Universi^ Micrdrilms International Griffith, James John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Digital Booklet

1 MAIN TITLE 2 THE SMOKING FROG 3 BEDTIME AT BLYE HOUSE 4 NEW CLOTHES FOR QUINT 5 THE CHILDREN'S HOUR 6 PAS DE DEUX 7 LIKE A CHICKEN ON A SPIT 8 ALL THAT PAIN 9 SUMMER ROWING 10 QUINT HAS A KITE 11 PUB PIANO 12 ACT TWO PRELUDE: MYLES IN THE AIR 13 UPSIDE DOWN TURTLE 14 AN ARROW FOR MRS. GROSE 15 FLORA AND MISS JESSEL 16 TEA IN THE TREE 17 THE FLOWER BATH 18 PIG STY 19 MOVING DAY 20 THE BIG SWIM 21 THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS 22 BURNING DOLLS 23 EXIT PETER QUINT, ENTER THE NEW GOVERNESS; RECAPITULATION AND POSTLUDE MUSIC COMPOSED AND CONDUCTED BY JERRY FIELDING WE DISCOVER WHAT When Marlon Brando arrived in THE NIGHTCOMERS had allegedly come HAPPENED TO THE Cambridgeshire, England, during January into being because Michael Winner wanted to of 1971, his career literally hung in the direct “an art film.” Michael Hastings, a well- GARDENER PETER QUINT balance. Deemed uninsurable, too troubled known London playwright, had constructed a and difficult to work with, the actor had run kind of “prequel” to Henry James’ famous novel, AND THE GOVERNESS out of pictures, steam, and advocates. A The Turn of the Screw, which had been filmed couple of months earlier he had informed in 1961, splendidly, as THE INNOCENTS. MARGARET JESSEL author Mario Puzo in a phone conversation In Hastings’ new story, we discover what that he was all washed up, that no one was happened to the gardener Peter Quint and going to hire him again, least of all to play the governess Margaret Jessel: specifically Don Corleone in the upcoming film version how they influenced the two evil children, of Puzo’s runaway best-seller, The Godfather. -

Hamptons Doc Fest 2020 Congratulations on 13 Years of Championing Documentary Films!

Art: Nofa Aji Zatmiko ALL DOCS ALL DAY DOCS ALL ALL OPENING NIGHT FILM: MLK/FBI Hamptons Doc Fest DECEMBER 4–13, 2020 www.hamptonsdocfest.com is a year we will long Wiseman and his newest film, City Hall. 2020 rememberWELCOME or want LETTER to He stands as one of the documentary forget. Deprived of a movie theater’s giants that every aspiring filmmaker magic we struggled to take the virtual learns from, that Wiseman way of plunge. Ultimately, we decided on yes observing life unfold. Our Award films we can to bring you our 13th festival capture the essence of Art & Music, in these overwhelming times. We Human Rights, and the Environment. programmed 35 great documentary Our Opening night film reveals a hidden films to watch in the warmth and chapter in Martin Luther King’s world. comfort of your home over 10 days. No New this year, you’ll hear and see UP worries about weather, parking, ticket CLOSE video clips presented by the lines, where to catch a snack between Directors of each film. My thanks to an films. You can schedule your own day extraordinary team, and to our Artistic the way you like it. Consider it not Director, Karen Arikian. Lastly, you will only a festival experience but a virtual find all the information and help you’ll festival experiment. need to watch films on your television, When Covid hit, Hamptons Doc Fest tablet or computer. So click on and went into overdrive. We were forced step into the big virtual world wherever to cancel our Docs Equinox Spring you are. -

Rape and the Virgin Spring Abstract

Silence and Fury: Rape and The Virgin Spring Alexandra Heller-Nicholas Abstract This article is a reconsideration of The Virgin Spring that focuses upon the rape at the centre of the film’s action, despite the film’s surface attempts to marginalise all but its narrative functionality. While the deployment of this rape supports critical observations that rape on-screen commonly underscores the seriousness of broader thematic concerns, it is argued that the visceral impact of this brutal scene actively undermines its narrative intent. No matter how central the journey of the vengeful father’s mission from vengeance to redemption is to the story, this ultimately pales next to the shocking impact of the rape and murder of the girl herself. James R. Alexander identifies Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring as “the basic template” for the contemporary rape-revenge film[1 ], and despite spawning a vast range of imitations[2 ], the film stands as a major entry in the canon of European art cinema. Yet while the sumptuous black and white cinematography of long-time Bergman collaborator Sven Nykvist combined with lead actor Max von Sydow’s trademark icy sobriety to garner it the Academy Award for Best Foreign film in 1960, even fifty years later the film’s representation of the rape and murder of a young girl remain shocking. The film evokes a range of issues that have been critically debated: What is its placement in a more general auteurist treatment of Bergman? What is its influence on later rape-revenge films? How does it fit into a broader understanding of Swedish national cinema, or European art film in general? But while the film hinges around the rape and murder, that act more often than not is of critical interest only in how it functions in these more dominant debates. -

Invented Worlds

THE WIZARD OF OZ 1939, Victor Fleming Invented Worlds > This beloved classic hails from the peak of Hollywood’s Golden Age, 1939, and By Steve Chagollan was directed by the no-nonsense Victor Fleming—who also helmed Gone With the Wind, released that same year. The film’s blend of realism and fantasy is still OLLYWOOD HAS OFTEN been referred to as a fantasy striking to this day, especially the transition from Dorothy’s sepia-toned Kansas to the factory—a place where both reality and make-believe Technicolor brilliance of Oz. Sixty-five sets were constructed over six sound stages are plumbed from the vast recesses of the filmmakers’ at MGM for the effort, and the quest for perfection was so arduous it took the art imaginations. But when directors delve into literal fantasy department a week to settle on the proper and futurism, that imagination is allowed to run truly wild. shade of yellow for the Yellow Brick Road. Fleming told the film’s producer, Mervyn There have been countless milestones over the years that LeRoy, that he wanted to make “a picture that searched for beauty and decency and point to the medium’s ability to transport us to worlds that love in the world.” H only exist in the movies; here are a few choice examples. 68 DGA QUARTERLY PHOTOS: (ABOVE) AMPAS; (RIGHT) PHOTOFEST DGA QUARTERLY 69 BLADE RUNNER (1982), Ridley Scott > It’s hard to believe we’ve caught up with the time frame, 2019, in which Ridley Scott transformed Los Angeles into what he termed a near-future, “mul- tinational megalopolis,” where a rogue group of synthetic humans, known as replicants, are tracked down by a world-weary cop played by Harrison FORBIDDEN Ford. -

1 the Work of an Invisible Body: the Contribution of Foley Artists to On

1 The Work of an Invisible Body: The Contribution of Foley Artists to On-Screen Effort Lucy Fife Donaldson, University of Reading Abstract: On-screen bodies are central to our engagement with film. As sensory film theory seeks to remind us, this engagement is sensuous and embodied: our physicality forms sympathetic, kinetic and empathetic responses to the bodies we see and hear. We see a body jump, run and crash and in response we tense, twitch and flinch. But whose effort are we responding to? The character’s? The actor’s? This article explores the contribution of an invisible body in shaping our responsiveness to on-screen effort, that of the foley artist. Foley artists recreate a range of sounds made by the body, including footsteps, breath, face punches, falls, and the sound clothing makes as actors walk or run. Foley is a functional element of the filmmaking process, yet accounts of foley work note the creativity involved in these performances, which add to characterisation and expressivity. Drawing on detailed analysis of sequences in Cabaret (Bob Fosse, 1972) and Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988) which foreground exertion and kinetic movement through dance and physical action, this article considers the affective contribution of foley to the physical work depicted on-screen. In doing so, I seek to highlight the extent to which foley constitutes an expressive performance that furthers our sensuous perception and appreciation of film. On-screen bodies are central to our engagement with film; the ways they are framed and captured by the camera guides our attention to character and action, while their physical qualities invite a range of engagement from admiration, appreciation and desire to awe, fear and repugnance. -

Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm

JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 3 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm Edited by Cristina M. Giannantonio Amy E. Hurley-Hanson Associate Professors of Management, George L. Argyros School of Business and Economics, Chapman University, USA NEW HORIZONS IN LEADERSHIP STUDIES Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 4 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 © Cristina M. Giannantonio andAmy E. Hurley-Hanson 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited The Lypiatts 15 Lansdown Road Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. William Pratt House 9 Dewey Court Northampton Massachusetts 01060 USA A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946802 This book is available electronically in the ElgarOnline.com Business Subject Collection, E-ISBN 978 1 78100 212 4 ISBN 978 1 78100 211 7 (cased) Typeset by Columns Design XML Ltd, Reading Printed and bound in Great Britain by T.J. International Ltd, Padstow Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 2 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 1 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:57:46 2013 14. Extreme leadership as creative leadership: reflections on Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather Charalampos Mainemelis and Olga Epitropaki INTRODUCTION How do extreme leadership situations arise? According to one view, they are triggered by environmental factors that have nothing or little to do with the leader. -

![[ Captioner Standing by ] 1 >> the Broadcast Is Now Starting. All Attendees Are in Listen-Only Mode. >> JESSIE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4385/captioner-standing-by-1-the-broadcast-is-now-starting-all-attendees-are-in-listen-only-mode-jessie-194385.webp)

[ Captioner Standing by ] 1 >> the Broadcast Is Now Starting. All Attendees Are in Listen-Only Mode. >> JESSIE

[ Captioner standing by ] 1 >> The broadcast is now starting. All attendees are in listen-only mode. >> JESSIE: Hello, everyone. Welcome to today's Webinar Understanding Chemsex Essentials for Testing the Addictive Fusion of Drug and Sex. It's so great that you could be with us here. I'm Jessica O'Brien. I will be the facilitator. Make sure to bookmark this page so you can stay up to date on all of the latest in addiction education. Closed captioning is provided by CaptionAccess. You will notice the Go-To Webinar. You can use the orange arrow at any point to minimize or maximize the menu and you can just move it out of the way if that's what is best for you. I will bring your attention to the questions box. We're going to gather any questions for our presenter today in the questions box and then ask him during the Q&A session at the -- towards the end of the presentation. So if you have any questions for Dr. Fawcett, feel free to right those in the Q&A box. Also, we have -- bringing your attention to the handouts tab. You can find a copy of the slides for today's presentation as well as a user-friendly instructional guide on how to access our online CE quiz and immediately earn your certificate. If you have never gotten a certificate from us before, make sure you use the instructions in our handout tab when you are ready to take the quiz. Every NAADAC Webinar has its own web page that houses everything that you need to know about that 2 particular Webinar. -

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

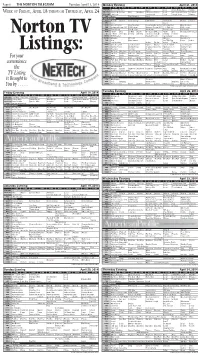

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

![[Michael] Winner Luc Chaput](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6245/michael-winner-luc-chaput-206245.webp)

[Michael] Winner Luc Chaput

Document generated on 09/30/2021 3:14 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma [Gerry] Anderson ... [Michael] Winner Luc Chaput Number 283, March–April 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/68696ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Chaput, L. (2013). [Gerry] Anderson ... [Michael] Winner. Séquences, (283), 20–21. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 20 PANORAMIQUE | Salut l'artiste [GERRY] ANDERSON ... [MICHAEL] WINNER Gerry Anderson | 1929-2012 photographie, et le mari de la comédienne Stefan Kudelski | 1929-2013 Né Gerald Alexander Abrahams, réalisa- Luce Guilbeault. Ingénieur suisse d’origine polonaise, inven- teur et producteur britannique qui, avec teur du magnétophone Nagra (il enregistrera son épouse Sylvia Thamm, créa la télésé- Harry Carey, Jr. | 1921-2012 en polonais) et de ses multiples versions rie culte Thunderbirds (Les Sentinelles de l’air). Fils d’un acteur qui était un grand ami pour lequel il reçut quatre Oscars et la mé- de John Ford, il prit part à plus de cent daille d’honneur John Grierson de la SMPTE. -

10 Tips on How to Master the Cinematic Tools And

10 TIPS ON HOW TO MASTER THE CINEMATIC TOOLS AND ENHANCE YOUR DANCE FILM - the cinematographer point of view Your skills at the service of the movement and the choreographer - understand the language of the Dance and be able to transmute it into filmic images. 1. The Subject - The Dance is the Star When you film, frame and light the Dance, the primary subject is the Dance and the related movement, not the dancers, not the scenography, not the music, just the Dance nothing else. The Dance is about movement not about positions: when you film the dance you are filming the movement not a sequence of positions and in order to completely comprehend this concept you must understand what movement is: like the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze said “w e always tend to confuse movement with traversed space…” 1. The movement is the act of traversing, when you film the Dance you film an act not an aestheticizing image of a subject. At the beginning it is difficult to understand how to film something that is abstract like the movement but with practice you will start to focus on what really matters and you will start to forget about the dancers. Movement is life and the more you can capture it the more the characters are alive therefore more real in a way that you can almost touch them, almost dance with them. The Dance is a movement with a rhythm and when you film it you have to become part of the whole rhythm, like when you add an instrument to a music composition, the vocabulary of cinema is just another layer on the whole art work. -

12Th Irish Screen Studies Seminar Dublin City University, 11 May 2016

12th Irish Screen Studies Seminar Dublin City University, 11 May 2016 A Report by Loretta Goff, University College Cork Since its inauguration in 2003, the annual Irish Screen Studies Seminar has acted as a platform for researchers in the area of film and screen cultures to share their work. The seminar is specifically aimed at postgraduate and postdoctoral scholars working out of Irish universities and colleges or with Irish topics, but covers screen culture in the broadest sense, ranging from the audio to the visual, film, television and digital media to transmedia and gaming. This diversity of topic was reflected at the 12th Irish Screen Studies Seminar, which was a one-day event featuring four panels and a keynote address by Catherine Grant (Sussex). The day began with the “Screen: Migration, Policy, and Practice” panel, including papers addressing each of the panel’s subheadings, with a particular theme of transmediality running throughout them. Cormac Mc Garry (NUI Galway) addressed the topic of media migration with his paper titled “Comic Books in the Digital Age: The Great Screen Migration?”, where he explained transmedia approaches to comics in association with the horizontal integration of media conglomerates. The “big two” comics producers, Marvel and DC, are subsidiaries of Disney and Time Warner respectively, who have slated comic film release dates as far in advance as 2020, and who simultaneously produce games, TV shows and even motion and Guided View comics across their various subsidiaries to reinforce viewer commitments across channels. Maria O’Brien (Dublin City University) then shed some light on tax incentive policies (or lack thereof) for video game production, as compared to film, in her paper “Video Games in the 2013 Cinema Communication Negotiations: A Political Economic Perspective”. -

108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: the Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film

Premiere of Dark Command, Lawrence, 1940. Courtesy of the Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History, Lawrence, Kansas. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 38 (Summer 2015): 108–135 108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: The Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film edited and introduced by Thomas Prasch ut the great fact was the land itself which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes. It was from facing this vast hardness that the boy’s mouth had become so “ bitter; because he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness” (Willa Cather, O Pioneers! [1913], p. 15): so the young boy Emil, looking out at twilight from the wagon that bears him backB to his homestead, sees the prairie landscape with which his family, like all the pioneers scattered in its vastness, must grapple. And in that contest between humanity and land, the land often triumphed, driving would-be settlers off, or into madness. Indeed, madness haunts the pages of Cather’s tale, from the quirks of “Crazy Ivar” to the insanity that leads Frank Shabata down the road to murder and prison. “Prairie madness”: the idea haunts the literature and memoirs of the early Great Plains settlers, returns with a vengeance during the Dust Bowl 1930s, and surfaces with striking regularity even in recent writing of and about the plains.