Love and the Ethics of Subaltern Subjectivity in James Joyce's Ulysses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Ja Ne M'en Turnerai Trescque L'avrai Trovez". Ricerche Attorno Al Ms

Ja ne m'en turnerai trescque l'avrai trovez Ricerche attorno al ms. Royal 16 E. VIII, testimone unico del Voyage de Charlemagne à Jérusalem et à Constantinople , e contributi per una nuova edizione del poema Thèse de Doctorat présentée par Carla Rossi devant la Faculté des Lettres de l’Université de Fribourg, en Suisse. Approuvé par la Faculté des Lettres sur proposition des professeurs Aldo Menichetti (premier rapporteur) et Roberto Antonelli (deuxième rapporteur, Università degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza"). Fribourg, le 10/01/2005 Note finale: summa cum laude Le Doyen, Richard Friedli [Copia facsimile della rubrica e dei primi versi del poema, effettuata nel 1832 da F. Michel sul Royal 16 E VIII della BL] Carla ROSSI - Thèse de doctorat - Note finale: summa cum laude 2 Ja ne m'en turnerai trescque l'avrai trovez Ricerche attorno al ms. Royal 16 E. VIII, testimone unico del Voyage de Charlemagne à Jérusalem et à Constantinople , e contributi per una nuova edizione del poema INTRODUZIONE....................................................................................................................................................... 4 PRIMA PARTE 1. Il testimone unico del VdC e Eduard Koschwitz, suo scrupoloso editore................................................... 6 1. 1. Albori degli studi sul poema: "Dieu veuille que cet éditeur soit un Français!"................................... 6 1. 2. Sabato 7 giugno 1879: il testimone unico scompare dalla Sala di Lettura del British Museum........ 11 1. 3. Eduard Koschwitz....................................................................................................................................... -

Official Swoop Gang : Get Off My Shit!

Will Daloz > Official Swoop Gang : Get off my shit! Official Swoop Gang : excuse me? Will Daloz naw, i just mean there's already a swoop gang in atlanta, how you guys gonna be the swoop gang. I can't go around writing and posting and stickering swoop everywhere and have people all pumped for your ninny nonsense Official Swoop Gang pretty sure we are the only swoop gang in atlanta Official Swoop Gang we didnt steal the name, we came up with it last year Official Swoop Gang we have put alot of work into our music, obviously your not listening and only looking at our name. Ryan Schimmel WilD D tellem http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TcxpbhM0DaA Oh Snap ! Peter Stormare The famous oh snap clip from Peter Stormare Will Daloz i googled it and did you know that emory's bird mascot is also named swoop! shit! we're all biting somebody else's genius. Official Swoop Gang honestly we have been saying swoop for awhile, when we came together to start up this project we decided to call ourselves swoop gang cause thats what we always say to each other anyway Official Swoop Gang we have over 100,000 plays on all our tracks and mixes collectively from youtube, blogs and soundcloud in just 2 months. You'll be hearing alot more from us Mark Tway Swoops have been in atlanta for 4 years now, if you go around posting flyering stickering whatever swoop gang people are gonna confuse u with us....I promise you dont want the stigma of being attached to our group. -

The History, Principles and Practice of Symbolism in Christian

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Prince Live in Rotterdam 28.5.1992 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Prince Live In Rotterdam 28.5.1992 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul / Pop Album: Live In Rotterdam 28.5.1992 Style: Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1796 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1322 mb WMA version RAR size: 1434 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 611 Other Formats: DTS MPC AA MP4 MOD MP2 AUD Tracklist 1-1 Intro 4:25 1-2 Thunder 4:12 1-3 Daddy Pop 7:01 1-4 Diamonds And Pearls 6:32 1-5 Let's Go Crazy 2:23 1-6 Kiss 4:53 1-7 Jughead 6:32 1-8 Purple Rain 8:42 1-9 Live 4 Love 6:41 1-10 Willing And Able 6:30 1-11 Damn U 7:16 1-12 Sexy MF 5:32 2-1 Thieves In The Temple / Arabic Instrumental / It 10:46 2-2 A Night In Tunisia 1:59 2-3 Strollin' 0:55 2-4 Insatiable 5:54 2-5 Gett Off 6:12 2-6 Gett Off (Houstyle) 3:25 2-7 The Flow 5:26 2-8 Cream 5:53 2-9 Dr. Feelgood 5:42 2-10 1999 3:39 2-11 Baby I'm A Star 1:09 2-12 Push 3:46 2-13 End Instrumental 2:40 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Ahoy Rotterdam Notes Recording from the 'Diamonds And Pearls' tour held in Rotterdam 1-12 is listed as 'Sexy Mother Fucker' 2-1 is listed as 'Thieves In The Temple' only 2-2 is listed as 'Solo Instrumental' 2-5 & 2-6 are listed as 'Get Off' & 'Get Off II' 2-7 is listed as 'Turn This Mother Out' Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4 162294 001108 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Stagetronic (2xCD, Crystal Cat CC 303-4 Prince CC 303-4 Germany 1992 Unofficial) Records Prince & The New Prince & The Power Generation - SW 20 New Power SW SW 20 Australia 1993 Live Vol. -

Redalyc.On the “Intimate Connivance” of Love and Thought

Eidos: Revista de Filosofía de la Universidad del Norte ISSN: 1692-8857 [email protected] Universidad del Norte Colombia De Chavez, Jeremy On the “Intimate Connivance” of Love and Thought Eidos: Revista de Filosofía de la Universidad del Norte, núm. 26, 2017, pp. 105-120 Universidad del Norte Barranquilla, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=85448897005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Fecha de recepción: octubre 7 de 2015 eidos Fecha de aceptación: mayo 23 de 2016 DOI: ON THE “INTIMATE CONNIVANCE” OF LOVE AND THOUGHT Jeremy De Chavez De La Salle University, Manila [email protected] R ESUMEN El concepto de amor históricamente ha ruborizado a la filosofía, pues se mantiene totalmente ajeno a las exigencias de dar una explicación crítica de sí mismo. El amor ha respondido con resistencia muda a los interrogatorios del pensamiento crítico. De hecho, parece existir un consenso respecto de que el amor se sitúa en un territorio más allá de lo pensable y en la doxa romántica se ha establecido que el amor es un tipo de intensidad que no puede reducirse a ningún principio regulador. Como señala Alain Badiou, es “lo que se sustrae de la teoría”. En este ensayo me opongo a una postura tan antifilosófica y exploro el paren- tesco del amor con el pensamiento y la verdad. -

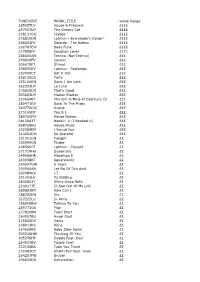

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 285057LV

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 285057LV House & Pressure ££££ 297057LM The Groovy Cat ££££ 298131GQ Jaydee ££££ 276810DN Latmun - Everybody's Dancin' ££££ 268301FV Solardo - The Aztecs ££££ 292787EW Body Funk ££££ 277998FP Egyptian Lover ££££ 286605AN Techno (Not Techno) £££ 276810FV Cosmic £££ 306678FT Strand £££ 296595EV Latmun - Footsteps £££ 252459CT Set It Out £££ 292130GU Party £££ 255100KN Sorry I Am Late £££ 262293LN La Luna £££ 276810DQ That's Good £££ 303663LM Master Blaster £££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Ch £££ 280471KV Back To The Music £££ 323770CW Sueno £££ 273165DT You & I £££ 289765FN House Nation £££ 0412043T Needin' U (I Needed U) £££ 268756KU House Music £££ 292389EM I Found You £££ 314202DM So Grateful £££ 131751GN Tonight ££ 130999GN Finder ££ 296595CT Latmun - Piquant ££ 271719HU Saxomatic ££ 249988HR Moorthon Ii ££ 263938BT Aguardiente ££ 250247GW 9 Years ££ 294966AN Let Go Of This Acid ££ 292489KV 17 ££ 291041LV Ya Kidding ££ 3635852T Shiny Disco Balls ££ 2240177E In And Out Of My Life ££ 269881EM How Can I ££ 188782KN Xtc ££ 327225LU In Arms ££ 156808BW Talking To You ££ 289773GU Play ££ 277820BN False Start ££ 264557BU Angel Dust ££ 215602DR Veins ££ 238913KS Nana ££ 224609BS Baby Slow Down ££ 300216HW Thinking Of You ££ 305278HT Desole Feat. Davi ££ 264557BV Twiple Fwet ££ 232106BS Take You There ££ 272083CP Shakti Pan Feat. Sven ££ 254207FW Bruzer ££ 296650DR Satisfaction ££ 261261AU Burning ££ 2302584E Atlantis ££ 036282DT Don't Stop ££ 309979LN The Tribute ££ 215879HU Devil In Me ££ 290470BR Kubrick -

The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect

PRINCE June 7, 1958 — Third Thursday in April The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect 70s 2000s 1. For You (1978) 24. The Rainbow Children (2001) 2. Prince (1979) 25. One Nite Alone... (2002) 26. Xpectation (2003) 80s 27. N.E.W.S. (2003) 3. Dirty Mind (1980) 28. Musicology (2004) 4. Controversy (1981) 29. The Chocolate Invasion (2004) 5. 1999 (1982) 30. The Slaughterhouse (2004) 6. Purple Rain (1984) 31. 3121 (2006) 7. Around the World in a Day (1985) 32. Planet Earth (2007) 8. Parade (1986) 33. Lotusflow3r (2009) 9. Sign o’ the Times (1987) 34. MPLSound (2009) 10. Lovesexy (1988) 11. Batman (1989) 10s 35. 20Ten (2010) I’VE BEEN 90s 36. Plectrumelectrum (2014) REFERRING TO 12. Graffiti Bridge (1990) 37. Art Official Age (2014) P’S SONGS AS: 13. Diamonds and Pearls (1991) 38. HITnRUN, Phase One (2015) ALBUM : SONG 14. (Love Symbol Album) (1992) 39. HITnRUN, Phase Two (2015) P 28:11 15. Come (1994) IS MY SONG OF 16. The Black Album (1994) THE MOMENT: 17. The Gold Experience (1995) “DEAR MR. MAN” 18. Chaos and Disorder (1996) 19. Emancipation (1996) 20. Crystal Ball (1998) 21. The Truth (1998) 22. The Vault: Old Friends 4 Sale (1999) 23. Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic (1999) DONATE TO MUSIC EDUCATION #HonorPRN PRINCE JUNE 7, 1958 — THIRD THURSDAY IN APRIL THE ULTIMATE LISTENING-RETROSPECT 051916-031617 1 1 FOR YOU You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ me away 1 For You 2. In Love (In love) April 7, 1978 Ever since I met you, baby I’m fallin’ baby, girl, what can I do? I’ve been wantin’ to lay you down I just can’t be without you But it’s so hard to get ytou Baby, when you never come I’m fallin’ in love around I’m fallin’ baby, deeper everyday Every day that you keep it away (In love) It only makes me want it more You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ Ooh baby, just say the word me away And I’ll be at your door (In love) And I’m fallin’ baby. -

Jeremy De Chavez De La Salle University, Manila [email protected]

Fecha de recepción: octubre 7 de 2015 eidos Fecha de aceptación: mayo 23 de 2016 DOI: ON THE “INTIMATE CONNIVANCE” OF LOVE AND THOUGHT Jeremy De Chavez De La Salle University, Manila [email protected] R ESUMEN El concepto de amor históricamente ha ruborizado a la filosofía, pues se mantiene totalmente ajeno a las exigencias de dar una explicación crítica de sí mismo. El amor ha respondido con resistencia muda a los interrogatorios del pensamiento crítico. De hecho, parece existir un consenso respecto de que el amor se sitúa en un territorio más allá de lo pensable y en la doxa romántica se ha establecido que el amor es un tipo de intensidad que no puede reducirse a ningún principio regulador. Como señala Alain Badiou, es “lo que se sustrae de la teoría”. En este ensayo me opongo a una postura tan antifilosófica y exploro el paren- tesco del amor con el pensamiento y la verdad. Basado principalmente en la obra de Jean-Luc Nancy y Alain Badiou, sondeo la relación entre amor y pensamiento, pues ello constituye una ocasión para que nos percatemos de la “connivencia íntima entre el amor y el pensar”, en palabras de Nancy. En un momento en que el amor se ve amenazado por acusaciones de no ser nada más que un “optimismo cruel”, sugiero que Nancy y Badiou hacen una defensa filosófica del amor al subrayar su parentesco con el pensamiento y la verdad. P ALABRAS CLAVE : amor, Nancy, Badiou, afectividad. A BST R A C T The concept of love has historically been somewhat of an embarrassment for Philosophy because it remains relentlessly oblivious to the demands for it to present a critical account of itself. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT of NEW JERSEY V

, UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CRIMINAL COMPLAINT v. The Honorable Steven C. Mannion DENNIS WRIGHT, a/k/a "Hersh," a/k/a "Coyote," Mag. No. 15-6090 MILTON LATHAM, a/k/a "Murder," GABRIEL HENDERSON, FILED UNDER SEAL a/k/a "Gabe," VINCENT J. CARTER, a/k/a "Vince," a/k/a "Vin," AHMAD MANN, a/k/a "P .0." a/k/a "P-Easy," SHAROD BROWN, a/k/a "Hot Rod," a/k/a "Sharod Caraway," and LARRY COLEMAN, a/k/a "LA" I, the undersigned complainant, being duly sworn, state the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. SEE ATTACHMENT A I further state that I am a Special Agent with the Federal Bureau oflnvestigation and that this criminal complaint is based on the following facts: SEE ATTACHMENT B continued on the auached page and made a part hereof. ifacl1e1 Kolvek Special Agent Federal Bureau oflnvestigation Sworn to before me and subscribed in my presence, May 18, 2015 at Newark, New Jersey THE HONORABLE STEVEN C. MANNION UNITED STATES M AG ISTRATE JUDGE Signature of Judicial Officer ATTACHMENT A Count One (Conspiracy to Distribute, and Possess with Intent to Distribute, Heroin) Between in or about December 2014 and on or about May 20, 2015, in Essex County, in the District of New Jersey and elsewhere, defendants DENNIS WRIGHT, aJk/a "Hersh," aJk/a "Coyote," MILTON LATHAM, aJk/a "Murder," GABRIEL HENDERSON, aJk/a "Gabe," VINCENT J. CARTER, aJk/a "Vince," aJk/a "Vin," AHMAD MANN, aJk/a "P.O." aJk/a ''P-Easy," SHAROD BROWN, aJk/a "Hot Rod," aJk/a "Sharod Caraway," and LARRY COLEMAN, aJk/a "LA," did knowingly and intentionally conspire with each other and others to distribute, and possess with intent to distribute, 100 grams or more of a mixture and substance containing a detectable amount of heroin, a Schedule I controlled substance, contrary to Title 21, United States Code, Sections 841(a)(l) and (b)(l)(B). -

The Spirit of the Sword and Spear

The Spirit of the Sword and Spear The Spirit of the Sword and Spear Mark Pearce From the Norse sagas or the Arthurian cycles, we are used to the concept that the warrior’s weapon has an identity, a name. In this article I shall ask whether some prehistoric weapons also had an identity. Using case studies of La Tène swords, early Iron Age central and southern Italian spearheads and middle and late Bronze Age type Boiu and type Sauerbrunn swords, I shall argue that prehistoric weapons could indeed have an identity and that this has important implications for their biographies, suggesting that they may have been conserved as heirlooms or exchanged as prestige gifts for much longer than is generally assumed, which in turn impacts our understanding of the deposition of weapons in tombs, where they may have had a ‘guardian spirit’ function. There are many ways in which we can approach the persons and events to which it is connected’. They prehistoric weapons (Pearce 2007): we can study them illustrate this point through Trobriand kula exchange. typologically, to see how their form is related to the In this article I shall take an approach which sequence of types, and we can also use that informa- is related to this latter trend, but rather than try to tion to date them, assigning them to chronological examine the biography of some prehistoric swords horizons. We can examine them functionally, and try and spears, I want to pose the question: was an identity to assess how effective they will have been as weap- attributed to some prehistoric weapons? By using the ons, or perhaps as parade paraphernalia rather than term ‘identity’ I do not mean to argue that prehistoric utilitarian equipment. -

The Subject of Jouissance: the Late Lacan and Gender and Queer Theories

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 The Subject of Jouissance: The Late Lacan and Gender and Queer Theories Frederic C. Baitinger The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3243 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SUBJECT OF JOUISSANCE: THE LATE LACAN AND GENDER AND QUEER THEORIES by FRÉDÉRIC BAITINGER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in the French Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 FRÉDÉRIC BAITINGER !ii All Rights Reserved The Subject of Jouissance: The Late Lacan and Gender and Queer Theories by Frédéric Baitinger This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in the French Program in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 03 / 21 / 2019 Royal S. Brown ————————— ———————————————— Date Chair of Examining Committee 03 / 21 / 2019 Maxime Blanchard ————————— ———————————————— Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Royal S. Brown Francesca Canadé Sautman Raphaël Liogier !iii THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ABSTRACT The Subject of Jouissance: The Late Lacan and Gender and Queer Theories by Frédéric Baitinger Adviser: Royal S. Brown The Subject of Jouissance argues that Lacan’s approach to psychoanalysis, far from being heteronormative, offers a notion of identity that deconstructs gender as a social norm, and opens onto a non-normative theory of the subject (of jouissance) that still remains to be fully explored by feminist, gender, and queer scholars. -

Queen Victoria, Her Life and Empire

il^^Pl^g: m 4 o 4 O ^<.. a? ^ •> s € > *;•- ^^^ o « . V. R. I. gUEEN VICTORIA HER LIFE AND EMPIRE BY THE MARQUIS OF T ORNE (now his grace the duke of Argyll) ILLUSTRATED NEW YORK AND LONDON HARPER S- BROTHERS PUBLISHERS 1901 THF LIBRARY Of OCMGRESS, Two Cui-iEci HecEivEn NOV. y 1901 COFVmOHT ENTRY CLM£ii)<a^XXc. No. copY a. 1 Brothers, Limited. Copyright, 1901, by Harmsworth All rights reserved. November, igoi. PREFACE A PREFACE is an old-fashioned thing, we are told, and yet modern publishers repeat the demand made by their brethren of Queen Victoria's early days, and declare that one is wanted. If this be so, I am glad to take the opportunity thus given to me to thank the publishers for the quickness and completeness with which the matter printed in the following pages was issued. Nowadays there are so many able writers in the field of literary activity writing volumes, or ar- ticles in the newspapers or magazines, that very rapid work is necessary if a man desires to impress readers with his views of a character or of an event, before the public have listened to others. The long waiting, pondering, collating, and weighing, fit for the final labor of the historian, is impossible to him who rapidly sketches in his subject for the eyes of the genera- tion which desires an immediate survey of the imme- diate past. We may deplore the fact that great themes cannot thus be worthily treated. The facts that are already public are alone those that may be dwelt upon.