Eat My Dust Georgine Clarsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women, Old and Aware: Living As a Minority in Extended Care Institutions

WOMEN, OLD AND AWARE: LIVING AS A MINORITY IN EXTENDED CARE INSTITUTIONS by Linda-Mae Campbell B.A., The University of Alberta, 1982 B.S.W., The University of Victoria, 1990 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1998 © Linda-Mae Campbell, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. 0 Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) Abstract Women Old And Aware: Living As A Minority In Extended Care Institutions The purpose of this phenomenological study was to describe the everyday lived experiences of old, cognitively intact women, residing in an integrated extended care facility among an overwhelming majority of confused elderly people. The research question was "From your perspective, what is the impact of living in an environment where the majority of residents, with whom you reside, are cognitively impaired?". A purposive sample of five older women participated in multiple in-depth interviews about their subjective experiences. -

Narratives of Motoring in Britain 1896-1930 Esme

Perspectives on the Road: Narratives of Motoring in Britain 1896-1930 Esme Anne Coulbert A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy This research project was carried out in collaboration with the Coventry Transport Museum. October 2013 This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. This thesis benefits from an Arts and Humanities Research Council Collaborative Doctoral Award, established by Nottingham Trent University in conjunction with the Coventry Transport Museum. The museum has supported this project by granting unrestricted access to its archives and records for the purposes of research. Some of the research gathered for this thesis has also featured in exhibitions at the museum and at the Coventry Festival of Motoring. Supervisors: Professor Tim Youngs, Nottingham Trent University Dr Carl Thompson, Nottingham Trent University Steve Bagley, Coventry Transport Museum Acknowledgements I would like to thank first and foremost my fiancé, family and friends for their unrelenting support and patience; and particularly my son who, for the past four years, has only been able to catch mere glimpses of me behind my desk. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank my supervisors Tim and Carl for their time and expert care throughout the duration of this project. -

Kathy Sledge Press

Web Sites Website: www.kathysledge.com Website: http: www.brightersideofday.com Social Media Outlets Facebook: www.facebook.com/pages/Kathy-Sledge/134363149719 Twitter: www.twitter.com/KathySledge Contact Info Theo London, Management Team Email: [email protected] Kathy Sledge is a Renaissance woman — a singer, songwriter, author, producer, manager, and Grammy-nominated music icon whose boundless creativity and passion has garnered praise from critics and a legion of fans from all over the world. Her artistic triumphs encompass chart-topping hits, platinum albums, and successful forays into several genres of popular music. Through her multi-faceted solo career and her legacy as an original vocalist in the group Sister Sledge, which included her lead vocals on worldwide anthems like "We Are Family" and "He's the Greatest Dancer," she's inspired millions of listeners across all generations. Kathy is currently traversing new terrain with her critically acclaimed show The Brighter Side of Day: A Tribute to Billie Holiday plus studio projects that span elements of R&B, rock, and EDM. Indeed, Kathy's reached a fascinating juncture in her journey. That journey began in Philadelphia. The youngest of five daughters born to Edwin and Florez Sledge, Kathy possessed a prodigious musical talent. Her grandmother was an opera singer who taught her harmonies while her father was one-half of Fred & Sledge, the tapping duo who broke racial barriers on Broadway. "I learned the art of music from my father and my grandmother. The business part of music was instilled through my mother," she says. Schooled on an eclectic array of artists like Nancy Wilson and Mongo Santamaría, Kathy and her sisters honed their act around Philadelphia and signed a recording contract with Atco Records. -

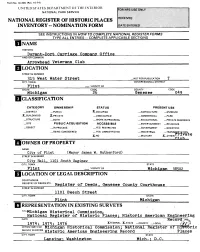

NOMINATION FORM I NAME Durant

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Durant-Dort Carriage Company Office____________ AND/OR COMMON Arrowhead Veterans Club_______________________ LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 315 West Water Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Flint —. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Michigan 26 Genesee 049 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL — TRANSEORTATION, f'T'T' Vfl T A X-NO —MILITARY X_OTHER:rriV<llm iihi ' e OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Flint (Mayor James W. Rutherford) STREET & NUMBER City Hall, 1.101 South Saginaw CITY, TOWN STATE Flint VICINITY OF Michigan U8502 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Registrfir of Deeds» Genesee County Courthouse STREET& NUMBER 1101 Beech Street CITY. TOWN STATE Flint Michigan REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTL1Michigan Historical Commissions National Register of Historic Places; Historic American Engineering DATE Record 1974; 1975; 1976________________XFEDERAL -

Gm Livonia Trim Plant in Livonia, Michigan ______10

Repurposing Former Automotive Manufacturing Sites in the Midwest A report on what communities have done to repurpose closed automotive manufacturing sites, and lessons for Midwestern communities for repurposing their own sites. Prepared by: Valerie Sathe Brugeman, MPP Kristin Dziczek, MS, MPP Joshua Cregger, MS Prepared for: The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation June 2012 Repurposing Former Midwestern Automotive Manufacturing Sites A report on what communities have done to repurpose closed automotive manufacturing sites, and lessons for Midwestern communities for repurposing their own sites. Report Prepared for: The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation Report Prepared by: Center for Automotive Research 3005 Boardwalk, Ste. 200 Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Valerie Sathe Brugeman, MPP Kristin Dziczek, MS, MPP Joshua Cregger, MS Repurposing Former Midwestern Automotive Manufacturing Sites Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS _____________________________________________________________ III About the Center for Automotive Research ______________________________________________ iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY _____________________________________________________________ 4 Case Studies ______________________________________________________________________ 5 Key Findings _______________________________________________________________________ 5 INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 7 METHODOLOGY __________________________________________________________________ 7 GM LIVONIA TRIM PLANT IN LIVONIA, MICHIGAN _______________________________________ -

Disco Top 15 Histories

10. Billboard’s Disco Top 15, Oct 1974- Jul 1981 Recording, Act, Chart Debut Date Disco Top 15 Chart History Peak R&B, Pop Action Satisfaction, Melody Stewart, 11/15/80 14-14-9-9-9-9-10-10 x, x African Symphony, Van McCoy, 12/14/74 15-15-12-13-14 x, x After Dark, Pattie Brooks, 4/29/78 15-6-4-2-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-3-3-5-5-5-10-13 x, x Ai No Corrida, Quincy Jones, 3/14/81 15-9-8-7-7-7-5-3-3-3-3-8-10 10,28 Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us, McFadden & Whitehead, 5/5/79 14-12-11-10-10-10-10 1,13 Ain’t That Enough For You, JDavisMonsterOrch, 9/2/78 13-11-7-5-4-4-7-9-13 x,89 All American Girls, Sister Sledge, 2/21/81 14-9-8-6-6-10-11 3,79 All Night Thing, Invisible Man’s Band, 3/1/80 15-14-13-12-10-10 9,45 Always There, Side Effect, 6/10/76 15-14-12-13 56,x And The Beat Goes On, Whispers, 1/12/80 13-2-2-2-1-1-2-3-3-4-11-15 1,19 And You Call That Love, Vernon Burch, 2/22/75 15-14-13-13-12-8-7-9-12 x,x Another One Bites The Dust, Queen, 8/16/80 6-6-3-3-2-2-2-3-7-12 2,1 Another Star, Stevie Wonder, 10/23/76 13-13-12-6-5-3-2-3-3-3-5-8 18,32 Are You Ready For This, The Brothers, 4/26/75 15-14-13-15 x,x Ask Me, Ecstasy,Passion,Pain, 10/26/74 2-4-2-6-9-8-9-7-9-13post peak 19,52 At Midnight, T-Connection, 1/6/79 10-8-7-3-3-8-6-8-14 32,56 Baby Face, Wing & A Prayer, 11/6/75 13-5-2-2-1-3-2-4-6-9-14 32,14 Back Together Again, R Flack & D Hathaway, 4/12/80 15-11-9-6-6-6-7-8-15 18,56 Bad Girls, Donna Summer, 5/5/79 2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-10-13 1,1 Bad Luck, H Melvin, 2/15/75 12-4-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-4-5-5-7-10-15 4,15 Bang A Gong, Witch Queen, 3/10/79 12-11-9-8-15 -

Corporate Impersonation: the Possibilities of Personhood in American Literature, 1886-1917

Corporate Impersonation: The Possibilities of Personhood in American Literature, 1886-1917 by Nicolette Isabel Bruner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee Professor Gregg D. Crane, Chair Professor Susanna L. Blumenthal, University of Minnesota Professor Jonathan L. Freedman Associate Professor Scott R. Lyons “Everything…that the community chooses to regard as such can become a subject—a potential center—of rights, whether a plant or an animal, a human being or an imagined spirit; and nothing, if the community does not choose to regard it so, will become a subject of rights, whether human being or anything else.” -Alexander Nékám, 1938 © Nicolette Isabel Bruner Olson 2015 For my family – past, present, and future. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support of my committee: Gregg Crane, Jonathan Freedman, Scott Lyons, and Susanna Blumenthal. Gregg Crane has been a constant source of advice and encouragement whose intimate knowledge of law and literature scholarship has been invaluable to my own development as a scholar. Jonathan Freedman’s class on “Fictions of Finance” inspired much of the work in this dissertation, as did Susanna Blumenthal’s seminar on “The Concept of the Person” during my time at the University of Michigan Law School. Jonathan’s good humor, grace, and sympathetic yet critical eye have profoundly shaped my work. As I have expanded my research into animal studies, Scott Lyons guided me to new intellectual domains. Finally, ever since I began working with her during my first year of law school, Susanna has been a source of wisdom, encouragement, and generosity. -

A Marvel of Mechanical Perfection

NEW-YORK DAILY TRIBUiSnE,'\u25a0 SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, 1909. s Automobiles. 'Automobile*. Automobiles. Automobile*. Automobiles. 'Automobile*. —--^ "-^ \^y I? Limited t ! A Marvel of Mechanical Perfection. \u25a0 —IIWIIM \u25a0\u25a0\u25a0\u25a0 I\u25a0\u25a0111111111111 l\ • Where in other cars the jolts and jars must be taken up by spring* and We know of one owner of an Oldsmobile Limited wlio has run his car Oldsmobile Limited is equipped withTooring, Roadster, Close- Coupled shock absorbers, in the Oldsmobile Limited we do away with most of them over 12.000 miles, over all kind* of roads. And the tires even now show or Limousine Body. Price equipped with 9 inch Head Lights, Presto-Lite ether. For we have used wheels 42 inches in diameter, front and rear, but little sign of wear. Gas Light, Side and Tail Lamps of the most improved type, horn, with fall with 4io inch tires all around. But the 42 inch Wheels arc only nnr of the many superiori- set of tools, $4,600. F. O. B. Lansing, Michigan. They are nearly Jinrikisha o\ir Salesroom, Broadway, to the size of the Tinrikisha wheels, noted for their easy ties of the Oldsmobile Limited. You are cordially invited to 1653 see lor riding qualities. They are so large that they bridge over all but the widest yourself its style, graceful beauty and exqxiisite finish. A Demonstration ruts, ik the extra 54% tire capacity afforded by the larger wheels- gives A Wonderfully Flexible Motor to you willprove its easy riding qualities. , ?o much more resiliency that you pass unshaken over the minor ruts and The motor i^ so flexible that you ran take any hill,plow through mud The Oldsmobile Special bump? that the ordinary transmit wheels to the chassis. -

99 News Profile

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN PILOTS 3 3h e m s ~ < AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 1973 The wind donee did it ! ih e HO iw iu s AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 1973 VOLUME 15 NUMBER 7 THE NINETY-NINES, INC. The Will Rogers World Airport International Headquarters International President Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73159 Return Form 3579 to above address 2nd Class Postage pd. at North Little Rock. Ark. As I left Toronto last year my mind was filled with fresh Publisher Lee Keenihan memories of the Hyatt-Regency, Fox-Den Farms, Button- Managing Editor..........................Mardo Crane ville, Canadian customs and all the 99s who made the Assistant E d ito r............................. Betty Hicks convention a tremendous success. On the way home I Art Director Betty Hagerman realized what a great challenge there was in the year a- Production Manager Ron Oberlag head tor the 99s and for me as President. The exciting Circulation Manager Loretta Gragg goals proposed offered a new opportunity to widen hori zons and strengthen the impact of the organization on the Contributing Editors........................Mary Foley aviation community. Virginia Thompson In September, I attended the South Central Section Director of Advertising.............. Maggie Wirth meeting in Dallas as the first official function; this was followed by the North Central Section meeting in Illinois. Susie Sewell The Sacramento chapter members in California cele brated the 25th anniversary of the founding of their chap Contents ter on November 17th and it was a joy to share with them the review of their Powder Puff Derby — Highlights & Results 2-5 many accomplishments. -

Frühaufsteher 158 Titel, 11,6 Std., 1,02 GB

Seite 1 von 7 -FrühAufsteher 158 Titel, 11,6 Std., 1,02 GB Name Dauer Album Künstler 1 Africa 3:36 Best Of Jukebox Hits - Comp 2005 (CD3-VBR) Laurens Rose 2 Agadou 3:22 Oldies Saragossa Band 3 All american girls 3:57 The Very Best Of - Sister Sledge 1973-93 (RS) Sister Sledge 4 All right now 5:34 Best Of Rock - Comp 2005 (CD1-VBR) Free 5 And the beat goes on 3:26 1000 Original Hits 1980 - Comp 2001 (CD-VBR) The Whispers 6 Another brick in the wall 3:11 Music Of The Millenium II - Comp 2001 (CD1-VBR) Pink Floyd 7 Automatic 4:48 Best Of - The Pointer Sisters - Comp 1995 (CD-VBR) The Pointer Sisters 8 Bad girls 4:55 Bad Girls - Donna Summer - 1979 (RS) Summer Donna 9 Best of my love 3:40 Dutch Collection Earth, Wind & Fire 10 Big bamboo (Ay ay ay) 3:55 Best of Saragossa Band Saragossa Band 11 Billie Jean 4:54 History 1 - Michael Jackson - Comp 1995 (CD-VBR) Jackson Michael 12 Black & white 3:41 Single A Patto 13 Blame it on the boogie 3:35 Good Times - Best Of 70s - Comp 2001 (CD2-VBR) Jackson Five 14 Boogie on reggae woman 4:56 Fulfillingness' First Finale - Stevie Wonder - 1974 (RS) Wonder Stevie 15 Born to be alive 3:09 Afro-Dite Väljer Sina Discofav Hernandez Patrick 16 Break my stride 3:00 80's Dance Party Wilder Matthew 17 Carwash 3:19 Here Come The Girls - Sampler (RS) Royce Rose 18 Celebration 4:59 Mega Party Tracks 06 CD1 - 2001 Kool & The Gang 19 Could it be magic 5:18 A Love Trilogy - Donna Summer - 1976 (RS) Summer Donna 20 Cuba 3:49 Hot & Sunny - Comp 2001 (CD) Gibson Brothers 21 D.I.S.C.O. -

USA Price List (.PDF File)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA JOHN L. KIMBROUGH 10140 Wandering Way Benbrook Texas 76126 USA Internet Web Site: www.jlkstamps.com 20 JAN 2016 Telephone: 817-249-2447 FAX: 817-249-5213 E-mail: [email protected] Price-List of USA STAMPS 1929 - 2000 Listing ends with stamps issued through 2000 Contents: Sales Policies and How to Order Page 2 Commemoratives, Year Sets, Regular Issues 1929-2000 Pages 3-13 Great Americans Series Regular Issues 1980-1999 Page 14 Flora and Fauna Series Regular Issues 1990-2000 Page 14 Modern Official Regular Issues 1983-1999 Page 14 Regular Issue Coil Stamps 1920-2000 Pages 15-16 Air Mail Coils 1948-1976 Page 17 Transportation Coil Series 1981-1995 Page 18 Modern Official Coils 1983-2000 Page 18 Air Mail Regular Issues1926-2000 Page 19 Member: 1. ASDA -- American Stamp Dealer’s Association 2. APS -- American Philatelic Society 3. CSA -- Confederate Stamp Alliance 4. TSDA -- Texas Stamp Dealer’s Association 5. FSDA -- Florida Stamp Dealer’s Association 6. AAPE -- American Association of Philatelic Exhibitors 7. USPCS -- US Philatelic Classics Society Thank you very much for your interest. John L. Kimbrough Sales Policies and How to Order 1. Orders from this USA Listing may be made by mail, FAX, telephone, or E-mail ([email protected]). If you have Internet access, the easiest way to order is to visit my web site (http://www.jlkstamps.com) and use my secure Visa/Mastercard on-line credit card order form. 2. Please order using the Scott Numbers only (may also use a description of the stamp as well). -

United States Women in Aviation Through World War I

United States Women in Aviation through World War I Claudia M.Oakes •^ a. SMITHSONIAN STUDIES IN AIR AND SPACE • NUMBER 2 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given sub stantive review.