SPAN Mongolia – Terminal Evaluation Report I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2010 Far Horizons Newsletter

NEWSLETTER FAR HORIZONS ARCHAEOLOGICAL & CULTURAL TRIPS Volume 15, Number 1 • Spring 2010 Published Erratically by Far Horizons • P.O. Box 2546 • San Anselmo, CA 94979 USA (800) 552-4575 • (415) 482-8400 • fax (415) 482-8495 • www.farhorizons.com • email: [email protected] Dear Travelers, I am delighted to dedicate this newsletter to those participants who travel with Far Horizons repeatedly – thank you! In fact, we have included articles from some of our frequent travelers in which they eloquently describe their experiences exploring remarkable destinations with our fabulous study leaders. Don’t miss these evocative accounts of their adventures. There are only a very few spaces remaining on the September trip led by Professor Jonathan Phillips of History Channel fame. I am so pleased that people are excited about our Crusades trip! By the way, look for Professor Jonathan Phillips’ new book, Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades. We plan to design more itineraries relating to the medieval era, so keep watching our webpage. Are you a Bob Brier enthusiast (do you know anyone who isn’t!)? There are still a few spaces left on Bob’s Egypt in Rome May 10-20, 2010, and Oases of Egypt Oct 29 - Nov 15, 2010. Plus Bob Brier heads to Sudan in March of 2011. Be sure and read what former travelers have to say about Bob’s trips and register soon! With this newsletter we begin a new series written by Heather Stoeckley and Sara Barbieri, two members of the Far Horizons team who travel several times each year with our groups as tour manager. -

Sundowners Overland - Gobi Desert Explorer Page 1 of 6 Itinerary

Journey Itinerary Gobi Desert Explorer Days Westbound, Eastbound Countries Distance Activity level 16 Ulaanbaatar to Ulaanbaatar Mongolia 1,750 km Discover the very best of Mongolia, from the bustling capital Ulaanbaatar we journey across the steppe to Kharkhorin. We will encounter ancient Buddhist monasteries and the remarkable diversity of the Gobi Desert; sacred mountains, dinosaur ‘cemeteries’, flaming cliffs, singing sand dunes and spectacular canyons. Sundowners Overland - Gobi Desert Explorer Page 1 of 6 Itinerary Day 1: Ulaanbaatar Mongolia is the world’s most sparsely populated country with just 3 million people inhabiting the 1.5 million square kilometres of pristine desert, steppe and mountain. Almost half the population lives in its frenetic capital Ulaanbaatar where we will start our journey. Join your Tour Leader and fellow travellers on Day 1 at 5:00pm for your Welcome Meeting as detailed on your joining instructions. Meals - Day 1 – Dinner Day 2: To Bayangobi via Khustai National Park Beyond the city one million Mongolian’s still live a traditional nomadic or semi nomadic life and the horse is central to their existence. We visit the Gandan Monastery, with its huge gold Buddha, the spiritual home of the Mongolian people, before traveling to the Khustai National Park where wild horses, known as Tahki or Przewalski horses are bred and reintroduced to the wild. Once close to extinction, Takhi are the world’s only true wild horse. Mongolia is a country with such diverse landscapes and today we continue our way across the steppe to experience the uniqueness of the Bayangobi. Here we have the opportunity to hike in the stunning sand dunes that stretch over a distance of 80kms. -

Mongolia Exotic Tour

Mongolia Exotic Tour Key Information: Trip Length: 9 days/8 nights. Trip Type: Easy to Moderate. Tour Code: SMT-ORKHON-9D Specialty Categories: Adventure Expedition, Cultural Journey, Camel riding, Driving tour, Eco-Travel, Hiking, Hot spa, Local Culture, Nature & Wildlife. Meeting/Departure Points: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (excluding flights). Small Groups: 2-16 travelers-guaranteed! Best Season: Daily, June-September. Total Distance: about 2000kms/1243miles. Airfare or Train Included: No. Tour Customizable: Yes Tour Highlights: Upon your arrival in Ulaanbaatar, meet Samar Magic Tours team. Mongolia Exotic Tour takes you to the Natural Wonders of Central Mongolia. This journey designed especially for small groups, families, private, and funny travel. Exploration to Karakorum-the Genghis (Chinggis) Khan's 13th century capital, Orkhon Waterfall (also called Ulaan Tsutgalan)-this is perfect for swimming, fishing, short trekking and walks around the surrounding area, stop at VIII century Turkish monuments in the Orkhon Valley, Tsenkher Hot Spa and many more. Karakorum was the capital of the Mongol Empire in the 13th century and of the Northern Yuan in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in the north-western corner of the Ovorkhangai Province of Mongolia, near today's town of Kharkhorin, and adjacent to the Erdene Zuu monastery. They are part of the upper part of the World Heritage Site Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape. Ride horses on the steppes, meeting nomadic people, staying in a traditional tent, seeing grasslands and beautiful vistas. You will need to bring your Binoculars, telescopes and tripod. We would be pleased to have you join us! The Best Time to Travel to Mongolia: Begins in June. -

Radiation Background in the Some Towns of Uvurkhangai Province in Mongolia

International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Bioresearch Vol. 2, No. 01; 2017 www.ijaeb.org RADIATION BACKGROUND IN THE SOME TOWNS OF UVURKHANGAI PROVINCE IN MONGOLIA Ts.Erkhembayar1, N.Yasuda2, Y.Izumi2, Y.Matuo2, N.Chimedtsogzol1, Ch.Tsolmonchimeg1, B.Gandulam1 1-Department of physics, School of Applied Science, Mongolian University of Science and Technology 2-Research Institute of Nuclear Engineering, University of Fukui, Mangolia ABSTRACT This paper was focused on determination of radiation level around Kharkhorin and Khujirt towns of Uvurkhangai province. We have determined radiation background by radiation survey meters “Atomtex” and “Radi PA-1100(Horiba)”. The results were compared with the world and Japanese major cities radiation level. Keywords: radiation, dose, level, dosimeter, survey meter INTRODUCTION UVURKHANGAI AIMAG /PROVINCE/ Territory - 24,286 square miles (62,900 sq. km.) Center - Arvaikheer town, located 261 miles (420 km.) from Ulaanbaatar. Number of somons /towns/- 19 Population 118,400 Figure 1. Map of Uvurkhangai province in Mongolia www.ijaeb.org Page 68 International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Bioresearch Vol. 2, No. 01; 2017 www.ijaeb.org Uvurkhangai aimag was established in 1931. Uvurkhangai aimag is located in the central part of Mongolia. The Khangai mountain stretches in the North-West, and the Altai mountain towers in the south-west. The steppe lies in the middle of the territory. The Gobi desert is located in the South. The annual average temperature is around 34° F (1° C), and the average precipitation is about 5 inches (135 mm.). The soil in the south of the area is semi-desert grey and steppe pale areas, in the north part of the area it is mountain type brown and black. -

Töwkhön, the Retreat of Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar As a Pilgrimage Site Zsuzsa Majer Budapest

Töwkhön, The ReTReaT of öndöR GeGeen ZanabaZaR as a PilGRimaGe siTe Zsuzsa Majer Budapest he present article describes one of the revived up to the site is not always passable even by jeep, T Mongolian monasteries, having special especially in winter or after rain. Visitors can reach the significance because it was once the retreat and site on horseback or on foot even when it is not possible workshop of Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar, the main to drive up to the monastery. In 2004 Töwkhön was figure and first monastic head of Mongolian included on the list of the World’s Cultural Heritage Buddhism. Situated in an enchanted place, it is one Sites thanks to its cultural importance and the natural of the most frequented pilgrimage sites in Mongolia beauties of the Orkhon River Valley area. today. During the purges in 1937–38, there were mass Information on the monastery is to be found mainly executions of lamas, the 1000 Mongolian monasteries in books on Mongolian architecture and historical which then existed were closed and most of them sites, although there are also some scattered data totally destroyed. Religion was revived only after on the history of its foundation in publications on 1990, with the very few remaining temple buildings Öndör Gegeen’s life. In his atlas which shows 941 restored and new temples erected at the former sites monasteries and temples that existed in the past in of the ruined monasteries or at the new province and Mongolia, Rinchen marked the site on his map of the subprovince centers. Öwörkhangai monasteries as Töwkhön khiid (No. -

A History of Inner Asia

This page intentionally left blank A HISTORY OF INNER ASIA Geographically and historically Inner Asia is a confusing area which is much in need of interpretation.Svat Soucek’s book offers a short and accessible introduction to the history of the region.The narrative, which begins with the arrival of Islam, proceeds chrono- logically, charting the rise and fall of the changing dynasties, the Russian conquest of Central Asia and the fall of the Soviet Union. Dynastic tables and maps augment and elucidate the text.The con- temporary focus rests on the seven countries which make up the core of present-day Eurasia, that is Uzbekistan, Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Sinkiang, and Mongolia. Since 1991, there has been renewed interest in these countries which has prompted considerable political, cultural, economic, and religious debate.While a vast and divergent literature has evolved in consequence, no short survey of the region has been attempted. Soucek’s history of Inner Asia promises to fill this gap and to become an indispensable source of information for anyone study- ing or visiting the area. is a bibliographer at Princeton University Library. He has worked as Central Asia bibliographer at Columbia University, New York Public Library, and at the University of Michigan, and has published numerous related articles in The Journal of Turkish Studies, The Encyclopedia of Islam, and The Dictionary of the Middle Ages. A HISTORY OF INNER ASIA Princeton University Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom Published in the United States by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521651691 © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. -

STP Mongolian Brochure

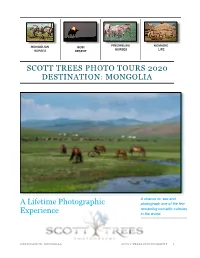

PREZWELSKI NOMADIC MONGOLIAN GOBI HORSES LIFE HORSES DESERT SCOTT TREES PHOTO TOURS 2020 DESTINATION: MONGOLIA A chance to see and A Lifetime Photographic photograph one of the few remaining nomadic cultures Experience in the world. DESTINATION: MONGOLIA SCOTT TREES PHOTOGRAPHY 1 Day 1, Jul 30. Arrival in Ulaanbaatar Arrival in Ulaanbaatar and transfer to hotel. Meeother participants and have a welcome dinner. Overnight in a 4- star hotel. Day 2, Jul 31. Ulaanbaatar ! Dalanzadgad " Three Beauties Mountains Gather at 0730 in the hotel lobby, meet our local guide then drive to the airport fort he short domestic flight down to the Gobi Desert. Land in Dalanzadgad, the capital city of the South Gobi Province. Once a remote desert town, it today serves as the center of logistics for the developing mining industry. Over the last decade, massive exploration operations have revealed the Gobi Desert has an abundance of precious metals and minerals. As a result, the once peaceful desert is being trampled by excavators, monster trucks, and massive drills, all in the hope of making a quick fortune. Luckily, most of these mines are far from the eye, but their environmental impact can be seen and felt throughout the massive desert. Upon landing in Dalanzadgad, we meet our drivers and embark on a one and a half hour drive to the “Gobis Beauties” Nature Reserve. Once at the reserve, head to “Vultures Valley”, a beautiful oasis at the foot of the “Three Beauties” mountain range. Take an easy hike along the beautiful stream, and if lucky, see some of the wildlife inhabiting the reserve. -

Mongolia Best Tour

Mongolia Best Tour Key Information: Trip Length: 10 days/9 nights. Trip Type: Easy to Moderate. Tour Code: SMT-BT-10D Specialty Categories: Adventure Expedition, Cultural Journey, Camel riding, Driving tour, E-co-Travel, Hiking, Hot spa, Local Culture, Nature & Wildlife. Meeting/Departure Points: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (excluding flights). Group size: 2-9 adults or more participants. Season: Daily, June-September. Total Distance: approx. 1400kms/875miles. Airfare Included: No. Tour Customizable: Yes Tour Highlights: Upon your arrival in Ulaanbaatar, meet Samar Magic Tours team. Mongolia Best Tour takes you to the Natural Wonders of Central Mongolia. This journey designed especially for small groups, families, private, and funny travel. The Authentic Mongol Nomadic Mongol Show (will take place from 10:00AM-12:00M). It demonstrates traditional living way of real Mongolian nomads and breeding and using of five kinds of livestock and movement from one place to another using ox, yak, camel and horse carts which are the carts. Here you will have the opportunity to hear a mongolian folk song, to see 5 herding animals, to observe the demonstration of catching and milking sheep, goat, to observe the demonstration of making dairy products. Also, we will see the Mongolian archery, playing traditional games, the demonstration of making felt and tanning, the demonstration of moving one place to another use by cart, yak freight, camel an d horse carts. Exploration to Karakorum-the Genghis (Chinggis) Khan's 13th century capital, Orkhon Waterfall (also called Ulaan Tsutgalan)-this is perfect for swimming, fishing, short trekking and walks around the surrounding area, Tsenkher Hot Spa and many more. -

Nomadic Life, Mongolia

Nomadic Life, Mongolia Takhi population inside the Khustai park which now Itinerary stands at about 450 horses. Day 1 - Ulaanbaatar During the afternoon, you have a vehicle drive in the You are met on arrival at Ulaanbaatar and transferred park in search of the Takhi. to your hotel. Dinner and overnight at the ger camp (2 – 4 guests per Please note that the itinerary may vary due to local ger). conditions, but always with your best interests in mind. After lunch (which is to your own account) visit Gandantegchinlin Monastery and the National Museum of Mongolian History. Built in 1809, the Gandantegchinlin Monastery (formerly known as the Gandan Monastery) is a Tibetan-style Buddhist monastery located in Ulan Bator. Its name is of Tibetan origin and can be translated as "Great site full of Joy". Several hundred monks currently reside there. The National Museum of Mongolian History tells the story of the country, from prehistoric times to today. Dinner downtown and overnight at the hotel. Day 3 - To Karakorum After breakfast you drive to Karakorum with a picnic lunch on the way. Karakorum (Kharkhorin) is the ancient capital of the Mongol Empire, founded in 1235 by Ogödei, the son of Genghis Khan. In 1260, Kublai Khan transfers the capital to Beijing. Karakorum was destroyed in 1388 by troops of the Ming Dynasty. Of its former glory remain mere turtle statues guarding the entrances to the city walls. Later visit Erdene Zuu monastery. In 1585, Erdene Zuu was built just outside the walls of Day 2 - Hustai National Park the ruins of the ancient capital after the introduction of Buddhism in Mongolia as the state religion. -

Mongolia Brochure

MONGOLIAMONGOLIA EXPEDITION 2020 10th -19th JULY 10th -19th JULY OVERVIEW As esoteric as a destination can be, the immensely striking Mongolia is a litmus test for a true explorer; one that promises to reveal brilliant panoramas that more than amply justify the popular adage used to describe this fascinating country – Land of the Blue Sky. Vast, secluded and thus far untouched by the mores of rampant commercialisation – Mongolia is a landlocked nation located in the midst of China and Russia. With an extremely low density of population, it offers endless vistas that are accompanied by an emptiness that possesses an enduring quality for the soul-searching adventurer. One of the last few places on the planet where the nomadic way of life is still very much prevalent, Mongolia is an absolutely distinctive experience. And we at Adventures Overland are thrilled to offer you the opportunity to live through this experience with a self-drive road trip in a 4x4 SUV. GENGHIS KHAN EQUESTRIAN STATUE Ulaanbaatar Dundgovi Dalanzadgad ROUTE MAP OVERVIEW Flaming Cliffs As esoteric as a destination can be, Khongoryn Els the immensely striking Mongolia is a Kharkhorin litmus test for a true explorer; one that Ulaanbaatar promises to reveal brilliant panoramas that more than amply justify the popular adage used to describe this fascinating country – Land of the Blue Sky. Vast, secluded and thus far untouched by the mores of rampant Ulaanbaatar commercialisation – Mongolia is a landlocked nation located in the midst Kharkhorin of China and Russia. With an extremely Dundgovi low density of population, it offers MONGOLIA endless vistas that are accompanied by an emptiness that possesses an Flaming Cliffs enduring quality for the soul-searching Khongoryn Els adventurer. -

Translation Bv Bobsin Wang Nanhai, a Chinese Territory

Translation bv Bobsin Wang Nanhai, a Chinese territory boundary as surveyed by the “Four Seas Sun- shadow-lengths Survey” of the Yuan dynasty period <ƙǮ ‘Ȝ / ϛ ɽ ’ƅ š ƅ ŗ Ă ʱ ƈ ǔ/ = By Prof. Han Zheng Hua of Xiamen University In Nanhai Zhudao Shidi Kaozheng Lunji[<ǔ/ દ ή Ȗʞ ˭ Į ŭ ã =,Collected essays of textual research on the historical geography of South Sea Islands], Zhonghua Bookstore Publisher, 1981. In ‘Nanhai Zhudao Shidi Lunzheng’[@ǔ/ દ ή Ȗʞ ŭ Į A,Textual research essays on the historical geography of Southsea islands], Hong Kong Chinese University’s Asia Study Center, 2003. Translated by Wang Guan Yio Ever since 1276 the year the Mongols captured Hanzhou, the capital of South Song Dynasty, the die of unifying entire China by the Mongolian Yuan dynasty was thrown. The Mongolian imperial court was then determined to reform the existing Song calendar by setting up the Astronomical Bureau, which later became the Astronomical Academy. In making a calendar, on-the-spot survey is of primary importance. It must carry out observations and sundial readings at various places from the North to the South of the whole country to collect data so that the calendar system reform can have real help and solid ground. In the spring of 1279, Zhao Bing ( ʏ ), the emperor of Southern Song Dynasty, was “defeated and fled to Yai Shan (Ƃ Ŷ )”(1). After receiving the news, Kublai Khan, the First Emperor of the Yuan Dynasty, sent Guo Shoujing (˦ ʲ ) to Nanhai(ǔ/ ) to survey the sundial’s noon shadow lengths”(2). -

Quaternary Sediment Architecture in the Orkhon Valley (Central Mongolia) Inferred from Capacitive Coupled Resistivity and Georadar Measurements MARK

Geomorphology 292 (2017) 72–84 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Quaternary sediment architecture in the Orkhon Valley (central Mongolia) inferred from capacitive coupled resistivity and Georadar measurements MARK ⁎ Sonja Mackensa, Norbert Klitzschb, Christoph Grütznerc, , Riccardo Klingerd a Geotomographie GmbH, Am Tonnenberg 18, Neuwied 56567, Germany b Applied Geophysics and Geothermal Energy, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen 52074, Germany c COMET, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Madingley Rise, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0EZ, UK d Geolicious, Binzstr. 48, Berlin 13189, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Detailed information on shallow sediment distribution in basins is required to achieve solutions for problems in Ground penetrating radar Quaternary geology, geomorphology, neotectonics, (geo)archaeology, and climatology. Usually, detailed Capacitive coupled resistivity information is obtained by studying outcrops and shallow drillings. Unfortunately, such data are often sparsely Landscape evolution distributed and thus cannot characterise entire basins in detail. Therefore, they are frequently combined with Permafrost remote sensing methods to overcome this limitation. Remote sensing can cover entire basins but provides Mongolia information of the land surface only. Geophysical methods can close the gap between detailed sequences of the Orkhon Valley shallow sediment inventory from drillings at a few spots and continuous surface information from remote sensing. However, their interpretation in terms of sediment types is often challenging, especially if permafrost conditions complicate their interpretation. Here we present an approach for the joint interpretation of the geophysical methods ground penetrating radar (GPR) and capacitive coupled resistivity (CCR), drill core, and remote sensing data. The methods GPR and CCR were chosen because they allow relatively fast surveying and provide complementary information.