Marisa Farrugia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 7 (2021), 2845-2852 Research Article Undermining Colonial Space in Cinematic Discourse

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 7 (2021), 2845-2852 Research Article Undermining Colonial Space In Cinematic Discourse Dr. Ammar Ibrahim Mohammed Al-Yasri Television Arts specialization Ministry of Education / General Directorate of Holy Karbala Education [email protected] Article History: Received: 11 January 2021; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 27 March 2021; Published online: 16 April 2021 Abstract: There is no doubt that artistic races are the fertile factor in philosophy in all of its perceptions, so cinematic discourse witnessed from its early beginnings a relationship to philosophical thought in all of its proposals, and post-colonial philosophy used cinematic discourse as a weapon that undermined (colonial) discourse, for example cinema (Novo) ) And black cinema, Therefore, the title of the research came from the above introduction under the title (undermining the colonial space in cinematic discourse) and from it the researcher put the problem of his research tagged (What are the methods for undermining the colonial space in cinematic discourse?) And also the first chapter included the research goal and its importance and limitations, while the second chapter witnessed the theoretical framework It included two topics, the first was under the title (post-colonialism .. the conflict of the center and the margin) and the second was under the title (post-colonialism between cinematic types and aspects of the visual form) and the chapter concludes with a set of indicators, while the third chapter included research procedures, methodology, society, sample and analysis of samples, While the fourth chapter included the results and conclusions, and from the results obtained, the research sample witnessed the use of undermining the (colonial) act, which was embodied in the face of violence with violence and violence with culture, to end the research with the sources. -

“Al-Tally” Ascension Journey from an Egyptian Folk Art to International Fashion Trend

مجمة العمارة والفنون العدد العاشر “Al-tally” ascension journey from an Egyptian folk art to international fashion trend Dr. Noha Fawzy Abdel Wahab Lecturer at fashion department -The Higher Institute of Applied Arts Introduction: Tally is a netting fabric embroidered with metal. The embroidery is done by threading wide needles with flat strips of metal about 1/8” wide. The metal may be nickel silver, copper or brass. The netting is made of cotton or linen. The fabric is also called tulle-bi-telli. The patterns formed by this metal embroidery include geometric figures as well as plants, birds, people and camels. Tally has been made in the Asyut region of Upper Egypt since the late 19th century, although the concept of metal embroidery dates to ancient Egypt, as well as other areas of the Middle East, Asia, India and Europe. A very sheer fabric is shown in Ancient Egyptian tomb paintings. The fabric was first imported to the U.S. for the 1893 Chicago. The geometric motifs were well suited to the Art Deco style of the time. Tally is generally black, white or ecru. It is found most often in the form of a shawl, but also seen in small squares, large pieces used as bed canopies and even traditional Egyptian dresses. Tally shawls were made into garments by purchasers, particularly during the 1920s. ملخص البحث: التمي ىو نوع من انواع االتطريز عمى اقمشة منسوجة ويتم ىذا النوع من التطريز عن طريق لضم ابر عريضة بخيوط معدنية مسطحة بسمك 1/8" تصنع ىذه الخيوط من النيكل او الفضة او النحاس.واﻻقمشة المستخدمة في صناعة التمي تكون مصنوعة اما من القطن او الكتان. -

Belly Dancing in New Zealand

BELLY DANCING IN NEW ZEALAND: IDENTITY, HYBRIDITY, TRANSCULTURE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Cultural Studies in the University of Canterbury by Brigid Kelly 2008 Abstract This thesis explores ways in which some New Zealanders draw on and negotiate both belly dancing and local cultural norms to construct multiple local and global identities. Drawing upon discourse analysis, post-structuralist and post-colonial theory, it argues that belly dancing outside its cultures of origin has become globalised, with its own synthetic culture arising from complex networks of activities, objects and texts focused around the act of belly dancing. This is demonstrated through analysis of New Zealand newspaper accounts, interviews, focus group discussion, the Oasis Dance Camp belly dance event in Tongariro and the work of fusion belly dance troupe Kiwi Iwi in Christchurch. Bringing New Zealand into the field of belly dance study can offer deeper insights into the processes of globalisation and hybridity, and offers possibilities for examination of the variety of ways in which belly dance is practiced around the world. The thesis fills a gap in the literature about ‘Western’ understandings and uses of the dance, which has thus far heavily emphasised the United States and notions of performing as an ‘exotic Other’. It also shifts away from a sole focus on representation to analyse participants’ experiences of belly dance as dance, rather than only as performative play. The talk of the belly dancers involved in this research demonstrates the complex and contradictory ways in which they articulate ideas about New Zealand identities and cultural conventions. -

Nationalism, Nationalization, and the Egyptian Music Industry: Muhammad Fawzy, Misrphon, and Sawt Al-Qahira (Sonocairo)1

Nationalism, Nationalization, and the Egyptian Music Industry: Muhammad Fawzy, Misrphon, and Sawt al-Qahira (SonoCairo)1 Michael Frishkopf Asian Music, Volume 39, Number 2, Summer/Fall 2008, pp. 28-58 (Article) Published by University of Texas Press DOI: 10.1353/amu.0.0009 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/amu/summary/v039/39.2.frishkopf.html Access Provided by The University of Alberta at 05/08/11 2:13PM GMT Nationalism, Nationalization, and the Egyptian Music Industry: Muhammad Fawzy, Misrphon, and Sawt al-Qahira (SonoCairo)1 Michael Frishkopf Introduction The first large record companies, established in the late 19th century, were based in America, Britain, France, and Germany. By the early 20th century they had already established highly profitable global empires of production and distri- bution (including copious quantities of music recorded far from the corporate bases of power),2 extending along preexisting colonial networks (Gronow 1981, 1983, 56).3 Local challenges (often small, but symbolic) to this productive hegemony arose naturally in tandem with economic and technological development in colonized areas, as well as the rise of independence movements and national consciousness. If the significant forces underlying the appearance of locally owned recording companies among nations recently emerged from colonial domination were largely economic and technological, such developments were often catalyzed and facilitated—if not driven—by nationalist discourses of inde- pendence and self-sufficiency. However, so long as there existed a shared capital- ist framework, the local company might directly cooperate with the global one (for instance, pressing its records locally, or—conversely—sending masters to be pressed abroad).4 But nationalism could assume multiple and contradictory forms. -

1 GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY VISITING FILM SERIES April 29

GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY VISITING FILM SERIES April 29, 2020 I am pleased to be here to talk about my role as Deputy Director of the Washington, DC International Film Festival, more popularly known as Filmfest DC, and as Director of the Arabian Sights Film Festival. I would like to start with a couple of statistics: We all know that Hollywood films dominate the world’s movie theaters, but there are thousands of other movies made around the globe that most of us are totally unaware of or marginally familiar with. India is the largest film producing nation in the world, whose films we label “Bollywood”. India produces around 1,500 to 2,000 films every year in more than 20 languages. Their primary audience is the poor who want to escape into this imaginary world of pretty people, music and dancing. Amitabh Bachchan is widely regarded as the most famous actor in the world, and one of the greatest and most influential actors in world cinema as well as Indian cinema. He has starred in at least 190 movies. He is a producer, television host, and former politician. He is also the host of India’s Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. Nigeria is the next largest film producing country and is also known as “Nollywood”, producing almost 1000 films per year. That’s almost 20 films per week. The average Nollywood movie is produced in a span of 7-10 days on a budget of less than $20,000. Next comes Hollywood. Last year, 786 films were released in U.S. -

A Lost Arab Hollywood: Female Representation in Pre-Revolutionary Contemporary Egyptian Cinema

A LOST ARAB HOLLYWOOD: FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN PRE-REVOLUTIONARY CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN CINEMA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Walsh School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service By Yasmine Salam Washington, D.C. April 20, 2020 2 Foreword This project is dedicated to Mona, Mehry and Soha. Three Egyptian women whose stories will follow me wherever I go. As a child, I never watched Arabic films. Growing up in London to an Egyptian family meant I desperately craved to learn pop-culture references that were foreign to my ancestors. It didn’t feel ‘in’ to be different and as a teenager I struggled to reconcile two seemingly incompatible facets of my identity. Like many of the film characters in this study, I felt stuck at a crossroads between embracing modernity and respecting tradition. I unknowingly opted to be a non-critical consumer of European and American mass media at the expense of learning from the rich narratives emanating from my own region. My British secondary school’s curriculum was heavily Eurocentric and rarely explored the history of my people further than as tertiary figures of the past. That is not to say I rejected my cultural heritage upfront. Women in my family went to great lengths to share our intricate family history and values. My childhood was as much shaped by dinner-table conversations at my Nona’s apartment in Cairo and long summers at the Egyptian coast, as it was by my life in Europe. -

Faten Hamama and the 'Egyptian Difference' in Film Madamasr.Com January 20

Faten Hamama and the 'Egyptian difference' in film madamasr.com January 20 In 1963, Faten Hamama made her one and only Hollywood film. Entitled Cairo, the movie was a remake of The Asphalt Jungle, but refashioned in an Egyptian setting. In retrospect, there is little remarkable about the film but for Hamama’s appearance alongside stars such as George Sanders and Richard Johnson. Indeed, copies are extremely difficult to track down: Among the only ways to watch the movie is to catch one of the rare screenings scheduled by cable and satellite network Turner Classic Movies. However, Hamama’s foray into Hollywood is interesting by comparison with the films she was making in “the Hollywood on the Nile” at the time. The next year, one of the great classics of Hamama’s career, Al-Bab al-Maftuh (The Open Door), Henri Barakat’s adaptation of Latifa al-Zayyat’s novel, hit Egyptian screens. In stark contrast to Cairo, in which she played a relatively minor role, Hamama occupied the top of the bill for The Open Door, as was the case with practically all the films she was making by that time. One could hardly expect an Egyptian actress of the 1960s to catapult to Hollywood stardom in her first appearance before an English-speaking audience, although her husband Omar Sharif’s example no doubt weighed upon her. Rather, what I find interesting in setting 1963’s Cairo alongside 1964’s The Open Door is the way in which the Hollywood film marginalizes the principal woman among the film’s characters, while the Egyptian film sets that character well above all male counterparts. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian Urban Exigencies: Space, Governance and Structures of Meaning in a Globalising Cairo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Roberta Duffield Committee in charge: Professor Paul Amar, Chair Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse Assistant Professor Javiera Barandiarán Associate Professor Juan Campo June 2019 The thesis of Roberta Duffield is approved. ____________________________________________ Paul Amar, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Jan Nederveen Pieterse ____________________________________________ Javiera Barandiarán ____________________________________________ Juan Campo June 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose valuable direction, comments and advice informed this work: Professor Paul Amar, Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Professor Javiera Barandiarán and Professor Juan Campo, alongside the rest of the faculty and staff of UCSB’s Global Studies Department. Without their tireless work to promote the field of Global Studies and committed support for their students I would not have been able to complete this degree. I am also eternally grateful for the intellectual camaraderie and unending solidarity of my UCSB colleagues who helped me navigate Californian graduate school and come out the other side: Brett Aho, Amy Fallas, Tina Guirguis, Taylor Horton, Miguel Fuentes Carreño, Lena Köpell, Ashkon Molaei, Asutay Ozmen, Jonas Richter, Eugene Riordan, Luka Šterić, Heather Snay and Leila Zonouzi. I would especially also like to thank my friends in Cairo whose infinite humour, loyalty and love created the best dysfunctional family away from home I could ever ask for and encouraged me to enroll in graduate studies and complete this thesis: Miriam Afifiy, Eman El-Sherbiny, Felix Fallon, Peter Holslin, Emily Hudson, Raïs Jamodien and Thomas Pinney. -

Alia Mossallam 200810290

The London School of Economics and Political Science Hikāyāt Sha‛b – Stories of Peoplehood Nasserism, Popular Politics and Songs in Egypt 1956-1973 Alia Mossallam 200810290 A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2012 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,397 words (excluding abstract, table of contents, acknowledgments, bibliography and appendices). Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that parts of my thesis were copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Naira Antoun. 2 Abstract This study explores the popular politics behind the main milestones that shape Nasserist Egypt. The decade leading up to the 1952 revolution was one characterized with a heightened state of popular mobilisation, much of which the Free Officers’ movement capitalized upon. Thus, in focusing on three of the Revolution’s main milestones; the resistance to the tripartite aggression on Port Said (1956), the building of the Aswan High Dam (1960- 1971), and the popular warfare against Israel in Suez (1967-1973), I shed light on the popular struggles behind the events. -

Changing News Changing Realities Media Censorship’S Evolution in Egypt

ReuteRs InstItute for the study of JouRnalIsm Changing News Changing Realities media censorship’s evolution in egypt Abdalla F. Hassan Changing News Changing Realities Changing News Changing Realities media censorship’s evolution in egypt Abdalla F. Hassan Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism University of Oxford Research sponsored by the Gerda Henkel Foundation Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Department of Politics and International Relations University of Oxford 13 Norham Gardens Oxford OX2 6PS United Kingdom http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk Copyright © 2013 by Abdalla F. Hassan Design by Sally Boylan and Adam el-Sehemy Cover photographs by Abdalla F. Hassan, Joshua Stacher, and Lesley Lababidi The newspapers’ sting at first seemed slight and was conveniently disregarded, but its cumulative effect proved dangerous. By aggressively projecting political messages to its readers and generating active political debate among an expanding reading public . the press helped create a climate for political action that would eventually undermine the British hold on the country. (Ami Ayalon, The Press in the Arab Middle East) For Teta Saniya, my parents, and siblings with love, and for all those brave souls and unsung heroes who have sacrificed so much so that others can live free Contents Acknowledgments xi Preface:TheStateandtheMedia 1 I: Since the Printing Press 5 1. PressBeginningsinEgypt 7 2. NasserandtheEraofPan-Arabism 29 3. Sadat,theInfitah,andPeacewithIsrael 63 II: The Media and the Mubarak Era 79 4. Mubarak’sThree-DecadeCaretakerPresidency 81 5. Television’sComingofAge 119 6. BarriersBroken:Censorship’sLimits 137 7. FreeExpressionversustheRighttoBark 189 III: Revolution and Two and a Half Years On 221 8. -

154 Features Features 155

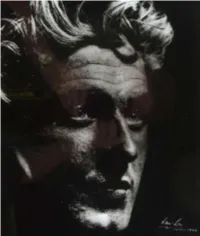

154 Features Features 155 Van Leo from Turkey to Egypt By Martina Corgnati 156 Features The first photographic forays in the Middle East occurred within the Armenian community. In Egypt, legendary figures such as G. Lekegian, who arrived from Istanbul around 1880, kick-started an Armenian led monopoly over photography and the photographic business. Gradually, other photogra- phers began to populate the area around Lekegian’s Cairo studio, located near Opera Square, creating a small “special- ized” neighborhood in both the commercial and ethnic sense. Favored, perhaps, by historical familiarity with images and Christian religion’s acceptance of representational media; Armenians tended to pass on the trade, which at the time could only be learned through experience in the workshops. Due to this process, Armenian photographers were often quite experimental. Armand (Armenak Arzrouni, b. Erzurum 1901 – d. Cairo 1963), Archak, Tartan and Alban (the art name of Aram Arnavoudian, b. Istanbul 1883 – d. Cairo 1961), for example, who arrived in Cairo in the early twentieth century, were some of the first to try “creative” photographic tech- niques that played with variations in composition and points of view. The first photographer Van Leo met in Cairo was an Arme- nian artist called Varjabedian. Still a child, Van Leo regularly visited his provincial photography studio and, years later, Varjabedian would be the one to introduce him to the photog- raphy “temple” in Cairo. This was the name given to the area from Opera Square to Qasr al Nil Street where an abundance of photographic studios and foreign jewelers mingled with Leon (Leovan) Boyadjian, known in the art world as the Egyptian artistic aura. -

Arabic Films

Arabic Films Call # HQ1170 .A12 2007 DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6528747~S7 TITLE 3 times divorced / a film by Ibtisam Sahl Mara'ana a Women Make Movies release First Hand Films produced for The Second Authority for Television & Radio the New Israeli Foundation for Cinema & Film Gon Productions Ltd Synopsis Khitam, a Gaza-born Palestinian woman, was married off in an arranged match to an Israeli Palestinian, followed him to Israel and bore him six children. When her husband divorced her in absentia in the Sharia Muslim court and gained custody of the children, Khitam was left with nothing. She cannot contact her children, has no property and no citizenship. Although married to an Israeli, a draconian law passed in 2002 barring any Palestinian from gaining Israeli citizenship has made her an illegal resident there. Now she is out on a dual battle, the most crucial of her life: against the court which always rules in favor of the husband, and against the state in a last-ditch effort to gain citizenship and reunite with her children Format DVD format Call # DS119.76 .A18 2008 DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6514808~S7 TITLE 9 star hotel / Eden Productions Synopsis A look at some of the many Palestinians who illegally cross the border into Israel, and how they share their food, belongings, and stories, as well as a fear of the soldiers and police Format DVD format Call # PN1997 .A127 2000z DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6482369~S7 TITLE 24 sāʻat ḥubb = 24 hours of love / Aflām al-Miṣrī tuqaddimu qiṣṣah wa-sīnāryū wa-ḥiwār, Fārūq Saʻīd افﻻم المرصي تقدم ؛ قصة وسيناريوا وحوار, فاروق سعيد ؛ / hours of love ساعة حب = ikhrāj, Aḥmad Fuʼād; 24 24 اخراج, احمد فؤاد Synopsis In this comedy three navy officers on a 24 hour pass go home to their wives, but since their wives doubt their loyalty instead of being welcomed they are ignored.