The Spreckels Organ Pavilion in Balboa Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View PDF Editionarrow Forward

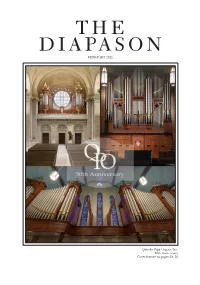

THE DIAPASON FEBRUARY 2021 Quimby Pipe Organs, Inc. 50th Anniversary Cover feature on pages 18–20 PHILLIP TRUCKENBROD CONCERT ARTISTS ADAM J. BRAKEL THE CHENAULT DUO PETER RICHARD CONTE LYNNE DAVIS ISABELLE DEMERS CLIVE DRISKILL-SMITH DUO MUSART BARCELONA JEREMY FILSELL MICHAEL HEY HEY & LIBERIS DUO CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN DAVID HURD MARTIN JEAN BÁLINT KAROSI JEAN-WILLY KUNZ HUW LEWIS RENÉE ANNE LOUPRETTE ROBERT MCCORMICK JACK MITCHENER BRUCE NESWICK ORGANIZED RHYTHM RAÚL PRIETO RAM°REZ JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN BENJAMIN SHEEN HERNDON SPILLMAN JOSHUA STAFFORD CAROLE TERRY JOHANN VEXO W͘K͘ŽdžϰϯϮ ĞĂƌďŽƌŶ,ĞŝŐŚƚƐ͕D/ϰဒϭϮϳ ǁǁǁ͘ĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ ĞŵĂŝůΛĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ ဒϲϬͲϱϲϬͲϳဒϬϬ ŚĂƌůĞƐDŝůůĞƌ͕WƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚ WŚŝůůŝƉdƌƵĐŬĞŶďƌŽĚ͕&ŽƵŶĚĞƌ BRADLEY HUNTER WELCH SEBASTIAN HEINDL INSPIRATIONS ENSEMBLE ϮϬϭဓ>ÊĦóÊÊ'ÙÄÝ /ÄãÙÄã®ÊĽKÙ¦Ä ÊÃÖã®ã®ÊÄt®ÄÄÙ THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Twelfth Year: No. 2, 20 Under 30 Whole No. 1335 We thank the many people who submitted nominations for FEBRUARY 2021 our 20 Under 30 Class of 2021. Nominations closed on Feb- Established in 1909 ruary 1. We will reveal our awardees in the May issue, with Stephen Schnurr ISSN 0012-2378 biographical information and photographs! 847/954-7989; [email protected] www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, A gift subscription is always appropriate. the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music Remember, a gift subscription of The Diapason for a In this issue friend, colleague, or student is a gift that is remembered each Gunther Göttsche surveys organs and organbuilding in the CONTENTS month. (And our student subscription rate cannot be beat at Holy Land. There are approximately sixty pipe organs in this FEATURES $20/year!) Subscriptions can be ordered by calling our sub- region of the world. -

The Spreckels Mansion

THE SPRECKELS MANSION HISTORIC BEACH HOME At the time the house was built in the early 20th century, most of the homes being built in Coronado were Victorian-style architecture, constructed out of wood with an ornate design. At the time John D. Spreckels built his beach house, a mix of humble Italian Renaissance Revival and Beaux-Arts architectural styles, it stood in stark contrast to the neighboring homes. Today, it is one of the city’s few remaining examples possessing the distinctive characteristics of construction using reinforced concrete that has not been substantially altered. The 17,990 square-foot compound—nearly one-half acre, built on three contiguous 6,000 square-foot lots, includes a main house, a guest house and caretakers living quarters for a total of 12,750 square feet with a total of nine bedrooms, eight full bathrooms and three half bathrooms. The 6,600 square-foot main house originally featured six bedrooms, a Main House 1940’s basement and an attic has been modernized and restored to its turn of the century charm. A semi-circle drive fronted the home, while a central pergola was built atop the flat red-tiled roof as a third floor—an ideal setting to view the After recent restoration of the most historic home of Coronado, it retains Pacific Ocean. The smooth, cream-colored stucco façade completed the the most commanding vista on the island taking in America’s most Italian Renaissance look. The symmetrical appearance was further beautiful beach, the Coronado Islands, Point Loma, and romantic sunsets enhanced by chimneys at both ends of the home’s two adjoining wing. -

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson the Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER of EVERYTHING

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER OF EVERYTHING JACOB ADLER and ROBERT M. KAMINS Open Access edition funded by the National En- dowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Inter- national (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non- commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copy- righted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824883669 (PDF) 9780824883676 (EPUB) This version created: 5 September, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1986 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Thelma C. Adler and Shirley R. Kamins In Phaethon’s Chariot … HAETHON, mortal child of the Sun God, was not believed by his Pcompanions when he boasted of his supernal origin. He en- treated Helios to acknowledge him by allowing him to drive the fiery chariot of the Sun across the sky. Against his better judg- ment, the father was persuaded. The boy proudly mounted the solar car, grasped the reins, and set the mighty horses leaping up into the eastern heavens. For a few ecstatic moments Phaethon was the Lord of the Sky. -

Spreckels Organ Legacy Opportunity

The 29th Annual International Summer Organ Festival Celebrating the Lives and Spirit of Vivian and Ole Evenson Concert Programs and Artists Date Artist Page June 27 Robert Plimpton 14 Marine Band San Diego July 4 Dave Wickerham 16 July 11 Christoph Bull 18 July 18 Daryl Robinson 21 July 25 Alison Luedecke 22 The Millennia Consort August 1 Kevin Bowyer 25 August 8 * Justin Bischof 28 August 15 Rising Stars: David Ball 32 ATOS Guest Organist Andrew Konopak Suzy Webster August 22 Movie Night: The General 37 Tom Trenney August 29 * Carol Williams 41 Aaron David Miller * Concert includes live video projection of the artist’s performance The Spreckels Organ Society gratefully acknowledges the major bequest of Warren M. Nichols, who wished to ensure the continuance of the Summer Organ Festival. Graphic Layout: Ross Porter / Printed by: Print Diego Cover Photo: Robert Lang 1 SPRECKELS ORGAN SOCIETY 1549 El Prado, Suite 10, San Diego CA 92101-1661 (619) 702-8138 / [email protected] www.SpreckelsOrgan.org MISSION The Spreckels Organ Society is a 501(c)3 non-profit founded in 1988 to preserve, program, and promote the Spreckels Organ as a world treasure for all people. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dr. Carol Williams—San Diego Civic Organist EXECUTIVE BOARD President - Jack Lasher Vice President - Dang Nguyen Treasurer - Clifford McMillan Secretary - Jean Samuels TRUSTEES Kris Abels Max Nanis Mitch Beauchamp David Nesvig Andrea Card Marion Persons Joseph DeMers Will Pierce Len Filomeo Lynn Reaser Dennis Fox Paulette Rodgers-Leahy Richard Griswold Paul Saunders Charles Gunther Spencer Scott Pamela Hartwell Barbara Truglio Ralph Hughes Tony Uribe Jared Jacobsen Tony Valencia Sean Jones Thomas Warschauer EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Lyle Blackinton—Curator Emeritus Ross Porter—Executive Director Dale Sorenson—Curator KEY VOLUNTEER POSITIONS Volunteer Coordinator – Andrea Card Photography – Bob Lang, Mike Cox Lighting – Roy Attridge, Len Filomeo, Dale Sorenson Sound—Steve Hall, Jordan White Sponsorship Coordinator—Ronald De Fields 2 From the President.. -

Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Balboa Park Cultural Partnership Contact: Michael Warburton [email protected] Mobile (619) 850-4677 Website: Explorer.balboapark.org Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend San Diego, CA – March 31 – The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP) announced that today the parkwide Balboa Park Explorer Pass program has resumed the sale of day and annual passes, in advance of more museums reopening this Easter weekend and beyond. “The Explorer Pass is the easiest way to visit multiple museums in Balboa Park, and is a great value when compared to purchasing admission separately,” said Kristen Mihalko, Director of Operations for BPCP. “With more museums reopening this Friday, we felt it was a great time to restart the program and provide the pass for visitors to the Park.” Starting this Friday, April 2nd, the nonprofit museums available to visit with the Explorer Pass include: • Centro Cultural de la Raza, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • Japanese Friendship Garden, 7 days/week • San Diego Air and Space Museum, 7 days/week • San Diego Automotive Museum, 6 days/week, closed Monday • San Diego Model Railroad Museum, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • San Diego Museum of Art, 6 days/week, closed Wednesdays • San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat), 5 days/week, closed Wednesday and Thursday The Fleet Science Center will rejoin the line up on April 9th; the Museum of Photographic Arts and the San Diego History Center will reopen on April 16th, and the Museum of Us will reopen on April 21st. -

Casa Del Prado in Balboa Park

Chapter 19 HISTORY OF THE CASA DEL PRADO IN BALBOA PARK Of buildings remaining from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, exhibit buildings north of El Prado in the agricultural section survived for many years. They were eventually absorbed by the San Diego Zoo. Buildings south of El Prado were gone by 1933, except for the New Mexico and Kansas Buildings. These survive today as the Balboa Park Club and the House of Italy. This left intact the Spanish-Colonial complex along El Prado, the main east-west avenue that separated north from south sections The Sacramento Valley Building, at the head of the Plaza de Panama in the approximate center of El Prado, was demolished in 1923 to make way for the Fine Arts Gallery. The Southern California Counties Building burned down in 1925. The San Joaquin Valley and the Kern-Tulare Counties Building, on the promenade south of the Plaza de Panama, were torn down in 1933. When the Science and Education and Home Economy buildings were razed in 1962, the only 1915 Exposition buildings on El Prado were the California Building and its annexes, the House of Charm, the House of Hospitality, the Botanical Building, the Electric Building, and the Food and Beverage Building. This paper will describe the ups and downs of the 1915 Varied Industries and Food Products Building (1935 Food and Beverage Building), today the Casa del Prado. When first conceived the Varied Industries and Food Products Building was called the Agriculture and Horticulture Building. The name was changed to conform to exhibits inside the building. -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS. -

Page 14 Street, Hudson, 715-386-8409 (3/16W)

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2010 ATOS NovDec 52-6 H.indd 1 10/14/10 7:08 PM ANNOUNCING A NEW DVD TEACHING TOOL Do you sit at a theatre organ confused by the stoprail? Do you know it’s better to leave the 8' Tibia OUT of the left hand? Stumped by how to add more to your intros and endings? John Ferguson and Friends The Art of Playing Theatre Organ Learn about arranging, registration, intros and endings. From the simple basics all the way to the Circle of 5ths. Artist instructors — Allen Organ artists Jonas Nordwall, Lyn Order now and recieve Larsen, Jelani Eddington and special guest Simon Gledhill. a special bonus DVD! Allen artist Walt Strony will produce a special DVD lesson based on YOUR questions and topics! (Strony DVD ships separately in 2011.) Jonas Nordwall Lyn Larsen Jelani Eddington Simon Gledhill Recorded at Octave Hall at the Allen Organ headquarters in Macungie, Pennsylvania on the 4-manual STR-4 theatre organ and the 3-manual LL324Q theatre organ. More than 5-1/2 hours of valuable information — a value of over $300. These are lessons you can play over and over again to enhance your ability to play the theatre organ. It’s just like having these five great artists teaching right in your living room! Four-DVD package plus a bonus DVD from five of the world’s greatest players! Yours for just $149 plus $7 shipping. Order now using the insert or Marketplace order form in this issue. Order by December 7th to receive in time for Christmas! ATOS NovDec 52-6 H.indd 2 10/14/10 7:08 PM THEATRE ORGAN NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2010 Volume 52 | Number 6 Macy’s Grand Court organ FEATURES DEPARTMENTS My First Convention: 4 Vox Humana Trevor Dodd 12 4 Ciphers Amateur Theatre 13 Organist Winner 5 President’s Message ATOS Summer 6 Directors’ Corner Youth Camp 14 7 Vox Pops London’s Musical 8 News & Notes Museum On the Cover: The former Lowell 20 Ayars Wurlitzer, now in Greek Hall, 10 Professional Perspectives Macy’s Center City, Philadelphia. -

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival Into Balboa Park

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival into Balboa Park By Iris H.W. Engstrand G. Aubrey Davidson’s laudatory address to an excited crowd attending the opening of the Panama-California Exposition on January 1, 1915, gave no inkling that the Spanish Colonial architectural legacy that is so familiar to San Diegans today was ever in doubt. The buildings of this exposition have not been thrown up with the careless unconcern that characterizes a transient pleasure resort. They are part of the surroundings, with the aspect of permanence and far-seeing design...Here is pictured this happy combination of splendid temples, the story of the friars, the thrilling tale of the pioneers, the orderly conquest of commerce, coupled with the hopes of an El Dorado where life 1 can expand in this fragrant land of opportunity. G Aubrey Davidson, ca. 1915. ©SDHC #UT: 9112.1. As early as 1909, Davidson, then president of the Chamber of Commerce, had suggested that San Diego hold an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. When City Park was selected as the site in 1910, it seemed appropriate to rename the park for Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who had discovered the Pacific Ocean and claimed the Iris H. W. Engstrand, professor of history at the University of San Diego, is the author of books and articles on local history including San Diego: California’s Cornerstone; Reflections: A History of the San Diego Gas and Electric Company 1881-1991; Harley Knox; San Diego’s Mayor for the People and “The Origins of Balboa Park: A Prelude to the 1915 Exposition,” Journal of San Diego History, Summer 2010. -

Plaza De Panama

WINTER 2010 www.C100.org PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Balboa Park Alliance The Committee of One Hundred, The Balboa Park Trust at the San Diego Foundation, and Friends of Balboa Park share a common goal: to protect, preserve, and enhance Balboa Park. These three non-profi t organizations have formed Our Annual Appeal Help restore the Plaza de Panama. Make a check The Balboa Park Alliance (BPAL). Functioning to The Committee of One Hundred and mail it to: as an informal umbrella organization for nonprofi t groups committed to the enhancement of the Park, THE COMMITTEE OF ONE HUNDRED BPAL seeks to: Balboa Park Administration Building 2125 Park Boulevard • Leverage public support with private funding San Diego, CA 92103-4753 • Identify new and untapped revenue streams • Cultivate and engage existing donors has great potential. That partnership must have the • Attract new donors and volunteers respect and trust of the community. Will the City • Increase communication about the value of Balboa grant it suffi cient authority? Will the public have the Park to a broader public confi dence to support it fi nancially? • Encourage more streamlined delivery of services to The 2015 Centennial of the Panama-California the Park and effective project management Exposition is only fi ve years away. The legacy of • Advocate with one voice to the City and other that fi rst Exposition remains largely in evidence: authorizing agencies about the needs of the Park the Cabrillo Bridge and El Prado, the wonderful • Provide a forum for other Balboa Park support California Building, reconstructed Spanish Colonial groups to work together and leverage resources buildings, the Spreckels Organ Pavilion, the Botanical Building, and several institutions. -

The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W

The Journal of San Diego History SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Winter 1990, Volume 36, Number 1 Thomas L. Scharf, Editor The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W. Amero Researcher and Writer on the history of Balboa Park Images from this article On July 9, 1901, G. Aubrey Davidson, founder of the Southern Trust and Commerce Bank and Commerce Bank and president of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, said San Diego should stage an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal. He told his fellow Chamber of Commerce members that San Diego would be the first American port of call north of the Panama Canal on the Pacific Coast. An exposition would call attention to the city and bolster an economy still shaky from the Wall Street panic of 1907. The Chamber of Commerce authorized Davidson to appoint a committee to look into his idea.1 Because the idea began with him, Davidson is called "the father of the exposition."2 On September 3, 1909, a special Chamber of Commerce committee formed the Panama- California Exposition Company and sent articles of incorporation to the Secretary of State in Sacramento.3 In 1910 San Diego had a population of 39,578, San Diego County 61,665, Los Angeles 319,198 and San Francisco 416,912. San Diego's meager population, the smallest of any city ever to attempt holding an international exposition, testifies to the city's extraordinary pluck and vitality.4 The Board of Directors of the Panama-California Exposition Company, on September 10, 1909, elected Ulysses S. -

Biographies of Established Masters

Biographies of Established Masters Historical Resources Board Jennifer Feeley Tricia Olsen, MCP Ricki Siegel Ginger Weatherford, MPS Historical Resources Board Staff 2011 i Master Architects Frank Allen Lincoln Rodgers George Adrian Applegarth Lloyd Ruocco Franklin Burnham Charles Salyers Comstock and Trotshe Rudolph Schindler C. E. Decker Thomas Shepherd Homer Delawie Edward Sibbert Edward Depew John Siebert Roy Drew George S. Spohr Russell Forester * John B. Stannard Ralph L. Frank Frank Stevenson George Gans Edgar V. Ullrich Irving Gill * Emmor Brooke Weaver Louis Gill William Wheeler Samuel Hamill Carleton Winslow William Sterling Hebbard John Lloyd Wright Henry H. Hester Eugene Hoffman Frank Hope, Sr. Frank L. Hope Jr. Clyde Hufbauer Herbert Jackson William Templeton Johnson Walter Keller Henry J. Lange Ilton E. Loveless Herbert Mann Norman Marsh Clifford May Wayne McAllister Kenneth McDonald, Jr. Frank Mead Robert Mosher Dale Naegle Richard Joseph Neutra O’Brien Brothers Herbert E. Palmer John & Donald B. Parkinson Wilbur D. Peugh Henry Harms Preibisius Quayle Brothers (Charles & Edward Quayle) Richard S. Requa Lilian Jenette Rice Sim Bruce Richards i Master Builders Juan Bandini Philip Barber Brawner and Hunter Carter Construction Company William Heath Davis The Dennstedt Building Company (Albert Lorenzo & Aaron Edward Dennstedt) David O. Dryden Jose Antonio Estudillo Allen H. Hilton Morris Irvin Fred Jarboe Arthur E. Keyes Juan Manuel Machado Archibald McCorkle Martin V. Melhorn Includes: Alberta Security Company & Bay City Construction Company William B. Melhorn Includes: Melhorn Construction Company Orville U. Miracle Lester Olmstead Pacific Building Company Pear Pearson of Pearson Construction Company Miguel de Pedroena, Jr. William Reed Nathan Rigdon R.P.