Confronting the Unknown: How to Deal with Halakhic Uncertainties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

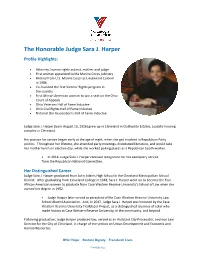

The Honorable Judge Sara J. Harper Profile Highlights

The Honorable Judge Sara J. Harper Profile Highlights: • Attorney, human rights activist, mother and judge • First woman appointed to the Marine Corps judiciary • Retired from U.S. Marine Corps as Lieutenant Colonel in 1986 • Co-founded the first Victims’ Rights program in the country • First African American woman to win a seat on the Ohio Court of Appeals • Ohio Veterans Hall of Fame Inductee • Ohio Civil Rights Hall of Fame Inductee • National Bar Association’s Hall of Fame Inductee Judge Sara J. Harper (born August 10, 1926) grew up in Cleveland in Outhwaite Estates, a public housing complex in Cleveland. Her passion for service began early at the age of eight, when she got involved in Republican Party politics. Throughout her lifetime, she attended party meetings, distributed literature, and would take her mother lunch on election day, while she worked polling places as a Republican booth worker. • In 2014, Judge Sara J. Harper received recognition for her exemplary service from the Republican National Committee. Her Distinguished Career Judge Sara J. Harper graduated from John Adams High School in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District. After graduating from Cleveland College in 1948, Sara J. Harper went on to become the first African-American woman to graduate from Case Western Reserve University’s School of Law when she earned her degree in 1952. • Judge Harper later served as president of the Case Western Reserve University Law School Alumni Association. And, in 2017, Judge Sara J. Harper was honored by the Case Western Reserve University Trailblazer Project, as a distinguished alumnus of color who made history at Case Western Reserve University, in the community, and beyond. -

Hamaspik Central Point

YATED CLASSIFIED ADVERTISEMENTS HELP WANTED Yungerman/Chavrusa To learn with 9th grade bochur during 1st and/or 2nd seder in Monsey Yeshiva. Unique opportunity. Call for details Amazing Opportunity! 845.558.8604 Emet Outreach, a dynamic Kiruv organization located in Help Wanted Queens, NY, Secretary F/T, quickbooks Seeking F/T Office Staff a plus, detail oriented, Administrative Office Clerk YBH OF PASSAIC SEEKS GENERAL STUDIES HEAD TEACHERS: Self-starter, highly organized, • FIRST GRADE GIRLS Coney Island Ave. office. excellent communication skills. • FIFTH GRADE GIRLS Email resume Computer proficient including [email protected] Microsoft Office with Excel, and G Suite. Graphics and website MIDDLE SCHOOL TEACHERS management knowledge is a plus. • 6th GRADE - LANGUAGE ARTS & HISTORY Hours M-Th 10-6, F 9-1. Hours have Teachers • 6th-8th GRADE - MATH some flexibility. Seeking 6th and 7th Grade English Logistics Coordinator Teachers, all subjects, experienced, Motivated, organized individual Yeshiva in Brooklyn Sept. ‘21. Great with positive energy, excellent EARLY CHILDHOOD HEAD TEACHERS: pay, supportive environment. communication and computer skills to • PRE1A (PM) Call 917.921.7280 coordinate and oversee program and • KINDERGARTEN (PM) Email Resume w/ references & experience event logistics. Excellent multitasking [email protected] skills required. 30-40 hrs a week. (some eve hrs required) OTHER POSITIONS AVAILABLE: Kriah/ Early Literacy Opportunity Please email resume & salary requirements • LEARNING CENTER TEACHER-MIDDLE SCHOOL, GENERAL STUDIES SMALL [email protected] GROUP INSTRUCTION (PM HOURS) Ramapo Cheder Preschool seeking Kriah & Literacy in-classroom support staff. • ECD SECRETARY (AM) and ASSISTANTS or text 718.938.0138 Gain Kriah & Literacy proficiency while assisting experienced Moros. -

Report of the Judges of the Court on Managing Transitions in the Judiciary

30 January 2020 Report of the judges of the Court on Managing Transitions in the Judiciary I. Introduction 1. “Transitions”, for purposes of this memorandum, means the process of bringing the service of judges to a close upon the statutory end of their term; as the replacement judges commence their service. 2. A key challenge in the management of transitions in the judiciary is that posed by the end of mandate of one-third of the Court’s judges every three years. This necessitates proper management of the circumstances resulting in the continuation in office of a judge who remains at the Court to complete a trial or appeal in accordance with article 36(10) of the Rome Statute, even though her or his mandate has expired.1 To date, 10 judges have had extensions of mandate under this provision, the duration of which has ranged from several months2 to several years (i.e. between approximately 1.5 – 4 years).3 The present report focuses on this issue. It is an issue the current Presidency has taken up on its own to try and resolve – long before its resonance in aspects of the Draft Non-Paper produced by the Bureau of the ASP. By way of the latter, States Parties have identified the possible need to ‘[d]evelop and implement clear and firm procedures for managing transitions in the judiciary, such as the use of alternate judges, handover strategies etc’.4 1 Article 36(10) provides: ‘Notwithstanding paragraph 9, a judge assigned to a Trial or Appeals Chamber in accordance with article 39 shall continue in office to complete any trial or appeal the hearing of which has already commenced before that Chamber’. -

Chapter 753 Circuit Courts

Updated 2019−20 Wis. Stats. Published and certified under s. 35.18. September 17, 2021. 1 Updated 19−20 Wis. Stats. CIRCUIT COURTS 753.04 CHAPTER 753 CIRCUIT COURTS 753.01 Term of office. 753.077 Preservation of judgments. 753.016 Judicial circuit for Milwaukee County. 753.09 Jury. 753.03 Jurisdiction of circuit courts. 753.10 Attendance of officers, pay; opening court. 753.04 Writs, how issued; certiorari. 753.19 Operating costs; circuit court. 753.05 Seals. 753.22 When court to be held. 753.06 Judicial circuits. 753.23 Night and Saturday sessions. 753.0605 Additional circuit court branches. 753.24 Where court to be held. 753.061 Court; branch; judge. 753.26 Office and records to be kept at county seat. 753.065 Naturalization proceedings, venue. 753.30 Clerk of circuit court; duties, powers. 753.07 Circuit judges; circuit court reporters; assistant reporters; salaries; retire- 753.32 Clerks, etc., not to be appraisers. ment; fringe benefits. 753.34 Circuit court for Menominee and Shawano counties. 753.073 Expenses. 753.35 Rules of practice and trial court administration. 753.075 Reserve judges; service. 753.01 Term of office. The term of office of every elected cir- judges, officers and employees thereof with suitable accommoda- cuit judge is 6 years and until the successor is elected and quali- tions, adequately centralized and consolidated, and with the nec- fied, commencing with the August 1 next succeeding the election. essary furniture and supplies and make provision for its necessary History: 1975 c. 61, 178, 199, 422; 1977 c. 187 s. 92; Stats. -

Loving the Convert Prior to a Completed Conversion: with a Test Case Application of Inviting Conversion Candidates to Pesach Seder and Yom Tov Meals

147 Loving the Convert Prior to a Completed Conversion: With a Test Case Application of Inviting Conversion Candidates to Pesach Seder and Yom Tov Meals By: MICHAEL J. BROYDE and BENJAMIN J. SAMUELS Introduction The Torah enjoins us numerous times concerning the mitzvah of Ahavat ha-Ger,1 which literally means the love of the stranger or sojourner, though is primarily understood in Jewish legal sources to refer more specifically to loving the convert to Judaism.2 Furthermore, the Torah commands us that “you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18), and also charges us to love God (Deuteronomy 6:4), creating multiple duties of love as halakhic obligations. This article will explore the question: When does the duty to love the convert commence and does it impact the con- version process? Does it apply only to a newly converted Jew, or to a Noahide who is in the process of converting, or even to a Gentile who has expressed an interest in converting? The process of conversion to Judaism can be divided into three fun- damental stages: In the first stage, the person makes a personal decision 1 See Leviticus 19:34; Deuteronomy 10:18-19. The Torah also prohibits oppress- ing the convert, “lo toneh” and “Lo tonu”—see Exodus 22:20; Leviticus 19:33; TB Bava Metzia 58b, 59b, and Ben Zion Katz, “Don’t Oppress the Ger,” Seforim Blog <https://seforimblog.com/2019/07/dont-oppress-the-ger/>. However, this article will not investigate the question of when the prohibition against oppressing a convert begins, which may or may not track in parallel with the mitzvah of Ahavat ha-Ger. -

The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha

t HaRofei LeShvurei Leiv: The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Prof. Reuven Kimelman, Advisor Prof. Zvi Zohar, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Ezra Cohen December 2018 Accepted with Highest Honors Copyright by Ezra Cohen Committee Members Name: Prof. Reuven Kimelman Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Lynn Kaye Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Zvi Zohar Signature: ______________________ Table of Contents A Brief Word & Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………... iii Chapter I: Setting the Stage………………………………………………………………………. 1 a. Why This Thesis is Important Right Now………………………………………... 1 b. Defining Key Terms……………………………………………………………… 4 i. Defining Depression……………………………………………………… 5 ii. Defining Halakha…………………………………………………………. 9 c. A Short History of Depression in Halakhic Literature …………………………. 12 Chapter II: The Contemporary Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha…………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 d. Depression & Music Therapy…………………………………………………… 19 e. Depression & Shabbat/Holidays………………………………………………… 28 f. Depression & Abortion…………………………………………………………. 38 g. Depression & Contraception……………………………………………………. 47 h. Depression & Romantic Relationships…………………………………………. 56 i. Depression & Prayer……………………………………………………………. 70 j. Depression & -

Knessia Gedolah Diary

THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN 0021-6615) is published monthly, in this issue ... except July and August, by the Agudath lsrael of Ameri.ca, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y. The Sixth Knessia Gedolah of Agudath Israel . 3 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N.Y. Subscription Knessia Gedolah Diary . 5 $9.00 per year; two years, $17.50, Rabbi Elazar Shach K"ti•?111: The Essence of Kial Yisroel 13 three years, $25.00; outside of the United States, $10.00 per year Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky K"ti•?111: Blessings of "Shalom" 16 Single copy, $1.25 Printed in the U.S.A. What is an Agudist . 17 Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman K"ti•?111: RABBI NISSON WotP!N Editor An Agenda of Restraint and Vigilance . 18 The Vizhnitzer Rebbe K"ti•'i111: Saving Our Children .19 Editorial Board Rabbi Shneur Kotler K"ti•'i111: DR. ERNST BODENHEIMER Chairman The Ability and the Imperative . 21 RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Helping Others Make it, Mordechai Arnon . 27 JOSEPH FRJEDENSON "Hereby Resolved .. Report and Evaluation . 31 RABBI MOSHE SHERER :'-a The Crooked Mirror, Menachem Lubinsky .39 THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not Discovering Eretz Yisroel, Nissan Wolpin .46 assume responsibility for the Kae;hrus of any product or ser Second Looks at the Jewish Scene vice advertised in its pages. Murder in Hebron, Violation in Jerusalem ..... 57 On Singing a Different Tune, Bernard Fryshman .ss FEB., 1980 VOL. XIV, NOS. 6-7 Letters to the Editor . • . 6 7 ___.., _____ -- -· - - The Jewish Observer I February, 1980 3 Expectations ran high, and rightfully so. -

The Vilna Goan and R' Chaim of Volozhin

Great Jewish Books Course The Vilna Goan and R’ Chaim of Volozhin Rabbi Yechezkal Freundlich (גאון ר' אליהו – A. Vilna Goan – R’ Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman Kremer (Gr”a a. 1721 – 1797, born and died in Vilna (capital of Lithuania), which was known at the time as the “Jerusalem of Lita” because of its great Torah scholarship, and he was the undisputed crown jewel. B. Genius amongst geniuses a. Fame as a prodigy began at young age and by early 20s was already recognized as leading Sage in a city of Sages and the address for the most difficult questions b. Photographic memory – though it is said he really had “no memory” because everything was fresh before him as if he just learned it i. Legend: by 4 had memorized all of Tanach. At seven he was taught Talmud by R’ Moses Margalit, by eight, he was studying astronomy during his free time. From the age of ten he continued his studies without the aid of a teacher due to his knowledge already surpassing all his teachers, and by the age of eleven he had committed the entire Talmud to memory. c. Torah study was the supreme value and of paramount importance d. Combined with astounding diligence and dedication to learning Torah i. For at least 40 years (until 70) he never slept more than 2 hours out of 24, and he never slept more than 30 minutes consecutively. ii. Competed the entirety of Torah every 30 days e. Breathtaking range of knowledge. i. there was no subject he did not know intimately: mathematics, astronomy, science, music, philosophy and linguistics. -

The Corona Ushpizin

אושפיזי קורונה THE CORONA USHPIZIN Rabbi Jonathan Schwartz PsyD Congregation Adath Israel of the JEC Elizabeth/Hillside, NJ סוכות תשפא Corona Ushpizin Rabbi Dr Jonathan Schwartz 12 Tishrei 5781 September 30, 2020 משה תקן להם לישראל שיהו שואלים ודורשים בענינו של יום הלכות פסח בפסח הלכות עצרת בעצרת הלכות חג בחג Dear Friends: The Talmud (Megillah 32b) notes that Moshe Rabbeinu established a learning schedule that included both Halachic and Aggadic lessons for each holiday on the holiday itself. Indeed, it is not only the experience of the ceremonies of the Chag that make them exciting. Rather, when we analyze, consider and discuss why we do what we do when we do it, we become more aware of the purposes of the Mitzvos and the holiday and become closer to Hashem in the process. In the days of old, the public shiurim of Yom Tov were a major part of the celebration. The give and take the part of the day for Hashem, it set a tone – חצי לה' enhanced not only the part of the day identified as the half of the day set aside for celebration in eating and enjoyment of a חצי לכם for the other half, the different nature. Meals could be enjoyed where conversation would surround “what the Rabbi spoke about” and expansion on those ideas would be shared and discussed with everyone present, each at his or her own level. Unfortunately, with the difficulties presented by the current COVID-19 pandemic, many might not be able to make it to Shul, many Rabbis might not be able to present the same Derashos and Shiurim to all the different minyanim under their auspices. -

1 I. Introduction: the Following Essay Is Offered to the Dear Reader to Help

I. Introduction: The power point presentation offers a number of specific examples from Jewish Law, Jewish history, Biblical Exegesis, etc. to illustrate research strategies, techniques, and methodologies. The student can better learn how to conduct research using: (1) online catalogs of Judaica, (2) Judaica databases (i.e. Bar Ilan Responsa, Otzar HaHokmah, RAMBI , etc.], (3) digitized archival historical collections of Judaica (i.e. Cairo Geniza, JNUL illuminated Ketuboth, JTSA Wedding poems, etc.), (4) ebooks (i.e. HebrewBooks.org) and eReference Encyclopedias (i.e., Encyclopedia Talmudit via Bar Ilan, EJ, and JE), (5) Judaica websites (e.g., WebShas), (5) and some key print sources. The following essay is offered to the dear reader to help better understand the great gains we make as librarians by entering the online digital age, however at the same time still keeping in mind what we dare not loose in risking to liquidate the importance of our print collections and the types of Jewish learning innately and traditionally associate with the print medium. The paradox of this positioning on the vestibule of the cyber digital information age/revolution is formulated by my allusion to continental philosophies characterization of “The Question Concerning Technology” (Die Frage ueber Teknologie) in the phrase from Holderlin‟s poem, Patmos, cited by Heidegger: Wo die Gefahr ist wachst das Retende Auch!, Where the danger is there is also the saving power. II. Going Digital and Throwing out the print books? Critique of Cushing Academy’s liquidating print sources in the library and going automated totally digital online: Cushing Academy, a New England prep school, is one of the first schools in the country to abandon its books. -

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’Vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 | 17th of Tevet* 2 | 18th of Tevet* New Year’s Day Parashat Vayechi Abraham Moshe Hillel Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech of Dinov Rabbi Salman Mutzfi Rabbi Huna bar Mar Zutra & Rabbi Rabbi Yaakov Krantz Mesharshya bar Pakod Rabbi Moshe Kalfon Ha-Cohen of Jerba 3 | 19th of Tevet * 4* | 20th of Tevet 5 | 21st of Tevet * 6 | 22nd of Tevet* 7 | 23rd of Tevet* 8 | 24th of Tevet* 9 | 25th of Tevet* Parashat Shemot Rabbi Menchachem Mendel Yosef Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon Rabbi Leib Mochiach of Polnoi Rabbi Hillel ben Naphtali Zevi Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi Rabbi Yaakov Abuchatzeira Rabbi Yisrael Dov of Vilednik Rabbi Schulem Moshkovitz Rabbi Naphtali Cohen Miriam Mizrachi Rabbi Shmuel Bornsztain Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler 10 | 26th of Tevet* 11 | 27th of Tevet* 12 | 28th of Tevet* 13* | 29th of Tevet 14* | 1st of Sh’vat 15* | 2nd of Sh’vat 16 | 3rd of Sh’vat* Rosh Chodesh Sh’vat Parashat Vaera Rabbeinu Avraham bar Dovid mi Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch HaRav Yitzhak Kaduri Rabbi Meshulam Zusha of Anipoli Posquires Rabbi Yehoshua Yehuda Leib Diskin Rabbi Menahem Mendel ben Rabbi Shlomo Leib Brevda Rabbi Eliyahu Moshe Panigel Abraham Krochmal Rabbi Aryeh Leib Malin 17* | 4th of Sh’vat 18 | 5th of Sh’vat* 19 | 6th of Sh’vat* 20 | 7th of Sh’vat* 21 | 8th of Sh’vat* 22 | 9th of Sh’vat* 23* | 10th of Sh’vat* Parashat Bo Rabbi Yisrael Abuchatzeirah Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum Rabbi Nathan David Rabinowitz -

Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveichik Rabbi Yechezkel Freundlich

Great Jewish Books Course Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveichik Rabbi Yechezkel Freundlich “Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903-1993) was not only one of the outstanding Talmudists of the twentieth century but also one of its most creative and seminal Jewish thinkers. His stature was such that he was widely known simply as “the Rav” – The Rabbi par excellence. Drawing from a vast reservoir of Jewish and general knowledge, Rabbi Soloveitchik brought Jewish thought and law to bear on the interpretation and assessment of the modern experience. On the one hand, he built bridges between Judaism and the modern world; yet, at the same time, he vigorously upheld the integrity and autonomy of the Jew’s faith commitment.” Dr. David Shatz, Professor of Philosophy, Yeshiva University, Introduction to Lonely Man of Faith Biographical sketch A. Royal Torah Heritage a. born 1903, in Pruzhany (then Russia, next Poland, now Belarus). b. He came from a Rabbinic dynasty dating back some 200 years: His paternal grandfather was Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, and his great-grandfather and namesake was Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, the Beis HaLevi. His great-great- grandfather was Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (The Netziv), and his great- great-great-great grandfather was Rabbi Chaim Volozhin. On his maternal line, he was a grandson of Rabbi Eliyahu Feinstein and his wife Guta Feinstein, née Davidovitch, who, in turn, was a descendant of a long line of Kapulyan rabbis, and of the Tosafot Yom Tov, the Shelah, the Maharshal, and Rashi. c. His father, Rabbi Moshe Soloveichik preceded him as head of the RIETS rabbinical school at Yeshiva University.