An Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Randomised Controlled Trial Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Intramuscular Injection Is an Injection Given Directly Into The

Depo Lupron and Testosterone are both given by intramuscular injection. The following is a guideline on their administration. Eileen Durham, RN, NP Version 12 Jan 2010 Description Intramuscular (IM) injections are given directly into the central area of selected muscles. There are a number of sites that are suitable for IM injections; there are three sites that are most commonly used in this procedure described below. The volume of viscosity of the medication to be injected determines the site that should be used. IM injections cause stretching of the muscle fiber so the larger the muscle used the less discomfort. Intramuscular Injection Sites Depo Lupron Depo Lupron 3 month preparation should only be injected into the Gluteus medius due to the viscosity and volume of the medication approx. 1.5 – 2 cc. Depo Lupron 1 month preparation can be injection into the vastus lateralis or the gluteus medius. Testosterone Testosterone administered to adolescents and adults can be injected into any of the sites listed below, as long as the volume is 1 cc or less. For a volume of 1.5 use the vastus lateralis or Gluteus medius, if the volume is 2 cc you must you the largest muscle the Gluteus medius. If the volume is greater then 2 cc you must divide the dose and give 2 injections as the maximum volume in the Gluteal muscle is 2 cc. Testosterone administered to infants and toddlers use only the anteriolateral aspect of the thigh. Deltoid muscle The deltoid muscle located laterally on the upper arm can be used for intramuscular injections. -

Injection Technique 1: Administering Drugs Via the Intramuscular Route

Copyright EMAP Publishing 2018 This article is not for distribution except for journal club use Clinical Practice Keywords Intramuscular injection/ Medicine administration/Absorption Practical procedures This article has been Injection technique double-blind peer reviewed Injection technique 1: administering drugs via the intramuscular route rugs administered by the intra- concerns that nurses are still performing Author Eileen Shepherd is clinical editor muscular (IM) route are depos- outdated and ritualistic practice relating to at Nursing Times. ited into vascular muscle site selection, aspirating back on the syringe Dtissue, which allows for rapid (Greenway, 2014) and skin cleansing. Abstract The intramuscular route allows absorption into the circulation (Dough- for rapid absorption of drugs into the erty and Lister, 2015; Ogston-Tuck, 2014). Site selection circulation. Using the correct injection Complications of poorly performed IM Four muscle sites are recommended for IM technique and selecting the correct site injection include: administration: will minimise the risk of complications. l Pain – strategies to reduce this are l Vastus lateris; outlined in Box 1; l Rectus femoris Citation Shepherd E (2018) Injection l Bleeding; l Deltoid; technique 1: administering drugs via l Abscess formation; l Ventrogluteal (Fig 1, Table 1). the intramuscular route. Nursing Times l Cellulitis; Traditionally the dorsogluteal (DG) [online]; 114: 8, 23-25. l Muscle fibrosis; muscle was used for IM injections but this l Injuries to nerves and blood vessels muscle is in close proximity to a major (Small, 2004); blood vessel and nerves, with sciatic nerve l Inadvertent intravenous (IV) access. injury a recognised complication (Small, These complications can be avoided if 2004). -

Self-Administering a Vitamin B12 Injection

Self-administering a Vitamin B12 injection This is usually given as an intramuscular injection, every 2-3 months. Alternatives to an intramuscular injection are: Oral Vitamin B12 at a dose of at least 1000mcg per day. • Available as tablets or a spray. They can be bought over the counter and available at most health food stores and pharmacies. • Oral Vitamin B12 is not recommended if: - If you have a bowel condition such as inflammatory bowel disease, Coeliac disease, small bowel overgrowth, bile acid malabsorption and short bowel (you will require injections) - You require an initial loading of B12 (soon after diagnosis) It is important to monitor your symptoms if you change to oral B12. If symptoms return, then the oral/sublingual dose can be increased to 2000mcg or you may need to consider starting back on injections. https://www.hollandandbarrett.com/shop/product/betteryou-pure-energy-b12-boost-oral-spray-60099160?skuid=099160 https://www.hollandandbarrett.com/search?query=%20Vitamin%20B12%20Tablets&utm_medium=cpc&utm_source=google&isSearch=true# gclid=EAIaIQobChMIh5nLgOH26AIVxLTtCh0JIA_GEAAYASAAEgJL-fD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds Subcutaneous (SC) injection; this is off-licence but still effective. It is considered an easier method of administration. It is how insulin and blood thinning medication are usually self-administered. Equipment needed to self-inject - Prescribed medicine - 1 syringe (2 ml) - 2 needles (1 for drawing up the drug and 1 for administration – you can use the same size needle for both). o For an IM injection; the needle gauge should be 19-25. The needle length is 1- 1 ½ inches (up to 3 inches for larger adults) o For a SC injection; the needle gauge should be 25-27. -

Efficacy/Risk Profile of Triamcinolone Acetonide in Severe Asthma

ARTICLE IN PRESS Respiratory Medicine CME (2008) 1, 111–115 respiratory MEDICINE CME CASE REPORT Efficacy/risk profile of triamcinolone acetonide in severe asthma: Lessons from one case study Cesar Picadoà Servei de Pneumologia, Hospital Clinic, Universitat de Barcelona, Villarroel 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain Received 26 November 2007; accepted 22 January 2008 KEYWORDS Summary Insulin; Some prednisone-resistant asthma patients respond to intramuscular triamcinolone Refractory asthma; acetonide (TA). The use of TA has been questioned on the basis of its potential toxicity. Severe asthma; TA’s ratio of clinical efficacy to systemic effects compared with oral prednisone has not Steroid-dependent been clearly defined. asthma; We report the case of a prednisone-insensitive severe asthma patient with insulin- Triamcinolone dependent diabetes, hypertension and diabetic retinopathy treated with repeated sessions acetonide of laser therapy. By daily monitoring the needs of insulin doses we compared the systemic effects of prednisone and TA. The analysis of the balance between systemic effects (insulin doses) and beneficial effects (PEF values) show that TA has a better benefit/risk profile than prednisone. The patient has been followed up for 3 years and has received injections of TA repeated at intervals ranging from 21 to 60 days according to patient response and the evolution of PEF and clinical symptoms. During this period the patient lost 3 kg of weight, while presenting increased bone mineral density, normalized arterial tension, and improved proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The present case report shows that TA has a better benefit/risk profile than prednisone. TA can be a valuable alternative in the control of some patients with severe prednisone- resistant asthma. -

How to Administer Intramuscular, Intradermal, and Intranasal Influenza Vaccines

How to Administer Intramuscular, Intradermal, and Intranasal Influenza Vaccines Intramuscular injection (IM) Intradermal administration (ID) Intranasal administration (NAS) Inactivated Influenza Vaccines (IIV), including Inactivated Influenza Vaccine (IIV) Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine (LAIV) recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3) 1 Gently shake the microinjection system before 1 FluMist (LAIV) is for intranasal administration 1 Use a needle long enough to reach deep into administering the vaccine. only. Do not inject FluMist. the muscle. Infants age 6 through 11 mos: 1"; 1 through 2 yrs: 1–1¼"; children and adults 2 Hold the system by placing the 2 Remove rubber tip protector. Do not remove 3 yrs and older: 1–1½". thumb and middle finger on dose-divider clip at the other end of the sprayer. the finger pads; the index finger 2 With your left hand*, bunch up the muscle. should remain free. 3 With the patient in an upright position, place the tip just inside the nostril 3 With your right hand*, insert the needle at a 3 Insert the needle perpendicular to the skin, to ensure LAIV is delivered into 90° angle to the skin with a quick thrust. in the region of the deltoid, in a short, quick the nose. The patient should movement. breathe normally. 4 Push down on the plunger and inject the entire contents of the syringe. There is no need to 4 Once the needle has been 4 With a single motion, depress plunger as aspirate. inserted, maintain light pressure rapidly as possible until the dose-divider clip on the surface of the skin and prevents you from going further. -

Intramuscular Injections: GUIDELINES for BEST PRACTICE B

2.1 ANCC Contact Hours Abstract The administration of injec- tions is a fundamental nursing skill; however, it is not without risk. Children receive numer- ous vaccines, and pediatric nurses administer the major- ity of these vaccines via the intramuscular route, and thus must be knowledgeable about safe and evidence-based immunization programs. Nurses may not be aware of the potential consequences associated with poor injection practices, and historically have relied on their basic nursing training or the advice of colleagues as a substitute for newer evidence about how to administer injections today. Evidence-based nursing practice requires pediatric nurses to review current literature to establish best practices and thus improved patient outcomes. Key words: Child; Evidence-based nursing; Injection intramuscu- lar; Vaccination. AbbyPediatric Rishovd, DNP, PNP Intramuscular Injections: GUIDELINES FOR BEST PRACTICE B. Boissonnet / BSIP SA / Alamy Alamy / B. Boissonnet / BSIP SA March/April 2014 MCN 107 Copyright © 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. ver the past decade, the childhood vaccine (2011), and the World Health Organization (2004) have schedule has increased in complexity. De- now all strongly discouraged the practice of aspirating for pending upon the combinations adminis- blood when administering an IM injection. A randomized tered, children now may receive as many control trial found that the standard injection technique as 24 immunizations via intramuscular consisting of slow aspiration and injection followed by O(IM) injection by 2 years of age (Centers withdrawal of the needle was more painful and took lon- for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011). Pedi- ger than rapid injection without aspiration (Ipp, Taddio, atric nurses administer the majority of injections and thus Sam, Gladbach, & Parkin, 2007). -

Self-Administering an Intramuscular Injection

Self-administering an Intramuscular injection If you have testosterone injections: - You can consider self-injecting Sustanon. - We do not recommend self-administration of Nebido as this is a more difficult to give (due to the high viscosity and preferred site of administration). If you wish to switch from Nebido to Sustanon, so you can self-inject, we will get advice from your GIC - A change to testosterone gel is an option. If this is something you wish to consider then please discuss with your GIC or a medical professional at the Health Centre. Equipment needed for an IM injection - Prescribed medicine - 1 syringe - 2 needles (1 for drawing up the drug and 1 for administration – you can use the same size needle for both) - Sharps box (purple lid for testosterone injections and yellow lid for everything else) Below is a list of the syringes and needle sizes required. If you are injecting a drug not listed below then please contact the Health Centre for further advice. These can be purchased online without a prescription. This is normally the most cost-effective way; Amazon have a good stock. If you have any problems purchasing equipment please contact the Health Centre. There is no need to purchase alcohol wipes. PHE (2013) advised that if you are physically clean and in good general health then swabbing prior to injecting is not required. Drug Syringe Size Needle Gauge Needle Length Site Angle 1- 1½ inches (up Testosterone Thigh, upper 2ml 19-25 to 3 inches for 90 (Sustanon) arm, buttocks larger adults) 1-1 ½ inches (up Thigh, upper B12 (IM) 2ml 19-25 to 3 inches for 90 arm, buttocks larger adults) Comes preloaded with 2 syringes, one MMR Thigh 90 for drawing up and one for injecting Where to inject The easiest site when self-administering an IM injection is the middle third of the vastus lateralis muscle of the thigh. -

Injection Guide Overview and Goals of This Guide ����������������������������������� 1

Injection Guide Overview and goals of this guide . 1 Overview of injections. 3 Why did my doctor choose an injectable medication? ��������������� 3 Differences between injectable medication and oral medication . 3 Types of injections. 4 Parts of a syringe ��������������������������������������������������� 4 Steps for injecting medication ��������������������������������������� 5 Storage ������������������������������������������������������������� 5 Preparation ��������������������������������������������������������� 6 Wash your hands ����������������������������������������������� 6 Prepare your medication for injection ��������������������������� 7 Prepare the injection site ��������������������������������������� 8 Injection ����������������������������������������������������������� 9 Intramuscular injection ����������������������������������������� 9 Subcutaneous injection ����������������������������������������10 Disposal. .11 Monitoring of the injection site ����������������������������� 12 References . .13 Injection-site records ������������������������������������������������14 Overview and goals of this guide This guide is a quick reference on how to use medications that are given by injection. It gives step-by-step instructions for preparing and injecting the medication. It also covers safety precautions. The instructions in this guide apply whether you are giving the injection to someone you care for or you are giving the injection to yourself. This guide is not meant to replace instructions from your doctor nor the information -

Intramuscular Injection

Welcome to Kaiser Permanente Southern California Student Unpaid Field Experience and Training Inpatient/Hospital and Outpatient/Ambulatory 1 Table of Contents 1 Policy: Student Unpaid Field Experience and Training- SC.QRM.PCS.026 Pg. 3 Appendix A. Onboarding Process 2 Policy: Drug-Free Workplace- NATL.HR.030 Pg. 13 3 Principles of Responsibility (Compliance) Respect Confidentiality, Privacy, and Security Pg. 20 Focus Resources on Member and Patient Care Protect Our Assets and Information 4 2020 Ambulatory Health Care and Hospital National Patient Safety Goals Pg. 31 5 Situation, Background, Assessment and Recommendation (SBAR) Pg. 33 6 Emergency Codes Pg. 34 Student Nurses Continue with Items 7-11 7 KP Nursing Professional Practice Model Pg. 36 8 KP Nursing Professional Practice: Nursing Vision and Values Pg. 37 9 Medication Administration Pg. 38 Policy/Practice Excerpts: Student Un-Paid Field Experience/ Regional High-Alert Medication Safety Practices Safe Medication Practices, General; Oral Drug Administration; Enteral Drug Administration; Intramuscular Injection; Subcutaneous Injection; Metered Dose Inhaler Use; IV Secondary Line Drug Infusion; Rectal suppository Administration 10 Bar Code Scanning Medication Administration- Instructions for Students Pg. 55 11 Nurse Knowledge Exchange + Pg. 56 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Appendix A 1.0 Onboarding Process 1.1 All participating Schools agree to adhere to a standardized process for Program Participant prerequisites. 1.1.1 Student/Faculty prerequisites website address: http://kpnursing.org/_SCAL/professionaldevelopment/orientation/index.html -

Large-Volume IM Injections

FEATURE | Large-volume IM injections Large-volume IM injections: A review of best practices Intramuscular injections offer improved treatment adherence, ease in monitoring of adverse effects, and multiple administration sites Una HOPKINS, RN, FNP-BC, DNP; CLaudIA Y. ARIAS, RN, OCN ntramuscular (IM) injection is one of many routes for administering medications, includ- Dorsogluteal site ing antibiotics, vaccines, hormonal therapies, I 1,2 and corticosteroids. Even when alternate routes of administration are available, IM injections may be preferred when a patient cannot tolerate oral medication or when adherence is a concern.2 IM injections also may be beneficial for absorp- tion compared with other routes of administra- tion (ie, faster than subcutaneous injection and slower than intravenous administration). In addition, some medications contain components that can irritate subcutaneous tissue but not muscle tissue, which also can tolerate larger fluid volumes with minimal discomfort.3,4 Large-volume injections (3 mL or greater), however, are not frequently administered; and many clinicians may not be familiar with their appropriate use, possible side effects, and potential efficacy. Medications administered via large- volume IM injections include ceftazidime (Fortaz, Tazicef, generics), cefuroxime (Ceftin, Zinacef, generics), ertapenem (Invanz), penicillin G ben- zathine (Bicillin L-A, Permapen), and fulvestrant (Faslodex).5-9 This article discusses the practical issues related to administration of large-volume IM injections, in the setting of administering fulvestrant for the treatment of breast cancer, with a focus on best practices for efficacy and safety. IM injections are administered in five potential © MICHELE GRAHAM sites: deltoid (commonly used for adult vac- FIGURE 1A. Potential sites for intramuscular injection: Dorsogluteal site cinations), dorsogluteal, ventrogluteal, rectus 32 ONCOLOGY NURSE ADVISOR • JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2013 • www.OncologyNurseAdvisor.com FEATURE | Large-volume IM injections femoris, and vastus lateralis3,10,11 (Figure 1). -

Needle Gauge Resource List

Needle Gauge Resource List COMMON USES FOR NEEDLE BY GAUGE SIZE Overview: There is currently no peer-reviewed research showing which needles work best in different situations. This resource comes from the Harm Reduction Coalition and Syringe Service Programs in Minnesota. The information here can serve as a starting point, but individual preferences may vary. The gauge (abbreviated as “G”) of a needle refers to the size of the hole in the needle. The higher the gauge, the smaller the hole. Needles come in various gauges and lengths. The length of a needle is listed after the gauge number. For example, 25G ½ refers to a 25 gauge, ½ inch-long needle. Longer needles (½ inch or longer) are commonly used for intramuscular injections, while shorter (shorter than ½ inch) needles are more often used for intravenous injections. Different sized needles are used for different purposes. For areas of the body with smaller veins like the hands or feet, a higher gauge needle or butterfly needle is commonly used. Please use the table below to understand what gauge needle is commonly used for different purposes (e.g., intramuscular injection, intravenous injection). Needle Gauge Resource List Needle Gauge: Needle Length: Used for: 18 1 Inch Transferring intramuscular hormones from vial to syringe 21 Intramuscular injections (e.g., naloxone, steroids, hormones) 22 ½ inch Intramuscular injections (hormones) Intramuscular injections (e.g., naloxone, steroids, hormones), 23 1 Inch methadone Intravenous drug use, intramuscular hormone administration, 25 1 Inch Intravenous crushed pills 27 ½ inch Standard insulin set, intravenous drug use 28 ½ inch Standard insulin set, intravenous drug use 29 ½ inch Intravenous drug use 5 30 ½ or /16 inch Intravenous drug use 5 31 /16 inch Intravenous drug use Minnesota Department of Health STD/HIV/TB Section 651-201-5414 www.health.state.mn.us/syringe 11/7/2019, To obtain this information in a different format, call: 651-201-5414. -

Injection Considerations for Needle Length and Gauge Selection

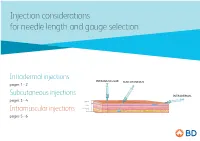

Injection considerations for needle length and gauge selection Intradermal injections INTRAMUSCULAR SUBCUTANEOUS pages 1 - 2 Subcutaneous injections INTRADERMAL pages 3 - 4 Epidermis Dermis Subcutaneous tissue Intramuscular injections Muscle pages 5 - 6 1 Intradermal injection considerations For needle length and gauge selection* INTRAMUSCULAR SUBCUTANEOUS INTRADERMAL Epidermis Dermis Subcutaneous tissue Muscle Intradermal (ID) Location of injection** Needle length** Needle gauge** Needle angle < 12 months (infants) Anterolateral aspect Paediatric of forearm, upper chest, 12 months to 18 years 10mm – 19mm 26 – 28 G º º to adult upper back, back of upper 10 – 15 arm > 18 years * Adapted from Fundamentals of Nursing Human Health and Function, Craven R, Hirnle C, Henshaw CM, 8th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2017 ** Location, needle length & gauge dependent on patient age, physical condition and medication requirements. 2 Intradermal (ID) injection considerations: .8 .7 .6 .5 .4 .3 .2 10-15° Anterior aspect of the Upper chest Injection procedure forearm • Spread the skin taut, and insert the needle tip at a 10º – 15º angle. • Inject medication slowly. If a wheal does not appear, it was administered in the subcutaneous tissue. Upper back / back of arm This information is being provided for convenience only and is not intended to replace clinical decision making. Each clinician is soley responsible for determining the correct needle for each patient. 3 Subcutaneous injection considerations For needle length and gauge selection* INTRAMUSCULAR SUBCUTANEOUS