The Rest of STILL LIFE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Music :A Comprehensive Ilbrar

1wmm H?mi BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT or Hetirg W, Sage 1891 A36:66^a, ' ?>/m7^7 9306 Cornell University Library ML 100.M39 V.9 The art of music :a comprehensive ilbrar 3 1924 022 385 342 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022385342 THE ART OF MUSIC The Art of Music A Comprehensive Library of Information for Music Lovers and Musicians Editor-in-Chief DANIEL GREGORY MASON Columbia UniveTsity Associate Editors EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin Managing Editor CESAR SAERCHINGER Modem Music Society of New Yoric In Fourteen Volumes Profusely Illustrated NEW YORK THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC Lillian Nordica as Briinnhilde After a pholo from life THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME NINE The Opera Department Editor: CESAR SAERCHINGER Secretary Modern Music Society of New York Author, 'The Opera Since Wagner,' etc. Introduction by ALFRED HERTZ Conductor San Francisco Symphony Orchestra Formerly Conductor Metropolitan Opera House, New York NEW YORK THE NASTIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC i\.3(ft(fliji Copyright, 1918. by THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc. [All Bights Reserved] THE OPERA INTRODUCTION The opera is a problem—a problem to the composer • and to the audience. The composer's problem has been in the course of solution for over three centuries and the problem of the audience is fresh with every per- formance. -

Catálogo 2020 Haras San Pablo

CATÁLOGO 2020 HARAS SAN PABLO 1 PERÚ En la Carátula y en esta página: TOFFEE, alazana nacida el 16 de Julio del 2016, hija de WESTOW (USA) y LICHA LICHA (USA), por MR. GREELEY (USA). Defendiendo los colores del Stud Black Label y entrenada por Juan Suárez Villarroel, ganó el Clásico Enrique Ayulo Pardo (G1) (foto carátula), Roberto Álvarez Calderón (L), Iniciación (R), Selectos - Potrancas (R) y Ala Moana (foto arriba). POTRANCA CAMPEONA DE 2 AÑOS y POTRANCA CAMPEONA DE 3 AÑOS el 2019 HARAS SAN PABLO (Fundado en 1979) PRODUCTOS FINA SANGRE DE CARRERA NACIDOS EN EL SEGUNDO SEMESTRE DE 2018 HIJOS DE: FLANDERS FIELDS (USA) KOKO MAMBO (PER-G1) MAN OF IRON (USA) MINISTER’S JOY (USA) YAZAMAAN (GB) Irrigación Santa Rosa Sayán - Lima, Perú 2020 INDICE Instrucciones para el uso de este catálogo ..................................................................................7 Plantel de Reproductores del Haras San Pablo - Padrillos y Yeguas Madres .....................12 Caballos CAMPEONES criados en el Haras San Pablo ..........................................................16 Clásicos GRUPO UNO, GRUPO DOS, GRUPO TRES ganados por el Haras San Pablo ..17 Productos ganadores de los Clásicos Selectos y Copa Criadores de la Asociación de Criadores de Caballos de Carrera del Perú ..............................................................................21 PADRILLOS EDITORIAL (USA), por War Front en Playa Maya por Arch ...............................................24 FLANDERS FIELDS (USA), por A.P. Indy en Flanders por Seeking the Gold .................28 KOKO MAMBO (PER), por Apprentice en Not For Sale por Mashhor Dancer ...............32 MAN OF IRON (USA), por Giant´s Causeway en Better Than Honour por Deputy Minister ...........36 MINISTER’S JOY (USA), por Deputy Minister en Meghan’s Joy por A.P. -

The Collegian Special Collections and Archives

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV The Collegian Special Collections and Archives 9-1-2008 The Collegian (2008-09-01) Isis Lopez The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/collegian Recommended Citation The Collegian (BLIBR-0075). UTRGV Digital Library, The University of Texas – Rio Grande Valley This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and Archives at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Collegian by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE STUDENT VOICE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT BROWNSVILLE AND TEXAS SOUTHMOST COLLEGE THE Volume 61 Monday OLLEGIANwww.collegian.utb.edu CIssue 3 September 1, 2008 STEADY AIM Campus’ tab for Dolly: $1M By David Boon is something that we planned to Staff Writer do. ... We didn’t need Dolly to tell us that, we knew we were going to Hurricane Dolly cost the do that. But Dolly kind of pushed university more than $1 million, us along a little bit.” officials say. The Education and Business This figure includes money that Complex’s cooling unit, known is being spent on preventative as a “chiller,” and the campus maintenance to avoid further windows, specifically in Tandy damage to the buildings should Hall, sustained major damage there ever be a similar event. during the hurricane, which struck “If you add up everything, the Rio Grande Valley on July 23. [it] would be over a million,” “A chiller is an air-conditioning said Alan Peakes, assistant vice unit which cools the water, which president of Facilities Services. -

Earth Founders Fund Talking with Shirley Meneice

Earth Founders Fund Talking with Shirley Meneice THE GARDEN CLUB OF AMERICA Winter 2016 12503 - GCA Winter 2016_Layout 1 11/18/15 11:17 AM Page 1 GCA Bulletin Winter 2016 The purpose of The Garden Club of America is to stimulate the knowledge and love of gardening, to share the advantages of association by means of educational meetings, conferences, correspondence Dig deeper... and publications, and to restore, be ENCHANTED. be DELIGHTED. be INSPIRED. improve, and protect the quality of BANK TO BEND WITH LADY CAROLYN ELWES the environment through educational Saturday, March 12, 2016 programs and action in the fields Join featured speaker Lady Carolyn Elwes of Colesbourne Park, England’s greatest snowdrop garden, for her lecture, of conservation and civic improvement. “Snowdrops at Colesbourne, Gloucestershire.” Enjoy an afternoon workshop on the bulbs of Winterthur’s renowned March Bank, a sale of rare and unusual snowdrops and other Submissions and Advertising plants, and tours of the Winterthur Garden. Lecture: $10 per Member. $20 per nonmember. Registration encouraged. The Bulletin welcomes letters, articles with photographs, story ideas, and original artwork from members of GCA clubs. WHAT’S IN BLOOM? Email: [email protected] for more information or visit the Spring is the perfect time to stroll Henry Francis du Pont’s Bulletin Committee page in the members area of the GCA masterful 60-acre garden and enjoy a succession of website: www.gcamerica.org for the submission form. showstopping blooms. Spring festivals celebrate the March Bank, Sundial Garden, Azalea Woods, and Peony Garden. Submission deadlines are February 15 (Spring), May 15 Narrated tram tours available. -

The Pork and Lamb You Can Always Count On. Kings

PapaCRANroRD CHRONICLE Thursday, May 14. Ml t Where eke but Kines? The Pork and Lamb you can always count on. When it comes to fresh meats, our butchers go out of their way to give you ideas, our specials include Ftlet Mignons and Whole or Split Chicken Breasts. SERVING CRANFORD, QARWOOD «nd KENILWORTH the very best. Tb round out your menus, our Fanner's Corner offers you Jersey Fresh That's why our Butcher's Corner offers you nothing less than Western Grain- vegetables from Asparagus to Swiss Chard as well as Strawberries and firefcof- Vol. 94 No. 20 Published Every Thursday Thursday, May 21,1987 Fed Boric and USDA Choice Lamb- ^nd those aren't bur only assurances of the-season Cherries fresh from California. USPS 136 800 Second Class Postage Paid Cranford, N.J. 30 CENTS quality, because our butchers always trim our PDrk and Lamb for the best value And along with the best of the Wursts, our Deli Corner specials include as well as the best flavor. In addition, they make it their pleasure to prepare any Freshly Prepared Salads including Cucumber A Dill and Tomato & Onions. cut to your specifications at no extra charge. So let all of our specials invite you to Kings this week. From our Pork and As for special values in Pork and Lamb, our selections go from Roasts, Chops Lamb to our Fruits and Vegetables, you'll find a corner on freshness throughout 'Cinderella' lands a soap and Cutlets to Spare Ribs, Tenderloins and Kabobs. And for more outdoor-dining the store. -

Concert: Choral Collage Derrick Fox

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-10-2015 Concert: Choral Collage Derrick Fox Janet Galván Ithaca College Chorus Ithaca College Madrigal Singers Ithaca College Women's Chorale See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Fox, Derrick; Galván, Janet; Ithaca College Chorus; Ithaca College Madrigal Singers; Ithaca College Women's Chorale; and Ithaca College Choir, "Concert: Choral Collage" (2015). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1240. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1240 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Authors Derrick Fox, Janet Galván, Ithaca College Chorus, Ithaca College Madrigal Singers, Ithaca College Women's Chorale, and Ithaca College Choir This program is available at Digital Commons @ IC: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1240 Choral Collage Ithaca College Chorus Derrick Fox, conductor Ithaca College Madrigal Singers Derrick Fox, conductor Ithaca College Women's Chorale Janet Galván, conductor Ithaca College Choir Janet Galván, conductor Ford Hall Saturday, October 10th, 2015 7:30 pm Program Ithaca College Chorus Derrick Fox, conductor Adam Good, graduate assistant Jon Vogtle and Alexander Greenberg, collaborative pianists This Beautiful Earth "Celebration" Ke Nale Monna Sotho Folk Songs "Remembrance" Requiem a tre voci Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) Erik Kibelsbeck*, organ David Quiggle*, viola "The Earth" The Ground Ola Gjeilo from Sunrise Mass (b. 1978) Lindsay Gilmour*, choreography "The Heavens" Tonight Eternity Alone Rene Clausen (b. -

Profile: Take Flight

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well Profile Campus News, Newsletters, and Events Fall 2005 Profile: akT e Flight University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/profile Recommended Citation University Relations, "Profile: akT e Flight" (2005). Profile. 25. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/profile/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Campus News, Newsletters, and Events at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Profile yb an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OE MINNESOTA MORRIS - Voluine~X!;Edition 1, Fall 2005 llll~l~lffiliim~11i~~m111111 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MORRIS 3 1956 00474 8246 In this issue ... Chancellor's message .. .. ... .... ............... ... ..... .... .. .... ... ... ... ... ... .... ..... .. ...................... .. ...... .. ... .. .. ....... .. ... ... ... .... ..... ....... ..... 1 Associate vice chancellor for external relations greeting .. .. ... .. ........... ... .. ..... ....... ... ... ....... ... ... ... ... ......... ..... .. .. .. ............. 2 Honor Roll stories Meyer scholarship gift honors parents, grandchildren and WCSA .. ... ...... ..... ... .. .... .. .. .. .. ... 3 Barbara McGinnis: "Big on scholarships " .................... ... .. ........ .. ... .. .. ............. ................ .4 Nathaniel E. Williams Memorial -

![Legends of Saint Joseph, Patron of the Universal Church [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4501/legends-of-saint-joseph-patron-of-the-universal-church-microform-1114501.webp)

Legends of Saint Joseph, Patron of the Universal Church [Microform]

/ / *C^ #? ^ ////, A/ i/.A IMAGE EVALUATION TEST TARGET (MT-3) 1.0 IB %. ^ !E U£ 112.0 I.I 1.8 1.25 U 11.6 # \ SV \\ V ^^J'V^ % O^ o> Photographic €^ 23 WEST MAIN STREET WEBSTER, N.Y. 14580 Sciences (716) 872-4503 Corporation ^*... "•"^te- «iS5*SSEi^g^!^5«i; 'it^, '<^ t& CIHM/ICMH CIHM/ICMH Microfiche Collection de Series. microfiches. Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions / Institut Canadian de microreproductions historiques S ^ <; jv. - s»«5as^a«fe*Sia8B®I6jse»a!^«i)^w«*«i*asis»swp£>9^^ '*s* - ' 1 _ ssfijr Technical and Bibliographic Notes/Notes techniques et bibliographiques microfilm^ le meilleur exemplaire The Institute has attempted to obtain the best L'Institut a se procurer. Les d6tails original copy available for filming. Features of this qu'il lui a 6t6 possible de uniques du copy which may be bibliographically unique, de cet exemplaire qui sont peut-Atre bibliographique, qui peuvent modifier which may alter any of the images in the point de vue peuvent exiger unc reproduction, or which may significantly change une image reproduite, ou qui normale de filmage the usual method of filming, are checked below. modification dans la m6thode sont indiqu^s ci-dessous. Coloured covers/ Coloured pages/ D Couverture de couleur Pages de couleur Covers damaged/ Pages damaged/ D Couverture endommag^e Pages endommagdes Covers restored and/or laminated/ Pages restored and/or laminated/ D Couverture restaur6e et/ou pellicul6e Pages restaur6es et/ou pellicul6es stained or foxed/ Cover title missing/ Pages discoloured, tachetdes ou piqu6es Le titre de couverture manque Pages d6color6es, Coloured maps/ Pages detached/ D Cartes g6ographiques en couleur Pages ddtach^es Coloured ink (i.e. -

THOROUGHBRE'ntm -L D®A®I®L®Y N•E^W^S ^ WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 1998 $2 Daily

the Thoroughbred Daily News is delivered to your fax each morning by 5 a.m. For subscription information, please call (732) 747-8060. THOROUGHBRE'nTM -L D®A®I®L®Y N•E^W^S ^ WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 1998 $2 Daily N • E • w • S K*e*e*n*e*l*a*n*D TODAY RESULTS STUD FEE SET FOR SKIP AWAY Rick Trontz's SUN BLUSH TOPS KEENELAND TUESDAY Selling Hopewell Farm in Lexington, Kentucky has set the 1999 as hip number 3295, the nine-year-old mare Sun Blush stud fee for Horse of the Year candidate Skip Away (Ogygian-lmmense, by Roberto), in foal to Boone's Mill (Skip Trial) at $50,000 live foal. "We think it's a great (Carson City), brought $290,000 to top yesterday's value for a horse like Skip Away," said Trontz. "We've session of the Keeneland November Breeding Stock had an excellent response from breeders and look for Sale. Phil T. Owens, agent, bought the half-sister to ward to an outstanding book of mares." The Champion multiple graded stakes-winner Mariah's Storm (Rahy) Three-Year-Old Colt of 1996 and Champion Older Horse from the consignment of John Williams, agent. Sun of 1997, Skip Away retired with 18 wins and earnings Blush is the dam of the stakes winning three-year-old of $9,616,360. filly Relinquish (Rahy). Hip number 3394, a bay colt by Supremo~By Four Thirty (Proudest Roman), was bought CARTIER AWARDS ANNOUNCED The Cartier for $73,000 by John Oxiey to bring the top weanling Awards, the first in a number of competing awards price of the session. -

July 10533873.Pdf

J ULY ED ITED BY OS CAR FAY ADA M S H IG H midsumm er has come m ds mm er m ute , i u h Of son r c to sce ntand si t. g , but i h g Th e sun 15 h l h m h eaven th e ski es are r g , b ight And full to blessednws. M R R Lxm s O IS. Tlze Ode a/L zfir. BOSTON D L O T H R P A N D M P A N Y . O C O F RA N KLI N AN D H AW LEY STR E ETS om m e nt 1 886 BY C , , R P AN D O P . D . LOT H O C M A N Y CO M POS I T ION A N D E LE CTROTYPI NG BY ' l . M T T N A D M P N Y . C. A OO N CO A P RE FAC E . OF the summer months July has always been the r r r of one most favo ed of the poets , who have neve ti ed It i s fioodtide singing the praises of midsummer. the of r. Th e fr s of r m m r the yea eshnes ea ly su e has passed , it is true but what June promised July fulfils . Not yet has com e the chill at eventide that in late summer hints o r faintly, but n ne the less su ely, of autumn and the Th e rook are not r i e r fading leaf . -

Dragon Magazine #136

Issue #136 Vol. XIII, No. 3 August 1988 SPECIAL ATTRACTION Publisher Mike Cook 7 Urban Adventures: An orc in a dungeon is a foe. An orc in the city could be mayor. Editor 8 Building Blocks, City Style Thomas Kane Roger E. Moore Is there a fishmonger in this town? This city-builder has the answer. Assistant editor Fiction editor 18 The Long Arm of the Law Dan Howard Robin Jenkins Patrick L. Price Crime and punishment in FRPG cities; or, flogging isnt so bad. 22 Taking Care of Business Anthony D. Gleckler Editorial assistants The merchant NPC class: If you like being rich better than anything else. Eileen Lucas Barbara G. Young 28 A Room for the Knight Patrick G. Goshtigian and Nick Kopsinis Art director Rating the inns and taverns of fantasy campaign worlds. Roger Raupp 34 Fifty Ways to Foil Your Players Jape Trostle Mad prophets, con men, and adoring monsters to vex your characters. Production staff Betty Elmore OTHER FEATURES Kim Janke Lori Svikel 40 The Curse of the Magus fiction by Bruce Boston and Robert Frazier Subscriptions U.S. Advertising Even in exile, a wizard is still the most dangerous of opponents. Pat Schulz Sheila Meehan 46 Arcane Lure Dan Snuffin U.K. correspondents Recharge: One simple spell with a lifetime of uses. Graeme Morris Rik Rose 54 The Golems Craft John C. Bunnell To build a golem, you first need a dungeon full of money. U.K. advertising Dawn Carter Kris Starr 58 Through the Looking Glass Robert Bigelow A look at convention fun, deadlines, and a siege-tower giant. -

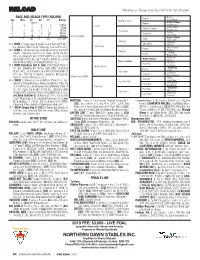

RELOAD 2009 Chestnut - Dosage Profile: 13-7-19-1-0; DI: 2.81; CD: +0.80

RELOAD 2009 Chestnut - Dosage Profile: 13-7-19-1-0; DI: 2.81; CD: +0.80 Nearco RACE AND (BLACK-TYPE) RECORD Nearctic *Lady Angela Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earnings Northern Dancer Native Dancer 2 n uraced Natalma Almahmoud 3 8 1 4 1 1 1 2 ,$250 Danzig Crafty Admiral 4 7 2 0 0 5 , 6 5 94 Admiral’s Voyage Olympia Lou 5 2 ( 12) 0 0 1 91,100 Pas de Nom Petition 6 5 2 0 ( 2 )2 135,500 *Petitioner Steady Aim Hard Spun (2004) 7 2 ( 1) 0 0 0 51,000 Raise a Native Alydar 42 8(2) 4 3 (2) $ 567,504 Sweet Tooth Turkoman Table Play Taba (ARG) At 3, WON a maiden special weight race at Belmont Park (7 Filipina Turkish Tryst fur., defeating Wild Target, Stressing, Love to Run, etc.). Hail to Reason Roberto Bramalea At 4, WON an allowance race at Keeneland (6 fur., by 6 3/4 Darbyvail *My Babu lengths, defeating Casino Dan, Seve, Grand Coulee, Luiana Banquet Bell Reload etc.), an allowance race at Belmont Park (7 fur., equal Polynesian Native Dancer top weight of 122 lbs., by 5 lengths, defeating Escrow Geisha Raise a Native Kid, Inflation Target, Schoolyard Dreams, etc.). Case Ace Raise You Lady Glory At 5, WON Canadian Turf S. [G3] at Gulfstream Park (1 Mr. Prospector *Nasrullah mi., turf, defeating Mr. Online, Salto (IRE), Unbridled Nashua Segula Gold Digger Ocean, etc.), an allowance race at Gulfstream Park (1 Count Fleet Sequence 1/16 mi., turf, by 3 lengths, defeating Bombaguia, Miss Dogwood Hidden Reserve (1994) Kalamos, English Progress, etc.).