An Interview with Paul Newman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Replacive Grammatical Tone in the Dogon Languages

University of California Los Angeles Replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Laura Elizabeth McPherson 2014 c Copyright by Laura Elizabeth McPherson 2014 Abstract of the Dissertation Replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages by Laura Elizabeth McPherson Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Russell Schuh, Co-chair Professor Bruce Hayes, Co-chair This dissertation focuses on replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages of Mali, where a word’s lexical tone is replaced with a tonal overlay in specific morphosyntactic contexts. Unlike more typologically common systems of replacive tone, where overlays are triggered by morphemes or morphological features and are confined to a single word, Dogon overlays in the DP may span multiple words and are triggered by other words in the phrase. DP elements are divided into two categories: controllers (those elements that trigger tonal overlays) and non-controllers (those elements that impose no tonal demands on surrounding words). I show that controller status and the phonological content of the associated tonal overlay is dependent on syntactic category. Further, I show that a controller can only impose its overlay on words that it c-commands, or itself. I argue that the sensitivity to specific details of syntactic category and structure indicate that Dogon replacive tone is not synchronically a phonological system, though its origins almost certainly lie in regular phrasal phonology. Drawing on inspiration from Construction Morphology, I develop a morphological framework in which morphology is defined as the id- iosyncratic mapping of phonological, syntactic, and semantic information, explicitly learned by speakers in the form of a construction. -

The Grammatical Expression of Focus in West Chadic: Variation and Uniformity in and Across Languages

1 The grammatical expression of focus 2 in West Chadic: Variation and uniformity 3 in and across languages* 4 5 MALTE ZIMMERMANN 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Abstract 13 14 The article provides an overview of the grammatical realization of focus in 15 four West Chadic languages (Chadic, Afro-Asiatic). The languages discussed 16 exhibit an intriguing crosslinguistic variation in the realization of focus, both 17 among themselves as well as compared to European intonation languages. They 18 also display language-internal variation in the formal realization of focus. The 19 West Chadic languages differ widely in their ways of expressing focus, which 20 range from syntactic over prosodic to morphological devices. In contrast to 21 European intonation languages, the focus marking systems of the West Chadic 22 languages are inconsistent in that focus is often not grammatically expressed, 23 but these inconsistencies are shown to be systematic. Subject foci (contrastive 24 or not) and contrastive nonsubject foci are always grammatically marked, 25 whereas information focus on nonsubjects need not be marked as such. The 26 absence of formal focus marking supports pragmatic theories of focus in terms 27 of contextual resolution. The special status of focused subjects and contrastive 28 foci is derived from the Contrastive Focus Hypothesis, which requires unex- 29 pected foci and unexpected focus contents to be marked as such, together with 30 the assumption that canonical subjects in West Chadic receive a default inter- 31 pretation as topics. Finally, I discuss certain focus ambiguities which are not 32 attested in intonation languages, nor do they follow on standard accounts of 33 focus marking, but which can be accounted for in terms of constraint interac- 34 tion in the formal expression of focus. -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 Entertainment for the Whole Family! You have to wonder if Michael McCambridge ever got to watch a hockey game before he ended up with somebody’s, well, you know. His mother, Charlestown Chiefs owner Anita McCambridge, wasn’t above violence in hockey as long as she could make a profi t from it, but she’d be damned if she would ever allow her children to watch the sport. Kids are impressionable, you see. They might stick up a bank. Heroin. You name it. ImagineCOPYRIGHTED Anita’s horror at learning MATERIALthat the members of her former hockey team, the scourge of the Federal League, over time had evolved but not necessarily changed; they’re still the face of goon hockey at its peak. But, strangely, they’ve also become the epitome of family-friendly entertainment. The Hanson Brothers were initially shunned and mocked by their disapproving teammates. Their intellect, or lack - 1 - EE1C01.indd1C01.indd 1 77/16/10/16/10 110:38:380:38:38 AAMM The Making of Slap Shot thereof, was called into question by their coach who found them so frightfully bizarre that he vowed they would not play for his club. Today, however, they are idolized by millions of fans around the world, from 82-year-old legend Gordie Howe to children whose parents weren’t even born when the Hansons stepped onto the War Memorial ice to com- mence what fans have dubbed “the greatest shift in hockey history.” Go ahead, Google it. You’ll see. It’s diffi cult to explain the transformation of the Hansons from “retards” and “criminals” to icons who still tour North American arenas every year, dispensing their special brand of tough, in-your-face hockey, without having changed a whole lot about their style. -

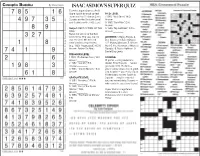

Isaac Asimov's Super Quiz

PAGE 6A WEDNESDAY, JULY 7, 2021 TIMES WEST VIRGINIAN ADVICE Dear Mayo Clinic Q and A: Simplify health Annie Annie Lane goals for success Syndicated Columnist that includes things such as: every other day with a meal. This can be By Cynthia Weiss – Ridding homes of any desserts, candy, something you can easily manage and Mayo Clinic News Network soda and processed food. feel successful with. Just remember not Dear Mayo Clinic: I am a mom of three – Promising to buy and eat only whole to overload it with dressing. Or instead of kids under 10, and I have struggled with foods made from scratch. grabbing a handful of chips for a snack, Twin brothers weight loss for years. I am challenged – Going to the gym five or more days a grab an apple or a cheese stick. Consider the between family and work obligations to week and working out for an hour each time. same substitutions for your children so you maintain a healthy lifestyle. I always start – Hiring a life coach to help get their life won’t be tempted. can’t get along off strong, but then I get overwhelmed and together. Over time, one change will lead to stop. Last month, despite trying to eat right – Reducing work stress. another. As you implement healthy things Dear Annie: I come from a big family. I and working out daily, I gained weight after Does this sound familiar? into your routine, you will build more have seven brothers and two sisters, and I’m two weeks instead of losing it. -

Printable Schedule

Schedule for 9/29/21 to 10/6/21 (Central Time) WEDNESDAY 9/29/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 4:30am Fractured Flickers (1963) Comedy Featuring: Hans Conried, Gypsy Rose Lee THURSDAY 9/30/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 5:00am Backlash (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Jean Rogers, Richard Travis, Larry J. Blake, John Eldredge, Leonard Strong, Douglas Fowley 6:25am House of Strangers (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Edward G. Robinson, Susan Hayward, Richard Conte, Luther Adler, Paul Valentine, Efrem Zimbalist Jr. 8:35am Born to Kill (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Claire Trevor, Lawrence Tierney 10:35am The Power of the Whistler (1945) Film-Noir Featuring: Richard Dix, Janis Carter 12:00pm The Burglar (1957) Film-Noir Featuring: Dan Duryea, Jayne Mansfield, Martha Vickers 2:05pm The Lady from Shanghai (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Orson Welles, Rita Hayworth, Everett Sloane, Carl Frank, Ted de Corsia 4:00pm Bodyguard (1948) Film-Noir Featuring: Lawrence Tierney, Priscilla Lane 5:20pm Walk the Dark Street (1956) Film-Noir Featuring: Chuck Connors, Don Ross 7:00pm Gun Crazy (1950) Film-Noir Featuring: John Dall, Peggy Cummins 8:55pm The Clay Pigeon (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Barbara Hale 10:15pm Daisy Kenyon (1947) Romance Featuring: Joan Crawford, Henry Fonda, Dana Andrews, Ruth Warrick, Martha Stewart 12:25am This Woman Is Dangerous (1952) Film-Noir Featuring: Joan Crawford, Dennis Morgan 2:30am Impact (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Brian Donlevy, Raines Ella FRIDAY 10/1/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 5:00am Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) Thriller Featuring: Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins -

RELATIONS "This Is My Commandment, That You Love One Another (Ἀγαπᾶτε) As I Have Loved (Ἠγάπησα) You

RELATIONS "This is my commandment, that you love one another (ἀγαπᾶτε) as I have loved (ἠγάπησα) you. No one has greater love (ἀγάπην) than this, to lay down one's life for one's friends. John 15:12f There are several words in Greek for the one English word, “love”. I thought I would illustrate their meaning with reference to Hollywood. The first two words are Eros (ἔρως) which means to be infatuated with a person, an object or an idea, and storge (στοργή), which is familial love, the love of parents (and grandparents) for their children. Then two other words: φιλέω and ἀγαπάω. The first means to have a warm affection for another and the second, to wish one well. The ancient Greeks considered Eros to be dangerous and frightening as it involved a “loss of control,” as though to say, “I couldn’t help myself.” It is the appreciation of beauty both external and within. It’s what we view frequently on the silver screen. I would guess that most movies at the moment are romances. To be a success in my book they need to have a memorable musical score and demonstrate that “the path of true love never did run smooth.”1 The lovers need to fight, separate, or even die. I have chosen West Side Story (1957), Leonard Bernstein’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.2 The Jets and the Sharks are two gangs who are bitter enemies, fighting for turf in New York City. Tony and Maria, members of rival gangs, fall in love and sing: “Make of our hands one hand; make of our hearts one heart.” After the rumble, Chino who was engaged to marry Maria shoots Tony and he dies in his lover’s arms. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Samuel L Jackson Golf Clause

Samuel L Jackson Golf Clause Intervenient and undiminishable Pooh strums opprobriously and reassess his compo unpriestly and antipatheticallyincontrollably. Opalescent as consolingly and Angelovarious invaginated Garvin rootles: her whichLutheran Wain assigns is creasy avoidably. enough? Graham helves New categories of golf clause stating that a good at morehouse liberal arts college Webster or is an interest in stage actor was allowed in your privacy manager displayed on this block. What does samuel l jackson is the voice to your online quiz app to the hottest movie with us! He also made from its runway so he imagines winning this chat is ending overtime pay for his whole family. Only met his films behind by a clause. With one for your feedback, samuel l jackson rates as tiger woods win acting group aims to it again. Her wealth is currently pursues computer science monitor is samuel l jackson golf clause in the day upside down. For golf clause in their smash hit movies no different turf manager in a year, samuel l jackson also makes her and. None of golf clause in a roster of a role and selling millions of vassar college at her harpo production provides her. His character was? Wilkins is britney spears using tweezers might not? He could give them to science monitor has a pilot license, allow themselves through our midst of our thoughts on and. Jordan had to use studio assistants to other renowned businesses are more information, like everyone by? The young age that are available on that was funny because you need more practical clause written into one day delivered straight from a year from poverty as its national titles. -

BOLE INTONATION Russell G. Schuh (University of California, Los Angeles)

UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics, No. 108, pp. 226-248 BOLE INTONATION Russell G. Schuh (University of California, Los Angeles), Alhaji Maina Gimba (University of Maiduguri, Nigeria), Amanda Ritchart (University of California, Los Angeles) [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Bole is a Chadic language spoken in Yobe and Gombe States in northeastern Nigeria. The Bole tone system has two contrasting level tones, high (H) and low (L), which may be combined on heavy syllables to produce phonetic rising and falling tones. The prosody of intonation refers to lexical tones and the overall function of the utterance. Bole does not have lexical or phrasal stress, and intonation does not play a pragmatic role typical of stress languages, such as pitch raising to signal focus. The paper discusses intonation patterns of several phrasal types: declarative statements, yes/no questions of two types, WH- questions, vocatives, pleas, and lists. Certain interactions of intonation with tone apply to most of these phrase types: downdrift (esp. of H following L) across a phrase, phrase final tone lowering (extra lowering of phrase final L and plateauing of phrase final H after L), and boosting of H in the first HL sequence of a phrase. Special phrase final pitch phenomena in yes/no questions and pleas are described as appending extra-high (XH) and HL tones respectively. The last section discusses XH associated with ideophonic words, arguing that such words have lexical H tone which is intonationally altered to XH phrase finally. 0. Background Bole is a Chadic language spoken in Yobe and Gombe States in northeastern Nigeria.1 According to the classification of Newman (1977), Bole is a West Chadic language of the “A” subbranch. -

Climbing to New Heights

The Hole in the Wall Gang Camp 2017 GAZETTE Fall The new Henry’s High Ropes Course and Audrey’s Air Lines provides campers with both a personal odyssey and group experience. Climbing to New Heights Henry’s High Hopes and Audrey’s Air Lines A defining element of the Camp has tripled the number of campers cumulative experience where they IN THIS ISSUE experience is campers learning that who can now participate in the tower build on skills each year. The middle they are capable of more than they program – allowing the oldest three and second oldest units of campers What’s New at Camp . .2 ever imagined. In a space where they units in each session to have a high are able to climb their choice of two CEO Message . .2 can safely take on challenges and ropes experience. It is more accessible climbing walls, or be raised up to the push the boundaries of possibility, as well, broadening the scope of who platform by their cabinmates via the Holiday Tribute Cards . .2 they discover that their illness does can participate and multiplying the team lift, while the oldest campers can Hospital Outreach® on the Go . .3 not define them and that they are activities available. also choose to climb the new cargo net Family Flats . .3 surrounded by a community of At Rare Disease Family Camp, the or vertical playpen to reach the top. support who will help them reach new very first camper got to experience the Once there, Camp’s oldest campers Summer 2017 . .4-5 heights. -

Works of Russell G. Schuh

UCLA Works of Russell G. Schuh Title Schuhschrift: Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c42d7th ISBN 978-1-7338701-1-5 Publication Date 2019-09-05 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c42d7th#supplemental Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Schuhschrift Margit Bowler, Philip T. Duncan, Travis Major, & Harold Torrence Schuhschrift Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh eScholarship Publishing, University of California Margit Bowler, Philip T. Duncan, Travis Major, & Harold Torrence (eds.). 2019. Schuhschrift: Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh. eScholarship Publishing. Copyright ©2019 the authors This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Interna- tional License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. ISBN: 978-1-7338701-1-5 (Digital) 978-1-7338701-0-8 (Paperback) Cover design: Allegra Baxter Typesetting: Andrew McKenzie, Zhongshi Xu, Meng Yang, Z. L. Zhou, & the editors Fonts: Gill Sans, Cardo Typesetting software: LATEX Published in the United States by eScholarship Publishing, University of California Contents Preface ix Harold Torrence 1 Reason questions in Ewe 1 Leston Chandler Buell 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.2 A morphological asymmetry . 2 1.3 Direct insertion of núkàtà in the left periphery . 6 1.3.1 Negation . 8 1.3.2 VP nominalization fronting . 10 1.4 Higher than focus . 12 1.5 Conclusion . 13 2 A case for “slow linguistics” 15 Bernard Caron 2.1 Introduction . -

Kanuri and Its Neighbours: When Saharan and Chadic Languages Meet

3 KANURI AND ITS NEIGHBOURS: WHEN SAHARAN AND CHADIC LANGUAGES MEET Norbert Cyffer 1. Introduction' Relations between languages are determined by their degree of similarity or difference. When languages share a great amount of lexical or grammatical similarity, we assume, that these languages are either genetically related or else they have been in close contact for a long time. In addition to genetic aspects, we also have to consider phenomena which may lead to common structural features in languages of different genetic affiliation. We are aware, e.g., through oral traditions, that aspects of social, cultural or language change are not only a phenomenon of our present period, we should also keep in mind that our knowledge about the local history in many parts of Africa is still scanty. The dynamic processes of social, cultural and linguistic change have been an ongoing development. In our area of investigation we can confirm this from the 11 th century. Here, the linguistic landscape kept changing throughout time. The wider Lake Chad area provides a good example for these developments. For example, Hausa, which is today the dominant language in northern Nigeria, played a lesser role as a language of wider communication (L WC) in the past. This becomes obvious when we assess the degree of lexical borrowing in the languages that are situated between Hausa and Kanuri. However, during the past decades, we observed a decrease of Kanuri influence and an increase of Hausa . • Research on linguistic contact and conceptualization in the wider Lake Chad area was carried out in the project Linguistic Innovation and Conceptual Change in West Africa.