Ozark Jubilee: the Impact of a Regional Identity at a Crossroads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] KÜNSTLER George McCormick and Earl Aycock TITEL Better Stop, Look And Listen Gonna Shake This Shack Tonight LABEL Bear Family Records KATALOG # BCD 17121 PREIS-CODE AH EAN-CODE ÆxAKABMRy171214z ISBN-CODE 978-3-89916-541-8 FORMAT 1 CD Digipack mit 40-seitigem Booklet GENRE Country / Rockabilly ANZAHL TITEL 29 SPIELDAUER 66:06 G Endlich die erste CD-Wiederveröffentlichung von George und Earl, einem der klassischen Hillbilly-Duos! G 29 Top-Titel aus den 50ern, eingespielt in Nashville mit Musikern u.a. aus der Band von Hank Williams und des A-Teams! G Mit allen sechs 78er-Platten von George McCormick und Earl Aycock sowie sechs Singles von George McCormick. G Sweet Little Miss Blue Eyes und If You Got Anything Good werden häufig als zwei der besten Country-Duette aller Zeiten bezeichnet. G Drei der Songs sollte eigentlich Hank Williams aufnehmen, der dann aber starb. G George McCormick war musikalischer Kopf von Porter Wagoners Wagonmasters und Dolly Partons erster Duettpartner in Wagoners TV-Show. G Earl Aycock arbeitete später als DJ in Texas und Louisiana. G Zur CD gehört ein 40-seitiges Booklet von Martin Hawkins; es enthält unveröffentlichte Interviews mit George McCormick. INFORMATIONEN Diese CD präsentiert zwei sehr unterschiedliche Sänger und Musiker, die in nur zwei Jahren einige der besten und interessante- sten Aufnahmen der 1950er-Jahre eingespielt haben. Der damals noch vorherrschende Hank-Williams-Sound machte nur lang- sam Platz für neue Strömungen innerhalb der populären Country Music und des aufkommenden Rockabilly. -

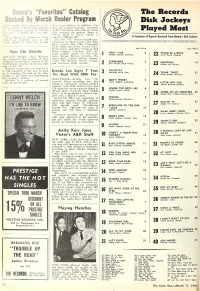

The Records Disk Jockeys Played Most

) ) Dacca’s “Favorites” Catalog The Records Backed By March Bealer Program Disk Jockeys NEW YORK—Deeca Records is of- from local distribs. In addition, win- fering dealers a March sales program dow and counter displays, consumer on its complete catalog of “Golden leaflets and other sales aids are avail- Played Most Favorites,” including nine new addi- able, carrying the general theme of tions. “Every Song In Every Album A A Summary of Reports Received from Nation’s Disk Up to March 24, dealers are being One-In- A-Million Hit.” Jockeys offered an incentive plan on the The new “GF” albums include per- series, details of which can be had formances by Bing Crosby, The Mills lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll Bros., Lenny Dee, Ella Fitzgerald, Kitty Wells, Red Foley, Ernest Tubb, Webb Pierce and Kitty Wells & Red Last Week Last Week Foley (duets). Previous “GF” al- New Chi Distrib PONY TIME 2 bums include stints by The Four WINGS OF A DOVE 18 1 Chubby Checker (Parkway) Sams Ferlin Husky (Capitol) CHICAGO—William (Bill) McGuire Aces, Teresa Brewer (Coral), The has announced the opening of Con- Ames Bros., Jackie Wilson (Bruns- Record Sales, located at 101 wick), The McGuire Sisters (Coral) solidated SURRENDER 3 EMOTIONS 19 and Lawrence Welk (Coral). Elvis Presley (RCA Victor) 09 South Cicero Avenue, on the far west 2 MW Brenda Lee (Decca) side of this city. McGuire stated that now that he is in full operation at his new location Brenda Lee Signs 7 Year CALCUTTA 1 Lawrence Welk (Dot) THINK TWICE 31 he is spending the bulk of his time 3 OA Pic Deal With 20th Fox Am *1 Brook Benton (Mercury) calling on the trade and formulating his company’s policies. -

Country Music Country Music in Missouri Country Bios

Country Music Country music is a genre of popular music that originated in the rural South in the 1920s, with roots in fiddle music, old-time music, blues and various types of folk music. Originally called “hillbilly music” and sometimes called “country and western,” the name “country music” or simply “country” gained popularity in the 1940s. Many recent country artists use elements of pop and rock. Country music often consists in ballads with simple forms and harmonies, accompanied by guitar or banjo with a fiddle. Country bands now often include a steel guitar, bass and drums. Country Music in Missouri Missourians love country music, as evidenced by the large number of country music radio stations, the number of country artists on festivals and presented by concert venues around the state, the country music artists who make their home and perform regularly in the popular tourist destination of Branson, Missouri, and the many Missouri musicians and bands who play country music in the bars and clubs in their local community. “The Sources of Country Music,” a painting by well-known Missouri artist Thomas Hart Benton hangs in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville. Ralph Peer (1892-1960), born in Independence, Missouri, worked for Columbia Records in Kansas City until 1920 when he took a job for OKeh Records in New York and supervised the recording of “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith, the first blues recording aimed at African- Americans. In 1924 he supervised the first commercial recording session in New Orleans, recording jazz, blues and gospel music. -

PDF of This Issue

Let the RU$h Begin! The Weather Today: unny,76°F(24°C) Tonight: Clear, 54°F (l2°C) Tomorrow: Mostly unny, 82°F (2 ° Details, P ge 2 02139 MIT Living Groups Show Off at Midway /FC Rules Simmons Starts Recruiting One Year Early; Panhellenic Association Takes ore Booths Confuse By Jennifer Krishnan a freshman that the be t thing about NEWS EDITOR it~ons was that "it's got holes in Freshmen The la t Residence Midway of its kind gave the Clas of 2005 a first glimpse at MIT' large array of Pan bel g t mor booth By Shankar Mukherji living options. The Panhellenic Association had ASSOCIATE NEWS EDITOR The Midway, which wa held four booth spaces at thi year' Mid- Residence selection can be a con- last night in Johnson Athletic Cen- way a significant increase from last fu ing and overwhelming process ter, featured all of MIT's FSILG , year, when the five ororities hared for incoming students which i only and every dorm except for Bexley a single booth. compounded by the many rush rules Hall. "In the past, [the Re idence Mid- that govern FSILGs. "It's a little overwhelming, but way] has been more useful to guys," For example, a FSILG member it s exciting at the same time," aid said Panhellenic Vice President of may not speak to a freshman prior Isaac B. Taylor '05. Recruitment Ariya Dararutana '03. to the residence midway. The 200] East Campus' booth featured a "We're hoping to have a larger pres- Interfraternity Council rush rules variety of eccentric costumes, and ence this year." state that 'conversing with freshmen upperc1a smen offered freshmen a Mackenzie L. -

Munger Moss Neon Sign

FACTORY OUTLETS ____ •••~~~ •••••'" I Stop by and visit with the Reid family. The Reids came to this Route 66 location in 1961 and operated the 66 Sunset Lodge as the Capri Motel until 1966. Then in 1972 Shepherd Hills Factory Outlet was born on the same ground as the Capri Motel. Next came the ownership of the Shepherd Hills Motel. In 1999 the Lebanon Route 66 location of the Shepherd Hills Factory Outlet moved into our new modern building. This business' has expanded and now includes eight different locations. ~OCKU 1(1 KNIVES DE BY POTTERY , SWISS ItJ 15.pobell ~Q~~~ pconds & Overstocks, 40% to 50% off Leach Service Serving the motoring public since 1949 9720 Manchester Road Rock Hill, MO 63119 (314) 962-5550 www.Leachservice.com Open 6AM-Midnight Missouri Safety & Emissions Inspections Auto Repairs, Towing, Tires-new & repairs Diesel, bp Gasoline-now with Invigorate, Kerosene Propane Tank Refills 1Qe4aue ~ iu fyt r;<J«'t ~, Ask about our Buy 5 Oil Changes Get One FREElSpecial Full Service Customers, ask about a Free Oil Change punch card. Yes, we still have Full Service where lrien.y attendants pump your gas, clean your windows and check your oil and tires Member Brentwood Chamber 01 Commerce Business Member Route 66 Association SHOW ME ROUTE 66 2 MAG A Z I N E Volume 20, Number 4 - 2010 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE ROUTE 66 ASSOCIATION OF MISSOURI Atures ESTABLISHED JANUARY, 1990 Fe~. 27 Joplin Depot MayHave New Life 3 Officers, Board of Directors, Joe Sonderman FOLLOW THE ASSOCIATION Committees and Associations 29 Diorama Completed for the ONFACEBOOK 4 Editors Notes Lebanon Route 66 Museum Thanks to Carolyn Hasenfratz, Jeep Girl's Journal Jim Thole the Route 66 Association of Carolyn Hasenfratz 31 Warrens Route 66 Lunch Stand Missouri now has a Facebook 5 Membership Matters James H. -

Let Freedom Ring!

Summer 2010 Let Freedom Ring! Barbershopping in Philly by Craig Rigg [The following report is a personal observation and does not reflect the views of the Society or the Illinois District. With luck we’ll face only a few lawsuits.] There’s this moment in the recent barbershop documentary Amer- ican Harmony. Jeff Oxley looks at a monitor as Vocal Spectrum appears on stage during the 2006 quartet contest, singing “Cruella DeVille.” He turns and shakes his head, saying, “The So- ciety’s changing, man.” His sentiments pretty much sum up what the 2010 International Convention and Con- tests at Philadelphia was all about. There’s been a changing of the guard. First, let's take the quartet contest. By now, everybody knows that Storm Front finally got the gold (after much cajoling and trash talk). They are the first comedy oriented quartet since FRED to achieve the pinnacle of quartetting. There’s no doubt these guys can sing; they’re Singing scores put them in second place, bested only by Old School (with Illinois's own Joe Krones at bass). In fact, Old School led after the semi-finals by only 17 points, and OS had won each of the first two rounds. All they had to do was maintain their lead and the gold was theirs. Not to be (a phrase you'll hear again later.) So what did Storm Front do that made the difference? Well, a combination of factors proba- bly did it. First, SF staged one heck of an innovative final set. Their first song, with a bit of mock- ing of Old School and up-and-coming Ringmasters from Sweden, lamented their struggle to reach the top. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

RCA/Legacy Set to Release Elvis Presley - a Boy from Tupelo: the Complete 1953-1955 Recordings on Friday, July 28

RCA/Legacy Set to Release Elvis Presley - A Boy From Tupelo: The Complete 1953-1955 Recordings on Friday, July 28 Most Comprehensive Early Elvis Library Ever Assembled, 3CD (Physical or Digital) Set Includes Every Known Sun Records Master and Outtake, Live Performances, Radio Recordings, Elvis' Self-Financed First Acetates, A Newly Discovered Previously Unreleased Recording and More Deluxe Package Includes 120-page Book Featuring Many Rare Photos & Memorabilia, Detailed Calendar and Essays Tracking Elvis in 1954-1955 A Boy From Tupelo - The Complete 1953-55 Recordings is produced, researched and written by Ernst Mikael Jørgensen. Elvis Presley - A Boy From Tupelo: The Sun Masters To Be Released on 12" Vinyl Single Disc # # # # # Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment, and RCA Records will release Elvis Presley - A Boy From Tupelo - The Complete 1953-1955 Recordings on Friday, July 28. Available as a 3CD deluxe box set and a digital collection, A Boy From Tupelo - The Complete 1953-1955 Recordings is the most comprehensive collection of early Elvis recordings ever assembled, with many tracks becoming available for the first time as part of this package and one performance--a newly discovered recording of "I Forgot To Remember To Forget" (from the Louisiana Hayride, Shreveport, Louisiana, October 29, 1955)--being officially released for the first time ever. A Boy From Tupelo – The Complete 1953-1955 Recordings includes--for the first time in one collection--every known Elvis Presley Sun Records master and outtake, plus the mythical Memphis Recording Service Acetates--"My Happiness"/"That's When Your Heartaches Begin" (recorded July 1953) and "I'll Never Stand in Your Way"/"It Wouldn't Be the Same (Without You)" (recorded January 4, 1954)--the four songs Elvis paid his own money to record before signing with Sun. -

Desert Newsnews

~ The 79th Annual Barbershop Harmony Society’s International Convention ~ 2017 DAILY BULLETIN DESERTDESERT NEWSNEWS Friday July 14th 8 POST CONVENTION 2017 8 Last Minute Articles & Photos From the 2017 BHS Convention in Las Vegas, NV July 3 - 9 Society Honors Grand Central Red Caps Takes Two Steps to Correct Wrong (submitted by Ford Fuller) Grand Central Red Caps Quartet Honored at Saturday Night Spectacular The theme of this year’s Saturday Night Spectacular was “Together, We Sing” featuring the Ambassadors of Harmony & The Vocal Majority mega-chorus, along with quartets Vocal Spectrum and Crossroads. It was an awesome show! This evening’s program is about how our music brings us together. While we cannot erase the errors of the past, we do want to affirm, here and now, that our music is for all, regardless of race, creed or color. We celebrate the spread of our special kind of harmony to more di- verse groups of people, here in America, and throughout the worldwide community, bringing together young and old, rich and poor, black and white. But, perhaps the most poignant moment was a long-overdue correction of a horrible decision made by our Society in 1941. The story be- gins in 1940 when the National SPEBSQSA Convention was held in New York City at which time our society learned of a city-wide Bar- bershop Quartet Competition sponsored by the NYC Parks Department, that actually began in 1935. SPEBSQSA officers decided to invite the winner to the following year’s convention to be held in St. Louis. When the 1941 winner was determined, a telegram was sent to SPEBSQSA letting them know the winner. -

Bob Harbicht the Next Meet Ing News Bits Costa Mesa Couple Has

May 2019 the next meet ing President’s message - Bob Harbicht General Meeting - 7:00 PM, Friday May 31 Do you have a Model A Ford? Live Oak Community Center, 10144 Bogue St. Temple City Does it run? Would you like it to? Does it have some nagging little problem that Program - Our Guest Speaker will be Mr. Ron Mosher, a you haven’t gotten around to fixing member of the the San Fernando A’s. He is a well know in because you’re not sure how to do it? Model A circles and will speak to us about “Model A Stuff!”. Help is available! One of the Sit back and enjoy. benefits of being a member of the Santa Anita A’s is that there are people ready, News Bits willing, and able to help you. The Low End Boys is a group within our club that will Costa Mesa Couple Has Winning Raffle Ticket work with you to get your car running and out on the road. Mickey Fructer (626-797-2048) or [email protected]) heads Hayley and Steven Timmins, a young family residing in up this group. Contact him to discuss your problem. If it’s Costa Mesa California held the winning raffle ticket for the something they can help you with Mickey will set up a time 1929 Model A Ford Roadster restored by the Pasadena High to come to your home and help you fix it. School Model A Ford Club. Drawing of the winning ticket took I spent the morning with the Low End Boys today at place at the Pasadena High School Benefit Concert on April 20��.