Citkovitz Claudia Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Sewer System LITTLE SILVER—Voters Here Said' in Resounding Fashion Yesterday They Do Not Want a Sewerage Sys- Tem Installed

' ••'":.¥&!* '\ •:•; Distribution Vt*r taiuf mi tMfefct. Part. tf ***** tmmtm. Hfefc to* Today dap, 71. Low (aright, la Mf. See pace 2. 13,950 An Independent Newspaper Under Same Ownership Since 1878 VOLUME 82, NO. 199 limed Dally, Monday through Frtdiy, entered a< Second Class Matter ^PERRWEEK at tho Post Office at Red Bank. N. J., under the Act of March 3. 187!), RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, MAY 19, 1960 7c PER COPY 3 PAGE ONE Voters Say 'No' To Sewer System LITTLE SILVER—Voters here said' in resounding fashion yesterday they do not want a sewerage sys- tem installed. Soviet Asks New Klirush The Mayor and Council, using the vote as a guide, are expected to go along with the results and take no U.N. Action Blast Buries action to start such a project. On Spying Salvage Hope Seek Joint It was by better than a UNITED NATIONS, N. PARIS (AP)—A nervous 2-1 margin that the sys- Y. (AP) — The Russians world faced a dangerously Meeting On tem was turned down. pressed today for a speedy uncertain future today as There were 953 persons against U.N. Security Council hostile chiefs of the United Rezoning he proposal and -439 for it. meeting on American spy Residents who would have been flights over Russia to get States and the Soviet Un- NEW SHREWSBURY — The affected by the system, did the ion turned away from the Planning Board last night direc- the jump on a U.S. pro- voting. The balloting was done posal for international aerial in- East-West battle at the ted its secretary, Prancis by mail. -

WRA SUMMER READING PROGRAM 2018 Western Reserve Academy Leisure Summer Reading 2018

WRA SUMMER READING PROGRAM 2018 Western Reserve Academy Leisure Summer Reading 2018 Most members of the Reserve community find pleasure in reading. For those of us tied to the academic calendar, summers and holidays give us what we need most—time. With that in mind, we offer students this list of recommended books for summer reading. This list is intended for student LEISURE reading. We hope the variety piques student interest and provides the opportunity to expand horizons, satisfy curiosity, and/or offer an enjoyable escape. Titles include: “classics” to recently published titles, relatively easy to challenging reading levels, and a variety of genres covering diverse subjects. Also included is a list of recommended websites to locate further suggestions for award-winning books and titles of interest. This list is updated annually by members of the John D. Ong library staff. Titles are recommended by members of the WRA community or by respected review sources including the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA), a division of the American Library Association. A few titles have frank passages that mirror some aspects of life explicitly. Therefore, we urge parents to explore the titles your teenagers choose and discuss the book as well as the choice with them. All the books on this list should be available in libraries and/or bookstores. The Ong Library will also arrange for a special “summer checkout” for anyone interested. Just ask at the library front desk. Enjoy your summer and your free time, and try to spend some of it reading! Your feedback about any title on this list is welcome—and we also welcome your recommendations for titles to add in the future. -

Rusk Rehabilitation

2016 / YEAR IN REVIEW Rusk Rehabilitation TOP 10 37% ADVANCING IN U.S. NEWS & INCREASE IN VALUE BASED WORLD REPORT OUTPATIENT VISITS MEDICINE NYU LANGONE MEDICAL CENTER 550 First Avenue, New York, NY 10016 NYULANGONE.ORG Contents 1 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 2 FACTS & FIGURES 4 NEW & NOTEWORTHY 8 TRANSLATIONAL CLINICAL CARE 9 Rehabilitation’s Role in Value Based Medicine 12 Novel Treatment for Post-Stroke Muscle Stiffness 14 Rehabilitation Following Groundbreaking Face Transplant 16 Neuromodulation to Treat Shoulder Pain 18 Early Mobilization in the PICU 20 Brain Injury Research 23 Complex Case: NSTEMI Patient 24 ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES 29 LOCATIONS 30 LEADERSHIP Produced by the Office of Communications and Marketing, NYU Langone Medical Center Writer: Robert Fojut Design: Ideas On Purpose, www.ideasonpurpose.com Photography: Maria Aufmuth/TED; Karsten Moran Printing: Allied Printing Services, Inc. On the cover: Micro image of muscle fibers Message from the Chair Dear Colleagues and Friends: I am pleased to share with you the 2016 “Year in Review” from Rusk Rehabilitation. Our annual report highlights some of our team’s most significant achievements this year. In today’s world of healthcare reform, we can’t talk about any kind of achievement without asking two questions. First, did we improve patient outcomes? Second, did we control costs? These two issues define the essence of value-based care. At Rusk, we are focusing all our efforts on increasing the value of the care we provide. Our goal is to achieve better outcomes while lowering total costs. What are we doing to increase healthcare value? For one, we have helped pioneer a strategy that is delivering significant savings—early, intensive rehabilitation in critical care. -

2017 Jg U20 Boys

2017 JUNIOR GOLD CHAMPIONSHIPS July 20, 2017 - Cleveland, OH BOYS U20 DIVISION FINAL QUALIFYING STANDINGS 203 Advance to Advancers round - 64 to Final Advancers Round Block Grand Bowler Hometown SQUAD Prev Tot GM 13 GM 14 GM 15 GM 16 Total Total AVG +/- 1678 1 Tyler Gromlovits Junction City, KS 16 2671 210 179 243 198 830 3501 218.81 + 301 1571 2 Jeffery Mann West Lafayette, IN 15 2569 193 203 185 217 798 3367 210.44 + 167 637 3 Michael Martell Brooklyn, NY 7 2429 207 247 224 245 923 3352 209.50 + 152 864 4 Jake Farley Fort Thomas, KY 8 2558 221 211 157 190 779 3337 208.56 + 137 2745 5 David Hooper Greenville, SC 24 2519 189 213 218 190 810 3329 208.06 + 129 1766 6 Justin Wisler Davenport, FL 16 2501 184 195 242 200 821 3322 207.63 + 122 2602 7 Gage Stelling Apopka, FL 23 2453 220 186 205 240 851 3304 206.50 + 104 3757 8 Brent Boho Colgate, WI 32 2531 175 175 211 208 769 3300 206.25 + 100 1558 9 Aaron Major Brockton, MA 15 2455 212 238 196 187 833 3288 205.50 + 88 2721 10 Jacob Nimtz Loves Park, IL 24 2513 162 179 239 193 773 3286 205.38 + 86 425 11 Connor Egan East Northport, NY 5 2398 246 191 241 200 878 3276 204.75 + 76 408 12 Alec Karr Fremont, NE 5 2459 179 226 211 200 816 3275 204.69 + 75 2766 13 Wesley Low Palmdale, CA 24 2508 202 189 139 233 763 3271 204.44 + 71 691 14 Pete Vergos Apopka, FL 7 2477 235 200 195 160 790 3267 204.19 + 67 1663 15 Ryan Winters Livonia, MI 16 2531 161 190 188 190 729 3260 203.75 + 60 2611 16 Joseph Alvord South Lyon, MI 23 2317 226 244 210 258 938 3255 203.44 + 55 331 17 Joseph Grondin San Pedro, CA -

Download 1939-12-21

ig-a»' fc-ty^y^gSPy yC •St'^^i »..^»JV.^M.i- TKgamu 'library Eo3t Hni^eh Oona page Eight THE BEANPORD REVIEW, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 14, 1030 Movie Gmyed Church Notices THE POCKE TQPPS Finl Congregational Church 0/KNOWLTtiCE Oscar Boldtmann ot Short Beach Newsflashes From Hollywood; Kcv U. Kcnnclh Anthony, AIlnLitcr Scad, had an operation on his hand this week. He is in New Haven Hos Mtrxvi CIirtBtmaa Eleanor Powell fiolebratlng her Mmii Cttl^riatmaa Adults Bible Cla.s.s, Tuesday pital. birthday with a huge cako on the nights between Christmas and Eas set of "Broadway Melody of 1940", ter. Topic, "Tho Career and Signi Mrs. P. E. Kingston has returned ranforb 3^tjiehJ Fred Astaire and pianist Wal-1 ficance of Jesus." to her home In Delaware following AND EAST HAVEN NEWS tor Rulck proud of the fact that the December 24. Christmas play In a visit in Short Beach. studio wants their song, "There's Tho Industrial Basketball League Mr, and Mrs. Anthony Itkovlch Jr tho vestry by Congregational Play Mr. and Mrs. James Nichols, of VOL. Xn—NO. 37 Br.anford, Connecticut, Thursday, December 21, 1030 Price Five Cents \No Time Llkp The Present For have moved Into their now home on crs at 4 p. m. of 1030 and 1040 got under Thursday Coe Avenue, East Haven announce T Love," for a new Mickey Rooney- the Foxon road last Saturday. Mr Dec. 7th at the Y.M.C.A. Tho M.I.P. the marriage ot their daughter, Ann, Judy Garland film Jeanette Mac Ifkovlch is employed In our pattern Trinity Kiilscapal Church Donald talking over plans for her Co. -

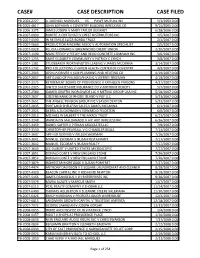

Case# Case Description Case Filed

CASE# CASE DESCRIPTION CASE FILED PB-2003-2227 A. MICHAEL MARQUES VS PAWT MUTUAL INS 5/1/2003 0:00 PB-2005-4817 JOHN BOYAJIAN V COVENTRY BUILDING WRECKING CO 9/15/2005 0:00 PB-2006-3375 JAMES JOSEPH V MARY TAYLOR DEVANEY 6/28/2006 0:00 PB-2007-0090 ROBERT A FORTUNATI V CREST DISTRIBUTORS INC 1/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0590 IN RE EMILIE LUIZA BORDA TRUST 2/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0663 PRODUCTION MACHINE ASSOC V AUTOMATION SPECIALIST 2/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0928 FELICIA HOWARD V GREENWOOD CREDIT UNION 2/20/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1190 MARC FEELEY V FEELEY AND REGO CONCRETE COMPANY INC 3/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1255 SAINT ELIZABETH COMMUNITY V PATRICK C LYNCH 3/8/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1381 STUDEBAKER WORTHINGTON LEASING V JAMES MCCANNA 3/14/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1742 PRO COLLECTIONS V HAVEN HEALTH CENTER OF COVENTRY 4/9/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2043 JOSHUA DRIVER V KLM PLUMBING AND HEATING CO 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2057 ART GUILD OF PHILADELPHIA INC V JEFFREY FREEMAN 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2175 RETIREMENT BOARD OF PROVIDENCE V KATHLEEN PARSONS 4/27/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2325 UNITED STATES FIRE INSURANCE CO V ANTHONY ROSCITI 5/7/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2580 GAMER GRAFFIX WORLDWIDE LLC V METINO GROUP USA INC 5/18/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2637 CITIZENS BANK OF RHODE ISLAND V PGF LLC 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2651 THE ANGELL PENSION GROUP INC V JASON DENTON 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2835 PORTLAND SHELLFISH SALES V JAMES MCCANNA 6/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2925 DEBRA A ZUCKERMAN V EDWARD D FELDSTEIN 6/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3015 MICHAEL W JALBERT V THE MKRCK TRUST 6/13/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3248 WANDALYN MALDANADO -

Labor Leaders Irked, Want New Strike Laws

WEATHER Per *J Fair today awl toalgbt. High today, M. Low tonight. 48. Part- SHadyiidz 14MH0 ly dandy lemorrow with • Ufa of M. See page 2. iMUtfl Dttnr. Mondur thremli •atma u Meosl CUM Kttut RED BANK, N. J., TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 1959 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE VOLUME LXXXII NO. 61 at UM POM OIDCI at 11*4 auk. M. outer tli* Act «l Kates S. UK. Coiieil H«a S Day Double Sessions Seek New School Legislation, Labor Leaders Irked, Seen for Regional County Official Tells MatawanWant New Strike Laws FREEHOLD - Site location for, MATAWAN — County School Rap Handling an additional high school, and Superintendent Earl B. Garrison plant for complete double ses- last night called on the Matawan sions for next year will be an- school dUtrict to Join with other Of Steel Crisis;! nounced In the near future, It consolidated districts in the state was nude known at latt night's to press for new legislation "as Regional Board of Education the best, easiest and fastest way" Workers Back meeting. to solve the school problem here. Board president Vincent Foy The occasion was a meeting in WASHINGTON (AP) «- (Freehold Township) reported the high school attended by the AFL-CIO leaders, sharply that the board has been studying Borough Council, the Township critical of President Eisen- for several months possible loca- Committee, the Board of Educa- hower's handling of, tht tion* for additional facilities to tion, the Cltiiens Committee for steel strike, mapped pliii the present school, which now Better Matawan Borough Schools houses 1,(96 students. -

Our First Quarter Century of Achievement ... Just the Beginning I

NASA Press Kit National Aeronautics and 251hAnniversary October 1983 Space Administration 1958-1983 >\ Our First Quarter Century of Achievement ... Just the Beginning i RELEASE ND: 83-132 September 1983 NOTE TO EDITORS : NASA is observing its 25th anniversary. The space agency opened for business on Oct. 1, 1958. The information attached sumnarizes what has been achieved in these 25 years. It was prepared as an aid to broadcasters, writers and editors who need historical, statistical and chronological material. Those needing further information may call or write: NASA Headquarters, Code LFD-10, News and Information Branch, Washington, D. C. 20546; 202/755-8370. Photographs to illustrate any of this material may be obtained by calling or writing: NASA Headquarters, Code LFD-10, Photo and Motion Pictures, Washington, D. C. 20546; 202/755-8366. bQy#qt&*&Mary G. itzpatrick Acting Chief, News and Information Branch Public Affairs Division Cover Art Top row, left to right: ffComnandDestruct Center," 1967, Artist Paul Calle, left; ?'View from Mimas," 1981, features on a Saturnian satellite, by Artist Ron Miller, center; ftP1umes,*tSTS- 4 launch, Artist Chet Jezierski,right; aeronautical research mural, Artist Bob McCall, 1977, on display at the Visitors Center at Dryden Flight Research Facility, Edwards, Calif. iii OUR FIRST QUARTER CENTER OF ACHIEVEMENT A-1 -3 SPACE FLIGHT B-1 - 19 SPACE SCIENCE c-1 - 20 SPACE APPLICATIQNS D-1 - 12 AERONAUTICS E-1 - 10 TRACKING AND DATA ACQUISITION F-1 - 5 INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS G-1 - 5 TECHNOLOGY UTILIZATION H-1 - 5 NASA INSTALLATIONS 1-1 - 9 NASA LAUNCH RECORD J-1 - 49 ASTRONAUTS K-1 - 13 FINE ARTS PRQGRAM L-1 - 7 S IGN I F ICANT QUOTAT IONS frl-1 - 4 NASA ADvIINISTRATORS N-1 - 7 SELECTED NASA PHOTOGRAPHS 0-1 - 12 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, D.C. -

A Finding Aid to the Architectural League of New York Records, 1880S-1974, Bulk 1927-1968, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Architectural League of New York Records, 1880s-1974, bulk 1927-1968, in the Archives of American Art Sarah Haug Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care and Preservation Fund September 21, 2011 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Administrative Files, 1889-1969................................................................ 6 Series 2: Committee Records, 1887-1974............................................................. 10 -

CSI in the News

CSI in the News August 2012 csitoday.com/in-the-news Archive csitoday.com/publication/csi-in-the-news COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND The City University of New York Table of Contents Ads . 3 Arts & Events . 5 Faculty & Staff . 8 Sports . 45 Stories . 55 Students & Alumni . 77 ADS Page 3 of 101 Page 4 of 101 Arts & Events Page 5 of 101 Review: Staten Island Philharmonic's 'Summer Strings' at Noble Maritime Monday, August 13, 2012, 6:18 PM Michael J. Fressola By STATEN ISLAND, NY -- Veteran Island cellist Madeline Casparie was the hard- working center this past Sunday of "Summer Strings," a concert staffed by string musicians affiliated with the Staten Island Philharmonic. She had "a lot of work to do," an amusing understatement by double bass Bliss Michelson, who had to trade his instrument at one point for castanets. Conversely, guitarist Edward Brown had the least to do — he was in just one piece — the Quintet in D Major, the Fandango of Luigi Bioccherini. In his contribution of lovely Spanish figures, the guitar becomes the leading dancer of the music. The piece, well played throughout, with cool, supple playing by the cellist, formed the exciting finale of the afternoon concert, presented in the nicely-chilled “hyphen” of the Noble Maritime Collection on the grounds of the Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden. View full size ADVANCE FILE PHOTO Acoustically, the space is kind to a small Bliss Michelson all-string group (but less kind to larger ensembles as some past presentations have indicated). Page 6 of 101 The program opened with unusual items, the Divertimento Opus 3 of Johnan Kvandal, the underexposed Norwegian composer who deserves more playing time than he seems to get in this country. -

Junta Takes Action to Legalize Coup

DfstrflauTton Wortfcer Today „ tUt today «ad Umtyk Ugk WDBANK 17,750 •hdtt 71; low, M. berating CMWBMW tomorrow with rain* ••• *•• weather pig* X MONDAY THKOUOIMIMY-tST. UH SH I-0010 tuuM duly. 5ton4»j tntouis maw. Mcoca Clu> 7c PER COPY "«PER WEEK VOL 83, NO. 225 nil al Ktd Bank and ti Aadltlml Ktlltat RED BANK, N. J., WEDNESDAY, MAY 17, 1961 /u run wr» By CARRIER PAGE ONE Vouchers Questioned Road Plans Junta Takes Action Attorney Fees Revision Set HOLMDEL — Plans for im- of the program may be eliminat- Are Disputed provements to roads in the Bell ed to keep costs close to the Labs area will be substantially original estimates, which have To Legalize Coup KEANSBURG - At the insist- marked, looking at Mr. Collie revised, >as a result of a meet- varied from $700,000 to $830,000. ence of Councilman Louis Col- hio. ing last night between officials Rt. 34 Connection lichio, the governing body last Mr. Collichio indicated that, for of the governing body and Bell The township committee is now night held up payment of seven the most part, he was challenging Labs. considering the possibility, he vouchers from borough attorney two vouchers, one for $3,500, in said, of putting a road through Township Attorney Lawrence A, Rebel Howard W. Roberts, for legal connection with legal services which would connect to Rt. 34. Carton Jr, told The Register, fees. rendered in the Pivnick motel At the same time, Bell officials however, that the nature of the transaction, and another for said last night that there is no Mr. -

Candidates Seeking Their Party's Support in to a Guaranteed Cease-Fire in the Owned and Operated by Levitt the Former State Superior Court April 18 Primary

Distribution Today Weather Partly cloudy today, chance ol 17,975 •bowers; high, Sop. Partly cloudy BED BANK tonight; low, 30s. Partly cloudy tomorrow; high, 50s. See weather 1 Independent Daily f SH I -0010 page 2, ( HONDAYTHKuaurUDAY-MSTm J 35c PER WEEK Turned dally. Monday tarouiB Friday. Second Clftss Poitaze 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE VOL. 83, NO. 197 Paid »t Red Bank and at Additional Mailing Ollicti. RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, APRIL 6, 1961 BY CARRIER To Cut Lot Size For $25 Million JFK, Macmillan Project By Levitt Map Laos Strategy 1,300 Houses Mitchell Says Planned for Nixon Will Help Hughes Airs ELIZABETH (AP) — .lamer Leaders 500-Ac're Site P. Mitchell says former Vice President Richard M. Nixon Intentions MATAWAN TOWNSHIP will campaign for him If he — The Planning Board and wins the Republican guberna- On Platform Reported Township Committee torial nomination. LONG BRANCH - Richard J. agreed last night to dowrv Mitchell disclosed yesterday Hughes, organization Democratic that Nixon had confirmed a candidate for governor, told more grade lot size to 7,500 Hopeful commitment to come to New .nan 250 Monmouth County par- square feet in the south Jersey made before Mitchell isans last night he will take a entered the primary. PROPOSED LOCATION—The shaded area in this pic- strong position of leadership in west section of town for drafting the state Democratic WASHINGTON (AP) — Mitchell, former labor secre- ture is where the Riverdale Swim Club it proposed in a 1,300-house development tary, said he understood Nixon ilatform after the primary. President Kennedy and by Levitt and Sons, Inc.