Logical Positivism and Pragmatism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research Lindsay Mack Abstract This article traces the underlying theoretical framework of educational research. It outlines the definitions of epistemology, ontology and paradigm and the origins, main tenets, and key thinkers of the 3 paradigms; positivist, interpetivist and critical. By closely analyzing each paradigm, the literature review focuses on the ontological and epistemological assumptions of each paradigm. Finally the author analyzes not only the paradigm’s weakness but also the author’s own construct of reality and knowledge which align with the critical paradigm. Key terms: Paradigm, Ontology, Epistemology, Positivism, Interpretivism The English Language Teaching (ELT) field has moved from an ad hoc field with amateurish research to a much more serious enterprise of professionalism. More teachers are conducting research to not only inform their teaching in the classroom but also to bridge the gap between the external researcher dictating policy and the teacher negotiating that policy with the practical demands of their classroom. I was a layperson, not an educational researcher. Determined to emancipate myself from my layperson identity, I began to analyze the different philosophical underpinnings of each paradigm, reading about the great thinkers’ theories and the evolution of social science research. Through this process I began to examine how I view the world, thus realizing my own construction of knowledge and social reality, which is actually quite loose and chaotic. Most importantly, I realized that I identify most with the critical paradigm assumptions and that my future desired role as an educational researcher is to affect change and challenge dominant social and political discourses in ELT. -

The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: a Personal View1

Weber/Editor’s Comments EDITOR’S COMMENTS The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: A Personal View1 Many years ago I attended a conference on interpretive research in information systems. My goal was to learn more about interpretive research. In my Ph.D. education, I had studied primarily positivist research methods—for example, experiments, surveys, and field studies. I knew little, however, about interpretive methods. I hoped to improve my knowledge of interpretive methods with a view to using them in due course in my research work. A plenary session at the conference was devoted to a panel discussion on improving the acceptance of interpretive methods within the information systems discipline. During the session, a number of speakers criticized positivist research harshly. Many members in the audience also took up the cudgel to denigrate positivist research. If any other positivistic researchers were present at the session beside me, like me they were cowed. None of us dared to rise and speak in defence of positivism. Subsequently, I came to understand better the feelings of frustration and disaffection that many early interpretive researchers in the information systems discipline experienced when they attempted to publish their work. They felt that often their research was evaluated improperly and treated unfairly. They contended that colleagues who lacked knowledge of interpretive research methods controlled most of the journals. As a result, their work was evaluated using criteria attuned to positivism rather than interpretivism. My most-vivid memory of the panel session, however, was my surprise at the way positivism was being characterized by my colleagues in the session. -

Logical Empiricism / Positivism Some Empiricist Slogans

4/13/16 Logical empiricism / positivism Some empiricist slogans o Hume’s 18th century book-burning passage Key elements of a logical positivist /empiricist conception of science o Comte’s mid-19th century rejection of n Motivations for post WW1 ‘scientific philosophy’ ‘speculation after first & final causes o viscerally opposed to speculation / mere metaphysics / idealism o Duhem’s late 19th/early 20th century slogan: o a normative demarcation project: to show why science ‘save the phenomena’ is and should be epistemically authoritative n Empiricist commitments o Hempel’s injunction against ‘detours n Logicism through the realm of unobservables’ Conflicts & Memories: The First World War Vienna Circle Maria Marchant o Debussy: Berceuse héroique, Élégie So - what was the motivation for this “revolutionary, written war-time Paris (1914), heralds the ominous bugle call of war uncompromising empricism”? (Godfrey Smith, Ch. 2) o Rachmaninov: Études-Tableaux Op. 39, No 8, 5 “some of the most impassioned, fervent work the composer wrote” Why the “massive intellectual housecleaning”? (Godfrey Smith) o Ireland: Rhapsody, London Nights, London Pieces a “turbulant, virtuosic work… Consider the context: World War I / the interwar period o Prokofiev: Visions Fugitives, Op. 22 written just before he fled as a fugitive himself to the US (1917); military aggression & sardonic irony o Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin each of six movements dedicated to a friend who died in the war x Key problem (1): logicism o Are there, in fact, “rules” governing inference -

Positivism and the Inseparability of Law and Morals

\\server05\productn\N\NYU\83-4\NYU403.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-SEP-08 12:20 POSITIVISM AND THE INSEPARABILITY OF LAW AND MORALS LESLIE GREEN* H.L.A. Hart made a famous claim that legal positivism somehow involves a “sepa- ration of law and morals.” This Article seeks to clarify and assess this claim, con- tending that Hart’s separability thesis should not be confused with the social thesis, the sources thesis, or a methodological thesis about jurisprudence. In contrast, Hart’s separability thesis denies the existence of any necessary conceptual connec- tions between law and morality. That thesis, however, is false: There are many necessary connections between law and morality, some of them conceptually signif- icant. Among them is an important negative connection: Law is, of its nature, morally fallible and morally risky. Lon Fuller emphasized what he called the “internal morality of law,” the “morality that makes law possible.” This Article argues that Hart’s most important message is that there is also an immorality that law makes possible. Law’s nature is seen not only in its internal virtues, in legality, but also in its internal vices, in legalism. INTRODUCTION H.L.A. Hart’s Holmes Lecture gave new expression to the old idea that legal systems comprise positive law only, a thesis usually labeled “legal positivism.” Hart did this in two ways. First, he disen- tangled the idea from the independent and distracting projects of the imperative theory of law, the analytic study of legal language, and non-cognitivist moral philosophies. Hart’s second move was to offer a fresh characterization of the thesis. -

Introduction to Philosophy of Science

INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE The aim of philosophy of science is to understand what scientists did and how they did it, where history of science shows that they performed basic research very well. Therefore to achieve this aim, philosophers look back to the great achievements in the evolution of modern science that started with the Copernicus with greater emphasis given to more recent accomplishments. The earliest philosophy of science in the last two hundred years is Romanticism, which started as a humanities discipline and was later adapted to science as a humanities specialty. The Romantics view the aim of science as interpretative understanding, which is a mentalistic ontology acquired by introspection. They call language containing this ontology “theory”. The most successful science sharing in the humanities aim is economics, but since the development of econometrics that enables forecasting and policy, the humanities aim is mixed with the natural science aim of prediction and control. Often, however, econometricians have found that successful forecasting by econometric models must be purchased at the price of rejecting equation specifications based on the interpretative understanding supplied by neoclassical macroeconomic and microeconomic theory. In this context the term “economic theory” means precisely such neoclassical equation specifications. Aside from economics Romanticism has little relevance to the great accomplishments in the history of science, because its concept of the aim of science has severed it from the benefits of the examination of the history of science. The Romantic philosophy of social science is still resolutely practiced in immature sciences such as sociology, where mentalistic description prevails, where quantification and prediction are seldom attempted, and where implementation in social policy is seldom effective and often counterproductive. -

Anti-Metaphysics: 1. Agnosticism (Qv). 2. Logical Positivism (See Scientific Empiricism (1))

Anti-metaphysics: 1. Agnosticism (q.v.). 2. Logical Positivism (see Scientific Empiricism (1)) holds that those metaphysical statements which are not confirmable by experiences (see Verification 4, 5) have no cognitive meaning and hence are pseudo-statements (see Meaning, Kinds of, 1, 5). — R.C. Basic Sentences, Protocol Sentences: Sentences formulating the result of observations or perceptions or other experiences, furnishing the basis for empirical verification or confirmation (see Verification). Some philosophers take sentences concerning observable properties of physical things as basic sentences, others take sentences concerning sense-data or perceptions. The sentences of the latter kind are regarded by some philosophers as completely verifiable, while others believe that all factual sentences can be confirmed only to some degree. See Scientific Empiricism. — R.C. Formal: l. In the traditional use: valid independently of the specific subject-matter; having a merely logical meaning (see Meaning, Kinds of, 3). 2. Narrower sense, in modern logic: independent of, without reference to meaning (compare Semiotic, 3). — R.C. Intersubjective: Used and understood by, or valid for different subjects. Especially, i. lan- guage, i. concepts, i. knowledge, i. confirmability (see Verification). The i. character of science is especially emphasized by Scientific Empiricism (g. v., 1 C). —R.C. Meaning, Kinds of: In semiotic (q. v.) several kinds of meaning, i.e. of the function of an expression in language and the content it conveys, are distinguished. 1. An expression (sen- tence) has cognitive (or theoretical, assertive) meaning, if it asserts something and hence is either true or false. In this case, it is called a cognitive sentence or (cognitive, genuine) statement; it has usually the form of a declarative sentence. -

The Aesthetic Turn

MARK C. TAYLOR The aesthetic turn his paper considers alternative styles of philoso- because it suggests that there is nothing outside or phy, based on art or science, through an investi- beyond style. Art and style, in turn, are inseparable – Tgation of Rudolf Carnap and Martin Heidegger. there is no art without style and no style without art. Carnap’s criticism of Heidegger’s account of das Nichts The distinction, I am suggesting, is not hard-and-fast. is analysed in relation to Immanuel Kant’s theory of Just as there is a religious dimension to all culture, so the imagination. Heidegger’s account of the work of there is an artistic dimension to all creative thinking; art demonstrates philosophies that take science as and just as religion is often most significant where it is their model, over-emphasize cognition, and do not ad- least obvious, so style is often most influential where equately consider the importance of apprehension. it remains unnoticed, and often denied. The choice, then, is not between style and non-style but between a style that represses its artistic and aesthetic aspects, In 1946, Paul Tillich published a seminal essay and a style that explicitly expresses them. In order to entitled ‘The two types of philosophy of religion’ in explore the differences between these two alterna- which he maintained that every philosophy of reli- tives, I begin by examining the debate between two gion developed in the Christian tradition takes one philosophers whose work has played a crucial role of two forms. While Alfred North Whitehead once in framing the debate for almost a century: Rudolf suggested that everyone is born either a Platonist or Carnap and Martin Heidegger. -

Law and Morality: a Kantian Perspective

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 1987 Law and Morality: A Kantian Perspective George P. Fletcher Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, and the Law and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation George P. Fletcher, Law and Morality: A Kantian Perspective, 87 COLUM. L. REV. 533 (1987). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/1071 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAW AND MORALITY: A KANTIAN PERSPECTIVE George P. Fletcher* The relationship between law and morality has emerged as the cen- tral question in the jurisprudential reflection of our time. Those who call themselves positivists hold with H.L.A. Hart' that calling a statute or a judicial decision "law" need not carry any implications about the morality of that statute or decision.2 Valid laws might be immoral or unjust. Those who resist this reduction of law to valid enactments sometimes argue, with Lon Fuller, that moral acceptability is a neces- sary condition for holding that a statute is law; 3 or, with Ronald Dworkin, that moral principles supplement valid enactments as compo- 4 nents of the law. Whether the positivists or their "moralist" opponents are right about the nature of law, all seem to agree about the nature of morality. We have to distinguish, it is commonly said, between conventional and critical morality. -

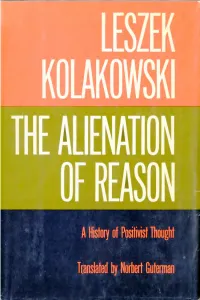

The Alienation of Reason a HISTORY of POSITIVIST THOUGHT .,....O by Leszek Kolakowski

The Alienation of Reason A HISTORY OF POSITIVIST THOUGHT .,....o by Leszek Kolakowski Translated by Norbert Guterman DOUBLEOAY a COMPANY, INC. GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK 1968 Contents Preface V ONE. An Over-all View of Positivism TWO. Positivism Down to David Hume II THREE. Auguste Comte: Positivism in the Romantic Age 47 FOUR. Positivism Triumphant 73 FIVE. Positivism at the Turn of the Ccntury 104 SIX. Conventionalism-Destruction of the Concept of Fact 134 SEVEN. Pragmatism and Positivism 154 EIGHT. Logical Empiricism: A Scientistic Defense of Threatened Gvilization 174 Conclusion 207 Index 221 8 nIE ALIENATION Oll' REASON sense, i.e„ to the cxtent that they teil us what opcrations arc or arc not effcctive in achicving a desircd end. Examplcs of such tcchnical judgmcnts would bc a statement to thc cff cct that we should administer pcnicillin in a case of pncumonia or one to the cffect that children ought not be threatened with a bcating if they won't cat. Such statements can, clearly, be justificd, if thcir mcaning is respectivcly that pcnicillin is an cffectivc rem cdy against pncumonia, and that thrcatcning children with pun ishmcnt to makc them cat causes charactcrological handicaps. And if wc assume tacitly that, as a rulc, it is a good thing to eure the sick and a bad thing to inflict psychic dcformation upon childrcn, the above-mcntioncd statements can be justi.fied, even though thcy do havc thc form of normative judgmcnts. But we are not to assume that any valuc assertion that we rccognizc as truc ''in itsclf," rathcr than in rclation to something eise, can bc justificd by expericnce. -

Passmore, J. (1967). Logical Positivism. in P. Edwards (Ed.). the Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Vol. 5, 52- 57). New York: Macmillan

Passmore, J. (1967). Logical Positivism. In P. Edwards (Ed.). The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Vol. 5, 52- 57). New York: Macmillan. LOGICAL POSITIVISM is the name given in 1931 by A. E. Blumberg and Herbert Feigl to a set of philosophical ideas put forward by the Vienna circle. Synonymous expressions include "consistent empiricism," "logical empiricism," "scientific empiricism," and "logical neo-positivism." The name logical positivism is often, but misleadingly, used more broadly to include the "analytical" or "ordinary language philosophies developed at Cambridge and Oxford. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The logical positivists thought of themselves as continuing a nineteenth-century Viennese empirical tradition, closely linked with British empiricism and culminating in the antimetaphysical, scientifically oriented teaching of Ernst Mach. In 1907 the mathematician Hans Hahn, the economist Otto Neurath, and the physicist Philipp Frank, all of whom were later to be prominent members of the Vienna circle, came together as an informal group to discuss the philosophy of science. They hoped to give an account of science which would do justice -as, they thought, Mach did not- to the central importance of mathematics, logic, and theoretical physics, without abandoning Mach's general doctrine that science is, fundamentally, the description of experience. As a solution to their problems, they looked to the "new positivism" of Poincare; in attempting to reconcile Mach and Poincare; they anticipated the main themes of logical positivism. In 1922, at the instigation of members of the "Vienna group," Moritz Schlick was invited to Vienna as professor, like Mach before him (1895-1901), in the philosophy of the inductive sciences. Schlick had been trained as a scientist under Max Planck and had won a name for himself as an interpreter of Einstein's theory of relativity. -

8897690 Lprob 1.Pdf

CAMBRIDGE AND VIENNA FRANK P. RAMSEY AND THE VIENNA CIRCLE VIENNA CIRCLE INSTITUTE YEARBOOK [2004] 12 VIENNA CIRCLE INSTITUTE YEARBOOK [2004] 12 Institut ‘Wiener Kreis’ Society for the Advancement of the Scientific World Conception Series-Editor: Friedrich Stadler Director, Institut ‘Wiener Kreis’ and University of Vienna, Austria Advisory Editorial Board: Honorary Consulting Editors: Rudolf Haller, University of Graz, Austria, Coordinator Kurt E. Baier Nancy Cartwright, London School of Economics, UK Francesco Barone Robert S. Cohen, Boston University, USA C.G. Hempel † Wilhelm K. Essler, University of Frankfurt/M., Germany Stephan Kö rner † Kurt Rudolf Fischer, University of Vienna, Austria Henk Mulder † Michael Friedman, University of Indiana, Bloomington, USA Arne Naess Peter Galison, Harvard University, USA Paul Neurath † Adolf Grünbaum, University of Pittsburgh, USA Willard Van Orman Quine † Rainer Hegselmann, University of Bayreuth, Germany Marx W. Wartofsky † Michael Heidelberger, University of Tübingen, Germany Jaakko Hintikka, Boston University, USA Review Editor: Gerald Holton, Harvard University, USA Michael Stöltzner Don Howard, University of Notre Dame, USA Allan S. Janik, University of Innsbruck, Austria Editorial Work/Layout/Production: Richard Jeffrey, Princeton University, USA Hartwig Jobst Andreas Kamlah, University of Osnabrück, Germany Camilla R. Nielsen Eckehart Köhler, University of Vienna, Austria Erich Papp Anne J. Kox, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Saul A. Kripke, Princeton University, USA Editorial -

Introduction to Positivism, Interpretivism and Critical Theory

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory Journal Item How to cite: Ryan, Gemma (2018). Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Nurse Researcher, 25(4) pp. 41–49. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.7748/nr.2018.e1466 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Introduction to positivist, interpretivism & critical theory Abstract Background There are three commonly known philosophical research paradigms used to guide research methods and analysis: positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Being able to justify the decision to adopt or reject a philosophy should be part of the basis of research. It is therefore important to understand these paradigms, their origins and principles, and to decide which is appropriate for a study and inform its design, methodology and analysis. Aim To help those new to research philosophy by explaining positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Discussion Positivism resulted from foundationalism and empiricism; positivists value objectivity and proving or disproving hypotheses. Interpretivism is in direct opposition to positivism; it originated from principles developed by Kant and values subjectivity. Critical theory originated in the Frankfurt School and considers the wider oppressive nature of politics or societal influences, and often includes feminist research.