Intersections of Theatre Theories of Spectatorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Edition VOLUME 6 ISSUE 3

Mise en Scéne Winter Edition VOLUME 6 ISSUE 3 CSUEB Spellers take the stage in Inside this Issue "The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee" Director, Marc Jacobs, shares his thoughts on this musical comedy Upcoming Shows 2 My first encounter with "The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee" was with the Post Street Theatre in San Francisco, 10 years ago. This was the first Our Students 3 production after the original Broadway cast, and I had several friends in the show, which was cast locally. One of the cast members was James Monroe Checking In 4 Iglehart (CSUEB Graduate) who had been in previous musicals I had directed in San Jose. James has since gone on to win the Tony Award as the Genie in Disney’s Broadway production of "Aladdin." James was playing 'Comfort Guest Artists 5 Counselor' Mitch Mahoney in "Spelling Bee," and his performance was so perfect that the producers decided to model every subsequent 'Mitch' on James’ performance. Another friend in the show was Aaron Albano, who had Featured Faculty 7 started out as one of the teenagers in my production of The Music Man that I directed in San Jose, and has since gone on to appear on Broadway in The Wiz, Newsies, and currently in Allegiance. The San Francisco company of Information 9 "Spelling Bee" was so successful, that the producers ultimately used those actors to replace the Broadway company once the original actors were ready to leave the show. One of those original actors, Sarah Salzburg ‒ the original “Schwarzy” in ‘Spelling Bee - was the daughter of a good friend of mine. -

MELODY BETTS Resume

MELODY A. BETTS AEA, SAG-AFTRA Height: 5’3” Hair: Brown Eyes: Light Brown PROFESSIONAL/REGIONAL THEATRE Secret of My Success Rose Lockhart Paramount Theater Gordon Greenberg/ Steve Rosen Waitress Becky. Nurse Norma Brooks Atkinson Theater/ National Tour Diane Paulus The Sound of Music Mother Abbess National Tour Jack O'Brien Invisible Thread Rain Lady, Joy u/s Second Stage Theater Diane Paulus Nunsense Sister Hubert Marriott Theatre Rachel Rockwell All Shook Up Sylvia Marriott Theatre Marc Robin The Boys from Syracuse Luce Drury Lane Oakbrook David H. Bell Godspell Sonia-“Oh Bless the Lord” LTOTS Ann Niemann Seussical Sour Kangaroo/Bird Girl Drury Lane Oakbrook Rachel Rockwell Do Patent Leather Shoes… Sister Helen LTOTS Ann Niemann Cinderella Fairy Godmother Marriott Theatre Rachel Rockwell Thoroughly Modern Millie Muzzy Van Hossmere Drury Lane Oakbrook Bill Osetek Comedy of Errors Courtesan/Abbess Chicago Shakespeare David H. Bell Ragtime*** Sarah’s Friend Drury Lane Oakbrook Rachel Rockwell The Drowsy Chaperone Trix the Aviatrix Marriott Theatre Marc Robin Once on This Island Asaka Marriott Theatre David H. Bell The Nativity Mother of Mary Goodman Theatre A.T.Douglas Intimate Apparel Esther Mills Simpkins Theatre Egla Hasaan Blithe Spirit Madame Arcati Horrabin Theatre Tamara Izlar The Monument Mejra Simpkins Theatre Jeff Day Mud, River, Stone Ama Simpkins Theatre Tamara Izlar Othello Emilia Hainline Theatre Egla Hasaan Pinocchio Blue Fairy/Story Teller Chicago Shakespeare Rachel Rockwell Motherhood the Musical Tasha Royal George Theater -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

CAMILLE A. BROWN Choreographer, Performer, Teacher, Cultural Innovator

CAMILLE A. BROWN Choreographer, Performer, Teacher, Cultural Innovator FOUNDER/ARTISTIC DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER/PERFORMER 2006-present Camille A. Brown & Dancers, contemporary dance company based in New York City www.camilleabrown.org FILM/TELEVISION Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom George C. Wolfe Netflix Jesus Christ Superstar Live David Leveaux NBC BROADWAY Disney’s Aida (Fall 2020) Schele Williams Broadway Theatre TBD Soul Train (2021-22) Kamilah Forbes Broadway Theatre TBD Basquiat (TBD) John Doyle Broadway Theatre TBD Pal Joey (TBD) Tony Goldwyn Broadway Theatre TBD Choir Boy Trip Cullman Samuel Friedman Theatre (MTC) *nominee Tony, Drama Desk Awards Once on This Island Michael Arden Circle in the Square Theatre *nominee Chita Rivera, Outer Critics Circle, Drama Desk Awards A Streetcar Named Desire Emily Mann Broadhurst Theatre OFF-BROADWAY/NEW YORK The Suffragists (October 2020) Leigh Silverman The Public Theater Thoroughly Modern Millie Lear DeBessonet Encores! City Center For Colored Girls Leah Gardiner The Public Theater Porgy and Bess James Robinson The Metropolitan Opera Much Ado About Nothing Kenny Leon Shakespeare in the Park *winner: Audelco Award 2019 Toni Stone Pam McKinnon Roundabout Theatre Company This Ain’t Not Disco Darko Trensjak Atlantic Theatre Company Bella: An American Tall Tale Robert O’Hara Playwrights HoriZons *winner: Lucille Lortel Award 2017 Cabin in the Sky Ruben Santiago-Hudson New York City Center (Encores!) Fortress of Solitude Daniel Aukin The Public Theater *nominee Lucille Lortel Award tick, tick…BOOM! Oliver Butler New York City Center (Encores!) The Box: A Black Comedy Seth Bockley The Irondale Soul Doctor Danny Wise New York Theatre Workshop 450 West 24th Street Suite 1C New York New York 10011 (212) 221-0400 Main (212) 881-9492 Fax www.michaelmooreagency.com Department of Consumer Affairs License #2001545-DCA REGIONAL Treemonisha (May 2022) Camille A. -

The-Music-Of-Andrew-Lloyd-Webber Programme.Pdf

Photograph: Yash Rao We’re thrilled to welcome you safely back to Curve for production, in particular Team Curve and Associate this very special Made at Curve concert production of Director Lee Proud, who has been instrumental in The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber. bringing this show to life. Over the course of his astonishing career, Andrew It’s a joy to welcome Curve Youth and Community has brought to life countless incredible characters Company (CYCC) members back to our stage. Young and stories with his thrilling music, bringing the joy of people are the beating heart of Curve and after such MUSIC BY theatre to millions of people across the world. In the a long time away from the building, it’s wonderful to ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER last 15 months, Andrew has been at the forefront of have them back and part of this production. Guiding conversations surrounding the importance of theatre, our young ensemble with movement direction is our fighting for the survival of our industry and we are Curve Associate Mel Knott and we’re also thrilled CYCC LYRICS BY indebted to him for his tireless advocacy and also for alumna Alyshia Dhakk joins us to perform Pie Jesu, in TIM RICE, DON BLACK, CHARLES HART, CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON, this gift of a show, celebrating musical theatre, artists memory of all those we have lost to the pandemic. GLENN SLATER, DAVID ZIPPEL, RICHARD STILGOE AND JIM STEINMAN and our brilliant, resilient city. Known for its longstanding Through reopening our theatre we are not only able to appreciation of musicals, Leicester plays a key role make live work once more and employ 100s of freelance in this production through Andrew’s pre-recorded DIRECTED BY theatre workers, but we are also able to play an active scenes, filmed on-location in and around Curve by our role in helping our city begin to recover from the impact NIKOLAI FOSTER colleagues at Crosscut Media. -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

July 14–19, 2019 on the Campus of Belmont University at Austin Peay State University

July 14–19, 2019 On the Campus of Belmont University at Austin Peay State University OVER 30 years as Tennessee’s only Center of Excellence for the Creative Arts OVER 100 events per year OVER 85 acclaimed guest artists per year Masterclasses Publications Performances Exhibits Lectures Readings Community Classes Professional Learning for Educators School Field Trip Grants Student Scholarships Learn more about us at: Austin Peay State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, disability, age, status as a protected veteran, genetic information, or any other legally protected class with respect to all employment, programs and activities sponsored by APSU. The Premier Summer Teacher Training Institute for K–12 Arts Education The Tennessee Arts Academy is a project of the Tennessee Department of Education and is funded under a grant contract with the State of Tennessee. Major corporate, organizational, and individual funding support for the Tennessee Arts Academy is generously provided by: Significant sponsorship, scholarship, and event support is generously provided by the Belmont University Department of Art; Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee; Dorothy Gillespie Foundation; Solie Fott; Bobby Jean Frost; KHS America; Sara Savell; Lee Stites; Tennessee Book Company; The Big Payback; Theatrical Rights Worldwide; and Adolph Thornton Jr., aka Young Dolph. Welcome From the Governor of Tennessee Dear Educators, On behalf of the great State of Tennessee, it is my honor to welcome you to the 2019 Tennessee Arts Academy. We are so fortunate as a state to have a nationally recognized program for professional development in arts education. -

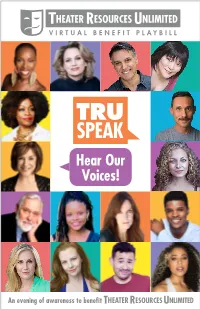

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

Southern Comfort

FROM THE NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MUSICAL THEAtre’s PresideNT Welcome to our 24th Annual Festival of New Musicals! The Festival is one of the highlights of the NAMT year, bringing together 600+ industry professionals for two days of intense focus on new musical theatre works and the remarkably talented writing teams who create them. This year we are particularly excited not only about the quality, but also about the diversity—in theme, style, period, place and people—represented across the eight shows that were selected from over 150 submissions. We’re visiting 17th-century England and early 20th century New York. We’re spending some time in the world of fairy tales—but not in ways you ever have before. We’re visiting Indiana and Georgia and the world of reality TV. Regardless of setting or stage of development, every one of these shows brings something new—something thought-provoking, funny, poignant or uplifting—to the musical theatre field. This Festival is about helping these shows and writers find their futures. Beyond the Festival, NAMT is active year-round in supporting members in their efforts to develop new works. This year’s Songwriters Showcase features excerpts from just a few of the many shows under development (many with collaboration across multiple members!) to salute the amazing, extraordinarily dedicated, innovative work our members do. A final and heartfelt thank you: our sponsors and donors make this Festival, and all of NAMT’s work, possible. We tremendously appreciate your support! Many thanks, too, to the Festival Committee, NAMT staff and all of you, our audience. -

Religious Roots Tangle with the Groovy ’60S - the New York Times

'Kinky Boots' Sets April 4 Broadway Opening - NYTimes.com AUGUST 15, 2012, 3:13 PM ‘Kinky Boots’ Sets April 4 Broadway Opening By PATRICK HEALY "Kinky Boots," one of the most anticipated musicals of the new Broadway season, with Cyndi Laupermaking her debut as a songwriter for the stage, will begin performances on March 5, 2013, at the Al Hirschfeld Theater and open on April 4, the producers announced on Wednesday. Based on a 2005 British filmabout a shoe factory heir who enlists a drag queen to help save the family business, "Kinky Boots" will star the Tony Award nominee Stark Sands ("Journey's End," "American Idiot") as the scion Charlie and Billy Porter (Belize in the Off Broadway revival of "Angels in America") as the resourceful Lola. The show's book writer is Harvey Fierstein, who won a Tony for his book for "La Cage aux Folles" and was nominated in the category last season for the Broadway musical "Newsies." Ms. Lauper, a Grammy-winning pop icon of the 1980s, has written the music and lyrics for the production, which will have an out-of-town run in Chicago this fall. Jerry Mitchell will direct, and the lead producers are Daryl Roth and Hal Luftig. Like "Kinky Boots," most of the new Broadway musicals expected this season are inspired by movies or books; the others include "Bring It On," "Rebecca," "A Christmas Story," "Matilda," "Diner," and "Hands on a Hardbody." http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/15/kinky-boots-sets-april-4-broadway-opening/?pagewanted=print[8/16/2012 9:52:02 AM] Religious Roots Tangle With the Groovy ’60s - The New York Times August 15, 2012 THEATER REVIEW Religious Roots Tangle With the Groovy ’60s By JASON ZINOMAN Wearing a bushy beard and the absent-minded expression of a father preoccupied with work at the dinner table, Eric Anderson, who plays the Jewish singer Shlomo Carlebach in the bio-musical “Soul Doctor,” appears smaller than life. -

Let It Go Lyrics

Let It Go ‘Let it Go’ Lyrics Idina Menzel’s ‘Let It Go’ Lyrics The snow glows white on the mountain tonight Not a footprint to be seen A kingdom of isolation And it looks like I’m the queen The wind is howling like this swirling storm inside Couldn’t keep it in, Heaven knows I tried Don’t let them in, don’t let them see Be the good girl you always have to be Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know Well, now they know Let it go, let it go Can’t hold it back anymore Let it go, let it go Turn away and slam the door I don’t care what they’re going to say Let the storm rage on The cold never bothered me anyway It’s funny how some distance makes everything seem small And the fears that once controlled me can’t get to me at all It’s time to see what I can do To test the limits and break through No right, no wrong, no rules for me I’m free Let it go, let it go I’m one with the wind and sky Let it go, let it go You’ll never see me cry Here I stand and here I’ll stay Let the storm rage on My power flurries through the air into the ground My soul is spiraling in frozen fractals all around And one thought crystallizes like an icy blast I’m never going back, the past is in the past Let it go, let it go And I’ll rise like the break of dawn Let it go, let it go That perfect girl is gone Here I stand in the light of day Let the storm rage on The cold never bothered me anyway Demi Lovato’s ‘Let It Go’ Lyrics Let it go, let it go Can’t hold it back anymore Let it go, let it go Turn my back and slam the door The snow glows white on the mountain tonight -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve.