Community Health Needs Assessment As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Pollution in Boston's Chinatown and Income Disparity

Air pollution in Boston’s Chinatown and Income Disparity Introduction Income Cluster surrounding Chinatown with Major roads and highways Conclusion It is Chinatown’s unique position that puts it in danger to be engulfed by Boston’s Chinatown is the third largest in gentrification and displacement. As seen in the center map Chinatown is the United states, and like many Boston a low-high outlier in an income cluster analysis, meaning that it is a low- neighborhoods build on top of a landfill. Due income area surrounded by high income neighborhoods. Accentuated by to developing railways the area became less the proximity to highways and major roads Chinatown is exceptionally desirable to earlier immigrants of mostly Jew- vulnerable to high levels of air pollution. Many studies show that higher ish, Irish, and Italian descent. Chinese laborers levels of air pollution is associated with higher levels of asthma as well as started to settle on the area starting from the mid 1800’s. Initially Chinese possible increase in cardiovascular diseases. Awareness becomes highly exclusion act of 1882 limited the growth of the area, however after World important, and community involvement becomes a necessity in order to War II when the act was lifted, this area started to boom with new incom- preserve Boston’s historic Chinatown. Studies show communities of color ing Chinese immigrants. 1950’s saw the construction of Central Artery are more concerned with air pollution and expect which in return saw many families displaced from the area that had be- more out of the government to have more involve- come the Chinatown. -

2018 Carney Community Health Needs Assessment

Community Health Needs Assessment 2018 This page intentitionally left blank Table of Contents Acknowledgments 4 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 6 Methods 7 Findings 8 Demographics 9 Chronic Disease 20 Mental Health 29 Substance Use Disorder 32 Housing Stability 38 Recommendations 46 Limitations 54 Appendix A. Supplemental Health Indicators and Demographic Data 55 Appendix B. Key Informant Survey 59 Appendix C. Focus Group Questions 60 References 61 3 | Page Acknowledgements This Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) was made possible through the cooperative support of several individuals and organiZations. We are particularly grateful for the Community Benefits leadership at Carney Hospital, Krisha Cowen, Marketing Manager and Barbara CouZens, Community Relations & Patient Advocacy Manager. A special thank you to our community partners: Bethel AME Church, Morning Star Baptist Church, Talbot Norfolk Triangle, Norine Woods – Community member, The Boston Project Ministries, Community Care Alliance at Carney, Four Corners Main Street, Big City Radio, Francine Pope – Former Boston probation officer, and Codman Square NDC, among many others who also provided feedback through survey responses and comments. Thank-you to Paul Oppedisano, Accreditation Coordinator/Director MassCHIP, Office of the Commissioner, Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Lastly, we thank the team at H&HS Consulting Group LLC. that produced this body of work. Sincere acknowledgements to Paulo Gomes, MSHS, Principal Consultant, Benjamin Ethier, Public Health Research Assistant, Kristy Najarian, MPH, Data Analyst, Jennifer Hohl, MPH, Data Entry. 4 | Page Executive Summary This report is a comprehensive analysis of health indicators for Carney Hospital. The Carney Hospital service area includes Dorchester (02122), Dorchester (02124), Dorchester (02125), Mattapan, South Boston, Hyde Park, Braintree, Milton, and Quincy. -

Harvard Plans Its Sizable Allston Future

Forging a Connection with immigrants and literacy PAGE6 ~ Community Newspaper Company Ill www.allstonbrightontab.com FRIDAY, OCTOBER 24, 2003 Vol. 8, No. 12 Iii 52 Pages Ill 3 Sections 75¢ New fashions Harvard plans its sizable Allston future By Jill Casey STAFF WRITER "I for one don't want his week Harvard Uni versity released its broad Allston to be just T vision for the next phase student housing and of development in Allston. The long-awaited statement did not nothing more. I want offer too many specifics, but did the academic uses and give indication that they hope to transfer many of its integral aca bio-tech and medical demic programs across the research. I think the Charles River to Allston. 'This is a critical time in Har life sciences are the vard's history, as it is for all high future for much of er education .... At such a time, the properties Harvard has acquired Allston Landing." in Allston afford us a historic op portunity to innovate, to grow City Councilor and to build our long-term acade Jeny McDennott mic strength, while also con tributing to the vitality of our im With more than 200 acres of portant home communities," said property holdings that they have Harvard University President PHOTO ev ZAAA TZANEV acquired in Allston since the Last week, many people ventured from watchln# the Red Sox at home t o watching the Models from Maggie Inc. show the latest Lawrence Summers in an open fashions at Saks 5th Avenue at Tonic - the Mel L,ounge In Brighton. -

Referral List / Listado De Referencias / Lista De Recomendação

Referral List / Listado de Referencias / Lista de Recomendação For immigration assistance please contact the following providers Para asistencia de inmigración, por favor comunicarse con los siguientes proveedores Para assistência sobre imigração, favor contactar os seguintes provedores de serviços BOSTON Mayor’s Office for Immigrant Advancement Action for Boston Community Development, Inc. (Consultations: 1st & 3rd Wednesday of the month, 12-2pm) 21 Meridian St. East Boston, MA 02128 // 617-567-8857 1 City Hall Sq., Room 806, Boston, MA 02201 // 617-635- 2980 30 Bickford St. Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 // 617-522-4250 714 Parker St. Roxbury, MA 02120 // 617-445-6000 Political Asylum/Immigration Representation Project * 535 River St. Mattapan, MA 02126 // 617-298-2045 98 N. Washington St. Boston, MA 02114 // 617-742-9296 554 Columbus Ave. Boston, MA 02118// 617-267-7400 Project Citizenship * Agencia ALPHA (Citizenship assistance only) 62 Northampton St., 1st Fl. (H-101), Boston, MA 02118 // 617-522- 4 Faneuil S Market Bldg., 3rd Fl., Boston 02109 // 617-694-5949 6382 East Boston Branch at Igleisa NuevaVida: Student Immigrant Movement (SIM)* 70 White St. East Boston, MA 02128 // 617-522-6382 9A Hamilton Pl., Boston MA 02108 // [email protected] American Civil Liberties Union – MA* Somali Development Center/African Social Services 211 Congress St., 3rd Fl., Boston, MA 02110 // 617-482-3170 10 Malcolm X Blvd., 2nd Fl., Boston, MA 02119 // 617-522- 0700 Asian American Civic Association Refugee and Immigrant Assistance Center 87 Tyler St., 5th Fl., Boston, MA 02111 // 617-426-9492 253 Roxbury St. Boston, MA 02119//617-238-2430 Asian Outreach Unit: Greater Boston Legal Services Victim Rights Law Center* 197 Friend St. -

The-Mark Residences Ebrochure.Pdf

East Boston’s New Vantage Point -71.042123 42.369917 The Mark at DeNormandie Wharf is the newest luxury residential community on the East Boston waterfront, a neighborhood where past and future are coming together to forge exciting new experiences. Here you will find a collection of thoughtfully- appointed condominium homes in a breathtaking setting, where the water offers the perfect tonic for effortless living. Welcome to The Mark from LoPresti Park pier East Boston’s new vantage point. The Mark from the Harborwalk RESIDENCES WATER BROUGHT US HERE. IT BRINGS US STILL. Living room Step into your home, refreshingly arranged, with an undeniable sophistication. Expansive windows bathe spaces with sunlight, complementing a tastefully selected palette of materials and finishes. Here every homecoming is greeted with a gracious and welcoming feel. Living space LIVING WELL Master bedroom EAST BOSTON WELCOME TO EAST BOSTON There’s history in this neighborhood that dates back to the early 1800’s. For more than a century its waterfront was a busy port and industrial center, with factories, shipbuilding yards and warehouses lining its streets. Today, East Boston is one of the city’s most attractive enclaves. Its authentic character and community feel has attracted a new generation of residents, drawn to its convenient location, great ethnic cuisine, cultural and outdoor amenities, and sweeping views of the Boston skyline. TANTALIZING EATS & NEIGHBORHOOD FEELS The East Boston food scene is as eclectic and authentic as they come. From meat pies and Vietnamese chicken salad at KO Pies in the Shipyard to chilaquiles at Taquería Jalisco, delicious pizza from Santarpio’s — a neighborhood institution since 1903 — or shellfish towers and champagne at Reelhouse just a block away, the options and portions are plentiful. -

Service Fees

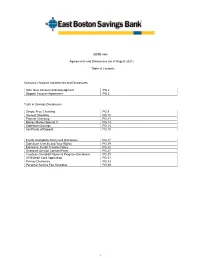

EBSB.com Agreements and Disclosures (as of August 2021) Table of Contents Consumer Account Agreements and Disclosures OAC New Account Acknowledgment PG.2 Deposit Account Agreement PG.3 Truth in Savings Disclosures Simple Free Checking PG.9 Interest Checking PG.10 Premier Checking PG.11 Money Market Special 3 PG.13 Statement Savings PG.14 Certificate of Deposit PG.15 Funds Availability Policy and Disclosure PG.17 Substitute Checks and Your Rights PG.19 Electronic Funds Transfer Policy PG.20 Overdraft Service Consent Form PG.27 Courtesy Overdraft Payment Program Disclosure PG.29 ATM/Debit Card Application PG.31 Privacy Disclosure PG.33 Personal Service Fee Schedule PG.39 1 NEW ACCOUNT ACKNOWLEDGEMENT IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT PROCEDURES FOR OPENING A NEW ACCOUNT: To help the government fight the funding of terrorism and money laundering activities, Federal law requires financial institutions to obtain, verify, and record information that identifies each person who opens an account. What this means for you: When you open an account, we will ask for your name, address, date of birth, and other information that will allow us to identify you. We may also ask to see your driver’s license or other identifying documents. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: All account holders authorize this institution to make inquiries from any consumer-reporting agency, including a check protection service, in connection with this account. ACCOUNT OPENING: All accounts approved through the automated account opening process are subject to final review and approval by the bank. Accounts will be considered open once we have received and approved all required account opening documentation and the account has been funded If the bank does not approve your account, the account will be closed and you will be mailed an Adverse Action form. -

HOLY NAME PARISH Email: [email protected] 1689 Centre Street, West Roxbury, MA 02132 Monday Through Friday 9:00Am-4:00Pm

Rectory: 617-325-4865, 617-325-5571 (fax) HOLY NAME PARISH Email: [email protected] 1689 Centre Street, West Roxbury, MA 02132 Monday through Friday 9:00am-4:00pm School: 617-325-9338, 617-325-7885 (fax) Admissions: 617-390-2374 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday-Friday, 8:00am to 3:00pm Early Childhood Center: 617-325-8669, 617-325-2146 (fax) www.holynameparish.com Online Giving with WeShare: https://holynameparish.churchgiving.com/ OUR MISSION STATEMENT Holy Name Parish is a family of believers aware of the saving power of the Holy Name of Jesus and the protection of the EVERYDAY STEWARDSHIP Mother of God. We are guided in our life’s journey by the wisdom of the Scriptures, the leadership of the Holy Father, the Recognize God in Your Ordinary Moments teachings of the Church, and nourished by the strength of the sacraments. Our concern about the needs of all our family Don’t Live a Lie One day, my son was explaining to members is deep and sincere, especially about the formation of youth. All this requires the effective cooperation of all his mother that he felt she had lied to him. It was members with the blessings of God. nothing very important, but he wanted to take this Rev. George P. Evans, Pastor opportunity to share how important telling the truth is Rev. Baldemar M. Garza, Parochial Vicar to him. He explained that he simply tells it like it is in Rev. Brian M. Flatley, In Residence all aspects of his life. But an hour later, we caught Rev. -

Residences on Morrissey Boulevard, 25 Morrissey Boulevard, Dorchester

NOTICE OF INTENT (NOI) TEMPORARY CONSTRUCTION DEWATERING RESIDENCES AT MORRISSEY BOULEVARD 25 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD DORCHESTER, MASSACHUSETTS by Haley & Aldrich, Inc. Boston, Massachusetts on behalf of Qianlong Criterion Ventures LLC Waltham, Massachusetts for US Environmental Protection Agency Boston, Massachusetts File No. 40414-042 July 2014 Haley & Aldrich, Inc. 465 Medford St. Suite 2200 Boston, MA 02129 Tel: 617.886.7400 Fax: 617.886.7600 HaleyAldrich.com 22 July 2014 File No. 40414-042 US Environmental Protection Agency 5 Post Office Square, Suite 100 Mail Code OEP06-4 Boston, Massachusetts 02109-3912 Attention: Ms. Shelly Puleo Subject: Notice of Intent (NOI) Temporary Construction Dewatering 25 Morrissey Boulevard Dorchester, Massachusetts Dear Ms. Puleo: On behalf of our client, Qianlong Criterion Ventures LLC (Qianlong Criterion), and in accordance with the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Remediation General Permit (RGP) in Massachusetts, MAG910000, this letter submits a Notice of Intent (NOI) and the applicable documentation as required by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for temporary construction site dewatering under the RGP. Temporary dewatering is planned in support of the construction of the proposed Residences at Morrissey Boulevard in Dorchester, Massachusetts, as shown on Figure 1, Project Locus. We anticipate construction dewatering will be conducted, as necessary, during below grade excavation and planned construction. The site is bounded to the north by the JFK/UMass MBTA red line station, to the east by William T. Morrissey Boulevard, to the south by paved parking associated with Shaw’s Supermarket, beyond which lies the Shaw’s Supermarket, and to the west by MBTA railroad tracks and the elevated I-93 (Southeast Expressway). -

Text Amendment Application No. 479 Cannabis Establishments Boston Planning and Development Agency

Text Amendment Application No. 479 Cannabis Establishments Boston Planning and Development Agency TEXT AMENDMENT NO. 432 THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS CITY OF BOSTON IN ZONING COMMISSION The Zoning Commission of the City of Boston, acting under Chapter 665 of the Acts of 1956, as amended, after due report, notice and hearing does hereby amend the text of the Boston Zoning Code, as established under Chapter 665 of the Acts of 1956, as amended, as follows: 1. By striking the definition "Medical Marijuana Treatment Center" from Articles 2 and 2A of the Code, and inserting in place thereof the following: "Cannabis Establishment," an entity, licensed and registered with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts that acquires, cultivates, possesses (including development of related products as edible marijuana infused products (MIP), tinctures, aerosols, oils, or ointments), transfers, transports, sells, distributes, dispenses, or administers cannabis, products containing cannabis, including, but not limited to an adult use cannabis establishment, a medical use cannabis establishment, a marijuana retailer, a marijuana product manufacturer or a marijuana cultivator. Cannabis Establishments shall include any Marijuana Establislunent or Medical Marijuana Treatment Center licensed pursuant to 935 CMR 500, 105 CMR 725.100, or any successor regulation. 2. By amending Article 8 (Regulation of Uses) as follows: a. In Section 8-7, Table A, Use Regulations, delete existing Use Item #39B "Medical Marijuana Treatment Center" and insert the following use item: SRHLBMIWMER 39B Cannabis Establishment F* F* F* C* C* C* C* C* C* C* 1 *Cannabis Establishment-provided that any cannabis establishment shall be sited at least one half mile or 2,640 feet from another existing cannabis establishment and at least 500 feet from a pre-existing public or private school providing education in kindergarten or any of grades 1 through 12. -

Boston Community Resources & Information

Boston Community Resources & Information Red Cross of Massachusetts 101 Station Landing Suite 510 Phone: (781) 410-3670 Phone: (800) 272-7337 (toll-free) Information Referral Services GET HELP WITH: Mental Health Assistance Financial Assistance Health Services Fuel & Utility Assistance: ABCD 178 Tremont Street Boston, MA 02111 Phone: (617) 348-6000 Services: Clothing and Essentials Housing Counseling Services Food Pantries LIST OF FOOD PANTRIES (Boston & Surrounding Areas) Dothouse Health – Food Pantry Every Wednesday morning for general public has a food pantry Requirement: Must live in Dorchester or surrounding towns Allston-Brighton NOC 640 Washington Street, Suite 203 Brighton, MA Call: 617.903.3640 Roxbury/N. Dorchester NOC 565 Warren Street Roxbury, MA 02121 Call: 617.442.5900 Jamaica Plain APAC 30 Bickford Street, Lower Level Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 Call: 617.522.4250 North End/West End NSC 1 Michelangelo Street Boston, MA 02113 Call: 617.523.8125 Parker Hill Fenway NSC 714 Parker Street Roxbury, MA 02120 Call: 617.445.6000 SNAP/South End NSC 554 Columbus Avenue Boston, MA 02118 Call: 617.267.7400 FREE MEALS AND SOUP KITCHENS: Bread and Jams 50 Quincy Street, Cambridge 617-441-3831 Call to make an appointment Boston Living Center 29 Stanhope Street, Boston 617-236-1012 Serves only individuals with HIV/AIDS Bring verification of HIV+ status and income verification Boston Rescue Mission / Pantry 39 Kingston Street, Boston 617-338-9000 Must be 18 years old A referral is needed, call to make an appointment CASPAR Emergency Service Center and Shelter 240 Albany Street, Cambridge 617-661-0600 Must be resident of Somerville or Cambridge, over age 18 Catholic Social Services (Fall River) 1600 Bay Street, Fall River 508-674-4681 Call for eligibility requirements Community Servings, Inc. -

New Bostonians Demographic Report

Mayor’s Office of New Bostonians Cheng Imm Tan, Director New Bostonians 2012 Research Division Alvaro Lima, Director 1 This report was prepared for the Mayor’s Office of New Bostonians by Mark Melnik and BRA Research Division staff, under the direction of Alvaro Lima, Director. Special thanks to Joshua Silverblatt for his invaluable role in creating this report. The information provided within this report is the best available at the time of its publication. City of Boston Thomas M. Menino, Mayor All or partial use of the data found within this report must be cited. Our preferred citation is as follows: Boston Redevelopment Boston Redevelopment Authority Authority/Research Peter Meade, Director Division, October 2012. Alvaro Lima, Director of Research 2 New Bostonians 2012 Table of Contents Demographics 4 Languages 15 Boston’s Neighborhood Diversity 22 Economic Contributions and Labor Force 31 English Proficiency 37 Educational Attainment 39 Homeownership 41 Citizenship 43 References 45 3 New Bostonians 2012 Demographics 4 39.3 Million Immigrants Live in the U.S. (2010) Immigrants account for more than 1 in 7 residents (12.8%), the highest percentage since 1930 (12%). 83.7% more immigrants live in the United States now than in 1990. Between 2000 and 2010, immigrants accounted for 50.3% of the nation’s population growth. In 2010, the nation’s largest immigrant groups were Latinos and Asians: 53% are from Latin America; 28% are from Asia; 12% are from Europe; 7% are from other regions in the world including Northern America and Oceania. 5 Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2008-2010. -

Michael Ulman Studio 32 Pinedale Road 617 325 9044 Roslindale, MA

Michael Ulman Studio 32 Pinedale Road 617 325 9044 Roslindale, MA 02131 www.michaelulman.com 617 694 6498 [email protected] EDUCATION June 2000 Northeastern University, Boston, MA College of Arts and Sciences Bachelor of Science in Art C O M M I S S I O N E D S C U L P T U R E I N S T A L L A T I O N S ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 2015 Sophia's Grotto Restaurant, Hyde Park, MA Steam Punk Wall Clock Private Residence, Wellesley, MA Exterior Curved Rain Canopes _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 2014 Private Residence, Arlington, MA Grape Arbor Structure _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 2013 Watermark II Apartment Building, Kendall Square, MA Seven Wall Bicycle Sculptures ____________________________________________________ FREELANCE DESIGN 2010 Kennedy Mitchell Miller Film Studio, Sydney, Australia –Designer Production and Fabrication Designer for Mad Max 4 Fury Road ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 2009 Northeastern University, Boston, MA – Wildwood Permanent Sculpture Collection Northeastern University, Boston, MA – Pterodactyl Permanent Sculpture Collection ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 2007 Northeastern University, Boston, MA – Green Permanent Sculpture Collection Northeastern University, Boston, MA – Design Husky Dog for Presidential