it can be called so, consists of a greet [sic] tuft of leaves, or, more correctly, in a double calyx, destitute of petals. -

Disperse Dyes

855 Valley Road, Clifton, NJ 07013 | Tel 973.471.3200 | Fax 973.471.3335 | www.americandyestuff.com Disperse Dyes Product Name Color Index Number Amecel Yellow G Disperse Yellow 3 Amecron Yellow 5R Conc Disperse Yellow 23 Amecron Yellow 3GE 200% Disperse Yellow 54 Amecron Yellow 5GE 150% Disperse Yellow 71 Amecron Brilliant Flavine 10GFF Disperse Yellow 82 Amecron Yellow 6GSL 200% Disperse Yellow 114 Amecron Yellow D-7G Disperse Yellow 126 Amecron Yellow GHA Solvent Yellow 163 Amecron Yellow UN-SE 200% Disperse Yellow Amecron Yellow Brown XF Disperse Yellow Amecron Orange 2GR 200% Disperse Orange 25 Amecron Yellow Brown 2RFL Disperse Orange 30 Amecron Orange RL 150% Disperse Orange 37 Amecron Orange SG 200% Disperse Orange 44 Amecron Orange M-5GH Disperse Orange 61 Amecron Orange RSE 125% Disperse Orange 73 Amecron Orange C-O Disperse Orange 76 Amecel Scarlet B Disperse Red 1 Amecel Pink RF Disperse Red 4 Amecel Rubine 3B Disperse Red 5 Amecel Pink FF3B 200% Disperse Red 11 Amecel Bordeaux B 150% Disperse Red 13 Amecel Red YNB Disperse Red 17 Amecron Scarlet 2G-H Disperse Red 50 Amecron Cerise YLN 200% Disperse Red 55 Amecron Red FB 220% Disperse Red 60 Amecel Red RC Disperse Red 88 Amecron Pink REL 200% Disperse Red 91 Amecron Pink BEL 200% Disperse Red 92 Amecron Red BN-SE Disperse Red 127 Amecron Red BS Disperse Red 152 Amecron Scarlet 2R Disperse Red 153 Amecron Red 3BLS Conc. Disperse Red 167 Amecron Rubine BRF Disperse Red 179 Amecron Luminous Red G Disperse Red 277 Amecron Red CBN Disperse Red 356 Amecron Brilliant Red FBS Disperse -

Cultural Practices for Scarlet Royal Jennifer Hashim-Buckey, UCCE Viticulture Farm Advisor and David Ramming, USDA-ARS Research Horticulturist

May-June 2008 Cultural Practices for Scarlet Royal Jennifer Hashim-Buckey, UCCE Viticulture Farm Advisor and David Ramming, USDA-ARS Research Horticulturist Scarlet Royal (US Plant Patent 16,229*) is a mid-season red seedless table grape developed by David Ramming and Ronald Tarailo of the USDA-ARS in Parlier, California. The cultivar, formerly known as B1, was released in 2006 and resulted from the cross of two red seedless USDA selections C33-30 x C51-63. The parentage of Scarlet Royal includes Blackrose, Calmeria, Cardinal, Crimson Seedless, Divizich Early, Italia, Maraville, Muscat of Alexandria, Sultanina and Tafafihi Ahmur. The cultivar produces large (0.8 kg./1.8 lb.), conical-shaped clusters that are medium to well filled. Berries are oval in shape and its appearance is similar to Crimson Seedless. Natural Scarlet Royal berries weigh about 5-7 grams, though berry weight and size is slightly increased when fruit is treated with gibberellic acid. The flesh is firm and meaty and the skin is medium to thick. The flavor is described as sweet and neutral. Scarlet Royal ripens mid-to-late August, filling the harvest window between Flame Seedless and Crimson Seedless. Site Selection and Planting Scarlet Royal is moderately vigorous when planted on its own roots. Rootstock selection should be based on site-specific soil pest or soil chemistry problems. Common rootstock choices for Scarlet Royal have included Freedom and 1103-P, but rootstock effects on fruit yield, quality and vine performance have not yet been evaluated. It is likely that grafting to these and other rootstocks common for table grape production in the San Joaquin Valley will increase vine vigor. -

I~~Yc~~~{::~~C~ ~~~~Rlg! ~F~~~ Per Pkt., 10C

SEED CATALOGUE AND GARDEN GUIDE. GIANT BUGNOT PANSY.-This I PHLOX DRUMMONDI.-If we anese flower in its quaint, yet ar is one of the finest strains of Pan- could have but one flower for our PETUNlfI~, tistic, beau ty . Ed!l'es of petals sies In existence . .The flowers are garden, that one would be the SUl'ely there is no garden com are cut and frlngea In the most of enormous size, perfectly round, Phlox. Its brilliant shades of plete without a bed of elegant complete manne r. In color it is of great substance and of the color. ranging from rlear white to Petunias or a few fine specimen pure white d.t tbe back. wbilst the most \'aried and attractive mark- brilllant scar1et make an almost plauts of It for t he center of beds, fl'iuged edges are of a brilliant iogs and colors; each petal 1?ears dazzling shO\v ; continually In crimson color, Per pkt.. IOc . ._ .J a blo.tch that runs out In delicate bloom. or for growing In pots. For out door decoration or house culture, veins to tbe edge of the petal. Cuspidata or Star.-See Novel- few plants are equal to this class. Per pkt., 25c. ties. Per p kt., l5c. Double Pea r 1.-See Novelties. I~~Yc~~~{::~~c~ ~~~~rlg! ~f~~~ Per pkt., 10c. throughout the wbole season, un til killed by frost; easily culti Grandiflora Alba.-Pure white. vated, requiring rlcb soil and a Pel' pkt., 5c. sunny situation, of late years the Grandiflora Coccinea.- Brilliant Single striped,mottled and double scarlet. -

Approved Tree List

SUGGESTED TREE LIST SMALL TREES Less than 30 feet high at maturity; recommended planting strip should not be less than 2 feet wide. Flowering Crabapples (Spring Snow, Centurion, Harvest Gold, Madonna, Velvet Pillar, Adirondack varieties)-abundant flowers in spring, small fruits in fall. Goldenraintree-feathery, light green foliage. Large clusters of bright yellow flowers emerge in July. Trident Maple-brilliant red fall color, compact head of small, shiny leaves. Hedge Maple-small leaves, single trunk tree. Leprechaun Ash - leaves turn yellow in the fall. Pacific Sunset Maple - leaves turn orange-red in the fall. Sargent Cherry - narrow tree, glossy dark green leaves, small black cherries MEDIUM TREES Less than 45 feet high at maturity; recommended planting strip should not be less than 3 feet wide. Hawthorn (Washington and Winter King varieties)-white flowers in spring followed by small red fruits persisting through winter. Little-Leaf Linden-small dense, dark green foliage and inconspicuous small, fragrant flowers in June; Gieneven and Greenspice varieties recommended. Callery Pear-pyramid tree bearing large masses of white flowers and tiny fruit; fall color is wine red; Redspire and Chaticleer or Cleveland Select varieties recommended. Red Maple (cultivated varieties)-well-formed tree produced colorful, fall foliage. Armstrong is narrow formed; Red Sunset and October Glory varieties are broader in form. Hop Hornbeam-slow growing with dense elm-like foliage; bark peels in thin strips for an attractive appearance. Crimson Maple - leaves are crimson/maroon and do not change color in the fall. Cimmaron Ash - leaves turn dark, brick red in fall. Goldenraintree – feathery, light green foliage. -

Grain Amaranths Amaranthus Spp. (Amaranthaceae)

Grain Amaranths Amaranthus spp. (Amaranthaceae) Klaus Ammann and Jonathan Gressel Manuscript 17. October 2007 Introduction Amaranthus could be a valuable alternative crop due to its high nutritional content, the many desirable traits expressed by the grain amaranths – and the unexplored potential of the wild relatives. Unlike the traditional monocot grains, the grain amaranths possess lysine in nutritionally significant levels. In addition, specific varieties of grain amaranths tolerate drought and heat, and, as a result, lessen the demand for costly irrigation. Peruvian varieties of Amaranthus caudatus have are known for their resistance to damping off and to root rot. Based upon phylogenecic studies (Lanoue et al., 1996) a number of wild species closely related to cultivated Amaranths should be explored for breeding purposes: Amaranthus floridanus and A. pumilus for salt tolerance, A. powellii and A. fimbriatus for drought resistance, and A. hybridus , A. quitensis, and A. retroflexus for pest, viral and bacterial resistance. Not only would these wild species be valuable for breeding with the cultivated Amaranths, but they would also be favourable target species to explore useful genes for other crop traits. Origin and use Amaranths have a long tradition in the New World, where they have been grown as pseudo- cereals by pre-Columbian civilizations on thousands of hectares. In Mesoamerica, amaranth developed as an important ritual and cash crop. They were grown as the principal grain crop by the Aztecs 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, until to the disruption of their culture(s) by the Spanish Conquistadors. The reasons of this decline is still unclear, since the Aztecs relied on the amaranths as an important staple. -

Pink Panther and Crimson Skye

HORTSCIENCE 56(7):853–859. 2021. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI15854-21 containers. Plants of ‘Crimson Skye’ are characterized by compact stature, numerous heart-shaped leaves, multiple pink blotches Two New Lance-leaved Caladium on each leaf, and a high level of uniformity in leaf shape and size. In tuber yield potential, Cultivars: Pink Panther and Crimson ‘Crimson Skye’ is comparable to other lance- leaved cultivars. ‘Crimson Skye’ is well suit- Skye ed for producing high-quality prefinished and finished plants in containers with small (10 Zhanao Deng cm) to large ($20 cm) diameters. Tuber de- University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Science, eyeing is optional; when it is used, it im- Department of Environmental Horticulture, Gulf Coast Research and proves pot plant quality. Both cultivars have shown good sunburn tolerance and bacterial Education Center, 14625 County Road 672, Wimauma, FL 33598 blight disease tolerance, and they are suitable Natalia A. Peres for use in a range of landscape conditions, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Science, from full sun to shady locations. Department of Plant Pathology, Gulf Coast Research and Education Origin Center, 14625 County Road 672, Wimauma, FL 33598 ‘Pink Panther’ originated from a cross be- Johan Desaeger tween ‘Carolyn Whorton’ and a breeding line University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Science, Department UF-4609 that was made in Balm, FL, in Sum- of Entomology and Nematology, Gulf Coast Research and Education Center, mer 2012 (Fig. 5). Breeding line UF-4609 14625 County Road 672, Wimauma, FL 33598 was the progeny of a cross between ‘Cranberry Star’ (initially breeding line 75- Additional index words. -

Melissa Mccormick

Updated 2020/01/29 Melissa McCormick East Asian Languages and Civilizations Department / History of Art and Architecture Department Harvard University ____________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Princeton University, Japanese Art and Archaeology, Ph.D., 2000 University of Michigan, Art History and Japanese, dual B.A. with High Distinction, 1990 Graduate Student Fellow, Japanese Art History, Gakushūin University, Tokyo, 1995-97 Inter-University Center for Japanese Language Studies, Yokohama, Japan, 1990-91 PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY TEACHING Professor of Japanese Art and Culture, Harvard University, 2009 – present John L. Loeb Associate of Professor of the Humanities, Harvard University, 2006–2009 Associate Professor of Japanese Art and Culture, Harvard University, 2005–2006 Itsuko and Takeo Atsumi Assistant Professor of Japanese Art, Columbia University, 2000–05 Visiting Professor, University of Zurich, Department of Art History, October 2019 Visiting Professor, Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Brazil, Getty Foundation “Connecting Art Histories” Program, May – June 2015 MUSEUM WORK Guest Curator, The Tale of Genji: A Japanese Classic Illuminated. International loan exhibition, Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 5 – June 16, 2019. Curatorial Assistant, East Asian Art, University of Michigan Museum of Art, 1987-1990 AWARDS/FELLOWSHIPS/GRANTS Walter Channing Cabot Fellow, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, award for distinguished publications, 2019-20 Harvard College Professorship, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, highest teaching award, 2014-2019 Japan Foundation Research Fellowship, 2013-14 John L. Loeb Associate Professorship of the Humanities, Harvard University 2006-09 American Council of Learned Societies, 2005-06 Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 2005-06 (declined) Japan Foundation Professional Conference Grant, 2004-05 Toshiba International Foundation Fellowship, 2004-05 J. -

Art Archaeology& Newsletter

VET NOV TES TAM PrincetonUniversity EN TVM DEPARTMENT OF Art Archaeology& Newsletter Dear Friends and Colleagues: SPRING We are very pleased to be complet- Asian art history. These included Michael Nylan of Bryn Mawr College and Mike Hearn from the Inside ing the academic year with the Asian Art Department of the Metropolitan inaugural edition of an annual Museum of Art. NEW FACULTY newsletter that will go out to We also completed a successful search for a nineteenth-century position with the appoint- graduate alumni and friends of the ment of Alastair Wright as assistant professor. FACULTY NEWS Department of Art and Archaeol- After receiving his Ph.D. from Columbia in ogy. As with the well-attended , he has been teaching at Richmond Univer- sity in London. He will join us in September GRADUATE STUDENT NEWS reception at the College Art , after a fellowship year at the Getty Insti- Association meeting in New York tute. We are presently carrying out a search for Wen’s replacement, who will hold the first P. Y. EXCAVATIONS in February , its aim is to and Kinmay W. Tang Professorship of Chinese bring us together again and renew and Japanese art. A major concern of the department over the old ties. I am most grateful to MARQUAND LIBRARY NEWS , next few years will be raising funds for the reno- Robert Janson-La Palme * * vation and expansion of Marquand Library. The for assisting us by editing the feasibility study carried out by Shepley, Bulfinch, SLIDES AND PHOTOGRAPHS news from alumni. Richardson, and Abbot is in its final stages.