Oral History of Herbert F. Mataré

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Research Working Paper No. 27

Economic Research Working Paper No. 27 Breakthrough technologies – Semiconductor, innovation and intellectual property Thomas Hoeren Francesca Guadagno Sacha Wunsch-Vincent Economics & Statistics Series November 2015 Breakthrough Technologies – Semiconductors, Innovation and Intellectual Property Thomas Hoeren*, Francesca Guadagno**, Sacha Wunsch-Vincent** Abstract Semiconductor technology is at the origin of today’s digital economy. Its contribution to innova- tion, productivity and economic growth in the past four decades has been extensive. This paper analyzes how this breakthrough technology came about, how it diffused, and what role intellec- tual property (IP) played historically. The paper finds that the semiconductor innovation ecosys- tem evolved considerably over time, reflecting in particular the move from early-stage invention and first commercialization to mass production and diffusion. All phases relied heavily on con- tributions in fundamental science, linkages to public research and individual entrepreneurship. Government policy, in the form of demand-side and industrial policies were key. In terms of IP, patents were used intensively. However, they were often used as an effective means of sharing technology, rather than merely as a tool to block competitors. Antitrust policy helped spur key patent holders to set up liberal licensing policies. In contrast, and potentially as a cautionary tale for the future, the creation of new IP forms – the sui generis system to protect mask design - did not produce the desired outcome. Finally, copyright has gained in importance more re- cently. Keywords: semiconductors, innovation, patent, sui generis, copyright, intellectual property JEL Classification: O330, O340, O470, O380 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Intellectual Property Organization or its member states. -

Federico Capasso

Federico Capasso ADDRESS: John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Harvard University 205 A Pierce Hall 29 Oxford Street Cambridge MA 02138 PHONE: (617) 384-7611 FAX: (617) 495-2875 EMAIL: [email protected] PERSONAL: Married; two children CITIZENSHIP: Italian and U.S. (Naturalized; 09/23/1992) EDUCATION: 1973 Doctor of Physics, Summa Cum Laude University of Rome, La Sapienza, Italy 1973-1974 Postdoctoral Fellow Fondazione Bordoni, Rome, Italy ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Jan. 2003- Present Robert Wallace Professor of Applied Physics Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering, John A. Paulson, School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS: 2000 – 2002 Vice President of Physical Research, Bell Laboratories Lucent Technologies, Murray Hill, NJ 1997- 2000 Department Head, Semiconductor Physics Research, Bell Laboratories Lucent Technologies, Murray Hill, NJ. 1987- 1997 Department Head, Quantum Phenomena and Device Research, Bell Laboratories Lucent Technologies (formerly AT&T Bell Labs, until 1996), Murray Hill, NJ 1984 – 1987 Distinguished Member of Technical Staff, Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, NJ 1977 – 1984 Member of Technical Staff, Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, NJ 1976 – 1977 Visiting Scientist, Bell Laboratories, Holmdel, NJ 1974 – 1976 Research Physicist, Fondazione Bordoni, Rome, Italy Citations (Google Scholar) Over 93000 H-index (Google Scholar) 144 Publications Over 500 hundred peer reviewed journals Patents 70 US patents KEY ACHIEVEMENTS 1. Bandstructure Engineering and Quantum Cascade Lasers (QCLs) Capasso and his Bell Labs collaborators over a 20-year period pioneered band-structure engineering, a technique to design and implement artificially structured (“man-made”) semiconductor, materials, and related phenomena/ devices, which revolutionized heterojunction devices in photonics and electronics. -

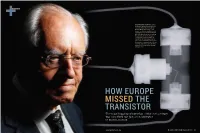

HOW EUROPE MISSED the TRANSISTOR the Most Important Invention of the 20Th Century Was Conceived Not Just Once, but Twice by MICHAEL RIORDAN

HISTORY INVENTION AND INVENTORS: In Paris, + shortly after World War II, two German scientists, Herbert Mataré [left] and Heinrich Welker, invented the “tran- sistron,” a solid-state amplifier remark- ably similar to the transistor developed by Bell Telephone Laboratories at about the same time. In this X-ray image of a commercial transistron built in the early 1950s, two closely spaced metal point contacts, one from each end, touch the surface of a germanium sliver. A third electrode contacts the other side of the sliver. Mataré is now retired and living in Malibu, Calif. HOW EUROPE MISSED THE TRANSISTOR The most important invention of the 20th century was conceived not just once, but twice BY MICHAEL RIORDAN www.spectrum.ieee.org November 2005 | IEEE Spectrum | INT 47 At the time, German radar systems operated at wavelengths as those made of silicon, which seemed best suited for microwave short as half a meter. But the systems could not work at shorter reception. But the Allied bombing of Berlin was making life exceed- wavelengths, which would have been better able to discern smaller ingly difficult for Telefunken researchers. “I spent many hours in targets, like enemy aircraft. The problem was that the vacuum- subway stations during bomb attacks,” he wrote in an unpublished tube diodes that rectified current in the early radar receivers could memoir. So in January 1944, the company shifted much of its radar not function at the high frequencies involved. Their dimensions— research to Breslau in Silesia (now Wroclaw, Poland). Mataré worked especially the gap between the diode’s anode and cathode—were in an old convent in nearby Leubus. -

Science in Song

NO. 86: JUNE 2008 ISSN: 1751-8261 Contents Science in song Main feature 1 Science in song Melanie Keene considers the yield of the Outreach and Education BSHS grants report 4 project on songs that reflect, satirise and celebrate science. A reception study? 5 Reports of Meetings 6 ‘Oh! have you heard the news of late, reach and Education Committee has been About our great original state; collecting examples of scientific songs from BSHS Postgrad Conference If you have not, I will relate the past two hundred years. Ranging across BSLS The grand Darwinian theory…’ historical periods, geographic locations, musi- Imperial & Colonial Medicine cal and lyrical genres, disciplinary divisions, Wrexham Science Festival How did you first come to hear about the and degrees of expertise, many different theory of evolution? For many children at the cultures have embraced the choral possibili- Reviews 9 end of the 19th century it was through The ties of the natural and technological worlds. ‘Undead controversies’ 10 Scottish Students’ Songbook and John Young’s Encompassing everything from 17th-century scientific song ‘The Grand Darwinian Theory’. ballads on fen drainage to Jingle Bells rewrit- The questionnaire 10 But why was a member of the Perthshire ten as a carol celebrating lipid biochemistry, BSHS news 12 Society of Natural Science writing such lyrics? this diverse array of tunes and lyrics was What is the history of science in song? composed by figures from the well-known News 14 Over the last few months the BSHS Out- Irving Berlin to the rather more mysteriously- Listings 15 BJHS, Viewpoint details 16 Editorial This issue is again kicked off with an excel- lent leading article, this time by Melanie Keene on ‘scientific’ songs. -

Administrative Services Building Rm 2072 Color Multi-20190610100738

SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA June 2019 ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 1. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, with tenure. (1) Chai, Joyce Y., professor of electrical engineering and computer science, with tenure, College of Engineering, effective September 1, 2019. (2) Fryberg, Stephanie A., professor of psychology, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective September 1, 2019. (3) Gregg IV, Robert D., associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science, with tenure, College of Engineering, effective September 1, 2019. (4) Gulani, Vikas, Ph.D., M.D., chair, Department of Radiology, professor of radiology, with tenure, effective July 1, 2019, and Fred Jenner Hodges Professor of Radiology, Medical School, effective July 1, 2019 through August 31, 2024. (5) Hughes, Amy E., associate professor of theatre and drama, with tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective September 1, 2019. (6) Maguire-Jack, Kathryn, associate professor of social work, with tenure, School of Social Work, effective September 1, 2019. (7) Pfeffer, Fabian T., promotion to associate professor of sociology, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective September 1, 2019 (currently assistant professor of sociology). (8) Seiberlich, Nicole, Ph.D., associate professor of radiology, with tenure, associate professor of internal medicine, without tenure, Medical School, and associate professor of biomedical engineering, without tenure, Medical School and College of Engineering, effective July 1, 2019. (9) Wexler, Lisa Marin, professor of social work, with tenure, School of Social Work, effective September 1, 2019. (10) Ying, Lei, professor of electrical engineering and computer science, with tenure, College of Engineering, effective September 1, 2019. -

Oyo-Buturi International

Oyo-Buturi International Interview the jacg Technological Contribution “significant contributions in technological Award in commemoration of jacg’s 20th aspects of crystal growth” at the 12th Inter- An interview with Professor Isamu Aka- Anniversary, for outstanding achievements national Conference on Crystal Growth. saki of Meijo University, pioneer in the concerned with the epitaxial growth of Furthermore, in December 1998, Pro- field of semiconducting GaN (gallium compound semiconductor crystals”. fessor Akasaki will be presented the ieee nitride) and related devices. In 1995, Professor Akasaki went on to Jack A. Morton Award at the iedm for “con- receive both the International Symposium tributions in the field of group iii nitride Professor Akasaki was born in Kagoshima, on Compound Semiconductors Award and materials and devices” and the British Rank Kyushu. He received his bachelor’s degree the Heinrich Welker Gold Medal “for his Prize for his great contributions to opto- from Kyoto University in 1952 and his doc- pioneering and outstanding contributions electronics. toral degree in Electronic Engi- It could be said that the semi- neering in 1964 from Nagoya conductor industry is going University. In 1952, he joined through a “blue period”. This Kobe Kogyo Corporation (now “blue period” is one of great ex- Fujitsu Ltd.) and then moved citement and expectation for re- to Nagoya University, where he searchers, businesses and society held the positions of research as a whole. The use of semicon- associate and assistant professor ducting GaN in the fabrication before being appointed an asso- of leds and blue light-emitting ciate professor in 1964. lasers has at last enabled us to see From 1964 to 1981, Profes- our way to realising full-colour sor Akasaki was Head of the displays, highly energy efficient Fundamental Research Labora- traffic lights, ultra high-density tory and General Manager of optical storage systems. -

Transistor 1 Transistor

Transistor 1 Transistor A transistor is a semiconductor device used to amplify and switch electronic signals and electrical power. It is composed of semiconductor material with at least three terminals for connection to an external circuit. A voltage or current applied to one pair of the transistor's terminals changes the current through another pair of terminals. Because the controlled (output) power can be higher than the controlling (input) power, a transistor can amplify a signal. Today, some transistors are packaged individually, but many more are found embedded in integrated circuits. The transistor is the fundamental building block of modern electronic devices, and is ubiquitous in modern electronic systems. Following its development in the early 1950s, the transistor revolutionized the field of electronics, and paved the way for smaller and cheaper radios, calculators, and computers, among other Assorted discrete transistors. things. Packages in order from top to bottom: TO-3, TO-126, TO-92, SOT-23. History The thermionic triode, a vacuum tube invented in 1907, propelled the electronics age forward, enabling amplified radio technology and long-distance telephony. The triode, however, was a fragile device that consumed a lot of power. Physicist Julius Edgar Lilienfeld filed a patent for a field-effect transistor (FET) in Canada in 1925, which was intended to be a solid-state replacement for the triode.[1][2] Lilienfeld also filed identical patents in the United States in 1926[3] and 1928.[4][5] However, Lilienfeld did not publish any research articles about his devices nor did his patents cite any specific examples of a working prototype. -

Lessons Learnt from the Semiconductor Chip Industry and Its IP Law Framework, 32 J

The John Marshall Journal of Information Technology & Privacy Law Volume 32 Issue 3 Article 2 Spring 2016 The Protection of Pioneer Innovations – Lessons Learnt from the Semiconductor Chip Industry and its IP Law Framework, 32 J. Marshall J. Info. Tech. & Privacy L. 151 (2016) Thomas Hoeren Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/jitpl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Computer Law Commons, European Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Privacy Law Commons, Science and Technology Law Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas Hoeren, The Protection of Pioneer Innovations – Lessons Learnt from the Semiconductor Chip Industry and its IP Law Framework, 32 J. Marshall J. Info. Tech. & Privacy L. 151 (2016) https://repository.law.uic.edu/jitpl/vol32/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The John Marshall Journal of Information Technology & Privacy Law by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROTECTION OF PIONEER INNOVATIONS – LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE SEMICONDUCTOR CHIP INDUSTRY AND ITS IP LAW FRAMEWORK THOMAS HOEREN* 1. INTRODUCTION In the second half of the 20th century, semiconductor technology as integrated circuits (IC), commonly known as microchips, became more and more dominating in our lives. Microchips are the control center of simple things like toasters as well as of complex high-tech machines for medical use. -

Japan-Sweden Science, Technology & Innovation Symposium 2014

Japan-Sweden Science, Technology & Innovation Symposium 2014 Biography of Isamu Akasaki (as of April, 2014) Isamu Akasaki received B.S. in 1952 from Kyoto University and Dr. Eng.(Electronics) in 1964 from Nagoya University. In 1964 he became the Head of Basic Research Lab. IV at Matsushita Research Institute Tokyo, Inc. In 1981 he was appointed a professor, in 1992 a Professor Emeritus and in 2004 a University Professor of Nagoya University. Since 1992 he has been a professor at Meijo University, where in 2010 he was appointed a Lifetime Professor. In 1986, he and his group created semiconductor-grade high-quality single crystal of GaN, and in 1989 developed GaN p-n junction blue LED, both for the first time. In 1989 to1991 they succeeded in conductivity control of p- and n-type GaN and nitride alloys of excellent-quality as world firsts, allowing the use of heterostructures and multiple quantum wells(MQWs) in the design of more efficient p-n junction light-emitting structures. In 1990 they achieved the stimulated emission from the high-quality GaN first at room temperature with one order of magnitude lower optical power than before. In 1996 they developed a laser diode (LD) with AlGaN/GaN/GaInN QW device at 376nm, which was the shortest wavelength at that time. They verified in 1991 quantum size effect, in 1997 quantum confined Stark effect in the nitride system. In 2000 they succeeded in crystal orientation control to reduce or even completely eliminate the polarization fields showing the existence of non-/semi-polar nitride crystal planes. -

How Bell Lab

IEEE Spectrum: How Bell Labs Missed the Microchip http://spectrum.ieee.org/computing/hardware/how-bell-labs-missed-the-m... COMPUTING // HARDW ARE How Bell Labs Missed the Microchip The man who pioneered the transistor never appreciated its full potential BY MICHAEL RIORDAN // DECEMBER 2006 At 4:15 a.m. on 11 December 1971, firemen extinguishing an automobile blaze in the New Jersey hamlet of Neshanic Station were shocked to discover a badly charred body slumped face-down in the back seat. It proved to be the remains of Jack A. Morton, the vice president of electronic technology at Bell Telephone Laboratories, in Murray Hill, N.J. He had last been seen talking with two men at the nearby Neshanic Inn just before its 2 a.m. closing--about 100 meters from the abandoned railroad tracks where his flaming Volvo sports coupe was spotted. Local police quickly arrested and booked the men for murder. PHOTO COURTESY OF AT&T ARCHIVES AND HISTORY CENTER This gruesome slaying ended the stellar career of the man who had led Bell Labs’ effort to transform the transistor from a promising but rickety laboratory gizmo into the sturdy, reliable commercial product that eventually revolutionized electronics. During the 1950s and 1960s, Bell Labs’ golden age, Morton served as quarterback of the device development team, making nearly all the key calls on which technologies to pursue and which to forgo. He was a bold, forceful, decisive manager who didn’t suffer fools gladly. And with some of the world’s most intelligent and innovative researchers working for him, he rarely had to. -

The Early Days of Gaas Ics -..~ Rory Van Tuyl's Website

The Early Days of GaAs ICs Rory L. Van Tuyl, Fellow, IEEE Europe improved the GaAs MESFET’s performance until, by Abstract —This article recounts the author’s experiences in the the early 1970s when it became possible to fabricate devices period 1972 – 1982, when GaAs ICs were new, technology was with 1µm gate lengths, GaAs MESFETs emerged as the first 3- still developing, and each new result was the first of its kind. terminal device capable of useful microwave amplification [11- 14]. Index Terms —Gallium Arsenide, High-Speed Integrated Circuits, Integrated Circuit Fabrication, History. By 1972, all the elements were in place. GaAs ICs were waiting to be born. I. INTRODUCTION II. THE RESEARCH PHASE IMING is everything. By the 1970s the world was ready A. The First Circuits for GaAs ICs, and I was privileged to play a part in T In mid-1972, while working as an IC and RF/Microwave bringing them into existence. It had all started a century before design engineer at Hewlett Packard’s Santa Clara Division, I when, in 1871, Dmitri Mendeleev predicted there should be a contacted Charles Liechti at the Company’s central research metallic element to fill the vacant position #31 in his Periodic facility, HP Labs. Charles had recently reported HP’s first Table of the Elements . In 1874 Frenchman Paul Émile LeCoq GaAs MESFET [14], and I was interested to see how this identified this element via spectroscopic analysis of zincblende device might perform as a high-speed switch. (These ore, and named it Gallium. But Gallium does not occur in MESFETs boasted f =15 GHz, versus 2 GHz for Si bipolar elemental form in nature, so it had to be laboriously extracted T transistors of the time). -

Seibersdorf, 26

Professor Dr. Wolfgang Knoll Professional Career 1973 Diploma - Physics, Technical University of Karlsruhe 1976 Ph.D. - Biophysics, University of Konstanz 1976-1977 Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Konstanz 1977-1980 Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Ulm 1980-1981 Postdoctoral Fellow, IBM Res Laboratory, San José, CA 1981 Visiting Scientist, Institute Laue-Langevin, Grenoble, FR 1981-1986 Assistant Professor, Technical University of Munich 1985 Visiting Scientist, IBM Res. Laboratory, San José, CA 1986 Habilitation in Experimental Physics, Technical University of Munich 1986-1991 Young Investigator/Associate Professor, Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research, Mainz 1988 Visiting Scientist, Optical Sciences Center, Tucson, AZ 1990 Visiting Scientist, Dept. of Chem. & Nuc. Engineering, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 1990-1991 Visiting Professor, University of Erlangen 1991-1999 Head of Laboratory for Exotic Nano-Materials, Frontier Research Program, RIKEN-Institute, Japan 1998-2012 Consulting Professor, Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 1993-2008 Director, Max-Planck-Institut für Polymerforschung, Mainz since 1998 Professor (by Courtesy) Chemistry Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL since 1999 Adjunct Professor, Hanyang University, Korea 1999-2003 Temasek Professor, National University of Singapore 2004-2013 Visiting Principal Scientist, Institute of Materials Research and Engineering, Singapore since 2008 Scientific Managing Director, AIT Austrian Institute of Technology