Rspb Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orkney Native Wildlife Project

The Orkney Native Wildlife Project Strategic Environmental Assessment Environmental Report June 2020 1 / 31 Orkney Native Wildlife Project Environmental Report 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Project Summary and Objectives ............................................................................. 4 1.2 Policy Context............................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Related Plans, Programmes and Strategies ............................................................ 4 2. SEA METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Topics within the scope of assessment .............................................................. 6 2.2 Assessment Approach .............................................................................................. 6 2.3 SEA Objectives .......................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Limitations to the Assessment ................................................................................. 8 3. ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PROJECT AREA ............................. 8 3.1 Biodiversity, Flora and Fauna ................................................................................... 8 3.2 Population and Human Health .................................................................................. 9 -

Genetic Structure in Orkney Island Mice

Genetic structure in Orkney island mice: isolation promotes morphological diversification P Chevret, Lionel Hautier, Guila Ganem, Jeremy Herman, Sylvie Agret, Jean-Christophe Auffray, Sabrina Renaud To cite this version: P Chevret, Lionel Hautier, Guila Ganem, Jeremy Herman, Sylvie Agret, et al.. Genetic structure in Orkney island mice: isolation promotes morphological diversification. Heredity, Nature Publishing Group, 2021, 126 (2), pp.266-278. 10.1038/s41437-020-00368-8. hal-02950610 HAL Id: hal-02950610 https://hal-cnrs.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02950610 Submitted on 23 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Genetic structure in Orkney island mice: isolation promotes morphological diversification 2 3 Pascale Chevret 1, Lionel Hautier 2, Guila Ganem 2, Jeremy Herman 3, Sylvie Agret 2, Jean-Christophe 4 Auffray 2, Sabrina Renaud 1 5 6 1 Laboratoire de Biométrie et Biologie Evolutive, UMR 5558 CNRS Université Lyon 1, Université de 7 Lyon, Campus de la Doua, 69100 Villeurbanne, France 8 2 Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution de -

The Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney | 41

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 145 (2015), 41–89 THE KNOWE OF ROWIEGAR, ROUSAY, ORKNEY | 41 The Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney: description and dating of the human remains and context relative to neighbouring cairns Margaret Hutchison,* Neil Curtis* and Ray Kidd* ABSTRACT The Neolithic chambered cairn at Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney, was excavated in 1937 as part of a campaign that also saw excavations at sites such as Midhowe and the Knowe of Lairo. Not fully published at the time, and with only partial studies since, the human bone assemblage has now been largely re-united and investigated. This included an osteological study and AMS dating of selected bones from this site and other Rousay cairns in the care of University of Aberdeen Museums, as well as the use of archival sources to attempt a reconstruction of the site. It is suggested that the human remains were finally deposited as disarticulated bones and that the site was severely damaged at the time the adjacent Iron Age souterrain was constructed. The estimation of the minimum number of individuals represented in the assemblage showed a significant preponderance of crania and mandibles, suggesting the presence of at least 28 heads, along with much smaller numbers of other bones, while age and sex determinations showed a preponderance of adult males. Seven skulls showed evidence of violent trauma, while evidence from both bones and teeth indicates that there were high levels of childhood dietary deficiency. Although detailed analysis of the dates was hampered by the ‘Neolithic plateau’, a Bayesian analysis of the radiocarbon determinations suggests the use of the site during the period 3400 to 2900 cal BC. -

Identification and Modelling of a Representative Vulnerable Fish Species for Pesticide Risk Assessment in Europe

Identification and Modelling of a Representative Vulnerable Fish Species for Pesticide Risk Assessment in Europe Von der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften der RWTH Aachen University zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Lara Ibrahim, M.Sc. aus Mazeraat Assaf, Libanon Berichter: Universitätsprofessor Dr. Andreas Schäffer Prof. Dr. Christoph Schäfers Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 30. Juli 2015 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Universitätsbibliothek online verfügbar Erklärung Ich versichere, dass ich diese Doktorarbeit selbständig und nur unter Verwendung der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Weiterhin versichere ich, die aus benutzten Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht zu haben. Lara Ibrahim Aachen, am 18 März 2015 Zusammenfassung Die Zulassung von Pflanzenschutzmitteln in der Europäischen Gemeinschaft verlangt unter anderem eine Abschätzung des Risikos für Organismen in der Umwelt, die nicht Ziel der Anwendung sind. Unvertretbare Auswirkungen auf den Naturhalt sollen vermieden werden. Die ökologische Risikoanalyse stellt die dafür benötigten Informationen durch eine Abschätzung der Exposition der Organismen und der sich daraus ergebenden Effekte bereit. Die Effektabschätzung beruht dabei hauptsächlich auf standardisierten ökotoxikologischen Tests im Labor mit wenigen, oft nicht einheimischen Stellvertreterarten. In diesen Tests werden z. B. Effekte auf das Überleben, das Wachstum und/oder die Reproduktion von Fischen bei verschiedenen Konzentrationen der Testsubstanz gemessen und Endpunkte wie die LC50 (Lethal Concentrations for 50%) oder eine NOEC (No Observed Effect Concentration, z. B. für Wachstum oder Reproduktionsparameter) abgeleitet. Für Fische und Wirbeltiere im Allgemeinen beziehen sich die spezifischen Schutzziele auf das Überleben von Individuen und die Abundanz und Biomasse von Populationen. -

The Breeding Bird Survey 1994-1995

TheBreeding Bird Survey1994-1995 The BreedingBird SurveyReport 1994-1995 The Breeding Bird Suntey 1994-7995 ReportlVumber 1 by R.D.Gregory & R.I.Bashford Withthe assistance of D.E.Balmeq, I.H. Marchant, A.M. Wilson & S.R.Baillie Publishedby BritishTrust for Ornithology,Joint Nature Conservation Committee and RoyalSociety for theProtection of Birds, August1996 @ BritishTrust for Ornithology,Joint Nature Conservation Committee and RoyalSociety for theProtection of Birds,1996 *Rttfi& CONSERVATION BritishTrust for 0rnithology COMMITTEE F E H rsBN0 e037e363 6 (BTO) * r€s g ffi 116 Hii: The Breed Bird SurveyReporc 1994-1995 BREEDINGBIRDSURYEY Organisedand tunded by: British Trust for Orntthology TheNational Centre for Ornithology,The Nunnery Thetford,Norfolk IP24 2PU Joint Natue ConsewationCommittee MonktoneHouse, City Road, PeterboroughPEI UY RoyalSociety for the Pmtectionof Birds TheLodge, Saldy, BedfordshireSGl9 zDL BBSNauonal Organiser: Richard Bashford - Briush Trust for Ornithology Thisreport is providedfree to all BBScounters, none of whom receivefinancial rewards for their invaluablework. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Tiis is the first BreedingBird suruey[BBs) Annual Report covering the yearslgg4 and 1995. The datacontained within havebeen collected almostentirely by the effo s of nearly2000 volunteerornithologisis without whom, the BBSwould not be possible.This repoft, and thoseto follow, are testamentto the generousefforts of highly skiled volunteers. We would alsolike to thank member; of RSPBstaff ilscotland for their assistancein carrying out professionalfieldwork in remote areas. ^ The BBSis organisedby the Bdtish Trust for Ornithologyand jointly funded by the British Trust for Ornithology,the Joint Nature ConseNation Committee(on behalf of EnglishNature, Scottish Naturt Heritage,Countryside Council for walesand the Deiartmentof the Environmentfor Northemlreland)and the Royalsociety for the Protectionof Biids. -

The Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney | 41

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 145 (2015), 41–89 THE KNOWE OF ROWIEGAR, ROUSAY, ORKNEY | 41 The Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney: description and dating of the human remains and context relative to neighbouring cairns Margaret Hutchison,* Neil Curtis* and Ray Kidd* ABSTRACT The Neolithic chambered cairn at Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney, was excavated in 1937 as part of a campaign that also saw excavations at sites such as Midhowe and the Knowe of Lairo. Not fully published at the time, and with only partial studies since, the human bone assemblage has now been largely re-united and investigated. This included an osteological study and AMS dating of selected bones from this site and other Rousay cairns in the care of University of Aberdeen Museums, as well as the use of archival sources to attempt a reconstruction of the site. It is suggested that the human remains were finally deposited as disarticulated bones and that the site was severely damaged at the time the adjacent Iron Age souterrain was constructed. The estimation of the minimum number of individuals represented in the assemblage showed a significant preponderance of crania and mandibles, suggesting the presence of at least 28 heads, along with much smaller numbers of other bones, while age and sex determinations showed a preponderance of adult males. Seven skulls showed evidence of violent trauma, while evidence from both bones and teeth indicates that there were high levels of childhood dietary deficiency. Although detailed analysis of the dates was hampered by the ‘Neolithic plateau’, a Bayesian analysis of the radiocarbon determinations suggests the use of the site during the period 3400 to 2900 cal BC. -

The Historic England Zooarchaeology Reference Collection: Description and List

THE HISTORIC ENGLAND ZOOARCHAEOLOGY REFERENCE COLLECTION: DESCRIPTION AND LIST Polydora Baker, Eva Fairnell, Fay Worley SUMMARY This document lists the current holdings of the Historic England zooarchaeology reference collection held at Fort Cumberland, Portsmouth, UK. A total of 3308 specimens is listed, of which 2387 are complete skeletons. These include approximately 115 species of mammal, 220 species of bird, 9 species of reptile, 5 species of amphibian and 55 species of fish. The vertebrate skeleton reference collection is available for consultation: please refer to our access policy (http://www.historicengland.org.uk/research/approaches/research methods/Archaeology/zooarchaeology/). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The original collection list and description were compiled by Elaine Corke, Simon Davis and Sebastian Payne, and subsequently curated by Polydora Baker, Fay Worley, Mick Revill and Eva Fairnell. Complete specimen data recorded on individual paper records were added to the database by Gemma Ayton. We are grateful to Manny Lopez and Hugh Corley for IT support. COLLECTION LOCATION Historic England, Fort Cumberland, Fort Cumberland Rd, Portsmouth PO4 9LD, UK CONTACT DETAILS Zooarchaeology, Environmental Studies, Historic England, Fort Cumberland, Fort Cumberland Rd, Portsmouth PO4 9LD, UK Polydora Baker, Tel. 02392 856774. E-mail: [email protected] Fay Worley, Tel.: 02392 856789. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Historic England Zooarchaeology Reference Collection web list July 2020 INTRODUCTION The role of the Historic England Research Department vertebrate skeleton reference collection is to: • enable the identification and interpretation of animal remains from archaeological sites in England • provide comparative material for a long-term study of the development of the ‘traditional’ British domesticated animals • facilitate research on the biogeography of extinct and introduced species. -

Scotland's Highlands, Isle of Skye and Orkney Islands

Pennsbury Land Trust trip to SCOTLAND’S HIGHLANDS, ISLE OF SKYE AND ORKNEY ISLANDS May 23 - June 6, 2008 Registration deadline: February 15, 2008 Follow the routes of seabirds and stone-age man, red stags and Vikings through the extraordinarily beautiful northernmost points in Britain, in the height of the spring. Northern Scotland and its surrounding islands are rich in natural history, archeology, and Celtic and Norse Culture. Join us for an in-depth look at how the interplay of ancient land forms, natural and human history, and many human cultures combine to form the Scottish landscape you see today. Our small group will explore remote glacially sculptured glens, mountain lochs and burns, delicate moorlands, private Highland gardens, castles, cairns, Neolithic villages, golden eagle aeries, otter runs and puffin colonies. The Orkney Islands are world famous for their sea birds, archaeology, and history and contain the greatest concentration of archeological monuments in Europe. Walks are at a leisurely pace; days on your own to pursue personal interests are an option. Leadership is provided by Karen Travers, international trip leader, biologist, and Land Trust president (her 8th trip to Scotland) and Scottish naturalists. At Aigas Field Centre near Beauly, enjoy Highland hospitality at the home of Sir John and Lady Lister-Kaye. This Victorian-Gothic castle and its surrounding lodges combine modern comfort with traditional atmosphere. The excellent meals featuring Highland specialties are served baronial style in the Great Hall. Well-equipped hotels in West Highlands and Orkney are conveniently close to interesting island sites. Accommodations are double-occupancy with private baths. -

The Annals of Scottish Natural History

RETURN TO LIBRARY OF MARINE BIOLOGICAL LABORATORY WOODS HOLE, MASS. LOANED BY AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY The Annals OF Scottish Natural History A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE WITH WHICH IS INCORPORATED Naturalist EDITED BY ]. A. HARVIE-BROWN, F.R.S.E., F.Z.S. MEMBER OF THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION JAMES W. H. TRAIL, M.A., M.D., F.R.S., F.L.S. PROFESSOR OF BOTANY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN AND WILLIAM EAGLE CLARKE, F.L.S., F.R.S.E. NATURAL HISTORY DEPARTMENT, ROYAL SCOTTISH MUSEUM, EDINBURGH 1905 EDINBURGH DAVID DOUGLAS, CASTLE STREET LONDON: R. H. PORTER, 7 PRINCES ST., CAVENDISH SQUARE The Annals of Scottish Natural History NO. 53] 1905 [JANUARY ON THE VOLE AND SHREW OF THE ORKNEY ISLANDS. By WM. EAGLE CLARKE. With Report by Prof. O. CHARNOCK BRADLEY, M.B., C.M. IT is a somewhat remarkable fact that since 1848, when Messrs. Baikie and Heddle published their excellent for " the date Historia Naturalis Orcadensis," until the past year, 1904, no naturalist seems to have paid any attention to either the Vole or the Shrew inhabiting the Orkney Islands. The consequence is that the misleading pardon- ably misleading, it should be said statements of these authors regarding the specific identity of these Orcadian mammals have been unfortunately accepted by and repeated in all the subsequent writings on the subject with which I am acquainted. " " As regards the Vole, in the Zoologist for July 1 904 (pp. 241-246), Mr. J. G. Millais astonished British naturalists by describing the Orcadian Vole as a species new to science under the name of Microtus orcadensis, and as peculiar to 1 the Archipelago. -

Common Standards Monitoring for Designated Sites: First Six Year Report 3 Common Standards Monitoring for Designated Sites: First Six Year Report

Common Standards Monitoring for Designated Sites: First Six Year Report 3 Common Standards Monitoring for Designated Sites: First Six Year Report Legislation in the United Kingdom makes provision for The report is presented in four parts: Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) designated for their biological or geological features. By March 2005, 1. Summary there were 6,569 SSSIs in England, Scotland and Wales, 2. Geology and a further 225 Areas of Special Scientific Interest in 3. Species Northern Ireland (ASSIs), covering between them over 4. Habitats 2.4 million hectares. The first part is an introduction and executive summary The United Kingdom has also entered into international which draws together results across the site networks as commitments to establish a network of protected sites a whole. The subsequent three parts present the detailed under the Ramsar Convention. Special Protection Areas data collated in 44 reporting categories. A standardised set (SPAs) and Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) are of presentations and graphics have been created for each required to be established under the EC Birds and Habitats reporting category which portray the detailed results. Directives respectively. In many cases, the same area of land is protected by more than one designation; the basic This information can also be found on the JNCC website building block is the SSSI or ASSI, which underpins the at www.jncc.gov.uk/page-3520; these data will vast majority of the international site designations. be updated at regular intervals. The basis of the common standards for site monitoring is that those special features for which the site was designated are assessed to determine whether they are in a satisfactory condition. -

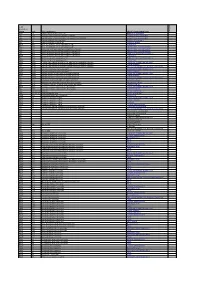

Lead Ecosystem Group Code SBL Habitat Name UKBAP Priority

Lead Ecosystem Group code SBL Habitat name UKBAP Priority habitat name Category M&C H7 Calluna vulgaris-Scilla verna heath Maritime cliff and slopes 3 F&L CG2 Festuca ovina-Helictotrichon pratense grassland Lowland calcareous grassland 1 F&L CG7 Festuca ovina-Hieracium pilosella-Thymus polytrichus grassland Lowland calcareous grassland 1 M&C H7 Calluna vulgaris-Scilla verna heath Maritime cliff and slopes 3 F&L H8 Calluna vulgaris-Ulex gallii heath Lowland heathland 2 F&W M13 Schoenus nigricans-Juncus subnodulosus mire Lowland fens 1 F&L M13 Schoenus nigricans-Juncus subnodulosus mire Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M21 Narthecium ossifragum-Sphagnum papillosum valley mire Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Purple moor grass and rush pastures 2 F&W M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Lowland fens 1 F&L M26 Molinia caerulea-Crepis paludosa fen Purple moor grass and rush pastures 2 F&W M26 Molinia caerulea-Crepis paludosa fen Lowland fens 1 F&W MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Coastal and floodplain grazing marsh 3 M&C MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Coastal saltmarsh 3 F&L MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Open mosaic habitats on previously developed land 3 F&W MG12 Festuca arundinacea coarse grassland Coastal -

Scottish Birds 34:3 (2015)

Contents Scottish Birds 34:3 (2015) 194 President’s Foreword C. McInerny PAPERS 195 Amendments to The Scottish List: species and subspecies The Scottish Birds Record Committee 199 Nest sites of House Sparrows and Tree Sparrows in South-east Scotland H.E.M. Dott 202 Peregrines in North-east Scotland in 2014 - further decline in the uplands North East Scotland Raptor Study Group 207 Changes in breeding wader populations of the Uist machair between 1983 and 2014 J. Calladine, E.M. Humphreys & J. Boyle SHORT NOTES 216 Crossbills feeding on grit from wind farm access tracks T. Marshall 217 Predation of well-grown Capercaillie chick probably by a Pine Marten K. Fletcher, P. Warren & D. Baines 219 An analysis of Barn Owl pellets from Nithsdale, Dumfries & Galloway W. & H. McMichael 221 Successful breeding by close-nesting White-tailed Eagles and Ospreys in Scotland J.D. Taylor, R.A. Broad, D.C. Jardine 223 Letter to the Editors: Fault bars S. Menzie OBITUARIES 227 Archie Mathieson (1937–2014) P. Gordon 228 Elizabeth Munro Smith (1922–2015) D. McLean 229 John Philip Busby (1928–2015) D. Woodhead 231 J. Bryan Nelson (1932–2015) S. Wanless ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 236 Waterston House is ten years old 241 NEWS AND NOTICES 245 A roosting male Merlin in Lothian, winter 2014/15 D. Allan 247 Satellite tagging Kestrels G. Riddle 248 Sea storms and skerries: where do Shags go in winter? H. Grist, J. Reid, F. Daunt, S. Wanless 252 The 2015 Scottish Birdfair 23–24 May 2015 J. Cleaver 255 Bird photography for the aged - a weight off my shoulders J.