Can I Have a Taste of Your Ice Cream? Lucy O’Brien, Goldsmiths College, University of London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Exploration of Charges of Racism Made Against the 1970S UK

This is an author pre-print of an article published in Women’s Studies International Forum. The definitive publisher-authenticated version Mackay Finn (2014) ‘Mapping The Routes: An exploration of charges of racism made against 1970s UK Reclaim the Night marches’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 44, pp. 46-54 is available online at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277539514000521 Mapping the Routes: An exploration of charges of racism made against the 1970s UK Reclaim the Night marches This article addresses early charges of racism, made against the original UK Reclaim the Night (RTN) marches in the 1970s. These charges appear to have stuck, and been accepted almost as a truism ever since, being maintained in several academic texts. Using archive materials, and recent, empirical qualitative research with founding RTN activists and participants, I shall investigate the emergence of RTN in the UK in 1977 and the practicalities and influences behind this type of protest. I will also consider possible reasons behind the charges of racism, addressing justifiable critiques and concerns. I will conclude that the specific charges made against the first RTN marches were inaccurate. However, I will also explore possible reasons why concerns about racism surrounded these marches at their formation. Introduction In this article I shall trace the emergence of the Reclaim the Night (RTN) march in the UK in 1977 and explore charges of racism made against the protest soon after its founding; which have been frequently repeated since. RTN is traditionally a women-only, night time, urban protest march against all forms of male violence against women. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

Male and Female Murderers in Newspapers: Are They Portrayed Differently?

Male and female murderers in newspapers: Are they portrayed differently? Bethany O’Donnell Email: [email protected] Abstract This research aims to identify any similarities and differences in the reporting of male and female murderers in broadsheet and tabloid newspapers. In order to gain a stronger insight into the issue, two case studies have been selected, one male and one female. Through the method of thematic analysis, this article examines how the female serial murderer Joanna Dennehy was represented compared with the male serial murderer Stephen Griffiths in a selection of articles from national newspapers. During this process, reoccurring themes were discovered that are discussed in the analysis. These themes are ‘labelling’ and ‘blaming others’. ‘Labelling’ is divided into sub- themes of ‘mental illness’ and ‘sexualisation and de-humanisation’. The aforementioned themes are discussed in the analysis. It was found that the gender of a serial murderer does dictate how they are portrayed in tabloid newspapers. This is also true for broadsheet newspapers to a lesser extent. For example, this research shows that Joanna Dennehy is represented as mentally ill, whereas this is not as prominent for Stephen Griffiths, despite him committing similar acts. Furthermore, Dennehy is de-humanised in both types of newspaper, although to a greater degree in tabloid newspapers. It was discovered that Griffiths was not subjected to the same de-humanisation. These findings concur with previous research outlined in the literature review, though the themes mentioned in the discussion do not occur as blatantly as some researchers suggest they do for other female murderers in the media. -

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

Reed First Pages

4. Northern England 1. Progress in Hell Northern England was both the center of the European industrial revolution and the birthplace of industrial music. From the early nineteenth century, coal and steel works fueled the economies of cities like Manchester and She!eld and shaped their culture and urban aesthetics. By 1970, the region’s continuous mandate of progress had paved roads and erected buildings that told 150 years of industrial history in their ugly, collisive urban planning—ever new growth amidst the expanding junkyard of old progress. In the BBC documentary Synth Britannia, the narrator declares that “Victorian slums had been torn down and replaced by ultramodern concrete highrises,” but the images on the screen show more brick ruins than clean futurescapes, ceaselessly "ashing dystopian sky- lines of colorless smoke.1 Chris Watson of the She!eld band Cabaret Voltaire recalls in the late 1960s “being taken on school trips round the steelworks . just seeing it as a vision of hell, you know, never ever wanting to do that.”2 #is outdated hell smoldered in spite of the city’s supposed growth and improve- ment; a$er all, She!eld had signi%cantly enlarged its administrative territory in 1967, and a year later the M1 motorway opened easy passage to London 170 miles south, and wasn’t that progress? Institutional modernization neither erased northern England’s nineteenth- century combination of working-class pride and disenfranchisement nor of- fered many genuinely new possibilities within culture and labor, the Open Uni- versity notwithstanding. In literature and the arts, it was a long-acknowledged truism that any municipal attempt at utopia would result in totalitarianism. -

Stories of Women's Fear During the 'Yorkshire Ripper' Murders Louise

Exploring Gender and Fear Retrospectively: Stories of Women’s Fear during the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ Murders Louise Wattis* Department of Criminology, School of Social Sciences and Law, Teesside University, United Kingdom Clarendon Building Teesside University Borough Road Middlesbrough, United Kingdom Ts5 6ew (44) 1642 384463 [email protected] Ackn: N CN: Y Word count: 9103 Exploring Gender and Fear Retrospectively: Stories of Women’s Fear during the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ Murders Abstract The murder of 13 women in the North of England between 1975 and 1979 by Peter Sutcliffe who became known as the Yorkshire Ripper can be viewed as a significant criminal event due to the level of fear generated and the impact on local communities more generally. Drawing upon oral history interviews carried out with individuals living in Leeds at the time of the murders, this article explores women’s accounts of their fears from the time. This offers the opportunity to explore the gender/fear nexus from the unique perspective of a clearly defined object of fear situated within a specific spatial and historical setting. Findings revealed a range of anticipated fear-related emotions and practices which confirm popular ‘high-fear’ motifs; however, narrative analysis of interviews also highlighted more nuanced articulations of resistance and fearlessness based upon class, place and biographies of violence, as well as the way in which women drew upon fear/fearlessness in their overall construction of self. It is argued that using narrative approaches is a valuable means of uncovering the complexity of fear of crime and more specifically provides renewed insight onto women’s fear. -

Weirdo Canyon Dispatch 2018

Review: Roadburn Thursday 19th April 2017 By Sander van den Driesche It’s that time of the year again, the After Yellow Eyes it’s straight to the much anticipated annual pilgrimage to Main Stage to see Dark Buddha Rising Tilburg to join with many hundreds of perform with Oranssi Pazuzu as the travellers for Walter’s party at Waste of Space Orchestra, which is Roadburn. As I get off the train the another highly anticipated show, and in heat kicks me right in the face, what a this case one that won’t be played massive difference to the dull and rainy anywhere else (as far as I know). What morning I left behind in Scotland. This happened on that big stage was is glorious weather for a Roadburn phenomenal, we witnessed a near hour Festival! Bring it on! of glorious drone-infused psychedelic proggy doom. In fact, it felt a bit too early for me personally in the timing of the festival to experience such an extraordinarily mind-blowing set, but it was a remarkable collaboration and performance. I can’t wait for the Live at Roadburn release to come out (someone make it happen please!). Yellow Eyes by Niels Vinck After getting my bearings with the new venues, I enter Het Patronaat for the first of my highly anticipated performances of the festival, Yellow Eyes. But after three blistering minutes of ferocious black metal the PA system seems to disagree and we have our first “Zeal & Ardor moment” of 2018. It’s Waste of Space Orchestra by Niels Vinck not even remotely funny to see the On the same Main Stage, Earthless Roadburn crew frantically trying to played the first of their sets as figure out what went wrong, but luckily Roadburn’s artist in residence. -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

VIDEO and POP Paul Morley

May 1983 Marxism Today 37 VIDEO AND POP Paul Morley attention pop receives for multiples of wickedness, ridicule, discontent, eccentric ity, desire to thrive importantly in a genuinely popular context. Pop music can play a large part in the way numerous young people determine their right to desire and their need to question. It appeared that pop music's contem porary value was to be its creation or proposition of constant new values. Rock music — a period stretched from Elvis Presley to the last moment before The Sex Pistols coughed up Carry On Artaud — was easily appropriated by an establishment, the elegant apparatus of conservatism, that yearns for order. It was hoped that post-punk pop music, freed of the demands of over-excited hippies and usefully paranoiac, would evolve as some thing abstract, fluid, careering, irreverent, slippery, exaggerated — not on a revolu tionary mission, but non-static, not mean, a focus that supplies energy, as provocative and as changeable as essentially nostalgic twentieth century entertainment can be. A ringing variation. No destination, but a purpose. The video dumps us back into the most sinister part of the pop music game. In terms of pop as arousal the video takes us back to that moment before The Sex Pistols bawled louder than all the sur rounding banality. The moment of mundane disappointment. Some of us try an often brilliant best to resources can emerge that can help the The arrival, or at least the pop industry's prove to outsiders and cynics that pop audience release themselves from the misuse, of the video is a major reason, or music — what used to be known as rock unrelieving confinements of environment. -

Issue 117.Pmd

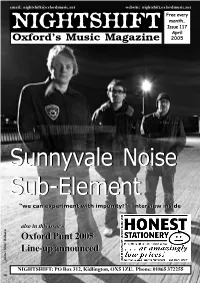

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 117 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SunnyvaleSunnyvale NoiseNoise Sub-ElementSub-Element “we“we cancan experimentexperiment withwith impunity!”impunity!” -- interviewinterview insideinside alsoalso inin thisthis issueissue -- OxfordOxford PuntPunt 20052005 Line-upLine-up announcedannounced photo: Miles Walkden photo: Miles NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE LINE-UP FOR THIS YEAR’S OXFORD PUNT HAS BEEN finalised. The Punt takes place on Wednesay 11th May and features 24 local bands and solo artists playing across eight venues on one night. The Punt is now established as the best showcase of local unsigned music. This year Nightshift received over 100 demos from local acts hoping to take part. The Punt received an added boost last month when Kiss Bar became the eighth venue to be added to the event, meaning we could fit an extra three bands on the bill, making this the biggest Punt ever. The full line up is as follows: Borders: 6.15pm: Laima Bite; 7pm: Kate Chadwick. Jongleurs: 7.30: The Evenings; 8.15: A Silent Film; 9pm: The Factory THE YOUNG KNIVES release a new EP on May 16th on hot new indie Far From The Madding Crowd (in conjunction with Delicious Music): label Transgressive, the label that launched The Subways earlier this 8.15: Zoe Bicat; 9.15: The Thumb Quintet; 10.15: Chantelle Pike. year. Tracks on the limited 10” EP are ‘Coastgard’, ‘Kramer Vs The City Tavern: 8.30: The Half Rabbits; 9.30: Fell City Girl; 10.30: Kramer’, ‘Weekends And Bleak days’ and ‘Trembling Of The Trails’, all Junkie Brush. -

B Au H Au S Im a G Inis Ta E X H Ib Itio N G U Ide Bauhaus Imaginista

bauhaus imaginista bauhaus imaginista Exhibition Guide Corresponding p. 13 With C4 C1 C2 A D1 B5 B4 B2 112 C3 D3 B4 119 D4 D2 B1 B3 B D5 A C Walter Gropius, The Bauhaus (1919–1933) Bauhaus Manifesto, 1919 p. 24 p. 16 D B Kala Bhavan Shin Kenchiku Kōgei Gakuin p. 29 (School of New Architecture and Design), Tokyo, 1932–1939 p. 19 Learning p. 35 From M3 N M2 A N M3 B1 B2 M2 M1 E2 E3 L C E1 D1 C1 K2 K K L1 D3 F C2 D4 K5 K1 G D1 K5 G D2 D2 K3 G1 K4 G1 D5 I K5 H J G1 D6 A H Paul Klee, Maria Martinez: Ceramics Teppich, 1927 p. 57 p. 38 I B Navajo Film Themselves The Bauhaus p. 58 and the Premodern p. 41 J Paulo Tavares, Des-Habitat / C Revista Habitat (1950–1954) Anni and Josef Albers p. 59 in the Americas p. 43 K Lina Bo Bardi D and Pedagogy Fiber Art p. 60 p. 45 L E Ivan Serpa From Moscow to Mexico City: and Grupo Frente Lena Bergner p. 65 and Hannes Meyer p. 50 M Decolonizing Culture: F The Casablanca School Reading p. 66 Sibyl Moholy-Nagy p. 53 N Kader Attia G The Body’s Legacies: Marguerite Wildenhain The Objects and Pond Farm p. 54 Colonial Melancholia p. 70 Moving p. 71 Away H G H F1 I B J C F A E D2 D1 D4 D3 D3 A F Marcel Breuer, Alice Creischer, ein bauhaus-film. -

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction” by the Rolling Stones (1965) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by Dan Leroy (Guest Post)*

“(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction” by the Rolling Stones (1965) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by Dan LeRoy (guest post)* The Rolling Stones Not long before his untimely death in February 2020, guitarist Andy Gill of the British post-punk band Gang of Four was reminiscing about his love of The Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction.” “That riff!” Gill enthused. “It was perfect. Every morning when I went to school, and every night when I came home, I marched along to it.”1 Former Gang of Four singer Jon King had innumerable disputes with his old bandmate. But on the subject of “Satisfaction,” the two had long ago reached a satisfying equilibrium. “I doubt there’s many rock music fans who don’t revere ‘Satisfaction,’” King observed. His description of the song’s attributes was admirably succinct: “Killer riff, spare, focused with intense and deep lyrics about alienation in a new consumer culture.” That two post-punk legends like Gill and King would revere “Satisfaction” is hardly a surprise. The divide between old-guard bands like the Stones and the then-new wave in Britain was never as pronounced as it first appeared. But what made the song singular in its time is, paradoxically, what also makes it universal, today and forevermore. More than any other song of its era, it embodies discontent and alienation--and not just the sort beginning to surface in the mid-Sixties. 1 After Gill’s death, an interview with the journalist and author Dan Epstein surfaced in “Flood” magazine. In that previously-unpublished conversation from a few years prior, Gill revealed that he had auditioned for Jagger’s band in the mid-Eighties, and that in rehearsal, he upstaged an outraged Jeff Beck by talking the guitar solo in “Miss You.” A number one single on both sides of the Atlantic in the summer of 1965, it captured the “rumbling of rebellion,” as guitarist Keith Richards put it, and became the Stones’ signature hit for nearly half a decade, until “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” arrived to supplant it as the decade changed.