Husbandry Guidelines For: Bush Stone-Curlew Burhinus Grallarius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Best of Queensland Experiences Program

2019 Best of Queensland Experiences Program Congratulations to the 2019 Best of Queensland Experiences, who exceed consumer expectations and help us to show travellers why Queensland is truly ‘the best address on earth’. Products Operator Destination @ Verandahs Boutique Apartments Tropical North Queensland 1770 LARC! Tours Gladstone 1770 Liquid Adventures Gladstone 1770reef Great Barrier Reef Eco Tours Gladstone 2 Day 1 Night Whitsundays Sailing Adventures Whitsundays 201 Lake Street Tropical North Queensland 2nd Avenue Beachside Apartments Gold Coast 3 Bedroom Holiday House Tropical North Queensland 31 The Rocks Southern Queensland Country 4WD G'day Adventure Tours Brisbane A Cruise for Couples - Explore Whitsundays Whitsundays A Cruise for Couples - Whitsundays Sailing Adventures Whitsundays AAT Kings Guided Holidays (Queensland) Tropical North Queensland Abajaz Motor Inn Outback Queensland Abbey of the Roses Southern Queensland Country Abbey Of The Roses Country House Manor Southern Queensland Country Abell Point Marina Whitsundays Above and Below Photography Gallery Whitsundays Absolute Backpackers Mission Beach Tropical North Queensland Absolute North Charters Townsville Accom Whitsunday Whitsundays Accommodation Creek Cottages Southern Queensland Country Adina Apartment Hotel Brisbane Anzac Square Brisbane Adrenalin Snorkel and Dive Townsville Adventure Catamarans - Whitsundays Sailing Adventures Whitsundays Adventure Catamarans and Yachts - ISail Whitsundays Whitsundays Adventure Cruise and Sail – Southern Cross Sailing Whitsundays -

Phylogenetic Reanalysis of Strauch's Osteological Data Set for The

TheCondor97:174-196 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1995 PHYLOGENETIC REANALYSIS OF STRAUCH’S OSTEOLOGICAL DATA SET FOR THE CHARADRIIFORMES PHILIP c. CHU Department of Biology and Museum of Zoology The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Abstract. Strauch’s (1978) compatibility analysisof relationshipsamong the shorebirds (Charadriifonnes) was the first study to examine the full range of charadriifonn taxa in a reproducibleway. SubsequentlyMickevich and Parenti (1980) leveled seriouscharges against Strauch’s characters,method of phylogenetic inference, and results. To account for these charges,Strauch ’s characterswere re-examined and recoded, and parsimony analyseswere performed on the revised matrix. A parsimony analysison 74 taxa from the revised matrix yielded 855 shortesttrees, each length = 286 and consistencyindex = 0.385. In each shortest tree there were two major lineages,a lineageof sandpiper-likebirds and a lineageof plover- like birds; the two formed a monophyletic group, with the auks (Alcidae) being that group’s sister taxon. The shortest trees were then compared with other estimates of shorebird re- lationships, comparison suggestingthat the chargesagainst Strauch’s results may have re- sulted from the Mickevich and Parenti decisions to exclude much of Strauch’s character evidence. Key words: Charadrilformes; phylogeny; compatibility analysis: parsimony analysis; tax- onomic congruence. INTRODUCTION Strauch scored 227 charadriiform taxa for 70 The investigation of evolutionary relationships characters. Sixty-three of the characters were among shorebirds (Aves: Charadriiformes) has a taken from either the skull or postcranial skel- long history (reviewed in Sibley and Ahlquist eton; the remaining seven involved the respec- 1990). Almost all studies used morphology to tive origins of three neck muscles, as published make inferences about shared ancestry; infer- in Burton (1971, 1972, 1974) and Zusi (1962). -

Bush Stone-Curlew Husbandry Manual

bush stone-curlew husbandry manual File Name: bush stone-curlew husbandry manual.pdf Size: 3996 KB Type: PDF, ePub, eBook Category: Book Uploaded: 22 May 2019, 22:19 PM Rating: 4.6/5 from 569 votes. Status: AVAILABLE Last checked: 8 Minutes ago! In order to read or download bush stone-curlew husbandry manual ebook, you need to create a FREE account. Download Now! eBook includes PDF, ePub and Kindle version ✔ Register a free 1 month Trial Account. ✔ Download as many books as you like (Personal use) ✔ Cancel the membership at any time if not satisfied. ✔ Join Over 80000 Happy Readers Book Descriptions: We have made it easy for you to find a PDF Ebooks without any digging. And by having access to our ebooks online or by storing it on your computer, you have convenient answers with bush stone- curlew husbandry manual . To get started finding bush stone-curlew husbandry manual , you are right to find our website which has a comprehensive collection of manuals listed. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. Home | Contact | DMCA Book Descriptions: bush stone-curlew husbandry manual Indian stone curlew morphologically characterized by sandy black bill, large yellow eyes and prominent black and white wing bars. The nest was found to build on furrowed soil with fine clay, gravel or sand having free drainage during the months of March and April. The vegetation in breeding ground mainly comprised of species of Family Amaranthaceae, Solanaceae, Malvaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Polygonaceae and Asteraceae. During the breeding both the parents defend breeding ground against their natural enemies by maintaining the nest territory of 100 meters. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

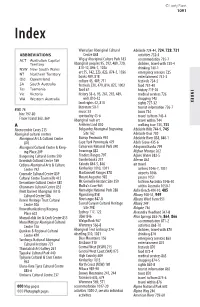

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Spotted Tailed Quoll (Dasyurus Maculatus)

Husbandry Guidelines for the SPOTTED-TAILED QUOLL (Tiger Quoll) (Photo: J. Marten) Dasyurus maculatus (MAMMALIA: DASYURIDAE) Author: Julie Marten Date of Preparation: February 2013 – June 2014 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: Captive Animals Certificate III (18913) Lecturers: Graeme Phipps, Jacki Salkeld, Brad Walker DISCLAIMER Please note that this information is just a guide. It is not a definitive set of rules on how the care of Spotted- Tailed Quolls must be conducted. Information provided may vary for: • Individual Spotted-Tailed Quolls • Spotted-Tailed Quolls from different regions of Australia • Spotted-Tailed Quolls kept in zoos versus Spotted-Tailed Quolls from the wild • Spotted-Tailed Quolls kept in different zoos Additionally different zoos have their own set of rules and guidelines on how to provide husbandry for their Spotted-Tailed Quolls. Even though I researched from many sources and consulted various people, there are zoos and individual keepers, researchers etc. that have more knowledge than myself and additional research should always be conducted before partaking any new activity. Legislations are regularly changing and therefore it is recommended to research policies set out by national and state government and associations such as ARAZPA, ZAA etc. Any incident resulting from the misuse of this document will not be recognised as the responsibility of the author. Please use at the participants discretion. Any enhancements to this document to increase animal care standards and husbandry techniques are appreciated. Otherwise I hope this manual provides some helpful information. Julie Marten Picture J.Marten 2 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS It is important before conducting any work that all hazards are identified. -

Waterbirds of Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh with Special Reference to White-Bellied Heron Ardea Insignis

Rec. zool. Surv. India: l08(Part-3) : 109-118, 2008 WATERBIRDS OF NAMDAPHA TIGER RESERVE, ARUNACHAL PRADESH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO WHITE-BELLIED HERON ARDEA INSIGNIS GOPINATHAN MAHESW ARAN* Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053, India INTRODUCTION Namdapha Tiger Reserve has a rich aquatic bird fauna, mostly because of many freshwater lakes/ponds located at higher altitudes as well as within the evergreen forest patches and the complex river system it has. While surveys were carried out by the research team of the Zoological Survey of India (Ghosh, 1987) from March 1981 to March 1987, the following prominent waterbirds were recorded from Namdapha : Goliath Heron Ardea goliath, Large Egret Casmerodius albus, Chinese Pond Heron Ardeola bacchus, Little Egret Egretta garzetta, Common Merganser Mergus Inerganser, Eastern Marsh Harrier Circus spilonotus, and at least seven species of kingfishers, beside the migrant Common Teal Anas crecca. However, the team did not record any White-bellied Heron. Interestingly, I did not record Goliath Heron during my surveys in two years, which the team did so. The White-bellied Heron Ardea insignis (Family : Ardeidae) is a little known species occurring in swamps, marshes and forests from Nepal through Sikkim, Bhutan and northeast Assam in India to Bangladesh, Arakan and north Bunna (Walters 1976). According to Ali and Ripley (1987), it is a highly endangered species and restricted to undisturbed reed ~eds and marshes in eastern Nepal and the Sikkim terai, Bihar (north of the Ganges river), Bhutan duars to northern Assam, Bangladesh, Arakan and north Burma (= Myanmar). In Assam, it has been reported from Kaziranga National Park (Barua and Sharma 1999), Jamjing and Bordoloni of Dhemaji district (Choudhury 1990, 1992, 1994), Dibru-Saikhowa Wildlife Sanctuary and Biosphere Reserve (Choudhury 1994), Pobitara Wildlife Sanctuary (Choudhury 1996a, Baruah et al. -

Master Index

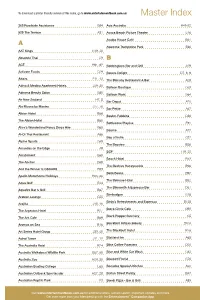

To download a printer friendly version of this index, go to www.entertainmentbook.com.au Master Index 365 Roadside Assistance G84 Avis Australia H49-52 529 The Terrace A31 Avoca Beach Picture Theatre E46 Awaba House Café B61 A Awezone Trampoline Park E66 AAT Kings H19, 20 Absolute Thai C9 B ACE H61, 62 Babbingtons Bar and Grill A29 Activate Foods G29 Bakers Delight D7, 8, 9 Adairs F11, 12 The Balcony Restaurant & Bar A28 Adina & Medina Apartment Hotels J29, 30 Balloon Boutique G63 Adnama Beauty Salon G50 Balloon Worx G64 Air New Zealand H7, 8 Bar Depot A20 Ala Moana by Mantra J77, 78 Bar Petite A67 Albion Hotel B66 Baskin-Robbins D36 The Albion Hotel B60 Battlezone Playlive E91 Alice’s Wonderland Fancy Dress Hire G65 Baume A77 Al-Oi Thai Restaurant A66 Bay of India C37 Alpine Sports G69 The Bayview B56 Amandas on the Edge A9 BCF F19, 20 Amazement E69 Beach Hotel B13 The Anchor B68 The Beehive Honeysuckle B96 And the Winner Is OSCARS B53 Bella Beans B97 Apollo Motorhome Holidays H65, 66 The Belmore Hotel B52 Aqua Golf E24 The Bikesmith & Espresso Bar D61 Aqua re Bar & Grill B67 Bimbadgen G18 Arabian Lounge C25 Birdy’s Refreshments and Espresso B125 Arajilla J15, 16 Black Circle Cafe B95 The Argenton Hotel B27 Black Pepper Butchery G5 The Ark Cafe B69 Aromas on Sea B16 Blackbird Artisan Bakery B104 Art Series Hotel Group J39, 40 The Blackbutt Hotel B76 Astral Tower J11, 12 Blaxland Inn A65 The Australia Hotel B24 Bliss Coffee Roasters D66 Australia Walkabout Wildlife Park E87, 88 Blue and White Car Wash G82 Australia Zoo H29, 30 Bluebird Florist G76 Australian Boating College E65 Bocados Spanish Kitchen A50 Australian Outback Spectacular H27, 28 Bolton Street Pantry B47 Australian Reptile Park E3 Bondi Pizza - Bar & Grill A85 Visit www.entertainmentbook.com.au for additional offers, suburb search, important updates and more. -

SPOTTED-TAILED QUOLL (Tiger Quoll)

Husbandry Guidelines for the SPOTTED-TAILED QUOLL (Tiger Quoll) (Photo: J. Marten) Dasyurus maculatus (MAMMALIA: DASYURIDAE) Date By From Version 2014 Julie Marten WSI Richmond v 1 DISCLAIMER Please note that this information is just a guide. It is not a definitive set of rules on how the care of Spotted- Tailed Quolls must be conducted. Information provided may vary for: Individual Spotted-Tailed Quolls Spotted-Tailed Quolls from different regions of Australia Spotted-Tailed Quolls kept in zoos versus Spotted-Tailed Quolls from the wild Spotted-Tailed Quolls kept in different zoos Additionally different zoos have their own set of rules and guidelines on how to provide husbandry for their Spotted-Tailed Quolls. Even though I researched from many sources and consulted various people, there are zoos and individual keepers, researchers etc. that have more knowledge than myself and additional research should always be conducted before partaking any new activity. Legislations are regularly changing and therefore it is recommended to research policies set out by national and state government and associations such as ARAZPA, ZAA etc. Any incident resulting from the misuse of this document will not be recognised as the responsibility of the author. Please use at the participants discretion. Any enhancements to this document to increase anima l care standards and husbandry techniques are appreciated. Otherwise I hope this manual provides some helpful information. Julie Marten Picture J.Marten 2 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS It is important before conducting any work that all hazards are identified. This includes working with the animal and maintaining the enclosure. -

Download the Annual Report 2019-2020

Leading � rec�very Annual Report 2019–2020 TARONGA ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 A SHARED FUTURE � WILDLIFE AND PE�PLE At Taronga we believe that together we can find a better and more sustainable way for wildlife and people to share this planet. Taronga recognises that the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems are the life support systems for our own species' health and prosperity. At no time in history has this been more evident, with drought, bushfires, climate change, global pandemics, habitat destruction, ocean acidification and many other crises threatening natural systems and our own future. Whilst we cannot tackle these challenges alone, Taronga is acting now and working to save species, sustain robust ecosystems, provide experiences and create learning opportunities so that we act together. We believe that all of us have a responsibility to protect the world’s precious wildlife, not just for us in our lifetimes, but for generations into the future. Our Zoos create experiences that delight and inspire lasting connections between people and wildlife. We aim to create conservation advocates that value wildlife, speak up for nature and take action to help create a future where both people and wildlife thrive. Our conservation breeding programs for threatened and priority wildlife help a myriad of species, with our program for 11 Legacy Species representing an increased commitment to six Australian and five Sumatran species at risk of extinction. The Koala was added as an 11th Legacy Species in 2019, to reflect increasing threats to its survival. In the last 12 months alone, Taronga partnered with 28 organisations working on the front line of conservation across 17 countries. -

Annual Report 2015–2016

120 ANNUAL REPORT 2015–2016 Appendices JOURNEY TO THE FUTURE 121 ContentsAppendix 1 Functions of the Taronga Conservation Society Australia ........................................................................................................................................................122 Appendix 2 Privacy Management ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................122 Appendix 3 Conservation Programs and Population Management Programs ........................................................................................................................................123 Appendix 4 Animal transactions relating to Conservation Programs and Population Management Programs ....................................................................124 Appendix 5 Research projects and conservation programs ...............................................................................................................................................................................126 Appendix 6 Post-mortem and clinical samples supplied for research and teaching purposes .........................................................................................................133 Appendix 7 Scientific associates .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................134 -

Australian Animal Care and Management Industry Sector

Australian Animal Care and Management Industry Sector Annual Update 2021 IRC Skills Forecast and Proposed Schedule of Work Prepared on behalf of the Animal Care and Management Industry Reference Committee (IRC) and Pharmaceutical Manufacturing IRC for the Australian Industry Skills Committee (AISC). Contents Purpose of the Annual Update ............................................................................................................................ 3 Method & Structure .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Industry Reference Committee ............................................................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Section A: Overview ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Industry Developments .................................................................................................................................... 6 VET Qualifications & Employment Outcomes ................................................................................................. 9 Other Training Used by Employers ................................................................................................................ 10 Enrolment