Robert Johnson.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May-June 293-WEB

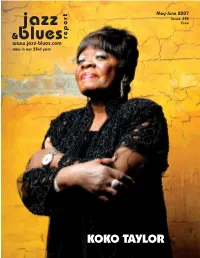

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Eric Clapton

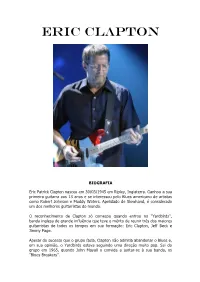

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

Early Blues Bibliography

EARLY BLUES BIBLIOGRAPHY In any selection of books the choice must inevitably be subjective as to what to include or exclude. This selection has ommitted some choices that other might have included. Also there are many articles, periodicals and magazines that provide information for the researcher that cannot be included here but are, perhaps, in Robert Ford's 'Blues Bibliography' or Edward Komara's '100 Books Every Blues Fan Should Have'. This selection is based very much on my own collection of books found in markets, second hand book shops but more recently through Amazon and the web site 'Abe Books' Many books are out of print, have reached the third, fourth or later edition but details are included here that will allow the collector to locate and purchase their own choice. I have not sought to comment on the accuracy, usefulness or expertise of each publication and care should be taken on choice of purchase as many are price inflated when a little more research will lead to better value for money. Where possible I have tended to provide details of hard cover books but many are also available in soft cover at a much reduced price. It should also be remembered that any list such as this is out of date the moment that it is produced. New books are regularly published. The University Presses of America provide a sound source of academic work under the general priciple of 'Publish or Perish' which reflects the wide range of books from the very simple history to the in depth difficult to read study of an aspect of my favourite genre of music - The Blues. -

Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past

The Green Fields of the Mind: Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past Blaine Quincy Waide A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Folklore Program, Department of American Studies Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: William Ferris Robert Cantwell Timothy Marr ©2009 Blaine Quincy Waide ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Blaine Quincy Waide: The Green Fields of the Mind: Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past (Under the direction of William Ferris) This thesis seeks to understand the phenomenon of folk revivalism as it occurred in America during several moments in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. More specifically, I examine how and why often marginalized southern vernacular musicians, especially Mississippi blues singer Robert Johnson, were celebrated during the folk revivals of the 1930s and 1960s as possessing something inherently American, and differentiate these periods of intense interest in the traditional music of the American South from the most recent example of revivalism early in the new millennium. In the process, I suggest the term “disremembering” to elucidate the ways in which the intent of some vernacular traditions, such as blues music, has often been redirected towards a different social or political purpose when communities with divergent needs in a stratified society have convened around a common interest in cultural practice. iii Table of Contents Chapter Introduction: Imagining America in an Iowa Cornfield and at a Mississippi Crossroads…………………………………………………………………………1 I. Discovering America in the Mouth of Jim Crow: Alan Lomax, Robert Johnson, and the Mississippi Paradox…………………………………...23 II. -

The Devil in Robert Johnson: the Progression of the Delta Blues to Rock and Roll by Adam Compagna

The Devil in Robert Johnson: The Progression of the Delta Blues to Rock and Roll by Adam Compagna “I went down to the crossroads, fell down on my knees, I went down to the crossroads, fell down on my knees, Saw the Devil and begged for mercy, help me if you please --- Crearn, “Crossroads” With the emergence of rock and roll in the late nineteen fifties and early nineteen sixties, many different sounds and styles of music were being heard by the popular audience. These early rock musicians blended the current pop style with the non-mainstream rhythm and blues sound that was prevalent mainly in the African-American culture. Later on in the late sixties, especially during the British “invasion,” such bands as the Beatles, Cream, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, and the Yardbirds used this blues style and sound in their music and marketed it to a different generation. This blues music was very important to the evolution of rock and roll, but more importantly, where did this blues influence come from and why was it so important? The answer lies in the Mississippi Delta at the beginning of the twentieth century, down at the crossroads. From this southern section of America many important blues men, including Robert Johnson, got their start in the late nineteen twenties. A man who supposedly sold his soul to the Devil for the ability to play the guitar, Robert Johnson was a main influence on early rock musicians not only for his stylistic guitar playing but also for his poetic lyrics. 1 An important factor in the creation of the genre of the Delta blues is the era that these blues men came from. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 957 SO 020 170 TITLE Folk Recordings

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 957 SO 020 170 TITLE Folk Recordings Selected from the Archive of Folk Culture. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Div. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 59p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; Audiodisks; Audiotape Cassettes; *Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Music; *Songs IDENTIFIERS Bahamas; Black Folk Music; Brazil; *Folk Music; *Folktales; Mexico; Morocco; Puerto Rico; Venezuela ABSTRACT This catalog of sound recordings covers the broad range of folk music and folk tales in the United States, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Morocco. Among the recordings in the catalog are recordings of Afro-Bahain religious songs from Brazil, songs and ballads of the anthracite miners (Pennsylvania), Anglo-American ballads, songs of the Sioux, songs of labor and livelihood, and animal tales told in the Gullah dialect (Georgia). A total of 83 items are offered for sale and information on current sound formats and availability is included. (PPB) Reproductions supplied by EMS are the best that can be made from the original document. SELECTED FROM THE ARCHIVE OF FOLK CULTURE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON. D.C. 20540 U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER IERICI hisdocument has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it C Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction duality Pointsof view or opinions stated in thisdccu- ment do not necessarily represent officral OERI motion or policy AM. -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

BLUES UNLIMITED Number Four (August 1963)

BLUES UN LI Ml TED THE JOURNAL OF “THE BLUES APPRECIATION SOCIETY” EDITED BY SIMON A. NAPIER - Jiiiiffiber Four August 196^ ; purposes of ^'HLues Unlimited* &re several-fold* To find out more about tlse singers is : §1? iiaportant one* T® document th e ir records . equally so,, This applies part!cularly with .postwar "blues ' slmgers and labels. Joho Godrieh m d Boh Dixon ? with the Concert ed help> o f many collectors? record companies imd researchers* .^aTe/v.niide^fHitpastri'Q. p|»©gr;e8Sv, In to l i ‘s.ting. the blues records made ■ parlor to World War IXa fn a comparatively short while 3 - ’with & great deal of effort,.they have brought the esad of hlues discog raphy prewar- in sights Their book?. soon t® be published, w ill be the E?5?st valuable aid. 't o blues lovers yet compiled,, Discography of-;p©:stw£sr ...artists....Is,.In.-■■. a fa r less advanced state* The m&gasine MBlues Research1^ is doing. amagni fieezst- ^ob with : postwar blues;l^bei:s:^j Severd dis^grg^hers are active lis tin g the artists' work* We are publishing Bear-complete discographies xb the hope that you3 the readers^ w ill f i l l In the gaps* A very small proportion o f you &re: helping us in this way0 The Junior Farmer dis&Oc.: in 1 is mow virtu ally complete« Eat sursiy . :s®eb®ciy,:h&s; Bake^;31^;^: 33p? 3^o :dr3SX* Is i t you? We h&veii#t tie&rd from y<&ia£ Simil^Xy: ^heM. -

Robert Johnson from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Robert Johnson From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Background information Birth name Robert Leroy Johnson Born May 8, 1911 Hazlehurst, Mississippi Died August 16, 1938 (aged 27) Greenwood, Mississippi Genres Delta blues Occupation(s) Musician, songwriter Instruments Guitar, vocals, harmonica Years active 1929 – 1938 Notable instruments Gibson L-1 Robert Leroy Johnson (May 8, 1911 – August 16, 1938) was an American singer-songwriter and musician. His landmark recordings in 1936 and 1937, display a combination of singing, guitar skills, and songwriting talent that has influenced later generations of musicians. Johnson's shadowy, poorly documented life and death at age 27 have given rise to much legend, including the Faustian myth that he sold his soul at a crossroads to achieve success. As an itinerant performer who played mostly on street corners, in juke joints, and at Saturday night dances, Johnson had little commercial success or public recognition in his lifetime. It was only after the reissue of his recordings in 1961, on the LP King of the Delta Blues Singers that his work reached a wider audience. Johnson is now recognized as a master of the blues, particularly of the Mississippi Delta blues style. He is credited by many rock musicians as an important influence; Eric Clapton has called Johnson "the most important blues singer that ever lived." Johnson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an early Influence in their first induction ceremony in 1986. In 2010, David Fricke ranked Johnson fifth in Rolling Stone′s list of the 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time. Life and career Early life Robert Johnson was born in Hazlehurst, Mississippi possibly on May 8, 1911, to Julia Major Dodds (born October 1874) and Noah Johnson (born December 1884). -

Open the Blues Is a Healer

! at life – can’t hide what is in my face. How will it end, ain’t got a " iend, My only sin, is in my skin, What did I do to be so black and blue?” Armstrong’s celebrity stance as an entertainer caused rejection to later generations of African Americans who saw remnants of “Uncle Tomism”. However, this overlooks the struggles and strategising he used to gain acceptance across the racial divide. Likewise bluesman Sam Chatman’s lyrics: “Say God made us all; he made some at night, ! at’s why he didn’t take time to make us all white. I’m bound to change my name I have to paint my face, So I won’t be kin to that Ethiopian race.” The Presley Holy Shrine, Graceland " ese may be taken as irony or painful declamation. Either way, they had no I was searching out the location of the my understanding. However, they never resonance with black empowerment which, roots of this compelling music. I wanted quite got inside my skin to reach whatever in order to free itself from the victimised to pay homage to the heroes and heroines it is we call ‘soul’ in the way that these voices of oppression, tended to je% ison the from my adolescence that helped in! uence bluesmen and women did. By contrast, blues as part of that new consciousness, too. and sustain me in my encounters with many were barely educated, all black; all However, it remains true that this life, personally and professionally. " ese raised in deep poverty, grotesque social music has a near magical power to speak mentors and their work o# en raised me disadvantage and race discrimination, to the darker emotions about the pain of from the depths of my own occasional yet spoke to my condition, so unlike rejection, discrimination, disappointment, depressions, troubles and sorrows, and theirs in background. -

Rock the Blues Away

ROCK THESE BLUES AWAY. The Recordings of John Lee Hooker since 1981 ROCK THESE BLUES AWAY The Recordings Of John Lee Hooker Since 1981 By Gary Hearn (Feb. 2006) Introduction In 1992 Les Fancout’s sessionography of John Lee Hooker – “Boogie Chillen” – was published in booklet form by Blues & Rhythm magazine (ed. Tony Burke). This pamphlet is intended to update Les’ work with all the known Hooker sessions since 1981. Though details on other, earlier, sessions have come to light through recent releases, I have excluded them from the scope of my research and it is left to others to publish those corrections and additions elsewhere. The recordings listed here come from the final phase of John’s career during what is known as the Rosebud era, the name of his management company. To my imperfect mind, the best – and darkest – of them found release on the “Boom Boom” album put out by Pointblank in 1993. This was also a period when blues artists were called upon to provide benevolent cameos to artists better known in the mainstream. John took part in many such sessions with varying degrees of success; whatever the finished product, his contributions were immediately recognisable. The compact discs in this survey are, as far as I can tell, the first UK issue shown listed in order of catalogue number for ease of cross-reference to the sessionography. Because record companies re-issue, re-package and licence their recordings, subsequent issues are not considered. None of the cd-singles listed are still available and are shown merely in evidence of the penetration of the “John Lee Hooker” brand. -

Zur Deutschen Übersetzung...15 Lavere

Inhalt Vorwort des Herausgebers zur deutschen Übersetzung......................15 Vorwort von Stephen C. LaVere........................................................17 Vorwort des Autors........................................................................... 20 Danksagungen................................................................................... 23 Einführung......................................................................................... 26 Robert Johnson - Biographie.............................................................37 Die frühen Jahre des Robert Johnson............................................ 37 Robert Johnson als junger Mann................................................... 42 Die Wanderjahre des Musikers...................................................... 46 Die Aufnahmejahre.........................................................................56 Der Tod von Robert Johnson......................................................... 66 Robert Johnson - Mythos, Einfluss, Bedeutung und Erbe................ 75 Die Legende von Crossroads......................................................... 75 John Hammond lässt Robert Johnson auferstehen......................... 82 Eine neues Publikum..................................................................... 90 Robert Johnson wird ein globales Phänomen................................ 96 Der Film, der die Legende veränderte..........................................108 Die Fehde über die Fotos Robert Johnsons..................................111 Die