Violent Crime and Fragility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map of Corruption in Yemen: Influential Parties

Map of Corruption in Yemen: Influential Parties Dr. Yehya Salih Mohsin Yemen Observatory for Human Rights (YOHR) 2010 Contents Foreword Preface (Anecdotes on corruption in Yemen) Introduction Chapter One: Concepts and levels of corruption: Its indicators and mechanisms in Yemen - Concepts and definitions of corruption - Levels and forms of corruption - Destructive impacts of corruption - Indicators of corruption in Yemen - The foremost mechanisms of corruption in Yemen - The private sector adapts to corrupt relationships - The government and the World Bank are partners in obscuring and distorting data - The Supreme National Anti-Corruption Commission: Destructive corruption and poor performance Chapter Two: The political economy of corruption in Yemen - Yemen on the verge of failed statehood - When corruption becomes an institution - The tribal military alliance – a pillar of the corrupt authority - Absolute authority – a support for the institution of corruption - Hereditary rule and the politicisation of public service - Corruption: the great sponsor of terrorism Chapter Three: Corruption in the oil sector in Yemen - The nature of the socio-economic circumstances - The major deficiencies in the oil sector - Mechanisms and forms of corruption in the oil sector: 4 • Corruption through “additional credits” 5 • Corruption through smuggling of oil derivatives 12 • Other forms of corruption in the oil sector 16 Chapter Four: Corruption in Yemen: A field study - Numerical data from the field studies (questionnaire) - Analysis of the results -

In Yemen, 2012

Updated Food Security Monitoring Survey Yemen Final Report September 2013 Updated Food Security Monitoring Survey (UFSMS), Yemen, Sept. 2013 Foreword Food insecurity and malnutrition are currently among the biggest challenges facing Yemen. Chronic malnutrition in the country is unacceptably high – the second highest rate in the world. Most of Yemen’s governorates are at critical level according to classifications by the World Health Organization. While the ongoing social safety net support provided by the government’s Social Welfare Fund has prevented many poor households from sliding into total destitution, WFP’s continued humanitarian aid operations in collaboration with government and partners have helped more than 5 million severely food insecure people to manage through difficult times in 2012 and 2013. However, their level of vulnerability has remained high, as most of those food insecure people have been forced to purchase food on credit, become more indebted and to use other negative coping strategies - and their economic condition has worsened during the past two years. Currently, about 10.5 million people in Yemen are food insecure, of whom 4.5 million are severely food insecure and over 6 million moderately food insecure. The major causes of the high levels of food insecurity and malnutrition include unemployment, a reduction in remittances, deterioration in economic growth, extreme poverty, high population growth, volatility of prices of food and other essential commodities, increasing cost of living including unaffordable health expenses, and insecurity. While the high level of negative coping strategies being used by food-insecure households continues, the food security outlook does not look better in 2014, as the major causes of current food insecurity are likely to persist in the coming months, and may also be aggravated by various factors such as uncertainties in the political process, declining purchasing power, and continued conflicts and the destruction of vital infrastructure including oil pipelines and electricity power lines. -

Combating Corruption in Yemen

Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: COMBATING CORRUPTION IN YEMEN By: The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies November 2018 COMBATING CORRUPTION IN YEMEN Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: COMBATING CORRUPTION IN YEMEN By: The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies November 2018 This white paper was prepared by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, in coordination with the project partners DeepRoot Consulting and CARPO – Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient. Note: This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union and the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Yemen. The recommendations expressed within this document are the personal opinions of the author(s) only, and do not represent the views of the Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies, DeepRoot Consulting, CARPO - Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient, or any other persons or organizations with whom the participants may be otherwise affiliated. The contents of this document can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Yemen. Co-funded by the European Union Photo credit: Claudiovidri / Shutterstock.com Rethinking Yemen’s Economy | November 2018 2 COMBATING CORRUPTION IN YEMEN TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 3 Acronyms 4 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 8 State Capture Under Saleh 10 Origins of Saleh’s Patronage System 10 Main Beneficiaries of State Capture and Administrative Corruption 12 Maintaining -

Struggle for Citizenship.Indd

From the struggle for citizenship to the fragmentation of justice Yemen from 1990 to 2013 Erwin van Veen CRU Report From the struggle for citizenship to the fragmentation of justice FROM THE STRUGGLE FOR CITIZENSHIP TO THE FRAGMENTATION OF JUSTICE Yemen from 1990 to 2013 Erwin van Veen Conflict Research Unit, The Clingendael Institute February 2014 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. Clingendael Institute P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/ Table of Contents Executive summary 7 Acknowledgements 11 Abbreviations 13 1 Introduction 14 2 Selective centralisation of the state: Commerce and security through networked rule 16 Enablers: Tribes, remittances, oil and civil war 17 Tools: Violence, business and religion 21 The year 2011 and the National Dialogue Conference 26 The state of justice in 1990 and 2013 28 3 Trend 1: The ‘instrumentalisation’ of state-based justice 31 Key strategies in the instrumentalisation of justice 33 Consequences of politicisation and instrumentalisation 34 4 Trend 2: The weakening of tribal customary law 38 Functions and characteristics of tribal law 40 Key factors that have weakened tribal law 42 Consequences of weakened tribal law 44 Points of connection -

Yemen's Solar Revolution: Developments, Challenges, Opportunities

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ansari, Dawud; Kemfert, Claudia; al-Kuhlani, Hashem Research Report Yemen's solar revolution: Developments, challenges, opportunities DIW Berlin: Politikberatung kompakt, No. 142 Provided in Cooperation with: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Suggested Citation: Ansari, Dawud; Kemfert, Claudia; al-Kuhlani, Hashem (2019) : Yemen's solar revolution: Developments, challenges, opportunities, DIW Berlin: Politikberatung kompakt, No. 142, ISBN 978-3-946417-33-0, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/206954 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under -

Rasgas, Petronet Sign LNG Supply Deal for India

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Sheikh Salman manifesto aims to rise INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2, 20 COMMENT 18, 19 ARAB WORLD 3, 4 BUSINESS 1-8 FIFA from Qatar budget ‘focusing’ 17,488.96 10,429.36 37.12 INTERNATIONAL 5-16 CLASSIFIED 5 -114.91 -06.61 +1.42 ISLAM 17 SPORT 1-8 on sustainable growth ‘ashes’ -0.65% -0.06% +0.52% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 FRIDAY Vol. XXXVI No. 9954 January 1, 2016 Rabia I 21, 1437 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Hopes on the horizon Blaze engulfs GULF TIMES WISHES ITS Dubai hotel READERS A HAPPY NEW YEAR near world’s In brief tallest tower Reuters QATAR | Offi cial Dubai Emir exchanges ire engulfed a 63-storey sky- New Year greetings scraper in downtown Dubai near HH the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Fthe world’s tallest building last Hamad al-Thani exchanged cables of night, but the block was successfully congratulations with Their Majesties evacuated and there were only light and Highnesses the leaders of injuries, the emirate’s police chief friendly countries on the occasion said. of the New Year, wishing them the Tongues of fl ame shot skywards best of health and happiness and The sun sets on 2015 as people enjoy a pleasant winter evening in Doha’s Aspire Park yesterday. An eventful year for Qatar from one side of the luxury Address their peoples further progress and and the rest of the world has gone down in history. The New Year, 2016, brings with it many hopes and challenges. -

Entre La Inestabilidad Y El Colapso, Yemen, El Fracaso Del Proyecto Republicano

MASTER EN RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES Departamento de Derecho Internacional Público y Relaciones Internacionales Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociología UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Entre la inestabilidad y el colapso, Yemen, el fracaso del proyecto republicano Moisés García Corrales Trabajo de investigación de final de Máster dirigido por la profesora Paloma González del Miño Yemen, el fracaso del proyecto republicano__________________________________________________ ENTRE LA INESTABILIDAD Y EL COLAPSO: YEMEN, EL FRACASO DEL PROYECTO REPUBLICANO Introducción metodológica Identificación del objeto de investigación Motivación del tema de estudio Delimitación temporal Formulación del tema de estudio Formulación de la hipótesis de partida I. El sistema político y la gobernanza en la República de Yemen 1. INTRODUCCIÓN HISTÓRICA 1.1. La división de Yemen: un país, dos naciones 1.2. La unificación de Yemen: el proyecto republicano 2. LA REALIDAD TRIBAL FRENTE A LA REALIDAD ESTATAL 3. EL PROYECTO REPUBLICANO Y SU DERIVA POLÍTICA 3.1. El constitucionalismo en la República de Yemen 3.1.1. El sistema constitucional y sus reformas 3.1.2. Los derechos y deberes ciudadanos 3.2. El Gobierno y la gobernanza en la República de Yemen 3.2.1. El sistema de partidos 3.2.2. La sucesión presidencial Yemen, el fracaso del proyecto republicano__________________________________________________ 3.2.3. El papel de las Fuerzas Armadas 3.2.4. La descentralización 3.2.5. La lucha contra la corrupción II. El fracaso del proyecto republicano de unificación 4. LOS CONFLICTOS DESEQUILIBRANTES DE LA REPÚBLICA DE YEMEN 4.1. El borde del colapso 4.2. Disidencias y rebeliones internas 4.2.1. Insurgencia huthi en la gobernación de Saada (a) Las causas pendientes del zaydismo (b) Al Qaeda e Irán: la sombra de la duda (c) Desarrollo del conflicto 4.2.2. -

Annual-Report-2005 10.167 MB

5 Annual Report 2005 Social Fund for Development Faj Ettan, P.O. Box 15485 Sana’a Republic of Yemen Republic of Yemen [email protected] Social Fund for Development www.sfd-yemen.org Republic of Yemen | Social Fund for Development Annual Report 200 In the Name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful His Excellency Ali Abdullah Saleh President of the Republic of Yemen Imprint Social Fund for Development, Sana’a Annual Report 2005 Published by the Social Fund for Development, Sana’a Photos: Social Fund for Development staff, Christine Wawra, Volker Mantel All texts and pictures are subject to the copyright of the relevant institutions. © Social Fund for Development, Sana’a 2006 This document can be obtained from the Social Fund for Development Faj Ettan, P.O.Box 15485 Sana’a, Republic of Yemen Tel.: +967-1-449 668-9, 449 671-77 Fax: +967-1-449 670 Email: [email protected] Website: www.sfd-yemen.org Graphic design and layout: MEDIA DESIGN, Volker Mantel, [email protected] 4 | Social Fund for Development - Annual Report 2005 Contents The Social Fund for Development - At a Glance 6 Board of Directors 7 Statement of the Chairman of the Board of Directors 8 Statement of the Managing Director 9 Executive Summary 10 The Institutional Impact of the Social Fund for Development 12 2005 Operations 16 Targeting and allocation of funds 16 Education 18 Cultural Heritage and Rural Roads 24 Water and Environment 28 Health and Social Protection 31 Training and Organizational Support 39 Small and Micro-Enterprise Development 44 SFD’s Institutional Management 48 Monitoring and Evaluation 51 Funding Situation 53 Annexes 58 References 68 5 The Social Fund for Development At a Glance Yemen’s government established the Social Fund for Development (SFD) in 1997 to help in mitigating the ef- fects of economic reforms, fighting poverty and implementing the government’s social and economic plans. -

Yemen Events Log 3

Yemen Events Log 3 This is a publicly available events log to keep track of the latest coalition airstrikes on civilians or civilian infrastructure in Yemen, plus any other significant reports or events that are related. It is being updated daily a couple of dedicated independent activists who have a concern for the people of Yemen and a desire to see the end of this unfolding catastrophe. If you would like to help, please drop me a direct message on Twitter. @jamilahanan For current data, May 2018 onwards, see here: May 2017 - April 2018 https://docs.zoho.com/file/1g2al5ce282ae1ccc4ea7ac011b61edb74b21 This log contains events from November 2016 - April 2017. Previous events can be found here: August 2016 - October 2016 https://docs.zoho.com/file/qqptj5d51d260604b48f691fb33fba2641be6 Before August 2016 https://docs.zoho.com/file/qu3o1a39ece47dff44380a9a48fdc45489ddf April 2017 30th April Legalcenter for Rights and Developement - Airstrikes April 30th 2017 https://www.facebook.com/lcrdye/photos/a.551858951631141.1073741828.551288185021551/8 18304141653286/?type=3&theater 29th April What are the reasons for the US-Saudi aggression on #Yemen, which have became known to all countries of the #world? https://twitter.com/PrincessOfYmn/status/858258474173706240 Yemen – the New Graveyard Where Empires Come to Die https://twitter.com/ShakdamC/status/858209772050558976 Legalcenter for Rights and Developement - Airstrikes April 29th 2017 https://www.facebook.com/lcrdye/photos/a.551858951631141.1073741828.551288185021551/8 17825941701106/?type=3&theater 28th April Legalcenter for Rights and Developement - Airstrikes April 28th 2017 https://www.facebook.com/lcrdye/photos/a.551858951631141.1073741828.551288185021551/8 17307905086243/?type=3&theater Sen. Rand Paul: The U.S. -

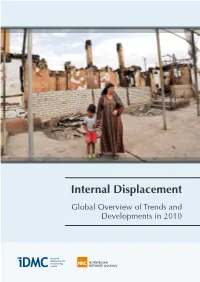

Internal Displacement Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2010 Internally Displaced People Worldwide December 2010

Internal Displacement Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2010 Internally displaced people worldwide December 2010 Turkey FYR Macedonia 954,000– Russian Federation Armenia Azerbaijan Uzbekistan Turkmenistan 650 1,201,000 6,500–78,000 At least 8,000 Up to About 3,400 Undetermined 593,000 Serbia Kyrgyzstan About About 75,000 225,000 Georgia Kosovo Up to Afghanistan 18,300 258,000 At least 352,000 Croatia 2,300 Bosnia and Herzegovina 113,400 Cyprus Pakistan Up to 208,000 At least 980,000 Israel Nepal Undetermined About 50,000 Occupied Palestinian Territory At least 160,000 India At least 650,000 Algeria Undetermined Chad Bangladesh 171,000 Undetermined Iraq Senegal 2,800,000 Laos 10,000–40,000 Undetermined Mexico Syria Sri Lanka About 120,000 Liberia At least At least Undetermined 327,000 The Philippines 433,000 At least 15,000 Côte d´Ivoire Lebanon Undetermined At least 76,000 Guatemala Togo Yemen Myanmar Undetermined Undetermined About 250,000 At least 446,000 Eritrea Indonesia Niger About 10,000 About 200,000 Timor-Leste Colombia Undetermined Undetermined 3,600,000–5,200,000 Ethiopia Nigeria About Undetermined CAR 300,000 192,000 Peru Sudan Somalia About 150,000 4,500,000– Republic of About 1,500,000 5,200,000 the Congo Kenya Up to 7,800 About 250,000 DRC Uganda About At least 166,000 1,700,000 Rwanda Undetermined Angola Burundi Undetermined Up to 100,000 Zimbabwe 570,000–1,000,000 Internal Displacement Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2010 March 2011 Children at the displace- ment camp of Karehe. -

Smoke Free Homes Introduction

Smoke Free Homes Introduction Every year, millions of people around the world die and millions more become ill as a result of smoking tobacco. Although many people in Bangladesh understand that smoking is harmful for themselves, the dangers of tobacco smoke for non smokers is less well understood. Smoke that comes from tobacco products used by others is called second hand smoke (SHS) and it is very harmful for unborn children, new-born babies, young children, adults and elderly people. Second hand smoke contains 7000 chemicals, many of which are hazardous to health. Most of the hazardous gases in SHS are invisible and if smoking takes place in a room, these can stay in the air for several hours even after the cigarette or bidi has been extinguished. Smoking is a form of addiction and many smokers find it extremely difficult to give up, even when they would like to. Therefore, as well as encouraging smokers to quit, it is very important to show them how they can protect children and non-smokers from second hand smoke. One way of doing this is to make homes “Smoke free”. In a smoke free home, adults make a voluntary promise not to allow anyone smoking inside their home and in front of children. The aim is to protect all the family members and in particular the children from the harmful effects of second hand smoke. All over the world, Imams and religious teachers have always supported health improvement within their communities. They are respected individuals and hold unique positions in the communities. -

The Impact of the Fragile Health System on the Implementation of Health Policies in Yemen

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.25.20200741; this version posted September 25, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 International license . The impact of the fragile health system on the implementation of health policies in Yemen Taha Hussein 1, Fekri Dureab2,3 , Raof Al-Waziza3, Hanan Noman 2, Lisa Hennig2 , Albrecht Jahn2 1- MSF-France, Aden, Yemen 2- Heidelberg Institute of Global Health, University Hospital Heidelberg, Germany 3- IRIA, Akkon Hochschule für Humanwissenschaften, Berlin, Germany Abstract Background: The on-going humanitarian crisis in Yemen is one of the worst in the world, with more than14 million people in acute need. The conflict in Yemen deteriorated the country’s already fragile health system and lead to the collapse of more than half of the health facilities. Health system fragmentation is also a problem in Yemen, which is complicated by the existence of two health ministries with different strategies. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of health system fragmentation on the implementation of health policies in Yemen across the global agendas of Universal Health Coverage (UHC), Health Security (GHS) and Health Promotion (HP) in the context of WHO’s priorities achieving universal health coverage, addressing health emergencies and promoting healthier populations. Methods: The study is qualitative research using key informant in-depth interviews and documents analysis. Results: There are many health stakeholders in Yemen, including the public, private, and NGO sectors - each with different priorities and interests, which did not always align with national policies and strategies.