Swansea University Open Access Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City and County of Swansea Scrutiny Programme

CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA NOTICE OF MEETING You are invited to attend a Meeting of the SCRUTINY PROGRAMME COMMITTEE At: Committee Room 2, Civic Centre, Swansea On: Monday, 11 March, 2013 Time: 4.30 pm AGENDA Page No. 1. Apologies for Absence. 2. To receive Disclosures of Personal and Prejudicial Interests. 1 3. To approve the Minutes of the Scrutiny Programme Committee 2 - 11 held on 11 February 2013. 4. Crime & Disorder Scrutiny: Performance of Safer Swansea 12 - 69 Partnership - Presentation followed by Questions to Co-Chairs of the Partnership: • Chief Superintendent Julian Williams (South Wales Police) • Reena Owen (Corporate Director – Environment) 5. Follow Up on Previous Scrutiny Reports: 70 - 82 a) Swansea City Centre (first follow up) (Joint Report of the Cabinet Members for Place and Regeneration) 6. Single Integrated Plan Consultation: a) Report Back from Councillor Consultation Seminar on Swansea's New 83 - 94 Single Integrated Plan. b) Scrutiny Arrangements for Swansea Local Service Board. 95 - 98 7. Annual Self Evaluation - Education Services to Children and 99 - 187 Young People 2012-2013. 8. Scrutiny Work Programme: 188 - 201 a) The Committee Work Plan. b) Progress on Informal Scrutiny Panels and Working Groups. 9. Scrutiny Letters: a) Letter to / from Cabinet Member for Well Being re. Child & Family 202 - 208 Services Performance Panel. b) Letter to / from Cabinet Member for Place re. Local Flood Risk 209 - 215 Management Scrutiny Working Group. 10. Date and Time of Future Meetings for 2012/13 Municipal Year (all on Mondays at 4.30 p.m.) - 8 April 2013. Patrick Arran Head of Legal, Democratic Services & Procurement Monday, 4 March 2013 Contact: Samantha Woon - Tel: (01792) 637292 Agenda Item 2 Disclosures of Personal Interest from Members To receive Disclosures of Personal Interest from Members in accordance with the provisions of the Code of Conduct adopted by the City and County of Swansea. -

Environment Template (REF5) Institution: Swansea University: Prifysgol Abertawe Unit of Assessment: 28B - Modern Languages and Linguistics (Celtic Studies) A

Environment template (REF5) Institution: Swansea University: Prifysgol Abertawe Unit of Assessment: 28b - Modern Languages and Linguistics (Celtic Studies) a. Overview Staff included in this Unit of Assessment are based within Academi Hywel Teifi or affiliated to it. Established in 2010, it champions the Welsh language throughout the University and includes the Welsh for Adults Centre for south-west Wales and the former Department of Welsh. The research of the Unit specifically focuses on three fields in relation to the Welsh language: its literature, its cultural media and applied linguistics, with more staff currently involved in the first field. The Unit is supported in all activities by the wider structures of the College of Arts and Humanities (COAH). COAH is home to the Research Institute for Arts and Humanities (RIAH) and its Graduate Centre. COAH’s large team of nine staff – director, assistant director, research and administrative officers – support Academi researchers and postgraduates. Two members of the Academi sit on its Management Board and the College’s Research committee. A member of the Academi currently directs the Graduate Centre. Since RAE 2008, these new structures have dramatically transformed the research environment of Welsh and Welsh studies at Swansea for the better. The Unit runs its own seminar series, Seminar y Gymraeg, organised by Academi Hywel Teifi and attended by colleagues from several departments. In addition to Seminar y Gymraeg, our researchers within the Unit are active members of other COAH interdisciplinary research centres and groups, including the Centre for Research into the English Language and Literature of Wales (CREW) and the Language Research Centre (LRC), and attend events with a Celtic Studies theme at other centres such as the Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Research (MEMO). -

The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust Half

THE GLAMORGAN-GWENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST High Street Presumed layout of burgage plots Outer Ditch High Street Excavated section of outer Bailey ditch Presumed line of medieval town wall Ditch awe Goat Street Goat Medieval course Old of River Tawe Castle River T New Castle Cross Street Wind Street St Mary's Church 14th century St David's hospital preserved as part of Fisher Street the Cross Keys public house Areas of 13th and 14th Century pits Line of medieval boundary ditch GRID for Swansea's N 0 100metres lower suburb HALF-YEARLY REVIEW 2010 & ANNUAL REVIEW OF PROJECTS 2009-2010 STE GI RE E D The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust Ltd R O I A R N Heathfield House Heathfield Swansea SA1 6EL G IO A N ISAT Cover images from top: The ‘wandering wall’ on Cefn Car. Part of a stone inscription, probably a tombstone, referring to an ‘unjust fate’. It was found in the debris of the tower building shown below it. Aerial close-up of the herring-bone stone foundations of the tower building discovered during the building of a new coach park near Celtic Manor. Plan showing the ‘old’ and ‘new’ Swansea Castle and the probable medieval town layout. The reverse (tail side) of an extremely rare Henry 1 silver penny, struck in Pembroke probably between 1115 and 1120. This is the earliest coin yet found in Swansea. A 19th century worker’s house in a small settlement of at least five houses and a barn at Ffos-y-fran near Merthyr Tydfil. The settlement is thought to date back to the mid- 18th century when the Dowlais Ironworks was established. -

Welsh-Medium and Bilingual Education

WELSH-MEDIUM AND BILINGUAL EDUCATION CATRIN REDKNAP W. GWYN LEWIS SIAN RHIANNON WILLIAMS JANET LAUGHARNE Catrin Redknap leads the Welsh Language Board pre-16 Education Unit. The Unit maintains a strategic overview of Welsh-medium and bilingual education and training. Before joining the Board she lectured on Spanish and Sociolinguistics at the University of Cardiff. Gwyn Lewis lectures in the College of Education and Lifelong Learning at the University of Wales, Bangor, with specific responsibility for Welsh language education within the primary and secondary teacher training courses. A joint General Editor of Education Transactions, his main research interests include Welsh-medium and bilingual education, bilingualism and child language development. Sian Rhiannon Williams lectures on History at the University of Wales Institute Cardiff. Her research interests include the history of women in the teaching profession and other aspects of the history of education in Wales. Based on her doctoral thesis, her first book was a study of the social history of the Welsh language in industrial Monmouthshire. She has published widely on the history of Gwent and on women’s history in Wales, and has co- edited a volume on the history of women in the south Wales valleys during the interwar period. She is reviews editor of the Welsh Journal of Education. Janet Laugharne lectures in the Cardiff School of Education, University of Wales Institute Cardiff, and is the School’s Director of Research. She is interested in bilingualism and bilingual education and has written on this area in relation to Welsh, English and other community languages in Britain. She is one of the principal investigators for a project, commissioned by the Welsh Assembly Government, to evaluate the implementation of the new Foundation Stage curriculum for 3-7 year-olds in Wales. -

961 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

961 bus time schedule & line map 961 Llansamlet - Swansea College via Winch Wen View In Website Mode The 961 bus line Llansamlet - Swansea College via Winch Wen has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Tycoch: 7:38 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 961 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 961 bus arriving. Direction: Tycoch 961 bus Time Schedule 59 stops Tycoch Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:38 AM Church Road, Llansamlet 141 Samlet Road, Swansea Tuesday 7:38 AM Lon-Las School, Gwernllwynchwyth Wednesday 7:38 AM Walters Road Roundabout, Gwernllwynchwyth Thursday 7:38 AM Friday 7:38 AM Walters Road, Felin Fran Walters Road, Llansamlet Community Saturday Not Operational Ynysallan Road, Heol-Las Heol Las, Heol-Las 961 bus Info Smiths Road, Birchgrove Direction: Tycoch Stops: 59 Heol Dulais, Heol-Las Trip Duration: 53 min Line Summary: Church Road, Llansamlet, Lon-Las Heol Dulais Corner, Birchgrove School, Gwernllwynchwyth, Walters Road Roundabout, Gwernllwynchwyth, Walters Road, Felin Heol Dulais, Birchgrove Community Fran, Ynysallan Road, Heol-Las, Heol Las, Heol-Las, School, Birchgrove Smiths Road, Birchgrove, Heol Dulais, Heol-Las, Heol Dulais Corner, Birchgrove, School, Birchgrove, Bridgend Inn, Birchgrove, Birchgrove Road, Bridgend Inn, Birchgrove Birchgrove, Birchgrove Stores, Birchgrove, Birchgrove Hill, Peniel Green, Peniel Green East, Birchgrove Road, Birchgrove Peniel Green, Library, Peniel Green, Llansamlet Railway Station, Peniel Green, Llansamlet -

City and County of Swansea West Glamorgan Archives Committee

CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA NOTICE OF MEETING You are invited to attend a Meeting of the WEST GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES COMMITTEE At: Committee Room 2, Civic Cent re, Swansea. On: Thursday, 12 December 2013 Time: 11.00 am AGENDA Page No. 1 To receive any Apologies for Absence. 2 To receive Disclosures of Personal and Prejudicial Interests from Members. 3 To approve and sign the Minutes of the West Glamorgan Archives 1 - 4 Committee held on 13 September 2013 as a correct record. 4 To consider the Report of the County Archivist. 5 - 23 5 Date of Meetings for 2013/14. 14 th March (Neath) - 11.00am. Patrick Arran Head of Legal, Democratic Services & Procurement 5 December 2013 Contact: Gareth Borsden - 01792 636824 Agenda Item 3 CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA NEATH PORT TALBOT COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE WEST GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES COMMITTEE HELD AT THE CIVIC CENTRE, PORT TALBOT ON FRIDAY 13 SEPTEMBER 2013 AT 11.00 A.M. PRESENT : Councillor D W Davies (Vice-Chair) presided Representatives of the City and County of Swansea : Councillor(s) : Councillor(s) : P M Meara R V Smith Representatives of Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council : Councillor(s) : Councillor(s) : Councillor(s) : J Dudley P A Rees A Wingrave Representatives of the Associated Organisations : Canon S J Ryan - Diocese of Llandaff Mrs J L Watkins - Neath Antiquarian Society Officers : K Collis, D Michael, W John and G Borsden 13. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence were received from Mr D B Lewis (Lord Lieutenant), Councillors K E Marsh, J A Raynor, C Thomas and Venerable R Williams and Dr L Miskell. -

36 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

36 bus time schedule & line map 36 Swansea City Centre - Morriston View In Website Mode The 36 bus line (Swansea City Centre - Morriston) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Morriston: 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM (2) Swansea: 6:32 AM - 9:52 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 36 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 36 bus arriving. Direction: Morriston 36 bus Time Schedule 28 stops Morriston Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:50 AM - 10:50 PM Monday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM Bus Station J, Swansea Tuesday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM St Mary`S Church B, Swansea Saint Mary's Square, Swansea Wednesday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM High Street 1, Swansea Thursday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM 5-6 High Street, Swansea Friday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM High Street Station, Swansea Saturday 8:50 AM - 10:50 PM Dyfatty, Hafod 143-144 High Street, Swansea Zoar Chapel, Waun Wen 36 bus Info Carmarthen Road, Swansea Direction: Morriston Stops: 28 Waun Wen Inn, Waun Wen Trip Duration: 37 min Line Summary: Bus Station J, Swansea, St Mary`S Cwmfelin Club, Cwmbwrla Church B, Swansea, High Street 1, Swansea, High Mansel Terrace, Swansea Street Station, Swansea, Dyfatty, Hafod, Zoar Chapel, Waun Wen, Waun Wen Inn, Waun Wen, Robert Street, Brondeg Cwmfelin Club, Cwmbwrla, Robert Street, Brondeg, Richard Street, Swansea Elgin Street East, Brondeg, Manselton Hotel, Manselton, Brynhyfryd Square, Manselton, Parkhill Elgin Street East, Brondeg Road, Penƒlia, Community Centre, Treboeth, Visteon 103 Manselton Road, Swansea Club, Tirdeunaw, Caersalem Cross, -

Report on the Examination Into the Swansea Local Development Plan 2010 – 2025

Adroddiad i Gyngor Report to Swansea Abertawe Council gan: by: Rebecca Phillips BA (Hons) MSc DipM Rebecca Phillips BA (Hons) MSc DipM MRTPI MCIM MRTPI MCIM Paul Selby BEng (Hons) MSc MRTPI Paul Selby BEng (Hons) MSc MRTPI Arolygyddion a benodir gan Weinidogion Inspectors appointed by the Welsh Cymru Ministers Dyddiad: 31/01/19 Date: 31/01/19 PLANNING AND COMPULSORY PURCHASE ACT 2004 (AS AMENDED) SECTION 64 REPORT ON THE EXAMINATION INTO THE SWANSEA LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2010 – 2025 Plan submitted for examination on 28 July 2017 Hearings held 6 February – 28 March 2018 and 10 – 11 September 2018 Cyf ffeil/File ref: 515477 Swansea Local Development Plan 2010-2025 – Inspectors’ Report Abbreviations used in this report AA Appropriate Assessment AONB Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty AQMA Air Quality Management Area CBEEMS Carmarthen Bay and Estuaries European Marine Site DAMs Development Advice Maps DCWW Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water FCA Flood Consequences Assessment HRA Habitats Regulations Assessment IDP Infrastructure Delivery Plan IMAC Inspectors’ Matters Arising Change LDP Local Development Plan LHMA Local Housing Market Assessment LPA Local Planning Authority LSA Local Search Area MAC Matters Arising Change MoU Memorandum of Understanding NRW Natural Resources Wales PPW Planning Policy Wales RSL Registered Social Landlord SA Sustainability Appraisal SCARC Swansea Central Area Retail Centre SCARF Swansea Central Area Regeneration Framework SDA Strategic Development Area SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment SHPZ Strategic Housing Policy -

HEFCW Circular W20/09HE: Annex B 1 Research Wales Innovation Fund

HEFCW circular W20/09HE: Annex B Research Wales Innovation Fund Strategy 2020/21 – 2022/23 Institution: Swansea University RWIF strategy lead: Prof. Marcus Doel, Deputy PVC – Research & Innovation Prof. Martin Stringer, PVC – Student Experience & Civic Mission Emma Dunbar- Head of Engagement, Innovation, Employability & Enterprise, REIS Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Telephone : 07860736047 (Emma Dunbar) Section A: Overview 1. Strategic ambitions Please provide an overview of your institution’s 3 year [and beyond if longer term plans are available] approach to research and innovation activity which will be supported by RWIF. You may wish to highlight broad areas which you are targeting, and describe how RWIF funding will align with your institutional mission and internal strategies. [max 300 words] This 3 year strategy comes at a particular moment in our history, when celebrating our centenary, we have had to come together as a community in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. We will use this opportunity to reflect on what we might achieve over the next few years that will resonate for our second century. We are proud to belong to the City of Swansea and the wider Swansea Bay City Region (SBCR) and we celebrate that heritage. We will strengthen our position within the SBCR, as the region’s major university, with the quality and scale of research and innovation to facilitate powerful strategic collaborations between universities, government funding bodies, our extensive SME network, large companies, and their supply chains; and to deliver transformational economic and social benefits both within Wales, the UK and across the rest of the world. -

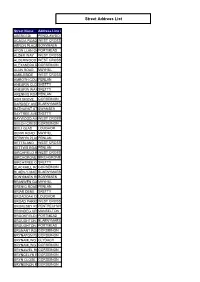

Street Address List

Street Address List Street Name Address Line 2 ABERCEDI PENCLAWDD ACACIA ROAD WEST CROSS AERON PLACEBONYMAEN AFON LLAN GARDENSPORTMEAD ALDER WAY WEST CROSS ALDERWOOD ROADWEST CROSS ALEXANDRA ROADGORSEINON ALUN ROAD MAYHILL AMBLESIDE WEST CROSS AMROTH COURTPENLAN ANEURIN CLOSESKETTY ANEURIN WAYSKETTY ARENNIG ROADPENLAN ASH GROVE GORSEINON BARDSEY AVENUEBLAENYMAES BATHURST STREETSWANSEA BAYTREE AVENUESKETTY BAYWOOD AVENUEWEST CROSS BEECH CRESCENTGORSEINON BEILI GLAS LOUGHOR BERW ROAD MAYHILL BERWYN PLACEPENLAN BETTSLAND WEST CROSS BETTWS ROADPENLAN BIRCHFIELD ROADWEST CROSS BIRCHGROVE ROADBIRCHGROVE BIRCHTREE CLOSESKETTY BLACKHILL ROADGORSEINON BLAEN-Y-MAESBLAENYMAES DRIVE BONYMAEN ROADBONYMAEN BRANWEN GARDENSMAYHILL BRENIG ROAD PENLAN BRIAR DENE SKETTY BROADOAK COURTLOUGHOR BROAD PARKSWEST CROSS BROKESBY ROADPENTRECHWYTH BRONDEG CRESCENTMANSELTON BROOKFIELD PLACEPORTMEAD BROUGHTON AVENUEBLAENYMAES BROUGHTON AVENUEPORTMEAD BRUNANT ROADGORSEINON BRYNAFON ROADGORSEINON BRYNAMLWG CLYDACH BRYNAMLWG ROADGORSEINON BRYNAWEL ROADGORSEINON BRYNCELYN ROADGORSEINON BRYN CLOSE GORSEINON BRYNEINON ROADGORSEINON BRYNEITHIN GOWERTON BRYNEITHIN ROADGORSEINON BRYNFFYNNONGORSEINON ROAD BRYNGOLAU GORSEINON BRYNGWASTADGORSEINON ROAD BRYNHYFRYD ROADGORSEINON BRYNIAGO ROADPONTARDULAIS BRYNLLWCHWRLOUGHOR ROAD BRYNMELIN STREETSWANSEA BRYN RHOSOGLOUGHOR BRYNTEG CLYDACH BRYNTEG ROADGORSEINON BRYNTIRION ROADPONTLLIW BRYN VERNEL LOUGHOR BRYNYMOR THREE CROSSES BUCKINGHAM ROADBONYMAEN BURRY GREENLLANGENNITH BWLCHYGWINFELINDRE BYNG STREET LANDORE CABAN ISAAC ROADPENCLAWDD -

Adroddiad Blynyddol 1979

ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL / ANNUAL REPORT 1978-79 J D K LLOYD 1979001 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Mr J D K Lloyd, O.B.E., D.L., M.A., LL.D., F.S.A., Garthmyl, Powys. Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1978-79 Disgrifiad / Description Two deed boxes containing papers of the late Dr. J. D. K. Lloyd (1900-78), antiquary, author of A Guide to Montgomery and of various articles on local history, formerly mayor of Montgomery and high sheriff of Montgomeryshire, and holder of several public and academic offices [see Who's Who 1978 for details]. The one box, labelled `Materials for a History of Montgomery', contains manuscript volumes comprising a copy of the glossary of the obsolete words and difficult passages contained in the charters and laws of Montgomery Borough by William Illingworth, n.d. [watermark 1820), a volume of oaths of office required to be taken by officials of Montgomery Borough, n.d., [watermark 1823], an account book of the trustees of the poor of Montgomery in respect of land called the Poors Land, 1873-96 (with map), and two volumes of notes, one containing notes on the bailiffs of Montgomery for Dr. Lloyd's article in The Montgomeryshire Collections, Vol. 44, 1936, and the other containing items of Montgomery interest extracted from Archaeologia Cambrensis and The Montgomeryshire Collections; printed material including An Authentic Statement of a Transaction alluded to by James Bland Burgess, Esq., in his late Address to the Country Gentlemen of England and Wales, 1791, relating to the regulation of the practice of county courts, Letters to John Probert, Esq., one of the devisees of the late Earl of Powis upon the Advantages and Defects of the Montgomery and Pool House of Industry, 1801, A State of Facts as pledged by Mr. -

A Comparative Critical Study of Kate Roberts and Virginia Woolf

CULTURAL TRANSLATIONS: A COMPARATIVE CRITICAL STUDY OF KATE ROBERTS AND VIRGINIA WOOLF FRANCESCA RHYDDERCH A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PhD UNIVERSITY OF WALES, ABERYSTWYTH 2000 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. 4" Signed....... (candidate) ................................................. z3... Zz1j0 Date x1i. .......... ......................................................................... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) ......... ' .................................................... ..... 3.. MRS Date X11.. U............................................................................. ............... , STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. hL" Signed............ (candidate) .............................................. 3Ü......................................................................... Date.?. ' CULTURAL TRANSLATIONS: A COMPARATIVE CRITICAL STUDY OF KATE ROBERTS AND VIRGINIA WOOLF FRANCESCA RHYDDERCH Abstract This thesis offers a comparative critical study of Virginia Woolf and her lesser known contemporary, the Welsh author Kate Roberts. To the majority of