Master Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investor Info August 2018

Investor Relations Investor Info August 2018 Lufthansa Group Month yoy Cumulative yoy Passengers in 1,000 13,755 +10.0% 94,840 +11.2% Available seat-kilometers (m) 32,925 +8.2% 232,705 +8.0% Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 28,434 +8.7% 189,951 +8.8% Total Lufthansa Group Passenger load-factor (%) 86.4 +0.5pts. 81.6 +0.6pts. Airlines Available Cargo tonne-kilometers (m) 1,416 +3.6% 10,782 +4.2% Revenue Cargo tonne-kilometers (m) 895 -0.7% 7,170 +1.7% Cargo load-factor (%) 63.2 -2.7pts. 66.5 -1.7pts. Number of flights 111,408 +10.0% 813,719 +8.7% Passengers in 1,000 6,509 +7.3% 46,708 +7.3% Available seat-kilometers (m) 18,087 +4.0% 131,537 +4.4% Lufthansa German Airlines* Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 15,571 +4.3% 107,345 +4.3% Passenger load-factor (%) 86.1 +0.3pts. 81.6 -0.1pts. Number of flights 50,832 +8.6% 383,883 +6.7% Passengers in 1,000 4,153 +5.0% 29,075 +5.0% Available seat-kilometers (m) 12,739 +1.1% 92,374 +1.8% thereof Hub FRA Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 10,982 +0.9% 75,672 +1.3% Passenger load-factor (%) 86.2 -0.2% 81.9 -0.4% Number of flights 30,902 +7.9% 226,998 +6.3% Passengers in 1,000 2,256 +11.2% 16,921 +10.9% Available seat-kilometers (m) 5,271 +11.3% 38,657 +11.0% thereof Hub MUC Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 4,538 +13.4% 31,338 +11.9% Passenger load-factor (%) 86.1 +1.6% 81.1 +0.7% Number of flights 18,620 +8.6% 147,417 +6.7% Passengers in 1,000 2,033 +10.6% 13,667 +9.4% Available seat-kilometers (m) 5,555 +9.0% 39,965 +7.7% SWISS Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 4,877 +9.4% 33,148 +9.1% Passenger load-factor (%) 87.8 +0.3pts. -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Magisterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MAGISTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Magisterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis Wahrnehmung und Bewertung von Krisenkommunikation Eine Untersuchung am Beispiel des Flugzeugunglücks der Lufthansa-Tochter Germanwings am 24. März 2015 verfasst von / submitted by Raffaela ECKEL, Bakk. phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2016 / Vienna, 2016 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: A 066 841 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Publizistik- und Kommunikationswissenschaft Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Sabine Einwiller Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich ge- macht. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen Prü- fungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Wien, August 2016 Raffaela Eckel Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einführung und Problemstellung ......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Theoretische Hinführung: Beitrag der Wissenschaft zu einer gelungenen Krisenkommunikation.................................................................................................... 2 1.2 -

Edelweiss Presents New Aircraft Design

Press release Zurich Airport, 13 November 2015 Edelweiss presents new aircraft design In future, Edelweiss aircraft will be seen in a new design. The new look supports the leading Swiss leisure travel airline's growth course, and underscores its origins. As well as the new aircraft design, Edelweiss will also modernise the interior of its entire Airbus A320 fleet and install a Wireless Inflight Entertainment System. The Edelweiss aircraft will be seen in their new "clothes" in time for the airline's 20th anniversary. The current livery has remained the same since the company was founded. Bernd Bauer, CEO of Edelweiss: "We are proud of what we have achieved in the past, and we are taking this success with us into the future. We chose our new aircraft design to be an evolution, rather than a revolution." Familiar details such as the red noses on the aircraft will be left unchanged. The most eye-catching details are the oversized Edelweiss flower on the tail fin and the addition of the word "Switzerland" on the aircraft. "We want to clearly express our Swiss origins. We provide connections to the loveliest holiday destinations in Switzerland, and we delight people with Swiss quality. And we want our aircraft to reflect this," he adds. The first Airbus A320 in the new design will start travelling on the Edelweiss network at the end of November 2015. Wireless Inflight Entertainment System on the entire Airbus A320 fleet Over the coming months, Edelweiss will also convert all six of its Airbus A320s. They are all being given a new cabin, which will increase people's anticipation of their holiday as soon as they board. -

Crisis Communication

Crisis communication The case of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic Marlies Nittmann Supervisor: Robert Ciuchita Department of Marketing Hanken School of Economics Helsinki 2021 i HANKEN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Department of: Type of work: Marketing Master’s Thesis Author: Date: 31.3.2021 Marlies Nittmann Title of thesis: Crisis Communication: The case of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic Abstract: Due to the increasing frequency of crises and the diversification of their causes, a wide range of research has been completed in this field. However, the crisis communication literature has not yet thoroughly covered the topic of public health crises and the corporate communication during such a global event. Further, examples of crisis communication used by companies in particular industries are limited. Therefore, this thesis studies the crisis communication literature to receive a better understanding of the theory before looking at the corporate communications from four European airline companies. A comparative case study approach is used in order to receive an insight into the communication strategies applied by the aviation industry during a pandemic. A quantitative study is conducted, and the web pages, newsletters and press releases are analysed. Based on the conducted research, six main topics of communication are established and compared to the previous findings of the literature. Even though the four case companies share similar information with their stakeholders, they differ in the way they approach the messages, how they communicate and when they engage with their stakeholders. This study adds to the crisis communication literature focusing on public health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to the literature covering crisis communication in the aviation industry. -

Air Transport Industry Analysis Report

Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2016 Final Report March 2017 European Commission Annual Analyses related to the EU Air Transport Market 2016 328131 ITD ITA 1 F Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2013 Final Report March 2015 Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2013 MarchFinal Report 201 7 European Commission European Commission Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate General for Mobility and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract MOVE/E1/5-2010/SI2.579402. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European Commission's or the Mobility and Transport DG's views. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the information given in the report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. Copyright in this report is held by the European Communities. Persons wishing to use the contents of this report (in whole or in part) for purposes other than their personal use are invited to submit a written request to the following address: European Commission - DG MOVE - Library (DM28, 0/36) - B-1049 Brussels e-mail (http://ec.europa.eu/transport/contact/index_en.htm) Mott MacDonald, Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 8774 2000 F +44 (0)20 8681 5706 W www.mottmac.com Issue and revision record StandardSta Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description ndard A 28.03.17 Various K. -

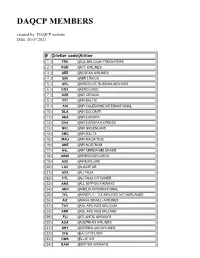

DAQCP MEMBERS Created By: DAQCP Website Date: 20.07.2021

DAQCP MEMBERS created by: DAQCP website Date: 20.07.2021 # 3-letter code Airline 1 FRH ACE BELGIUM FREIGHTERS 2 RUN ACT AIRLINES 3 AEE AEGEAN AIRLINES 4 EIN AER LINGUS 5 AFL AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES 6 BOX AEROLOGIC 7 KZR AIR ASTANA 8 BTI AIR BALTIC 9 ACI AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 10 DLA AIR DOLOMITI 11 AEA AIR EUROPA 12 OVA AIR EUROPA EXPRESS 13 GRL AIR GREENLAND 14 AMC AIR MALTA 15 MAU AIR MAURITIUS 16 ANE AIR NOSTRUM 17 ASL AIR SERBIA BELGRADE 18 ABW AIRBRIDGECARGO 19 AXE AIREXPLORE 20 LAV ALBASTAR 21 AZA ALITALIA 22 CYL ALITALIA CITYLINER 23 ANA ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS 24 AEH AMELIA INTERNATIONAL 25 TFL ARKEFLY - TUI AIRLINES NETHERLANDS 26 AIZ ARKIA ISRAELI AIRLINES 27 TAY ASL AIRLINES BELGIUM 28 ABR ASL AIRLINES IRELAND 29 FLI ATLANTIC AIRWAYS 30 AUA AUSTRIAN AIRLINES 31 AHY AZERBAIJAN AIRLINES 32 CFE BA CITYFLYER 33 BMS BLUE AIR 34 BAW BRITISH AIRWAYS 35 BEL BRUSSELS AIRLINES 36 GNE BUSINESS AVIATION SERVICES GUERNSEY LTD 37 CLU CARGOLOGICAIR 38 CLX CARGOLUX AIRLINES INTERNATIONAL S.A 39 ICV CARGOLUX ITALIA 40 CEB CEBU PACIFIC 41 BCY CITYJET 42 CFG CONDOR FLUGDIENST GMBH 43 CTN CROATIA AIRLINES 44 CSA CZECH AIRLINES 45 DLH DEUTSCHE LUFTHANSA 46 DHK DHL AIR LTD. 47 EZE EASTERN AIRWAYS 48 EJU EASYJET EUROPE 49 EZS EASYJET SWITZERLAND 50 EZY EASYJET UK 51 EDW EDELWEISS AIR 52 ELY EL AL 53 UAE EMIRATES 54 ETH ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 55 ETD ETIHAD AIRWAYS 56 MMZ EUROATLANTIC 57 BCS EUROPEAN AIR TRANSPORT 58 EWG EUROWINGS 59 OCN EUROWINGS DISCOVER 60 EWE EUROWINGS EUROPE 61 EVE EVELOP AIRLINES 62 FIN FINNAIR 63 FHY FREEBIRD AIRLINES 64 GJT GETJET AIRLINES 65 GFA GULF AIR 66 OAW HELVETIC AIRWAYS 67 HFY HI FLY 68 HBN HIBERNIAN AIRLINES 69 HOP HOP! 70 IBE IBERIA 71 ICE ICELANDAIR 72 ISR ISRAIR AIRLINES 73 JAL JAPAN AIRLINES CO. -

2015 REVIEW • Ryanair Introduces Direct Flights from Larnaka to Brussels

2016 REVIEW SPONSORED BY: 1 www.atn.aero 2015 REVIEW • Ryanair introduces direct flights from Larnaka to Brussels JANUARY 4/1/2016 14/1/2016 • Etihad Airways today launched fresh legal action in a bid to overturn a German court’s decision to revoke the approval for 29 of its • Genève Aéroport welcomed a total of nearly 15.8 million passengers codeshare flights with airberlin in 2015 • ALTA welcomes Enrique Cueto as new President of its Executive 5/1/2016 Committee • Spirit Airlines, Inc. today announced Robert L. Fornaro has been appointed President and Chief Executive Officer, effective immediately 6/1/2016 • FAA releases B4UFLY Smartphone App 7/1/2016 • The International Air Transport Association (IATA) announced it is expanding its activities to prevent payment fraud in the air travel industry • Boeing delivered 762 commercial airplanes in 2015, 39 more than the previous year and most ever for the company as it enters its centennial year • Rynair become the first airline to carry over 100m international Source: LATAM customers in one year • American Airlines and LATAM Airlines Group are applying for • BOC Aviation orders 30 A320 Family regulatory approval to enter into a joint business (JB) to better serve their customers • Bordeaux Airport 2015 review: Nearly 5,300,000 passengers in 2015: growth of +7.6% 15/1/2016 • Etihad Airways today welcomed the ruling by the higher administrative 8/1/2016 court in Luneburg reversing an earlier judgment and allowing it to • The European Commission has approved under the EU Merger continue operating -

Investor Info March 2016

Beispiel, keine realistischen Zahlen Investor Info March 2016 Lufthansa Group Month yoy (%) Cumulative yoy (%) Passengers in 1,000 8,418 +4.0 22,331 +3.6 Available seat-kilometers (m) 22,682 +6.8 62,785 +6.6 Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 17,350 +5.4 47,032 +5.2 Total Passenger load-factor (%) 76.5 -1.0pts. 74.9 -0.9pts. Lufthansa Group Available Cargo tonne-kilometers (m) 1,243 -3.8 3,425 -1.2 Airlines Revenue Cargo tonne-kilometers (m) 826 -10.5 2,264 -6.2 Cargo load-factor (%) 66.4 -5.0pts. 66.1 -3.5pts. Number of flights 82,536 +1.9 232,437 +2.8 Passengers in 1,000 4,937 +4.2 13,277 +3.1 Available seat-kilometers (m) 15,089 +6.0 41,531 +5.2 Lufthansa Passenger Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 11,537 +5.1 31,224 +4.2 Airlines Passenger load-factor (%) 76.5 -0.6pts. 75.2 -0.7pts. Number of flights 44,410 +1.7 126,188 +2.0 Passengers in 1,000 1,364 -0.6 3,698 -0.6 Available seat-kilometers (m) 4,053 +1.9 11,658 +2.1 SWISS Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 3,141 -2.9 8,848 -1.7 Passenger load-factor (%) 77.5 -3.8pts. 75.9 -2.9pts. Number of flights 13,541 +2.9 38,905 +3.3 Passengers in 1,000 819 +3.9 2,053 +3.7 Available seat-kilometers (m) 1,828 +8.7 4,926 +8.3 Austrian Airlines Revenue seat-kilometers (m) 1,341 +5.4 3,506 +5.4 Passenger load-factor (%) 73.3 -2.3pts. -

World Air Transport Statistics, Media Kit Edition 2021

Since 1949 + WATSWorld Air Transport Statistics 2021 NOTICE DISCLAIMER. The information contained in this publication is subject to constant review in the light of changing government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or other reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/ or without taking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the International Air Transport Associ- ation shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Fur- thermore, the International Air Transport Asso- ciation expressly disclaims any and all liability to any person or entity, whether a purchaser of this publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, and the consequences of anything done or omitted, by any such person or entity in reliance on the contents of this publication. Opinions expressed in advertisements ap- pearing in this publication are the advertiser’s opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of IATA. The mention of specific companies or products in advertisement does not im- ply that they are endorsed or recommended by IATA in preference to others of a similar na- ture which are not mentioned or advertised. © International Air Transport Association. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, recast, reformatted or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval sys- tem, without the prior written permission from: Deputy Director General International Air Transport Association 33, Route de l’Aéroport 1215 Geneva 15 Airport Switzerland World Air Transport Statistics, Plus Edition 2021 ISBN 978-92-9264-350-8 © 2021 International Air Transport Association. -

Sustainability 2019 2 INTRO

FACT SHEET ONLINE lufthansagroup.com/en/responsibility FACT SHEET FACT Sustainability 2019 Sustainability 2 INTRO The responsible and sustainable treatment of resources, the environment and society is a prerequisite for the long-term financial stability and attractiveness of the Lufthansa Group for its customers, employees, investors and partners. With its measures and concepts, the Lufthansa Group aims to strengthen the positive effects of its business activities and further reduce the negative impacts in order to consolidate its position as a leading player in the airline industry, including in the area of corporate responsibility. You will find further information, the strategic direction and targets in the non-financial declaration of the annual report 2019. ↗ investor-relations.lufthansagroup.com The Executive Board has been extended to include a position responsible for Customer & Corporate Responsibility since 1 January 2020. This will establish responsibility for environment, climate and society directly at the Executive Board level. The Company has applied the principles of the UN Global Compact for sustainable and responsible corporate governance since 2002. A Supplier Code of Conduct has supplemented the Code of Conduct, which has been binding for all corporate bodies, managers and employees since 2017. The Lufthansa Group supports the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the Agenda 2030, as adopted by the UN member states in 2015 and is concentrating on the seven SDGs 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13 and 17 due to the impacts of its business -

AIRLINES Monthly

AIRLINES monthly OTP JUNE 2017 Contents GLOBAL AIRLINES GLOBAL RANKING Top and bottom Regional airlines Latin North EMEA ASPAC American and America Caribbean Notes: % On-Time is percentage of flights that depart or Update: Status coverage as of JUNE 2017 will only be arrive within 15 minutes of schedule. based on actual gate times rather than estimated times. This Source: OAG flightview. Any reuse, publication or distribution may result in some airlines/airports being excluded from this of report data must be attributed to OAG flightview. report. Global OTP rankings are assigned to all airlines/ Global OTP rankings are assigned to all Airports airports where OAG has status coverage for at least 80% where OAG has status coverage for at least 80% of the of scheduled flights. If you would like to review your flight scheduled flights. status feed with OAG please [email protected] AIRLINE MONTHLY OTP – JUNE 2017 Global airlines – top and bottom BOTTOM AIRLINE ON-TIME TOP AIRLINE ON-TIME FLIGHTS On-time performance On-time performance FLIGHTS Airline Arrivals Rank Flights Rank Airline Arrivals Rank Flights Rank HR Hahn Air 93.3% 1 16 376 ZH Shenzhen Airlines 32.0% 141 19,585 28 TW T'way Air 92.9% 2 1,653 211 MF Xiamen Airlines Company 41.3% 140 17,190 40 RC Atlantic Airways Faroe Islands 91.0% 3 304 323 HU Hainan Airlines 45.9% 139 21,017 25 SATA International-Azores BC Skymark Airlines 91.0% 4 3,900 134 S4 48.0% 138 811 271 Airlines S.A. PM Canaryfly 90.5% 5 772 276 CZ China Southern Airlines 48.6% 137 59,619 6 DVR Divi Divi Air 89.5% 6 354 317 CA Air China 49.7% 136 38,029 12 JL Japan Airlines 89.3% 7 23,636 21 MU China Eastern Airlines 50.7% 135 57,194 7 HA Hawaiian Airlines 89.1% 8 8,440 80 KA Cathay Dragon 52.1% 134 5,042 120 BT Air Baltic Corporation 88.9% 9 4,594 124 3H Air Inuit 54.7% 133 1,506 221 QF Qantas Airways 88.6% 10 21,798 24 PD Porter Airlines Inc.