Chapter 6 Tule Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

1 Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain

Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain, Co-Ordinator TrailSafe Nevada 1285 Baring Blvd. Sparks, NV 89434 [email protected] Nev. Dept. of Cons. & Natural Resources | NV.gov | Governor Brian Sandoval | Nev. Maps NEVADA STATE PARKS http://parks.nv.gov/parks/parks-by-name/ Beaver Dam State Park Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park Big Bend of the Colorado State Recreation Area Cathedral Gorge State Park Cave Lake State Park Dayton State Park Echo Canyon State Park Elgin Schoolhouse State Historic Site Fort Churchill State Historic Park Kershaw-Ryan State Park Lahontan State Recreation Area Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park Sand Harbor Spooner Backcountry Cave Rock Mormon Station State Historic Park Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park Rye Patch State Recreation Area South Fork State Recreation Area Spring Mountain Ranch State Park Spring Valley State Park Valley of Fire State Park Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park Washoe Lake State Park Wild Horse State Recreation Area A SOURCE OF INFORMATION http://www.nvtrailmaps.com/ Great Basin Institute 16750 Mt. Rose Hwy. Reno, NV 89511 Phone: 775.674.5475 Fax: 775.674.5499 NEVADA TRAILS Top Searched Trails: Jumbo Grade Logandale Trails Hunter Lake Trail Whites Canyon route Prison Hill 1 TOURISM AND TRAVEL GUIDES – ALL ONLINE http://travelnevada.com/travel-guides/ For instance: Rides, Scenic Byways, Indian Territory, skiing, museums, Highway 50, Silver Trails, Lake Tahoe, Carson Valley, Eastern Nevada, Southern Nevada, Southeast95 Adventure, I 80 and I50 NEVADA SCENIC BYWAYS Lake -

Nesting Populations of California and Ring-Billed Gulls in California

WESTERN BIR Volume 31, Number 3, 2000 NESTING POPULATIONS OF CLwO AND RING-BI--F-r GULLS IN CALIFORNIA: RECENT SURVEYS AND HISTORICAL STATUS W. DAVID SHUFORD, Point Reyes Bird Observatory(PRBO), 4990 Shoreline Highway, StinsonBeach, California94970 THOMAS P. RYAN, San FranciscoBay Bird Observatory(SFBBO), P.O. Box 247, 1290 Hope Street,Alviso, California 95002 ABSTRACT: Statewidesurveys from 1994 to 1997 revealed33,125 to 39,678 breedingpairs of CaliforniaGulls and at least9611 to 12,660 pairsof Ring-billed Gullsin California.Gulls nested at 12 inland sitesand in San FranciscoBay. The Mono Lake colonywas by far the largestof the CaliforniaGull, holding 70% to 80% of the statepopulation, followed by SanFrancisco Bay with 11% to 14%. ButteValley WildlifeArea, Clear Lake NationalWildlife Refuge, and Honey Lake WildlifeArea were the only othersites that heldover 1000 pairsof CaliforniaGulls. In mostyears, Butte Valley, Clear Lake, Big Sage Reservoir,and Honey Lake togetherheld over 98% of the state'sbreeding Ring-billed Gulls; Goose Lake held9% in 1997. Muchof the historicalrecord of gullcolonies consists of estimatestoo roughfor assessmentof populationtrends. Nevertheless, California Gulls, at least,have increased substantially in recentdecades, driven largely by trendsat Mono Lake and San FranciscoBay (first colonizedin 1980). Irregularoccupancy of some locationsreflects the changing suitabilityof nestingsites with fluctuatingwater levels.In 1994, low water at six sites allowedcoyotes access to nestingcolonies, and resultingpredation appeared to reducenesting success greatly at threesites. Nesting islands secure from predators and humandisturbance are nestinggulls' greatest need. Conover(1983) compileddata suggestingthat breedingpopulations of Ring-billed(Larus delawarensis)and California(Larus californicus)gulls haveincreased greafiy in the Westin recentdecades. Detailed assessments of populationstatus and trends of these speciesin individualwestern states, however,have been publishedonly for Washington(Conover et al. -

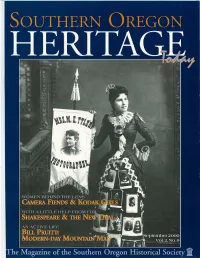

Link to Magazine Issue

----.. \\U\.1, fTI!J. Shakespeare and the New Deal by Joe Peterson ver wonder what towns all over Band, William Jennings America would have missed if it Bryan, and Billy Sunday Ehadn't been for the "make work'' was soon reduced to a projects of the New Deal? Everything from walled shell. art and research to highways, dams, parks, While some town and nature trails were a product of the boosters saw the The caved-in roofof the Chautauqua building led to the massive government effort during the decapitated building as a domes' removal, andprompted Angus Bowmer to see 1930s to get Americans back to work. In promising site for a sports possibilities in the resulting space for an Elizabethan stage. Southern Oregon, add to the list the stadium, college professor Oregon Shakespeare Festival, which got its Angus Bowmer and start sixty-five years ago this past July. friends had a different vision. They "giveth and taketh away," for Shakespeare While the festival's history is well known, noticed a peculiar similarity to England's play revenues ended up covering the Globe Theatre, and quickly latched on to boxing-match losses! the idea of doing Shakespeare's plays inside A week later the Ashland Daily Tidings the now roofless Chautauqua walls. reported the results: "The Shakespearean An Elizabethan stage would be needed Festival earned $271, more than any other for the proposed "First Annual local attraction, the fights only netting Shakespearean Festival," and once again $194.40 and costing $206.81."4 unemployed Ashland men would be put to By the time of the second annual work by a New Deal program, this time Shakespeare Festival, Bowmer had cut it building the stage for the city under the loose from the city's Fourth ofJuly auspices of the WPA.2 Ten men originally celebration. -

Volcanic Legacy

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacifi c Southwest Region VOLCANIC LEGACY March 2012 SCENIC BYWAY ALL AMERICAN ROAD Interpretive Plan For portions through Lassen National Forest, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Tule Lake, Lava Beds National Monument and World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................4 Background Information ........................................................................................................................4 Management Opportunities ....................................................................................................................5 Planning Assumptions .............................................................................................................................6 BYWAY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................................7 Management Goals ..................................................................................................................................7 Management Objectives ..........................................................................................................................7 Visitor Experience Goals ........................................................................................................................7 Visitor -

Water Allocation in the Klamath Reclamation Project (Oregon State

Oregon State University Extension Service Special Report 1037 December 2002 Water Allocation in the Klamath Reclamation Project, 2001: An Assessment of Natural Resource, Economic, Social, and Institutional Issues with a Focus on the Upper Klamath Basin William S. Braunworth, Jr. Assistant Extension Agriculture Program Leader Oregon State University Teresa Welch Publications Editor Oregon State University Ron Hathaway Extension agriculture faculty, Klamath County Oregon State University Authors William Boggess, department head, Department of William K. Jaeger, associate professor of agricul- Agricultural and Resource Economics, Oregon tural and resource economics and Extension State University agricultural and resource policy specialist, Oregon State University William S. Braunworth, Jr., assistant Extension agricultural program leader, Oregon State Robert L. Jarvis, professor of fisheries and University wildlife, Oregon State University Susan Burke, researcher, Department of Agricul- Denise Lach, codirector, Center for Water and tural and Resource Economics, Oregon State Environmental Sustainability, Oregon State University University Harry L. Carlson, superintendent/farm advisor, Kerry Locke, Extension agriculture faculty, University of California Intermountain Research Klamath County, Oregon State University and Extension Center Jeff Manning, graduate student, Department of Patty Case, Extension family and community Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University development faculty, Klamath County, Oregon Reed Marbut, Oregon Water Resources -

Upper Klamath Basin, Tule Lake Subbasin • Groundwater Basin Number: 1-2.01 • County: Modoc, Siskiyou • Surface Area: 85,930 Acres (135 Square Miles)

North Coast Hydrologic Region California’s Groundwater Upper Klamath Groundwater Basin Bulletin 118 Upper Klamath Basin, Tule Lake Subbasin • Groundwater Basin Number: 1-2.01 • County: Modoc, Siskiyou • Surface Area: 85,930 acres (135 square miles) An important note on the status of the groundwater resources in the Tule Lake Subbasin, is that, historically, groundwater use in the basin has been relatively minor. Since about 1905, when the Bureau of Reclamation began building the Klamath Project to provide surface water to agriculture on reclaimed land in the Klamath Basin, abundant surface water supplies have been available. In the 2001 Klamath Project Operation, water requirements for two sucker fish species in the upper basin and the coho salmon in the lower basin led the USBR to reduce surface water deliveries to the farmers to 26 percent of normal. The already existing drought conditions were further exacerbated by the operational drought. In 2001, drought emergencies were declared for the Klamath Basin by the governors of both California and Oregon. Governor Davis called upon California’s legislature to fund an Emergency Well Drilling Program in the Tulelake Irrigation District (TID). The governor also requested funding for a Hydrogeologic Investigation to evaluate new and future groundwater development. The emergency measures were taken because the TID had no alternate water supply for the nearly 75,000 acres in the district and farmers were faced with economic disaster. Ten large-capacity irrigation wells were constructed within the irrigation district for the emergency program. Four of the ten wells produce 10,000 gpm and greater. The lowest yielding well produces 6,000 gpm. -

Historical Evidence

Distribution of Anadromous Fishes in the Upper Klamath River Watershed Prior to Hydropower Dams— A Synthesis of the Historical Evidence fisheries history Knowledge of the historical distribution of anadromous fish is important to guide man- agement decisions regarding the Klamath River including ongoing restoration and regional recovery of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). Using various sources, we determined the historical distribution of anadromous fish above Iron Gate Dam. feature Evidence for the largest, most utilized species, Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus ABSTRACT tshawytscha), was available from multiple sources and clearly showed that this species historically migrated upstream into tributaries of Upper Klamath Lake. Available infor- mation indicates that the distribution of steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) extended to the Klamath Upper Basin as well. Coho salmon and anadromous lamprey (Lampetra tri- dentata) likely were distributed upstream at least to the vicinity of Spencer Creek. A population of anadromous sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) may have occurred historically above Iron Gate Dam. Green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris), chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), coastal cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki clarki), and eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus) were restricted to the Klamath River well below Iron Gate Dam. This synthesis of available sources regard- ing the historical extent of these species’ upstream distribution provides key information necessary to guide management and habitat restoration efforts. Introduction John B. Hamilton Gary L. Curtis Gatschet’s statement is that salmon ascend the Klamath river twice a year, in June and again in autumn. This is in agreement with my information, that the run comes in the middlefinger Scott M. Snedaker month [sic], May–June, and that the large fish run in the fall...They ascend all the rivers David K. -

Relative Dating and the Rock Art of Lava Beds National Monument

RELATIVE DATING AND THE ROCK ART OF LAVA BEDS NATIONAL MONUMENT Georgia Lee and William D. Hyder University of California, Los Angeles University of California, Santa Barbara ABSTRACT Dating rock art has long been a serious impediment to its use in archaeological research. Two rock art sites in Lava Beds National Monument present an unusual opportunity for the establishment of a relative dating scheme tied to external environmental events. In the case of Petroglyph Point, extended wet and dry climatic cycles produced changes in the levels of Tule Lake that successively covered, eroded, and then exposed the petroglyph bearing surfaces. Similarly, wet periods would have precluded painting at the nearby Fern Cave as the cave walls would have been too wet for paint to bond to the wall. The study of past climatic conditions, coupled with other archaeological evidence, allows us to present a model from which a relative chronology for Modoc rock art of Northeastern California covering the past 5,000 years can be constructed. INTRODUCTION Lava Beds National Monument is located in northeastern California, south of Klamath Falls, Oregon. Aside from a very interesting history that encompasses the Modoc Indians (and their predecessors) and the famous Modoc Wars of 1872-73, the Monument has numerous natural geological features of interest, as well as some outstanding rock art sites. It is also on the migratory bird flyway, making it a popular area for hunters and bird watchers alike. During World War II a Japanese internment camp was located nearby. These various attractions serve to draw a number of visitors to the Monument throughout the year. -

From the Editors Trail Turtles Head North

Newsletter of the Southwest Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association January, 2005 From the Editors Trail Turtles Head North In this newsletter we give the The SWOCTA Trail Turtles report of the SWOCTA Trail Turtles‟ played hooky from the southern trails Fall 2004 trip on the Applegate Trail. this fall. Don Buck and Dave Hollecker The Turtles made extensive use of the offered to guide the Turtles over the recently published Applegate Trail Applegate Trail from Lassen Meadows Guide (see the advertisement on the back to Goose Lake. In a way, it could be said cover of this issue). The Turtles felt that we were still on a southern trail, as “appreciation for those who … have the Applegate Trail was also known as spent long hours researching and finding the Southern Trail to Oregon when it … this trail that [has] been waiting to first opened. again be part of the … historical record.” After learning of the ruggedness We hope that the Turtles‟ ongoing of the trip, and with the knowledge there efforts to map the southwestern emigrant would be no gas, food or ice for 300 trails also will lead to a guidebook, for miles, everyone loaded up appropriately. which future users will feel a similar The number of vehicles was limited to appreciation. eight to facilitate time constraints and We (the “Trail Tourists”) also lack of space in some parking and include a record of our recent trip to camping areas. Fourteen people explore the Crook Wagon Road. attended. Unfortunately, we received our copy of the new guidebook, General Crook Road in Arizona Territory, by Duane Hinshaw, only after our trip. -

The Story of Susan's Bluff and Susan

A Working Organization Dedicated to Marking the California Trail FALL 2011 The Story of Susan’s Bluff and Susan Story by Denise Moorman Photos by Jim Moorman and Larry Schmidt It’s 1849 on the Carson Trail. Emigrant wagon trains and 49ers are winding their way through the newly acquired Upper California territory (western Nevada) on their way to the goldfields, settlements and cities of California. One of the many routes through running through this area follows along the Carson River between the modern Fort Churchill Historic Site and the town of Dayton. Although not as popular as the faster Twenty-Six Mile Desert cutoff, which ran roughly where U.S. Highway 50 goes today, the Carson River route provided valuable feed and water for the stock the New Trails West Marker, CR-20 at Susan’s Bluff. pioneers still had. Along this route the wagon trains hugged the left bank of the Carson until they Viewed from the direction the emigrants were reached a steep bluff jutting out almost to the river. approaching, the bluff hides behind other ridges Although foot traffic could make it around the point until you are past it. However, looking back, it of the bluff, wagons had to ford the river before they looms powerfully against the sky. This makes one reached it. Trails West recently installed the last wonder how something so imposing came to be Carson Route marker, Marker CR-20, near this ford known as “Susan’s Bluff?” continued on page 4 at the base of the cliff known as Susan’s Bluff. -

A Habitat Management Alternative for Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge

FARM/WETLAND ROTATIONAL MANAGEMENT - A HABITAT MANAGEMENT ALTERNATIVE FOR TULE LAKE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE INTRODUCTION Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) is located in extreme Northern California in Modoc and Siskiyou Counties approximately 6 miles west of the town of Tulelake, California.The refuge is one of 6 refuges within the Klamath Basin NWR complex. Historic Tule Lake fluctuated widely from >100,000 acres (1890) to 53,000 acres (1846) (Abney 1964).Record highs and lows for the lake were undoubtably greater before written records were kept. High water marks on surrounding cliffs indicate levels 12 feet higher than the 1890 records (Abney 1964).These extremes of water level were the key to maintaining the high aquatic productivity of this ecosystem.The historic lake was bounded on the north and west by vast expanses of tule marshes which supported tremendous populations of colonial nesting waterbirds and summer resident and migratory waterfowl. In 1905, the states of Oregon and California ceded to the United States the lands under both Tule and Lower Klamath lakes.In that same year, the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) tiled Notice of Intention to utilize all unappropriated waters of the Klamath Basin (Pafford 1971) and ultimately the Klamath Project was approved.As part of the Klamath Project, the Clear Lake dam was completed in 19 10 and the Lost River diversion was completed in 1912. The Clear Lake dam was intended to store water in the Lost River basin for irrigation and the Lost River Diversion routed water directly to the Klamath River thus removing the major source of water to Tule Lake.As a result to these actions, Tule Lake receded in size.