Jerry Kang's “Trojan Horses of Race”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STEPHEN MARK, ACE Editor

STEPHEN MARK, ACE Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. DELILAH (series) Various OWN / Warner Bros. Television EP: Craig Wright, Oprah Winfrey, Charles Randolph-Wright NEXT (series) Various Fox / 20th Century Fox Television EP: Manny Coto, Charlie Gogolak, Glenn Ficarra, John Requa SNEAKY PETE (series) Various Amazon / Sony Pictures Television EP: Blake Masters, Bryan Cranston, Jon Avnet, James Degus GREENLEAF (series) Various OWN / Lionsgate Television EP: Oprah Winfrey, Clement Virgo, Craig Wright HELL ON WHEELS (series) Various AMC / Entertainment One Television EP: Mark Richard, John Wirth, Jeremy Gold BLACK SAILS (series) Various Starz / Platinum Dunes EP: Michael Bay, Jonathan Steinberg, Robert Levine, Dan Shotz LEGENDS (pilot)* David Semel TNT / Fox 21 Prod: Howard Gordon, Jonathan Levin, Cyrus Voris, Ethan Reiff DEFIANCE (series) Various Syfy / Universal Cable Productions Prod: Kevin Murphy GAME OF THRONES** (season 2, ep.10) Alan Taylor HBO EP: Devid Benioff, D.B. Weiss BOSS (pilot* + series) Various Starz / Lionsgate Television EP: Farhad Safinia, Gus Van Sant, THE LINE (pilot) Michael Dinner CBS / CBS Television Studios EP: Carl Beverly, Sarah Timberman CANE (series) Various CBS / ABC Studios Prod: Jimmy Smits, Cynthia Cidre, MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION (anthology series) Michael Tolkin ABC / IDT Entertainment Jonathan Frakes Prod: Keith Addis, Sam Egan 3 LBS. (series) Various CBS / The Levinson-Fontana Company Prod: Peter Ocko DEADWOOD (series) Various HBO 2007 ACE Eddie Award Nominee | 2006 ACE Eddie Award Winner Prod: David Milch, Gregg Fienberg, Davis Guggenheim 2005 Emmy Nomination WITHOUT A TRACE (pilot) David Nutter CBS / Warner Bros. Television / Jerry Bruckheimer TV Prod: Jerry Bruckheimer, Hank Steinberg SMALLVILLE (pilot + series) David Nutter (pilot) CW / Warner Bros. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Audio Publishers Association Announces 2018 Audie Award® Finalists in 26 Categories

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Rachel Tarlow Gul Over the River Public Relations 201-503-1321, [email protected] Audio Publishers Association announces 2018 Audie Award® finalists in 26 categories Winners to be honored at the Audies® Gala in New York City on May 31st New York, NY – The Audio Publishers Association (APA) has announced finalists for the 23rd annual Audie Awards® competition, the premier awards program in the United States recognizing distinction in audiobooks and spoken word entertainment. Winners will be revealed at the Audies® Gala on May 31, 2018, at the New-York Historical Society in New York City. “We are excited to announce all of our Audie Awards® finalists for 2018,” says APA President Linda Lee. “It seems that each year the sky is the limit as we see an increase in submissions of incredibly high quality works. This year’s Audies promises to be more exciting than ever as the judges work hard to pick the winners out of such an august field of finalists. We hope to see you there to join in the excitement!” “Audiobook aficionados and industry insiders alike have a heightened excitement about the amazing range of genres and production styles of the finalists and ultimate winners of the Audies,” adds Mary Burkey, Audie Awards® Competition Chair. “Our team of expert judges debating the winner of the Audiobook of the Year award must choose a single audio that combines the very best in narration and production quality with significant sales impact and marketing outreach to be the standard bearer of excellence for the format and audio publishing industry. -

4 Social Cognition

9781405124003_4_004.qxd 10/31/07 2:57 PM Page 66 Social Cognition 4 Louise Pendry KEY CONCEPTS accessibility accountability automatic process categorization continuum model of impression formation controlled process dissociation model encoding goal dependent heuristic inconsistency resolution individuating information outcome dependency priming rebound effect retrieval schema stereotype stereotype suppression 9781405124003_4_004.qxd 10/31/07 2:57 PM Page 67 CHAPTER OUTLINE This chapter introduces the topic of social cognition: the study of how we make sense of others and ourselves. It focuses especially on the distinction between social processes and judgements that are often rapid and automatic, such as categorization and stereotype activation, and those which may require more effort, deliberation and control (for example, stereotype suppression and indi- viduated impression formation). Introduction What is social cognition? What kinds of processes can social cognition research help to explain? We inhabit a hectic social world. In any one day we can expect to deal with many other people. We may meet people for the first time, we may go out with old friends, we may find ourselves in a job interview trying to make a good impression on our prospective employer, queuing in a supermar- ket to pay for groceries, waiting for a train on a busy platform. Even for those of us professing to live ordinary lives, no two days are exactly alike. So, precisely how do we navigate this complex social life? What social information do we attend to, organize, remember and use? These are some of the questions that interest social cognition researchers, and providing answers to them strikes at the very heart of understanding human mental life. -

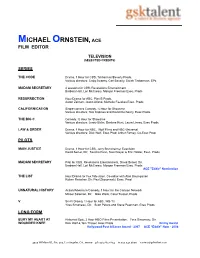

Michael Ornstein,Ace

MICHAEL ORNSTEIN, ACE FILM EDITOR TELEVISION (SELECTED CREDITS) SERIES THE CODE Drama, 1 Hour for CBS, Timberman/Beverly Prods. Various directors; Craig Sweeny, Carl Beverly, Sarah Timberman, EPs MADAM SECRETARY 4 seasons for CBS, Revelations Entertainment Barbara Hall, Lori McCreary, Morgan Freeman Exec. Prods RESURRECTION Hour Drama for ABC, Plan B Prods. Aaron Zelman, Joann Alfano, Michelle Fazekas Exec. Prods CALIFORNICATION Single-camera Comedy, ½ Hour for Showtime Various directors; Tom Kapinos and David Duchovny, Exec Prods. THE BIG C Comedy, ½ Hour for Showtime Various directors; Jenny Bicks, Darlene Hunt, Laura Linney, Exec Prods. LAW & ORDER Drama, 1 Hour for NBC, Wolf Films and NBC-Universal Various directors; Dick Wolf, Exec Prod; Arthur Forney, Co-Exec Prod. PILOTS MAIN JUSTICE Drama, 1 Hour for CBS, Jerry Bruckheimer Television David Semel, Dir; Sascha Penn, Sunil Nayar & Eric Holder, Exec. Prods. MADAM SECRETARY Pilot for CBS, Revelations Entertainment, David Semel, Dir. Barbara Hall, Lori McCreary, Morgan Freeman Exec. Prods ACE "Eddie" Nomination THE LIST Hour Drama for Fox Television, Co-editor with Alan Baumgarten Ruben Fleischer, Dir; Paul Zbyszewski, Exec. Prod. UNNATURAL HISTORY Action/Adventure/Comedy, 1 Hour for the Cartoon Network Mikael Salomon, Dir; Mike Werb, Carol Trussel, Prods. V Sci-Fi Drama, 1 Hour for ABC, WB-TV Yves Simoneau, Dir; Scott Peters and Steve Pearlman, Exec Prods LONG FORM BURY MY HEART AT Historical Epic, 2 Hour HBO Films Presentation, Yves Simoneau, Dir WOUNDED KNEE Dick Wolf & Tom Thayer, Exec Prods Emmy Award Hollywood Post Alliance Award - 2007 ACE “Eddie” Nom - 2008 4929 Wilshire Bl., Ste. 259, Los Angeles, CA., 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] MICHAEL ORNSTEIN, ACE WHO IS CLARK Drama, 2 Hour for Lifetime Television, Sony Pictures TV ROCKEFELLER? Mikael Salomon, Dir; Judith Verno, Ilene Cahn-Powers, Exec Prods. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Fargo: Seeing the Significance of Style in Television Poetics?

Fargo: Seeing the significance of style in television poetics? By Max Sexton and Dominic Lees 6 Keywords: Poetics; Mini-series; Style; Storyworld; Coen brothers; Noah Hawley Abstract This article argues that Fargo as an example of contemporary US television serial drama renews the debate about the links between Televisuality and narrative. In this way, it seeks to demonstrate how visual and audio strategies de-stabilise subjectivities in the show. By indicating the viewing strategies required by Fargo, it is possible to offer a detailed reading of high-end drama as a means of understanding how every fragment of visual detail can be organised into a ‘grand’ aesthetic. Using examples, the article demonstrates how the construction of meaning relies on the formally playful use of tone and texture, which form the locus of engagement, as well as aesthetic value within Fargo. At the same time, Televisuality can be more easily explained and understood as a strategy by writers, directors and producers to construct discourses around increased thematic uncertainty that invites audience interpretation at key moments. In Fargo, such moments will be shown to be a manifestation not only of the industrial strategy of any particular network ‒ its branding ‒ but how is it part of a programme’s formal design. In this way, it is hoped that a system of television poetics ‒ including elements of camera and performance ‒ generates new insight into the construction of individual texts. By addressing television style as significant, it avoids the need to refer to pre-existing but delimiting categories of high-end television drama as examples of small screen art cinema, the megamovie and so on. -

The Semi-Supervised Information Extraction System from HTML: an Improvement in the Wrapper Induction

Knowl Inf Syst DOI 10.1007/s10115-017-1097-2 REGULAR PAPER The BigGrams: the semi-supervised information extraction system from HTML: an improvement in the wrapper induction Marcin Michał Miro´nczuk1 Received: 2 August 2016 / Revised: 2 July 2017 / Accepted: 4 August 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract The aim of this study is to propose an information extraction system, called BigGrams, which is able to retrieve relevant and structural information (relevant phrases, keywords) from semi-structural web pages, i.e. HTML documents. For this purpose, a novel semi-supervised wrappers induction algorithm has been developed and embedded in the BigGrams system. The wrappers induction algorithm utilizes a formal concept analysis to induce information extraction patterns. Also, in this article, the author (1) presents the impact of the configuration of the information extraction system components on information extrac- tion results and (2) tests the boosting mode of this system. Based on empirical research, the author established that the proposed taxonomy of seeds and the HTML tags level analysis, with appropriate pre-processing, improve information extraction results. Also, the boosting mode works well when certain requirements are met, i.e. when well-diversified input data are ensured. Keywords Information extraction · Information extraction system · Wrappers induction · Semi-supervised wrappers induction · Information extraction from HTML 1 Introduction The information extraction (IE) was defined by Moens [48] as the identification, and consequent or concurrent classification and structuring into semantic classes, of specific information found in unstructured data sources, such as natural language text, making infor- mation more suitable for information processing tasks. -

The Role Arabic Literature Can Play to Redress The

READ TO CHANGE: THE ROLE ARABIC LITERATURE CAN PLAY TO REDRESS THE DAMAGE OF STEREOTYPING ARABS IN AMERICAN MEDIA A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mohammed Albalawi May 2016 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published Dissertation written by Mohammed H. Albalawi B.A., King Abdulaziz University, 2001 M.A., King Abdulaziz University, 2010 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Babacar M’Baye , Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Mark Bracher , Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Sarah Rilling Richard Feinberg Ryan Claassen Accepted by Robert Trogdon, Chair, Department of English James L. Blank, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................. v DEDICATION .............................................................................................................................. vi CHAPTERS I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 II. UNDERSTANDING STEREOTYPES ...................................................................... -

Critically-Acclaimed, Award-Winning Original Series That Continue to Make Their Mark on the Cultural Landscape

…critically-acclaimed, award-winning original series that continue to make their mark on the cultural landscape. HOMELAND Who’s the hero – who’s the threat? SHAMELESS It’s summertime and the Gallaghers Golden Globe® winner Claire Danes and Damian Lewis star are cooking up fresh ways to bring home the bacon in a in the suspenseful Showtime Original Series HOMELAND. new season of the Showtime Original Series SHAMELESS When rescued MIA Marine Sgt. Nicholas Brody returns starring William H. Macy and Emmy Rossum. Their ventures home to a hero’s welcome after eight years in torturous may not be moral – or even legal – but they certainly are enemy confinement – volatile CIA officer Carrie Mathison outrageous. While Fiona works and parties at the hottest is convinced he’s a dangerous and determined traitor club in town, Lip, Ian, Debbie, Carl and Liam are getting with terrorist intent. SHOWTIME has ordered season into trouble of their own. And Frank is messing with the two of this award-winning drama series. wrong people. CALIFORNICATION Golden Globe® winner David Duchovny is back in a bangin’ new season of HOUSE OF LIES Don Cheadle and Kristen Bell CALIFORNICATION – and Hank Moody has become are twisting the facts, spinning the numbers and playing hip hop’s most wanted. Rich and powerful rap mogul corporate America for everything they’ve got in the extraordinaire Samurai Apocalypse (Wu-Tang’s RZA) is outrageous new series HOUSE OF LIES. pimped-out famous – and hell bent on getting our bad boy writer into more trouble than he’s ever known. -

Addressing Implicit Bias, Racial Anxiety, and Stereotype Threat in Education and Health Care

Rachel D. Godsil THE SCIENCE OF EQUALITY, VOLUME 1: Seton Hall University School of Law ADDRESSING IMPLICIT Linda R. Tropp University of BIAS, RACIAL ANXIETY, AND Massachusetts Amherst STEREOTYPE THREAT IN UCLA and Harvard Kennedy School of EDUCATION AND HEALTH CARE Government john a. powell University of California, November 2014 Berkeley REPORT AUTHORS Rachel D. Godsil Director of Research, Perception Institute Eleanor Bontecou Professor of Law Seton Hall University School of Law Linda R. Tropp, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences Director, Psychology of Peace and Violence Program University of Massachusetts Amherst President, Center for Policing Equity Associate Professor of Psychology, UCLA Visiting Scholar, Harvard Kennedy School of Government john a. powell Director, Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society Professor of Law, African American and Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley PERCEPTION INSTITUTE Alexis McGill Johnson, Executive Director Rachel D. Godsil, Director of Research Isaac Butler, Senior Editor Research Advisors Joshua Aronson, New York University Matt Barreto, University of Washington DeAngelo Bester, Workers Center for Racial Justice Ludovic Blain, Progressive Era Project Camille Charles, University of Pennsylvania Nilanjana Dasgupta, University of Massachusetts Amherst Rachel D. Godsil, Seton Hall University Law School Jerry Kang, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law john a. powell, University of California, Berkeley L. Song Richardson, University of California, Irvine College of Law Linda R. Tropp, University of Massachusetts Amherst Board of Directors john a. powell, Chair Connie Cagampang Heller Steven Menendian We wish to thank the Ford Foundation, the Open Society Foundation’s Campaign for Black Male Achievement, and the W.K.