Gippsland Regional Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Rainforest Mapping in Victoria 2018 - Extent and Type

Primary Rainforest Mapping in Victoria 2018 - extent and type Matt White, Khorloo Batpurev, Owen Salkin and Graeme Newell May 2019 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 309 Acknowledgment We acknowledge and respect Victorian Traditional Owners as the original custodians of Victoria's land and waters, their unique ability to care for Country and deep spiritual connection to it. We honour Elders past and present whose knowledge and wisdom has ensured the continuation of culture and traditional practices. We are committed to genuinely partner, and meaningfully engage, with Victoria's Traditional Owners and Aboriginal communities to support the protection of Country, the maintenance of spiritual and cultural practices and their broader aspirations in the 21st century and beyond. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.ari.vic.gov.au Citation White, M., Bhatpurev, K., 1Salkin, O. and Newell G. (2019). Primary Rainforest Mapping in Victoria 2018 - extent and type. Arthur Rylah Institute Technical Report Series No. 309. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria. 1 Natural Systems Analytics Front cover photo Warm Temperate Rainforest Goolengook Forest Block, Errinundra National Park, East Gippsland (Matt White). © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. -

Cool Temperate Mixed Forest Investigation Report

INVESTIGATION REPORT COOL TEMPERATE RAINFOREST & MIXED FOREST RAINFOREST SITE OF SIGNIFICANCE (EG85 - Hensleigh - Far Creek) COAST RANGE ROAD VicForests Logging coupe 886-509-0012 Abstract Sections of VicForests scheduled logging coupe 886-509-0012 were investigated to assess the presence and extent of Cool Temperate Rainforest and Cool Temperate Mixed Forest communities. Areas of Cool Temperate Rainforest were identified within coupe 886-509-0012. These areas of the study location were readily identified by the presence of rainforest character species and the comparative structural composition of these stands to those expected to be found in mature rainforest. Cool Temperate Mixed Forest (Mixed Forest) areas of the study location within coupe 886-509- 0012 were identified by noting the presence of characteristic Mixed Forest species including in their formation of a multi-layer structured community comprised of Mixed Forest character species of an advanced age class, the presence of cool temperate rainforest character and differential species, and the topographic contiguity and relative proximity between the Mixed Forest areas within coupe 886-509- 0012 and the extant Mixed Forest clearly identifiable in the adjacent forest areas immediately to the north of coupe 886-509-0012 across Coast Range Road in the Errinundra National Park. This investigation also notes that coupe 886-509-0012 is located within a “Rainforest Site of Significance” (EG85 - Hensleigh - Far Creek). Recommendations are made to the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) and to VicForests to ensure that all areas of Cool Temperate Rainforest and Mixed Forest are excluded from logging and that no further logging is undertaken within the “Rainforest Site of Significance”. -

Gippsland Roadmap

9 Dec 2019 The Energy Innovation Foreword Co-operative1, which has 10 years of experience On behalf of the Victorian Government, I am pleased to present the Victorian Regional Renewable Energy Roadmaps. delivering community-based As we transition to cleaner energy with new opportunities for jobs and greater security of supply, we are looking to empower communities, accelerate renewable energy and build a more sustainable and prosperous energy efficiency and state. renewable energy initiatives in Victoria is leading the way to meet the challenges of climate change by enshrining our Victorian Renewable Energy Targets (VRET) into law: 25 per the Southern Gippsland region, cent by 2020, rising to 40 per cent by 2025 and 50 per cent by 2030. Achieving the 2030 target is expected to boost the Victorian economy by $5.8 billion - driving metro, regional and rural industry and supply chain developed this document in development. It will create around 4,000 full time jobs a year and cut power costs. partnership with Community It will also give the renewable energy sector the confidence it needs to invest in renewable projects and help Victorians take control of their energy needs. Power Agency (community Communities across Barwon South West, Gippsland, Grampians and Loddon Mallee have been involved in discussions to help define how Victoria engagement and community- transitions to a renewable energy economy. These Roadmaps articulate our regional communities’ vision for a renewable energy future, identify opportunities to attract investment and better owned renewable energy understand their community’s engagement and capacity to transition to specialists)2, Mondo renewable energy. -

National Parks Authority

1970 VICTORIA REPORT OF THE NATIONAL PARKS AUTHORITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30rH JUNE, 1968 Ordered by the Legislative Assembly to be printed, 15th September, 1970. By At~thority: C. H. RIXON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 22.-7938/70.-PRICB 40 cents. NATIONAL PARKS AUTHORITY TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30th JUNE, 1968 To the Honorable Sir Henry Bolte, K.C.M.G., M.L.A., Premier of Victoria, Melbourne, 3002. SIR, In accordance with the requirements of Section 15 of the National Parks Act 1958 (No. 6326), the Authority has the honour to submit to you for presentation to Parliament, its Twelfth Annual Report covering its activities for the year ended 30th June, 1968. THE AUTHORITY. The membership of the National Parks Authority during the year under review was as follows:- Chairman : The Honorable J. W. Manson, M.L.A., Minister of State Development. Deputy C~airman : J. H. Aldred, F.R.I.P.A. Members: A. J. Holt, Secretary for Lands ; A. 0. P. Lawrence, B.Sc. (Adel.), Dip. For. (Oxon.), Dip. For. (Canberra), Chairman, Forests Commission of Victoria; R. G. Downes, M.Agr.Sc., F.A.I.A.S., Chairman, Soil Conservation Authority; A. Dunbavin Butcher, M.Sc. (Melb.), Director of Fisheries and Wildlife; Dewar W. Goode, representing organizations concerned with the protection of native fauna and flora ; G. M. Pizzey, representing persons having a special interest in national parks ; E. H. R. Burt, representing the Victorian Ski Association ; G. E. Hindle, representing the Victorian Government Tourist Bureau ; L. H. Smith, M.Sc., D.Phil. -

Accessible Gippsland Inspiring Visitor Experiences

ACCESSIBLE GIPPSLAND INSPIRING VISITOR EXPERIENCES inspiredbygippsland.com.au explore, experience GIPPSLAND’S and enjoy REGIONS Victoria’s parks VICTORIA GIPPSLAND Victoria’s parks are more accessible than ever. Wilsons Promontory National Park and Cape Conran Coastal Park now have accommodation and equipment to make it easier for people with Just an hour’s easy drive east of Melbourne a disability and their families and carers to enjoy you will begin to experience the beauty of their stay. Gippsland. There are few places in the world Cabins are equipped with ramps, electric high low where you will find such an extraordinary beds and accessible bathrooms. A personal hoist diversity of landscapes. From snow-capped is also available free of charge. mountains to lush rolling hills, rugged Be Inspired by Gippsland’s coastlines and wide sandy beaches, there is Visitors can also use all-terrain wheelchairs to access something to inspire us all. the stunning beaches or the parks’ spectacular diverse range of accessible trails. These are also available at the Grampians For visitor information visit and Point Nepean National Parks. visitor experiences and inspiredbygippsland.com.au To plan your next park adventure call Parks Victoria accommodation options. Visitor Information Centre locations and on 13 1963 or visit www.parks.vic.gov.au and phone numbers can be found on the final search by park. pages of this brochure. 2 | inspiredbygippsland.com.au Gippsland boasts a diverse range of accessible visitor experiences that are Great Alpine Rd welcoming and inclusive of Omeo people of all ages and abilities, Sydney people with a disability, seniors and parents with young children. -

Electronic Gaming Machines Strategy 2015-2020

Electronic Gaming Machines Strategy 2015-2020 Version: 1.1 Date approved: 22 December 2015 Reviewed: 15 January 2019 Responsible Department: Planning Related policies: Nil 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................. 3 2 Definitions ............................................................................................................. 3 3 Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 5 4 Scope .................................................................................................................... 5 5 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 6 Gambling and EGMs in the City of Casey ........................................................... 6 7 City of Casey Position on Electronic Gaming Machines ................................... 7 7.1 Advocacy & Partnerships ....................................................................................... 7 7.2 Local Economy ....................................................................................................... 8 7.3 Consultation & Information Provision ...................................................................... 9 7.4 Community Wellbeing ............................................................................................ 9 7.5 Planning Assessment .......................................................................................... -

Dissonance Surrounding the Aboriginal Origin of a Selection of Placenames in Victoria, Australia: Lessons in Lexical Ambiguity

14. Dissonance surrounding the Aboriginal origin of a selection of placenames in Victoria, Australia: Lessons in lexical ambiguity Ian D. Clark Federation University Australia When studying the history of some 3,400 Aboriginal toponyms in Victoria, Australia, the majority of placenames were found to have no equivocalness or ambiguity about them (Clark and Heydon 2002). Although it was not possible to find meanings for every one of these Aboriginal placenames, in terms of historical accounts and folk etymology there was no ambiguity – the vast majority of the placenames are accepted in the source material as being of Aboriginal origin. This paper concerns some 26 placenames for which there is dissonance or a lack of agreement about whether or not they are Aboriginal in origin. These names are considered in some detail in an effort to resolve their lexical ambiguity and an attempt is made to explain the reasons for the ambiguity and to find any patterns and causal factors. The merits of the claims and counter claims in each case will be examined and an attempt made to categorise the assertion of Aboriginal etymology as either grounded in the historical evidence, or likely to be explained by folk etymology – that is, a false meaning based on its structure or sound that may lack historical basis but has been accepted through common practice, or explained as a false etymology that neither accords with historical evidence nor equates with folk etymologies. A critical issue when considering toponymic etymology is the fragility of toponymic knowledge and the concomitant difficulty of learning about the origins of placenames. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

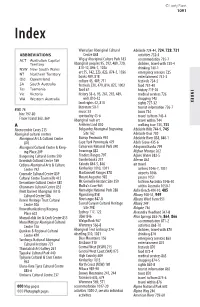

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Eligible Schools – South Eastern Victoria

ELIGIBLE SCHOOLS – SOUTH EASTERN VICTORIA Category 1 Schools Airly PS Drouin South PS Lindenow South PS Noorinbee PS Swifts Creek P-12 School Alberton PS Drouin West PS Loch PS Nowa Nowa PS Tambo Upper PS Araluen PS Eagle Point PS Loch Sport PS Nungurner PS Tanjil South PS East Gippsland Specialist Bairnsdale PS School Longford PS Nyora PS Tarwin Lower PS Bairnsdale SC Ellinbank PS Longwarry PS Omeo PS Tarwin Valley PS Bairnsdale West PS Fish Creek and District PS Lucknow PS Orbost North PS Thorpdale PS Boisdale Consolidated School Foster PS Maffra PS Orbost PS Toora PS Goongerah Tubbut P–8 Bona Vista PS College Maffra SC Orbost SC Toorloo Arm PS Briagolong PS Gormandale And District PS Mallacoota P-12 College Paynesville PS Trafalgar High School Bruthen PS Guthridge PS Marlo PS Perseverance PS Trafalgar PS Buchan PS Heyfield PS Metung PS Poowong Consolidated School Warragul & District Specialist School Buln Buln PS Jindivick PS Mirboo North PS Rawson PS Warragul North PS Bundalaguah PS Kongwak PS Mirboo North SC Ripplebrook PS Warragul PS Cann River P-12 College Korumburra PS Nambrok Denison PS Rosedale PS Warragul Regional College Clifton Creek PS Korumburra SC Narracan PS Sale College Welshpool and District PS Cobains PS Labertouche PS Neerim District Rural PS Sale PS Willow Grove PS Cowwarr PS Lakes Entrance PS Neerim District SC Sale Specialist School Woodside PS Dargo PS Lakes Entrance SC Neerim South PS Seaspray PS Wurruk PS Darnum PS Lardner and District PS Newmerella PS South Gippsland SC Yarragon PS Devon North PS Leongatha PS -

Dry Seasonal Conditions in Rural Victoria

Department of Primary Industries Dry Seasonal Conditions in Rural Victoria Report: 51 September 22, 2005 Environmental Indicators Rainfall August rainfall totals were close to normal. Over winter as a whole, rainfall was somewhat above normal in the North East and in East Gippsland, somewhat below normal in Central Victoria and in West Gippsland, and near to normal elsewhere. August had a warm spell at the end of the month following the widespread snow on the 10th. Overall daytime temperatures were 1°C above average and nightime temperatures were about average. For the 6-month period from March to August, serious to severe rainfall deficiencies extend from the far southeast of South Australia across southwest and south-central Victoria to west Gippsland. The deficiencies over southern Victoria are not as extensive or intense as they were at the end of July. The most significant rainfall in September occurred through the second week and varied from 0-5 mm in the north west to over 100 mm in pockets of the North East (Figure 1). The seasonal rainfall outlook for October to December indicates an increased likelihood of below median falls over parts of southern Victoria for the December quarter. Chances of above median rainfall are between 30 and 40% in a band extending from the far southeast of South Australia to West Gippsland. This includes most of the areas that have suffered severe short-term rainfall deficiencies since the start of autumn, and a general downturn in rainfall since the mid 1990s. The chances of a wetter than average season are between 40 and 50% over the rest of the State. -

SCRATCH ‘N’ SNIFF Issue 46- OCTOBER 2017 CLUB ESTABLISHED: 1979 - VCA AFFILIATED: 1986

SCRATCH ‘N’ SNIFF Issue 46- OCTOBER 2017 CLUB ESTABLISHED: 1979 - VCA AFFILIATED: 1986 Paralysis Ticks in Wellington Shire – Longford Veterinary Centre UPCOMING EVENTS SATURDAY 14th & SUNDAY 15th OCTOBER 2017 - Agility & Jumping Trial SUNDAY 10th DECEMBER 2017 - Christmas Break up SUNDAY 4th FEBRUARY 2018 - First Sunday for Club in 2018 As the weather warms up we are coming into tick season. The tick that causes us problems locally is the southern paralysis tick, Ixodes cornuatus. This tick occurs throughout the shire but our 'hot spots' are Paradise Beach and Golden Beach. Basically if your visiting anywhere from Longford back to the coast your pet should be on year round tick prevention. At Longford Veterinary Centre we treat several cases of dogs affected by tick paralysis every year. The paralysis tick feeds on the blood of the pet and its' saliva is a toxin. The tick toxin causes an ascending paralysis, which means paralysis starts in the back legs and moves upwards. This may eventually cause death due to paralysis of the respiratory muscles. Tick paralysis can be treated successfully if you realise that your dog is affected early enough. We provide intravenous fluids, various supportive therapies and treat with tick antiserum (similar to the concept of treating snake bite with anti-venom). It is far better to have dogs on prevention. There are several options however we favour the monthly or 3 monthly tablets as these are waterproof and hence ideal for dogs going to the beach! It is possible to still find ticks on dogs on some tick preventative products- the tick attaches, feeds and then dies. -

Water Research Laboratory

Water Research Laboratory Never Stand Still Faculty of Engineering School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment WRL Technical Report 2017/09 October 2017 by I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Project Details Report Title Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment Report Author(s) I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Report No. 2017/09 Report Status Final Date of Issue 16 October 2017 WRL Project No. 2014105.01 Project Manager Ian Coghlan Client Name 1 Umwelt Australia Pty Ltd Client Address 1 75 York Street PO Box 3024 Teralba NSW 2284 Client Contact 1 Pam Dean-Jones Client Name 2 Eurobodalla Shire Council Client Address 2 89 Vulcan Street PO Box 99 Moruya NSW 2537 Client Contact 2 Norman Lenehan Client Reference ESC Tender IDs 216510 and 557764 Document Status Version Reviewed By Approved By Date Issued Draft J T Carley G P Smith 9 June 2017 Final Draft J T Carley G P Smith 1 September 2017 Final J T Carley G P Smith 16 October 2017 This report was produced by the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales for use by the client in accordance with the terms of the contract. Information published in this report is available for release only with the permission of the Director, Water Research Laboratory and the client. It is the responsibility of the reader to verify the currency of the version number of this report.