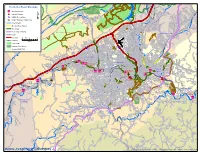

Chapter 2 – Roanoke River Basin Overview 8 Figure A-4 General Map of the Entire Roanoke River Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology and Mineral Deposits of the James River-Roanoke River Manganese District Virginia

Geology and Mineral Deposits of the James River-Roanoke River Manganese District Virginia GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1008 Geology and Mineral ·Deposits oftheJatnes River-Roanoke River Manganese District Virginia By GILBERT H. ESPENSHADE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1008 A description of the geology anq mineral deposits, particularly manganese, of the James River-Roanoke River district UNITED STAT.ES GOVERNMENT, PRINTING. OFFICE• WASHINGTON : 1954 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS· Page Abstract---------------------------------------------------------- 1 Introduction______________________________________________________ 4 Location, accessibility, and culture_______________________________ 4 Topography, climate, and vegetation _______________ .,.. _______ ---___ 6 Field work and acknowledgments________________________________ 6 Previouswork_________________________________________________ 8 GeneralgeologY--------------------------------------------------- 9 Principal features ____________________________ -- __________ ---___ 9 Metamorphic rocks____________________________________________ 11 Generalstatement_________________________________________ 11 Lynchburg gneiss and associated igneous rocks________________ 12 Evington groUP------------------------------------------- 14 Candler formation_____________________________________ 14 Archer Creek formation________________________________ -

Docket # 2018-318-E - Page 11 of 97

EXHIBIT DJW - 5.0 ELECTRONICALLY Page 1 of 18 Date: May 14, 2015 Document: EXHIBIT 2 – AMENDED STIPULATIONS – PLEA AGREEMENT Cases: US DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA WESTERN DIVISION NUMBERS 5:15-CR-67-H-2 AND 5:15-CR-68- H-2 FILED Findings: - 2019 1. Dan River Steam Station (pages 43 - 48) – The Court found Defendants guilty and Defendants plead guilty to four counts (sets of violations) at Dan River. March a. Count One is that the company violated the Clean Water Act for the unpermitted discharge through the 48-inch stormwater so and the Defendant aided and abetted another 4 in doing so. Furthermore, the Court found that the Defendant acted negligently in doing 4:55 so. b. Count Two is that Defendant violated the CWA by not maintaining the 48-inch storm PM water pipe which constituted a violation of its NPDES permit which requires that the - permittee to properly maintain its equipment. Furthermore, the Court found that the SCPSC Defendant acted negligently in doing so and that the Defendant aided and abetted another in doing so. c. Count Three is that Defendant violated the CWA for the unpermitted discharge through - the 36-inch stormwater pipe at Dan River of coal ash and coal ash wastewater from a Docket point source into a water of the US. Furthermore, the Court found that the Defendant acted negligently in doing so and that the Defendant aided and abetted another in doing # so. 2018-318-E d. Count Four is that Defendant violated the CWA by not maintaining the 36-inch storm water pipe which constituted a violation of its NPDES permit which requires that the permittee to properly maintain its equipment. -

Benthic TMDL Development for the Roanoke River, Virginia

Benthic TMDL Development for the Roanoke River, Virginia Submitted to Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Prepared by 2300 N Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 March 2006 Benthic TMDL Development for Roanoke River Executive Summary Introduction As required by Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act and current EPA regulations, states are required to develop Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) for waterbodies that exceed water quality standards. The Roanoke River was included on Virginia’s 1996 Section 303(d) TMDL Priority List and Report (DEQ, 1996) because of violations of the General Standard (benthic impairment). The headwaters of the Roanoke River originate in southwest Virginia. The Roanoke River flows through southcentral Virginia before crossing the North Carolina state line and discharging into the Albemarle Sound in North Carolina. Impairment Listing The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) uses biological monitoring of benthic macroinvertebrates as one method to assess support of the aquatic life use for a waterbody. Bioassessments of the benthic macroinvertebrate community of the Roanoke River were performed by DEQ using modified Rapid Bioassessment Protocols (EPA, 1999). Results of bioassessments indicated a moderately impaired benthic community at three monitoring stations on the river (4AROA202.20, 4AROA206.03, and 4AROA206.95). Therefore, since the river only partially supports the designated aquatic life use, the General Standard is being violated. As a result, the Roanoke River was included on the Section 303(d) list. Although biological assessments indicated the creek is impaired, additional analyses described in this report were required to identify the causal pollutant (stressor) and sources within the watershed. -

Bacteria Tmdls for Wilson Creek, Ore Branch and Roanoke River Watersheds, Virginia

Bacteria TMDLs for Wilson Creek, Ore Branch and Roanoke River Watersheds, Virginia Submitted by Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Prepared by and 2300 N Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 February 2006 Bacteria TMDLs for Wilson Creek, Ore Branch and Roanoke River Watersheds Executive Summary This report presents the development of Bacteria TMDLs for the Wilson Creek, Ore Branch and Roanoke River watersheds, located in the Upper Roanoke River Basin. Segments of Wilson Creek, Ore Branch and the Roanoke River were listed as impaired on Virginia’s 1998 303(d) Total Maximum Daily Load Priority List and Report (DEQ, 1998) because of violations of the state’s water quality standard for fecal coliform bacteria. These segments were also included on Virginia’s 2002 303(d) Report on Impaired Waters and 2004 305(b)/303(d) Water Quality Assessment Integrated Report. The impaired segments are located in the Upper Roanoke River Basin in southwestern Virginia. Description of the Study Area Wilson Creek is a tributary to the North Fork Roanoke River and is located in Montgomery County, while Ore Branch is a tributary to the Roanoke River and flows from Roanoke County into Roanoke City. The impaired segment of the Roanoke River begins in Salem City and flows through Roanoke City into Roanoke County. All three streams are located in the Upper Roanoke River Basin (USGS Cataloging Unit 03010101). The watershed is approximately 371,658 acres (580 square miles) and drains portions of Floyd, Montgomery, Roanoke, Botetourt, Bedford and Franklin Counties and all of Salem and Roanoke Cities. Bacteria TMDLs have already been approved for five impaired streams in the watershed: Carvin Creek, Glade Creek, Laymantown Creek, Lick Run and Tinker Creek. -

Link to Duke Joint Factual Statement

UNITED STAT8S DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA WESTERN DIVISION No . 5 : 15-CR-62-H No. 5 : 15-CR-67-H No. 5 : 15-CR-68-H UNITED STATES OF AMSRICA v. JOINT FACTUAL STATEMENT DUKE ENERGY BUSINESS SERVICES LLC DUKE ENERGY CAROLINAS , LLC DUKE ENERGY PROGRESS , INC . I . INTRODUCTION Defendants Duke Energy Business Services LLC (" DUKE ENERGY BUSINESS SERVICES"), Duke Energy Carol inas, LLC (" DUKE ENERGY CAROLINAS") , and Duke Energy Progress, Inc. ("DUKE ENERGY PROGRESS") , (collectively referred to as " Defendants") and the United States of America, by and through t he United States Attorneys for the Eastern District of North Carolina, the Middle Distri ct of North Carolina and the Western District of North Carolina and the Environmental Crimes Section of the United States Department of Justice (collectively referred to herein as " the United States" or "the government" ) , hereby agree that this Joint Factual Statement is a true and accurate statement of the Defendants ' crimi nal conduct a nd that it provides a sufficient basis for the Defendants ' pleas of guilty to the following charging documents and the terms of the Plea Agreements : United States v. Duke Energy Business Services, LLC , and Duke Energy Progress, Inc ., No. 5 : 15-CR-62-H; United States v . Duke Energy Business Services, LLC , Duke Energy Carolinas, LLC , and Duke Energy Progress, Inc., No . 5 : 15-CR-67-Il; and United States v . Duke Energy Business Services, LLC , Duke Energy Carolinas, LLC , and Duke Energy Progress, Inc. , No . 5 : 15-CR-68-H . The charges from the Middle District of North Carolina and the Wes tern District of North Carolina have been transferred to the Eastern District of North Carolina for purposes o f plea pursuant to Fed. -

Blue-Ridge-Parkway-Map.Pdf

20 To Richmond 340 29 250 0 1 5 Km 10 Loft Mountain Information Center 33 CHARLOTTESVILLE 0 1 5 Miles 10 h HARRISONBURG a o d n r a e n v i e R North h S Shenandoah 250 276 National Park S (Entrance Fee) D k u y d l l 11 i e n 64 y e M 20 D t r n 256 S i o ve u Milepost along t h 20 98 Blue Ridge Parkway R iv er 340 Overlook 81 s Ch n rist i ia 29 a n t Tunnel under 13 feet s n u (located near southern o end of parkway) Rockfish Gap M C r 1900ft No direct access e 254 n e a 6 to parkway k 3 F 3 Northern End of Food service WAYNESBORO Blue Ridge Parkway 3 275 11 Picnic area 6 er 250 624 iv R 42 64 631 151 STAUNTON Lodging 15 sh fi 6 ck 250 Ro Humpback Rocks Campground 664 Visitor Center 81 340 Greenstone Trail 42 10 Wintergreen 254 Ravens Roost 11 Humpback 13 Mtn 252 664 n Sherando Lake t M 814 Woods 56 y Mountain a l d To Richmond 151 n i G L 701 F I Bald 20 R T J T Mountain am E L e A E Twenty s 24 T N Minute O Cliff R i R Crabtree v T e The r H Falls T N ye Priest O M R Tye River i R v O 56 er T Gap U 56 H N T 5 A Whetstone Ridge I N Steeles 30 29 60 M Tavern O 42 151 Wigwam U 11 The Friar Falls N 26 T Yankee Horse Ridge A The Cardinal S 81 o I u N t Irish Gap h GEORGE R i 252 v Amherst e 40 r WASHINGTON NATIONAL 23 Whites Gap T 39 Overlook FOREST 60 o b 2567ft a c 29 42 c 39 o BUENA Indian Gap R Forge 5 o Monroe VISTA w To Petersburg Mountain M 50 o er u iv n R t 460 39 ury 60 a 60 Ma in 6 130 64 20 Little R r House LEXINGTON Otter Creek James ive Mountain 10 Bluff 42 Mtn 60 Big House 501 Lowest Elevation 501 Mountain on Parkway 649ft -

Conserving the Roanoke River

Conserving the Roanoke River Conservation Action Plan November 2005 Preface The Lower Roanoke River Project (LRRP) Conservation Plan consists of five elelments. The first of these elements is this summary report containing the key components of a written conservation action plan. The second is a Conservation Action Planning Workbook (developed by TNC using a Microsoft Excel platform) in which information about stresses, threats, strategies, and strategic success is routinely updated with conservation partners. The third is a GIS-based database including land-ownership maps and many kinds of spatial data for illustrating and evaluating various conservation scenarios. The fourth is a set of models (public policy, flow, flood, and ecological response) that allow us to evaluate the way different strategies for management of the system’s hydrology produce ecological effects. The fifth is a site protection plan consisting of priority tract maps and a spreadsheet for tracking conservation progress on each of them, as well as all of them cumulatively. In developing and revising the Conservation Plan for the Lower Roanoke over the past several years, The Nature Conservancy has utilized a series of workshops to address conservation strategies at the site scale. The goal of these workshops was to apply The Nature Conservancy’s site conservation “5-S Framework” to the Roanoke River project area, thereby developing a conservation blueprint for action and a baseline from which to measure its success over time. Primary partners in the planning process have included the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the NC Wildlife Resources Commission (WRC), among others. During calendar year 2005, the TNC-NC Conservation staff revised the Roanoke plan through another series of workshops in collaboration with the Southeast Aquatic Resource Partnership (SARP). -

Roanoke River Blueway Access Points

h F !F ! KINZIE 4TH OAK Roanoke River BluewayMILLER RAMP HUMBERT CRAIGVALLEY WALNUT POPLAR GILLIE FIELDS KEFFER CATAWBA CREEK OLDE RT 604 SKY OLD TRAM MOUNTAIN !F MAPLE !| Blueway Access !F OAKWOOD BLUE RIDGE OAK COALING PARKVIEW BUGLE INTERSTATESIMMONS 81 FLINT SPRING HOLLOW ` 648 DOVE _ Æ SCALYBARK Hazard/Portage GIBSON RIDGE DEREK APACHE ÿ CASEY WATES CALDER RIDGE CARVINS COVE DOGAN LULA SUMMIT h TIMER PINE USGS Stream Gage RESERVOIR LAKEVIEW STONEBRIDGE MOUNTAIN PASS BRADSHAW BRYANT JENSEN N & W 2ND LACEY KIDDER LONGWOOD ¹ ALLTREE CATAWBA VALLEY!F WINDFALL !F VDGIF Birding & Wildlife Site UPDIKE MORNING DOVE INTERSTATE 81 HUNTERS FOXCROFT BLUEBIRD CLOVERDALE LEE COUGAR LAYMANTOWN BENDING OAK CHASE KEATON ANGEL DAN LAKERIDGE C FACULTY VISTA River/Stream MOORE AUTUMN GANDER a COOK DEER FAIRFIELD LOMAN r ENON v INDUSTRIAL COLONIAL in BRITISH WOODS I81 TOAD CLOVERDALE Carvins Cove BELLE HAVEN s RICHARDSON Stocked Trout Waters !F LILA MCINTOSH C HOPE FILLY APPLE Natural Reserve LABAN r STAYMAN e WILLIAMSON SHADWELL ARCHWAY SOFT e YORK TIMBERVIEW CALVERT HITECH k CAROLINA POST OAK GreenwayARABIAN BARRENS INDIAN TERESA KNOLLWOOD ALPINE PARK HUNTERS WEBSTER NEWPORT OLSEN WILLIAMSONDEXTER HUGH ROYCE Blue Ridge Parkway Loch Haven WEST Havens Wildlife Management Area JANEE VIVIAN EAST SERENITY BOXLEY HOLLINS WOOD HAVEN Botetourt County CRESTLAND QUAIL DOE RAY Road I81 BUCK MANOR SANDYRIDGE DUTCH OVEN HEDGELAWN OAKLANDELDEN THIRLANE OLD MOUNTAIN NELL DENT ROME LOCH HAVEN SHORE AIRPORT TINY CAPITO FLORIST SIERRA Interstate 00.5 1 2 RAM DAVIS BLACKSBURG -

8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina

8 Tribes, 1 State: North Carolina’s Native Peoples As of 2014, North Carolina has 8 state and federally recognized Native American tribes. In this lesson, students will study various Native American tribes through a variety of activities, from a PowerPoint led discussion, to a study of Native American art. The lesson culminates with students putting on a Native American Art Show about the 8 recognized tribes. Grade 8 Materials “8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina” PowerPoint, available here: o http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2014/06/NCNativeAmericans1.pdf o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode”; upon completion of presentation, hit ESC on your keyboard to exit the file o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to [email protected] “Native American Art Handouts #1 – 7”, attached North Carolina Native American Tribe handouts, attached o Lumbee o Eastern Band of Cherokee o Coharie o Haliwa-‑ Saponi o Meherrin o Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation o Sappony o Waccamaw Siouan “Create a Native American Art Exhibition” handout, attached “Native Americans in North Carolina Fact Sheet”, attached Brown paper or brown shopping bags (for the culminating project) Graph paper (for the culminating project) Art supplies (markers, colored pencils, crayons, etc. Essential Questions: What was life like for Native Americans before the arrival of Europeans? What happened to most Native American tribes after European arrival? What hardships have Native Americans faced throughout their history? How many state and federally recognized tribes are in North Carolina today? Duration 90 – 120 minutes Teacher Preparation A note about terminology: For this lesson, the descriptions Native American and American Indian are 1 used interchangeably when referring to more than one specific tribe. -

Early Settlers: Their Laws, Morals, Etc

CHAPTER I Country west of the Blue Ridge, and the first settlers of Southwest Virginia – Their trouble with the Indians – Frontier warfare – Gradual formation of the various counties until 1861 – Primitive life of the early settlers: their laws, morals, etc. SOUTHWEST VIRGINIA AND SHENANDOAH VALLEY The Blue Ridge Mountains, as a landmark, have played an important part in Virginia’s history. Long before the fertile valleys and mineral hills west of these mountains were discovered, or the gaze of the white man rested upon New River, the eastern portion of the State had some 80,000 people, and Shenandoah Valley three or four hundred souls. The forefathers of the latter came into this valley by way of Harper’s Ferry from Pennsylvania, of whom we shall have more to say in the second part of this work. The threading of the labyrinth of Rosamond’s bower could scarcely have been more difficult than the tracing of the footsteps of these earlier settlers, in any chronological order, who first came into that country now known as Southwest Virginia. The want of all records, which the early settlers failed to preserve, reduces the chronicler of events to groping in the dark, and learning from uncertain sounds the paths trod by our forefathers. Several reasons may be assigned for this unfortunate state of affairs. The primitive, struggling life of those earlier pioneers was not conducive to the recordation of events, and the constant destruction of their settlements by the Indians was often a clean sweep, where the inhabitants could not even escape with their lives, to say nothing of records, if any were preserved. -

02067820 TALBOTT and TOWNES RESERVOIRS These Two Reservoirs on the Dan River Are Operated As a Unit for Storage of Water for Pinnacles Hydroelectric Plant

SOUTH ATLANTIC SLOPE BASIN 692 LAKES AND RESERVOIRS IN SOUTH ATLANTIC SLOPE BASIN 02067800; 02067820 TALBOTT AND TOWNES RESERVOIRS These two reservoirs on the Dan River are operated as a unit for storage of water for Pinnacles hydroelectric plant. TALBOTT DAM LOCATION.--Lat 36°40'36", long 80°23'51", Patrick County, Va, Hydrologic Unit 03010103, 4.5 mi northeast of Kibler. DRAINAGE AREA.--20.2 mi2. TOWNES DAM LOCATION.--Lat 36°41'11", long 80°25'49", Patrick County, Va, Hydrologic Unit 03010103, 4 mi north of Kibler. DRAINAGE AREA.--32.9 mi2. PERIOD OF RECORD.--February 1939 to December 1945 and January 1948 to September 1960 (combined monthend contents only pub- lished in WSP 1723), October 1960 to current year. REMARKS.--Total capacity of Talbott Reservoir is 350,000,000 ft3 and Townes Reservoir is 60,000,000 ft3. Filling was started in Talbott Reservoir Feb. 13, 1939, and in Townes Reservoir several months earlier. Records furnished by city of Danville, Virginia. (See station 02068500.) 02077280 HYCO LAKE LOCATION.--Lat 36°30'28", long 79°02'48", Person County, Hydrologic Unit 03010104, at outlet control structure 0.4 mi northwest of dam on Hyco River, 1.1 mi southwest of McGehees Mill, and 8 mi northwest of Roxboro. DRAINAGE AREA.--189 mi2. PERIOD OF RECORD.--October 1964 to current year. Prior to October 1970, published as "Roxboro Steam-Electric Generating Plant Lake." GAGE.--Water-stage recorder and tape gage. Prior to Feb. 11, 1965, staff gage at upstream end of outlet control structure. Datum of gage is 399.79 ft above sea level (levels by Carolina Power and Light Co.). -

City of Roanoke PCB TMDL Action Plan

Submitted to: The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Blue Ridge Regional DEQ Office MS4 Stormwater Permitting Div. 3019 Peters Creek Road Roanoke, VA 24019 CITY OF ROANOKE Effective July 1, 2016 PCB TMDL ACTION PLAN Stormwater Utility Public Works Service Center 1802 Courtland Road, NE Roanoke, VA 24012 City of Roanoke PCB TMDL Action Plan City of Roanoke POLYCHLORINATED BIPHENYLS (PCB) TMDL ACTION PLAN INTRODUCTION In December 2009, a PCB TMDL was established for the Roanoke River. Within the City of Roanoke, the Roanoke River and three of its tributaries, Masons Creek, Peters Creek and Tinker Creek were found to be contaminated for polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs); thus failing to meet their designated uses under Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act and the Virginia Water Quality Monitoring, Information and Restoration Act. Water quality standards designate a waterbody’s uses. In Virginia, the designated uses for surface water bodies are: aquatic life, fish consumption, public water supplies (where applicable), recreation (swimming), shell fishing, and wildlife. If a water body is too polluted to meet its designated uses, it is listed as an impaired stream on the 303(d) list. A TMDL study is then conducted to create a pollution limit. A TMDL or total maximum daily load is established to define the limit of a pollutant that a water body can receive and process while still maintaining health for its designated uses. Due to the fact that PCBs bioaccummulate in fish tissue, the TMDL endpoints were developed to protect fish for human consumption and are more stringent than 1700pg/L which is what the state requires for human health (Tetra Tech, 2009).