Martin Helmchen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Landmarks in New York

MUSICAL LANDMARKS IN NEW YORK By CESAR SAERCHINGER HE great war has stopped, or at least interrupted, the annual exodus of American music students and pilgrims to the shrines T of the muse. What years of agitation on the part of America- first boosters—agitation to keep our students at home and to earn recognition for our great cities as real centers of musical culture—have not succeeded in doing, this world catastrophe has brought about at a stroke, giving an extreme illustration of the proverb concerning the ill wind. Thus New York, for in- stance, has become a great musical center—one might even say the musical center of the world—for a majority of the world's greatest artists and teachers. Even a goodly proportion of its most eminent composers are gathered within its confines. Amer- ica as a whole has correspondingly advanced in rank among musical nations. Never before has native art received such serious attention. Our opera houses produce works by Americans as a matter of course; our concert artists find it popular to in- clude American compositions on their programs; our publishing houses publish new works by Americans as well as by foreigners who before the war would not have thought of choosing an Amer- ican publisher. In a word, America has taken the lead in mu- sical activity. What, then, is lacking? That we are going to retain this supremacy now that peace has come is not likely. But may we not look forward at least to taking our place beside the other great nations of the world, instead of relapsing into the status of a colony paying tribute to the mother country? Can not New York and Boston and Chicago become capitals in the empire of art instead of mere outposts? I am afraid that many of our students and musicians, for four years compelled to "make the best of it" in New York, are already looking eastward, preparing to set sail for Europe, in search of knowledge, inspiration and— atmosphere. -

Piano Trio, Op. 1, No. 1 · Divertimento for Cello and Orchestra

LSC-2770 STEREO HEIFETZ-PIATIGORSKY CONCERTS with Jacob Lateiner and Guests BEETHOVEN Piano Trio, Op. 1, No. 1 HAYDN Divertimento for Cello and Orchestra ROZSA Tema con Vatiazioni (for Violin, Cello and Orchestra RCA VICTOR RED SEALE DYNAGROOVE RECORDING Si a ee vsti eta Aha Sic CYL Sen a «Rese OOP ET ED RI OE eee” SL ORE RO SE rises MP OR tet et ee Mono LM-2770 Stereo LSC-2770 HEIFETZ-PIATIGORSKY CONCERTS with Jacob Lateiner and Guests BEETHOVEN Piano Trio, Op. 1, No. 1 HAYDN Divertimento for Cello and Orchestra ROZSA Tema con Variazioni (For Violin, Cello and Orchestra) Jascha Heifetz, Violinist + Gregor Piatigorsky, Cellist Jacob Lateiner, Pianist Recording Director: John F. Pfeiffer « Recording Engineers: Ivan Fisher and John Norman several isolated movements from the Divertimenti. For the 1963 Heifetz- For many years Jascha Heifetz and Gregor Piatigorsky Piatigorsky Concerts in Los Angeles, Mr. Piatigorsky requested Ingolf Dahl had enjoyed playing chamber music in the privacy of their to orchestrate three of these movements to form a little concerto for cello homes, a happy and noble form of music-making in which and orchestra. Mr. Dahl made only minor changes in the solo part except they were often joined by similarly addicted colleagues. to delete a few measures in the last movement to form an orchestral tutti. Eventually, in the summer of 1961, they decided to share He orchestrated in the Haydn manner for oboes and strings and in the their musical experiences and pleasures with music-lovers of second movement restored Haydn’s original harmonization. If this perform- the surrounding communities. -

Mercredi 25 Avril 2012 Nora Gubisch | Ensemble Intercontemporain | Alain Altinoglu

Roch-Olivier Maistre, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Mercredi 25 avril 2012 avril 25 Mercredi | Mercredi 25 avril 2012 Nora Gubisch | Ensemble intercontemporain | Alain Altinoglu Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.citedelamusique.fr Altinoglu | Alain Gubisch | Ensemble intercontemporain Nora 2 MERCREDI 25 AVRIL – 20H Salle des concerts Lu Wang Siren Song Igor Stravinski Huit Miniatures instrumentales Concertino pour douze instruments Maurice Ravel Trois Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé entracte Marc-André Dalbavie Palimpseste Luciano Berio Folk Songs Nora Gubisch, mezzo-soprano Ensemble intercontemporain Alain Altinoglu, direction Diffusé en direct sur les sites Internet www.citedelamusiquelive.tv et www.arteliveweb.com, ce concert restera disponible gratuitement pendant trois mois. Il est également retransmis en direct sur France Musique. Coproduction Cité de la musique, Ensemble intercontemporain. Fin du concert vers 22h15. 3 Lu Wang (1982) Siren Song Composition : 2008. Création : 5 avril 2008 à New York, Merkin Concert Hall, par l’International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), sous la direction de Matt Ward. Effectif : flûte / flûte piccolo, clarinette en si bémol / clarinette en mi bémol / clarinette basse – cor, trompette – piano – harpe – percussions – violon, alto, violoncelle. Éditeur : inédit. Durée : environ 7 minutes. Cette pièce peut être vue comme un court opéra. Elle utilise la translittération d’un ancien dialecte de Xi’an, ma ville natale, extrêmement puissant et musical qui, dans le parlé/chanté, se déploie en intervalles démesurés et en glissandi. J’avais été particulièrement fascinée par une voix que j’entendis chez un conteur qui chantait dans ce dialecte : c’était la voix sèche, comme affolée et pourtant très séduisante d’un vieil eunuque. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

// BOSTON T /?, SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THURSDAY B SERIES EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 wgm _«9M wsBt Exquisite Sound From the palace of ancient Egyp to the concert hal of our moder cities, the wondroi music of the harp hi compelled attentio from all peoples and a countries. Through th passage of time man changes have been mac in the original design. Tl early instruments shown i drawings on the tomb < Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C were richly decorated bv lacked the fore-pillar. Lato the "Kinner" developed by tl Hebrews took the form as m know it today. The pedal hai was invented about 1720 by Bavarian named Hochbrucker an through this ingenious device it b came possible to play in eight maj< and five minor scales complete. Tods the harp is an important and familij instrument providing the "Exquisi* Sound" and special effects so importai to modern orchestration and arrang ment. The certainty of change mak< necessary a continuous review of yoi insurance protection. We welcome tl opportunity of providing this service f< your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. HENRY B. CABOT President TALCOTT M. BANKS Vice-President JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer PHILIP K. ALLEN E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ABRAM BERKOWITZ EDWARD M. KENNEDY THEODORE P. -

Orchestre De Paris Asume El Papel De Asesor Artístico En 2020/2021 Y Será Su Próximo Director Musical a Partir De Septiembre De 2022

70 Festival de Granada Biografías Klaus Mäkelä Klaus Mäkelä es director principal y asesor artístico de la Filarmónica de Oslo. Con la Orchestre de Paris asume el papel de asesor artístico en 2020/2021 y será su próximo director musical a partir de septiembre de 2022. Es, además, director invitado principal de la Orquesta Sinfónica de la Radio Sueca y director artístico del Festival de Música de Turku. Como artista exclusivo de Decca Classics, Klaus Mäkelä ha grabado el ciclo completo de sinfonías de Sibelius con la Filarmónica de Oslo como primer proyecto con el sello, que será editado en la primavera de 2022. Klaus Mäkelä inaugura la temporada 2021/2022 de la Filarmónica de Oslo este mes de agosto con un concierto especial interpretando el Divertimento de Bartók, el Concierto para piano nº 1 con Yuja Wang como solista, dos obras de estreno del compositor noruego Mette Henriette y Lemminkäinen de Sibelius. Ofrecerá un repertorio de similar amplitud durante su segunda temporada en Oslo., incluyendo las grandes obras corales de J. S Bach, Mozart y William Walton, la Sinfonía nº 3 de Mahler y las nº 10 y 14 de Shostakóvich con los solistas Mika Kares y Asmik Grigorian. Entre las obras contemporáneas y de estreno se incluyen composiciones de Sally Beamish, Unsuk Chin, Jimmy Lopez, Andrew Norman y Kaija Saariaho. En la primavera de 2022, Klaus Mäkelä y la Filarmónica de Oslo interpretarán las sinfonías completas de Sibelius en la Wiener Konzerthaus y la Elbphilharmonie de Hamburgo, y en gira por Francia y el Reino Unido. Con la Orchestre de Paris, visitará los festivales de verano de Granada y Aix-en- Provence. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

Week 13 Andris Nelsons Music Director

bernard haitink conductor emeritus seiji ozawa music director laureate 2014–2015 Season | Week 13 andris nelsons music director season sponsors Table of Contents | Week 13 7 bso news 17 on display in symphony hall 18 bso music director andris nelsons 20 the boston symphony orchestra 23 a brief history of the bso 29 this week’s program Notes on the Program 30 The Program in Brief… 31 Wolfgang Amadè Mozart 37 Anton Bruckner 49 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artist 53 Lars Vogt 56 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 83 symphony hall information the friday preview talk on january 16 is given by elizabeth seitz of the boston conservatory. program copyright ©2015 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo of Andris Nelsons by Marco Borggreve cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate 134th season, 2014–2015 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. William F. Achtmeyer, Chair • Paul Buttenwieser, President • Carmine A. Martignetti, Vice-Chair • Arthur I. Segel, Vice-Chair • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chair • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer David Altshuler • George D. Behrakis • Ronald G. Casty • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Diddy Cullinane • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Susan Hockfield • Barbara Hostetter • Charles W. -

CASADESUS the Complete French Columbia Recordings

THE FRENCH PIANO SCHOOL ROBERT CASADESUS The complete French Columbia recordings ROBERT CASADESUS The complete French Columbia recordings 1928–1939 including the first release of the 1931 Mozart ‘Coronation’ Concerto COMPACT DISC 1 (78.15) SCARLATTI 11 Sonatas 1. Sonata in D major, Kk430 (L463) .................................................................. (1.51) 2. Sonata in A major, Kk533 (L395) .................................................................. (2.23) 3. Sonata in D major, Kk23 (L411) ................................................................... (2.29) 4. Sonata in B minor, Kk377 (L263) .................................................................. (1.17) 5. Sonata in D major, Kk96 (L465) ................................................................... (4.10) 6. Sonata in D minor, Kk9 (L413) ..................................................................... (1.36) 7. Sonata in G major, Kk125 (L487) .................................................................. (2.00) 8. Sonata in B minor, Kk27 (L449) ................................................................... (1.54) 9. Sonata in G major, Kk14 (L387) ................................................................... (1.53) 10. Sonata in E minor, Kk198 (L22) ................................................................... (2.10) 11. Sonata in G major, Kk13 (L486) ................................................................... (1.58) Recorded on 15 June 1937; matrices CLX 1952-1Tracks 1,2, 1953-33,4, 1954-15, 1955-36,7, 1956-38,9, -

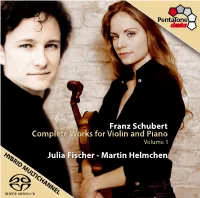

Franz Schubert Complete Works for Violin and Piano Julia

Volume 1 Franz Schubert Complete Works for Violin and Piano Julia Fischer - Martin Helmchen HYBRID MUL TICHANNEL Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) Schubert composed his Violin Sonatas Complete Works for Violin and Piano, Volume 1 in 1816, at a time in life when he was obliged he great similarity between the first to go into teaching. Actually, the main Sonata (Sonatina) for Violin and Piano in D major, D. 384 (Op. 137, No. 1) Tmovement (Allegro molto) of Franz reason was avoiding his military national 1 Allegro molto 4. 10 Schubert’s Sonata for Violin and Piano in service, rather than a genuine enthusiasm 2 Andante 4. 25 D major, D. 384 (Op. posth. 137, No. 1, dat- for the teaching profession. He dedicated 3 Allegro vivace 4. 00 ing from 1816) and the first movement of the sonatas to his brother Ferdinand, who Sonata (Sonatina) for Violin and Piano in A minor, D. 385 (Op. 137, No. 2) the Sonata for Piano and Violin in E minor, was three years older and also composed, 4 Allegro moderato 6. 48 K. 304 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart must although his real interest in life was playing 5 Andante 7. 29 have already been emphasised hundreds the organ. 6 Menuetto (Allegro) 2. 13 of times. The analogies are more than sim- One always hears that the three early 7 Allegro 4. 36 ply astonishing, they are essential – and at violin sonatas were “not yet true master- the same time, existential. Deliberately so: pieces”. Yet just a glance at the first pages of Sonata (Sonatina) for Violin and Piano in G minor, D. -

Martynas Levickis (* 1990) Litauische Volkslieder in Arrangements Für Akkordeon »Rūta Žalioj« (Die Grüne Straße) »Beauštanti Aušrelė« (Die Morgendämmerung Bricht An)

Bach und Baltikum SO 29. MRZ 2020 | KULTURPALAST PROGRAMM Pēteris Vasks (* 1946) »Cantus ad pacem« für Orgel solo (1984) Martynas Levickis (* 1990) Litauische Volkslieder in Arrangements für Akkordeon »Rūta žalioj« (Die grüne Straße) »Beauštanti aušrelė« (Die Morgendämmerung bricht an) Veli Kujala (* 1976) »Photon« für Orgel und Akkordeon (2015) Fantasie und Fuge a-Moll BWV 561 für Orgel (Arrangement für Akkordeon von Martynas Levickis) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750) »Pièce d'Orgue« – Fantasie G-Dur BWV 572 für Orgel (um 1728) Fantasie und Fuge a-Moll BWV 561 für Orgel (Arrangement für Akkordeon von Martynas Levickis) Pēteris Vasks »Veni Domine« für gemischten Chor und Orgel (2018) Iveta Apkalna | Orgel PALASTORGANISTIN Martynas Levickis | Akkordeon Philharmonischer Chor Dresden Gunter Berger | Leitung Riga, die lettische Hauptstadt 2 JOHANNA ANDREA WOLTER Komponieren, um die Welt im Gleichgewicht zu halten Pēteris Vasks CANTUS AD PACEM FÜR ORGEL SOLO Pēteris Vasks wurde am 16. April 1946 in Aizpute (Lettland) als Sohn eines in Lettland bekannten baptistischen Pastors geboren. Er bekam zunächst Musik- unterricht an der örtlichen Musikschule, begann bald zu komponieren und erhielt Pēteris Vasks eine Ausbildung als Kontrabassist an der Emīls Dārziņš-Musikschule in Riga. Da ihm der Zugang zu einem Studium Ab 1961 war er Mitglied verschiedener an einer Musikhochschule in Lettland Sinfonie- und Kammerorchester: beim zunächst verwehrt blieb, wich er ins Philharmonischen Orchester von Litauen liberalere Litauen aus, besuchte 1964 bis (1966 – 1969), beim Philharmonischen 1970 die Kontrabassklasse von Vytautas Kammerorchester von Lettland (1969 – Sereika am Litauischen Konservatorium 1970) und beim Lettischen Rundfunk- in Vilnius und leistete anschließend und Fernsehorchester (1971 – 1974). seinen Militärdienst in der Sowjetarmee. -

La Recepción Temprana De Wagner En Estados Unidos: Wagner En La Kleindeutschland De Nueva York, 1854-1874

Resonancias vol. 19, n°35, junio-noviembre 2014, pp. 11-24 La recepción temprana de Wagner en Estados Unidos: Wagner en la Kleindeutschland de Nueva York, 1854-1874 F. Javier Albo Georgia State University, Atlanta, USA. [email protected] Resumen Este trabajo se centra en la recepción de la música de Richard Wagner, limitado a un marco geográfico específico, el de la ciudad de Nueva York –en concreto el distrito alemán de la ciudad, conocido como Kleindeutschland– y temporal, el comprendido entre la primera ejecución documentada de una obra de Wagner en la ciudad, en 1854, y la definitiva entronización del compositor como legítimo representante de la tradición musical alemana a partir del estreno de Lohengrin en la Academy of Music, en 1874. Se destaca la labor de promoción a cargo de los emigrantes alemanes, en su papel de mediadores, en los años 50 y 60 del siglo XIX, una labor fundamental ya que gracias a ella germinó la semilla del culto a Wagner que eclosionaría durante la Gilded Age, la “Edad dorada” del desarrollo económico y artístico finisecular, que afectó a todo el país pero de manera especial a Nueva York. Asimismo, se incluye una aproximación a la recepción en la crítica periodística neoyorquina durante el periodo en cuestión. Palabras clave: Wagner; Recepción temprana en Nueva York; Músicos alemanes y emigración, 1850-1875; Crítica periodística. Abstract This study discusses the early reception of Richard Wagner’s music in New York, starting with the first documented performance of a work by Wagner in the city, in 1854, and the momentous production of Lohengrin at the Academy of Music, in 1874. -

Richard Wagner

RICHARD WAGNER OVERTURES & PRELUDES FRANKFURT RADIO SYMPHONY ANDRÉS OROZCO-ESTRADA RICHARD WAGNER 1 DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER 1813–1883 WWV 63: Overture / Ouvertüre 10:13 OVERTURES & PRELUDES 2 LOHENGRIN OUVERTÜREN & VORSPIELE WWV 75: Prelude to Act I / Vorspiel zum 1. Akt 9:03 3 & 4 TRISTAN UND ISOLDE FRANKFURT RADIO SYMPHONY WWV 90: Prelude / Vorspiel 11:57 hr-Sinfonieorchester Liebestod 7:55 ANDRÉS OROZCO-ESTRADA 5 PARSIFAL Music Director / Chefdirigent WWV 111: Prelude / Vorspiel 14:52 6 TANNHÄUSER WWV 70: Overture / Ouvertüre 15:02 7 RIENZI, DER LETZTE DER TRIBUNEN WWV 49: Overture / Ouvertüre 12:03 Total time / Gesamtspielzeit 81:35 Live Recording: August 22nd, 2014 (3&4); June 26th, 2015 (5&6); June 25th, 2017 (1&2) · Recording Location: Basilika, Kloster Eberbach, Germany · Recording producers: Christoph Claßen (3&4) & Philipp Knop (1-2 & 5-6) Recording engineers: Thomas Eschler (3-6), Andreas Heynold (1&2) · Executive Producer: Michael Traub · Photo Andrés Orozco-Estrada: © hr/Martin Sigmund · Photo Frankfurt Radio Symphony: © hr/Ben Knabe · Artwork: [ec:ko] communications Co-production with Hessischer Rundfunk · P & C 2019 Sony Music Entertainment Germany GmbH of the nineteenth century. This was the first time that Wagner – who, as always, wrote his RICHARD WAGNER own libretto – found the motifs and themes that he was to make quintessentially his own: OVERTURES & PRELUDES the longing for death, a woman’s willingness to sacrifice her own life out of compassion, the hero as restless outsider, death resulting from love and the idea of redemption. In his essay “On the Overture”, which he first published in French in January 1841, the then The Overture dates from November 1841 and was the last part of the score to be written twenty-seven-year-old Wagner summed up his ideas on what an operatic overture should – in this regard Wagner adopted contemporary practice rather than the approach that he ideally be like.