Downloaded from Brill.Com09/25/2021 08:47:44AM Via Free Access 80 Doron and Thomas Tion,”1 Spurred a Lengthier Discussion Within out Editorial Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. the Secession of Biafra, 1967–1970

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2020-06 Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa Thomas, Charles G.; Falola, Toyin University of Calgary Press Thomas, C. G., & Falola, T. (2020). Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112216 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca SECESSION AND SEPARATIST CONFLICTS IN POSTCOLONIAL AFRICA By Charles G. Thomas and Toyin Falola ISBN 978-1-77385-127-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Ph.D Thesis-A. Omaka; Mcmaster University-History

MERCY ANGELS: THE JOINT CHURCH AID AND THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IN BIAFRA, 1967-1970 BY ARUA OKO OMAKA, BA, MA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2014), Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: Mercy Angels: The Joint Church Aid and the Humanitarian Response in Biafra, 1967-1970 AUTHOR: Arua Oko Omaka, BA (University of Nigeria), MA (University of Nigeria) SUPERVISOR: Professor Bonny Ibhawoh NUMBER OF PAGES: xi, 271 ii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 1. AJEEBR`s sponsored advertisement ..................................................................122 2. ACKBA`s sponsored advertisement ...................................................................125 3. Malnourished Biafran baby .................................................................................217 Tables 1. WCC`s sickbays and refugee camp medical support returns, November 30, 1969 .....................................................................................................................171 2. Average monthly deliveries to Uli from September 1968 to January 1970.........197 Map 1. Proposed relief delivery routes ............................................................................208 iii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ABSTRACT International humanitarian organizations played a prominent role -

Civil War 1968-1970

Copyright by Roy Samuel Doron 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Roy Samuel Doron Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Forging a Nation while losing a Country: Igbo Nationalism, Ethnicity and Propaganda in the Nigerian Civil War 1968-1970 Committee: Toyin Falola, Supervisor Okpeh Okpeh Catherine Boone Juliet Walker H.W. Brands Forging a Nation while losing a Country: Igbo Nationalism, Ethnicity and Propaganda in the Nigerian Civil War 1968-1970 by Roy Samuel Doron B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2011 Forging a Nation while losing a Country: Igbo Nationalism, Ethnicity and Propaganda in the Nigerian Civil War 1968-1970 Roy Samuel Doron, PhD The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Toyin Falola This project looks at the ways the Biafran Government maintained their war machine in spite of the hopeless situation that emerged in the summer of 1968. Ojukwu’s government looked certain to topple at the beginning of the summer of 1968, yet Biafra held on and did not capitulate until nearly two years later, on 15 January 1970. The Ojukwu regime found itself in a serious predicament; how to maintain support for a war that was increasingly costly to the Igbo people, both in military terms and in the menacing face of the starvation of the civilian population. Further, the Biafran government had to not only mobilize a global public opinion campaign against the “genocidal” campaign waged against them, but also convince the world that the only option for Igbo survival was an independent Biafra. -

Purple Hibiscus

1 A GLOSSARY OF IGBO WORDS, NAMES AND PHRASES Taken from the text: Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Appendix A: Catholic Terms Appendix B: Pidgin English Compiled & Translated for the NW School by: Eze Anamelechi March 2009 A Abuja: Capital of Nigeria—Federal capital territory modeled after Washington, D.C. (p. 132) “Abumonye n'uwa, onyekambu n'uwa”: “Am I who in the world, who am I in this life?”‖ (p. 276) Adamu: Arabic/Islamic name for Adam, and thus very popular among Muslim Hausas of northern Nigeria. (p. 103) Ade Coker: Ade (ah-DEH) Yoruba male name meaning "crown" or "royal one." Lagosians are known to adopt foreign names (i.e. Coker) Agbogho: short for Agboghobia meaning young lady, maiden (p. 64) Agwonatumbe: "The snake that strikes the tortoise" (i.e. despite the shell/shield)—the name of a masquerade at Aro festival (p. 86) Aja: "sand" or the ritual of "appeasing an oracle" (p. 143) Akamu: Pap made from corn; like English custard made from corn starch; a common and standard accompaniment to Nigerian breakfasts (p. 41) Akara: Bean cake/Pea fritters made from fried ground black-eyed pea paste. A staple Nigerian veggie burger (p. 148) Aku na efe: Aku is flying (p. 218) Aku: Aku are winged termites most common during the rainy season when they swarm; also means "wealth." Akwam ozu: Funeral/grief ritual or send-off ceremonies for the dead. (p. 203) Amaka (f): Short form of female name Chiamaka meaning "God is beautiful" (p. 78) Amaka ka?: "Amaka say?" or guess? (p. -

Growth of the Catholic Church in the Onitsha Province Op Eastern Nigeria 1905-1983 V 14

THE CONTRIBUTION OP THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OP EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 V 14 - I BY REV. FATHER VINCENT NWOSU : ! I i A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY , DEGREE (EXTERNAL), UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1988 ProQuest Number: 11015885 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015885 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 s THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OF EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 By Rev. Father Vincent NWOSU ABSTRACT Recent studies in African church historiography have increasingly shown that the generally acknowledged successful planting of Christian Churches in parts of Africa, especially the East and West, from the nineteenth century was not entirely the work of foreign missionaries alone. Africans themselves participated actively in p la n tin g , sustaining and propagating the faith. These Africans can clearly be grouped into two: first, those who were ordained ministers of the church, and secondly, the lay members. -

Newsletter Igbo Studies Association

NEWSLETTER IGBO STUDIES ASSOCIATION VOLUME 1, FALL 2014 ISSN: 2375-9720 COVER PHOTO CREDIT INCHSERVICES.COM PAGE 1 VOLUME 1, FALL 2014 EDITORIAL WELCOME TO THE FIRST EDITION OF ISA NEWS! November 2014 Dear Members, I am delighted to introduce the first edition of ISA Newsletter! I hope your semester is going well. I wish you the best for the rest of the academic year! I hope that you will enjoy this maiden issue of ISA Newsletter, which aims to keep you abreast of important issue and events concerning the association as well as our members. The current issue includes interesting articles, research reports and other activities by our Chima J Korieh, PhD members. The success of the newsletter will depend on your contributions in the forms of President, Igbo Studies Association short articles and commentaries. We will also appreciate your comments and suggestions for future issues. The ISA executive is proud to announce that a committee has been set up to work out the modalities for the establishment of an ISA book prize/award. Dr Raphael Njoku is leading the committee and we expect that the initiative will be approved at the next annual general meeting. The 13th Annual Meeting of the ISA taking place at Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is only six months away and preparations are ongoing to ensure that we have an exciting meet! We can’t wait to see you all in Milwaukee in April. This is an opportunity to submit an abstract and to participate in next year’s conference. ISA is as strong as its membership, so please remember to renew your membership and to register for the conference, if you have not already done so! Finally, we would like to congratulate the newest members of the ISA Executive who were elected at the last annual general meeting in Chicago. -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Victimization During the Nigerian Civil War: a Focus on the Asaba Massacre Nwanne W

Victimization During the Nigerian Civil War: A Focus on the Asaba Massacre Nwanne W. Okafor SEPTEMBER 2014 Master of Victimology and Criminal Justice Tilburg Law School Tilburg University Masters Thesis Supervisor: Dr M. F Ndahinda Second Reader: Dr E. Lahlah ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Writing this paper has been one of the most consequential academic tasks I have ever had to deal with. Without the support, encouragement and prayers of the following people, this study would not have been accomplished. I owe my deepest and most sincere gratitude to them. First and foremost, to God the Almighty Father - The Alpha and Omega. I thank you Lord for giving me the grace and strength to complete this wonderful academic journey. Words are not enough to express my gratitude. My family: Daddy, Mummy, Ngozi, Nkechi, Onyeabor, Ik, Nnamdi, Chiedu and my beautiful nephews and nieces- I am proud and blessed to be a part of such a dynamic dynasty. Dr. Christine Ocran and Yinka Ndah – Even though you are no longer with us, I shall continue to remain grateful for your friendship and encouragement. Continue to rest in peace. My Tilburg family: Vira, Ivan, Pauline, Tugce, Ana, Naya, Hanny, Marc and Shehzad – Thank you for such a beautiful experience. I had the best time of my life. I will definitely miss those precious times we spent together. Uncle Lanre Ogunlesi, Mr Dele Belgore, Mr Yinka Akinkugbe, Mr Asue Ighodalo and Mr E. J Williams – I am indeed grateful for everything. To my best friends: Bro. Chucks, Tinuke, Chinedum and Kamsi Adichie – thank you for your love and support. -

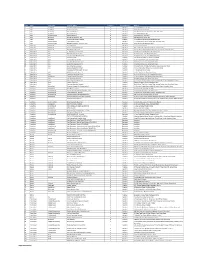

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-14078-3 — the Asaba Massacre S

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-14078-3 — The Asaba Massacre S. Elizabeth Bird , Fraser M. Ottanelli Index More Information Index Abacha, Sani, 183 and tradition of education, 24 Abagana, ambush at, 115, 116, 140 complex ethnic identity of, 25–27, Abasiekong, Dan, 84 188–189 Abudu, reported violence by Biafrans, 16 destruction of Niger Bridge at, 32–35 Aburi summit meeting, 10 effects of massacre on kinship structure, Achebe, Chinua, 169, 180 122–124, 193–194 Achuzia, Joseph, 26, 32, 58 federal troops killing civilians, 37–41 Achuzia, Simon Uchenna, 109 federal troops occupy, 35–37 Action Group (AG), 7 history as de facto capital of Nigeria, 23 Ade, Sunny, 172 indigeneity. See Ahaba identity Adebayo, Robert Adeyinka, 93 kindness of some Federal soldiers, 55–56 Adib, Ifeanyi, 188 massacre of Oct. 7, 42–51 Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi, 181 monument to massacre victims, 203 Agbor, 13, 28, 101, 144 plans to welcome federal troops, 41–42 Agbor, reported violence by Biafrans, 16 refugee camp at, 116, 117, 132, 133, Aguiyi-Ironsi, Johnson, 8, 9 141, 143 Ahaba identity, 25, 188, 196, 197, 198, 200 relief operations in, 86, 94, 133, 138, 139, Aisida, Francis, 17, 58 140, 141, 147 Akaraiwe, Joseph, 129 Second Operation, 129, 130, 135, 137, Akaraiwe, Patricia, 129, 140 138, 141, 163 Akintola, Samuel, 7, 8 significance of massacre, 212–217 Akpan, N.U., 67, 110 social structure in, 22 Akundele, Benjamin, 114, 115 St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, 44, 133, akwa ocha attire, 41, 162 149 Alabi-Isama, Godwin, 13 support for united Nigeria, 30 Alli, Chris, -

Copyright by Brian Edward Mcneil 2014

Copyright by Brian Edward McNeil 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Brian Edward McNeil certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Frontiers of Need: Humanitarianism and the American Involvement in the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970 Committee: Mark Atwood Lawrence, Supervisor Toyin Falola Jeremi Suri H.W. Brands Thomas Borstelmann Frontiers of Need: Humanitarianism and the American Involvement in the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970 by Brian Edward McNeil, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 Who will rise up for me against the wicked? Who will take a stand for me against evildoers? Psalm 94:16 For Noelle Acknowledgements No one ever told me that dissertations are built upon debts and broken promises. When I first entered the University of Texas at Austin in 2007 to begin my doctoral studies, I had a clear plan for finishing. I knew that I wanted to write on the United States and the Nigerian Civil War, which, as it turns out, was a good start. I promised my wife it would take five years to finish. Seven years later, I have completed my degree. Part of the reason for the delay was that I discovered that the Nigerian Civil War was a much larger event with much more import than scholars have realized. My dissertation required research on three continents and numerous cities: from Los Angeles, to London, to Lagos. -

Article 15 Communication to the Icc Office of the Prosecutor Regarding the Targeting of the Pro-Biafran Independence Movement in Nigeria

ARTICLE 15 COMMUNICATION TO THE ICC OFFICE OF THE PROSECUTOR REGARDING THE TARGETING OF THE PRO-BIAFRAN INDEPENDENCE MOVEMENT IN NIGERIA * * * I. INTRODUCTION 1. This communication is hereby filed to the Office of the Prosecutor (the ‘OTP’) of the International Criminal Court (the ‘ICC’) pursuant to Article 15 of the Rome Statute (the ‘Statute’) by Professor Göran Sluiter1 and Andrew Ianuzzi2 on behalf of the Indigenous People of Biafra (‘IPOB’), a movement dedicated to the self-determination of the former Republic of Biafra in South-Eastern Nigeria, as well as on behalf of 17 individual citizens of Nigeria3 (the ‘Victims’) (collectively, with the IPOB, the ‘Petitioners’). 2. The Petitioners submit that, based on the information set out herein, there is reason to believe that crimes against humanity within the jurisdiction of the ICC—in particular: murder, unlawful imprisonment, torture, enforced disappearance, other inhumane acts, and persecution—have been committed in the context of politically- and ethnically-motivated state violence against, primarily, IPOB members and the Igbo people of South-Eastern Nigeria. Due to the absence of domestic criminal proceedings with respect to those potentially bearing the greatest responsibility for these crimes—in particular, but not limited to, Nigeria’s current president Muhammadu Buhari—and in the light of the gravity of the acts committed, the Petitioners further submit that the case would be admissible under Article 17 of the Statute. Moreover, based on the available information, there is no reason to believe that the opening of a preliminary 1 Professor Sluiter holds a chair in international criminal law at the Faculty of Law at the University of Amsterdam and is a partner at the Amsterdam law firm of Prakken d’Oliveira Human Rights Lawyers.