Memoirs of the Duke De Saint-Simon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DU CENTRE Et La France, Sauf Les Sept Départements R

NEUVIEME ANNEE. - H» 155 VINQT-CINQ CENTIMES ONNEMENTS AB âdmînlstratîoo et Rédactioni 7 2fr. 9, PlAtt PeafâiNS-OEï-BASRSfc 9 LIMOGES 27.21 Téléphone.. | 27" POPULAIRE 22 PUBLICITÉ , h Hgn» 3 fr. ADRESSE TÉLÉGRAPHIQUE t La Publicité pour la région i " ,, — 4 fr. La Publicité pour la région parisienne " — 8 fr. Haute-Vienne. Creuse, Corrèze, Dordogne, NALPOPUL, LIMOGES locale Charente Vienne, Indre DU CENTRE et la France, sauf les sept départements R. C Limoge* 1814 est reçue aux bureaux du journal, nHiiiiniuuiiiiiiiiHiiMliiiiiiiui^uiiriiiiiiiiiMiiiiiiiiMiiiiiniMiiniiiiiiniHliiiiiiiniiniiinniiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiniilli: du Centre, est reçue : . popolaire têt dtêtgni Bureaux du POPULAIRE DD CENTRE, à PARIS, iiZ*,tio» </« etmonctê ludictairté 9. Place Fontaine-des-Barres • LIMOGES Compte courant postal » ■ r*" ,i légales Journal Quotidien Régional 5, Rue Saint-Augustin. Chèques Postauj : limoges 107 «s» Téléphone: 27-21. 27-22 Organe do Socialisme Téléphone : Richelieu 69-00 Trois lignes groupées. LIMOGES 107 de la République et de la Démocratie La Conférence du Désarmement CONSEIL DE CABINET La crise ministérielle belge LES NEGOCIATIONS COMMERCIALES UNE HISTOIRE EXTRAORDINAIRE DUMPING JAPONAIS FRANCO-BRITANNIQUES LES MACHINES japonais sont, dès à présent, obligés de Barthou UN EXPOSE LA COMPOSITION UN ACCORD Les A CALCULER compter avec les réactions économiques du nouveau ministère des autres nations. est de retour SUR LES TRAVAUX SEMBLE PROCHAIN des Assurances SIX MINISTRES CONSERVENT LE CONTINGENTEMENT Sociales VANDERVELDE à Paris DE GENEVE LEUR PORTEFEUILLE DES SOIERIES Emile Bruxelles, 9 juin. LE MINISTRE DU TRAVAIL DIVERSES PERSONNALITES M. DOUMERGUE Suivant le Malin, sauf imprévu, la Londres, 0 juin. TRANSMET LE DOSSIER AU GARD8 est difficile, par le re que cinq. D'où avantage tempo- L'ACCOMPAGNAIENT DES SCEAUX OSIBIEN AU NOM DU CABINET, FELICITE nouvelle combinaison ministérielle se . -

Jeanne D'albret Was the Most Illustrious Woman of Her Time, and Perhaps One of the Most Illustrious Women in All History

Jeanne D’Albret (1528 – 1572) Jeanne d'Albret was the most illustrious woman of her time, and perhaps one of the most illustrious women in all history. She was the only daughter of Margaret of Valois, Queen of Navarre (and sister of King Francois 1st), whose genius Jeanne inherited, and whom she surpassed in her gifts of governing, and in her more consistent attachment to the Reformation. Her first husband Germany’s Duke of Cleves, to whom she was forced to wed at the age of 12 in 1541, no more consummated the marriage than placing his foot in her bed. Her fine intellect, elevated soul, and deep piety were unequally yoked with Anthony de Bourbon, her second husband in 1549, a man of humane dispositions, but of low tastes, indolent habits, and of paltry character. His marriage with Jeanne d'Albret brought him the title of King of Arragon, whose usurpation was confirmed by Pope Julius II, so King of Navarre; but his wife was a woman of too much sense, and her dominions were restricted to that portion of the ancient Navarre cherished too enlightened a regard for the welfare of her subjects, to which lay on the French side of the Pyrenees. give him more than the title. She took care not to entrust him with the reins of government. "Unstable as water," he spent his life in traveling In 1560, we have said, Jeanne d'Albret made open profession of the between the two camps, the Protestant and the Popish, unable long Protestant faith. In 1563 came her famous edict, dated from her to adhere to either, and heartily despised by both. -

Historical Calendars, Commemorative Processions and the Recollection of the Wars of Religion During the Ancien Régime

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library © The Author 2008. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for the Study of French History. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected] doi:10.1093/fh/crn046, available online at www.fh.oxfordjournals.org Advance Access published on October 8, 2008 DIVIDED MEMORIES? HISTORICAL CALENDARS, COMMEMORATIVE PROCESSIONS AND THE RECOLLECTION OF THE WARS OF RELIGION DURING THE ANCIEN RÉGIME PHILIP BENEDICT * Abstract — In the centuries that followed the Edict of Nantes, a number of texts and rituals preserved partisan historical recollections of episodes from the Wars of Religion. One important Huguenot ‘ site of memory ’ was the historical calendar. The calendars published between 1590 and 1685 displayed a particular concern with the Wars of Religion, recalling events that illustrated Protestant victimization and Catholic sedition. One important Catholic site of memory was the commemorative procession. Ten or more cities staged annual processions throughout the ancien régime thanking God for delivering them from the violent, sacrilegious Huguenots during the civil wars. If, shortly after the Fronde, you happened to purchase at the temple of Charenton a 1652 edition of the Psalms of David published by Pierre Des-Hayes, you also received at the front of the book a twelve-page historical calendar listing 127 noteworthy events that took place on selected days of the year. 1 Seven of the entries in this calendar came from sacred history and told you such dates as when the tablets of the Law were handed down on Mount Sinai (5 June) or when John the Baptist received the ambassador sent from Jerusalem mentioned in John 1.19 (1 January). -

Publication DILA

o Quarante-septième année. – N 28 A ISSN 0298-296X Vendredi 8 février 2013 BODACCBULLETIN OFFICIEL DES ANNONCES CIVILES ET COMMERCIALES ANNEXÉ AU JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE DIRECTION DE L’INFORMATION Standard......................................... 01-40-58-75-00 LÉGALE ET ADMINISTRATIVE Annonces....................................... 01-40-58-77-56 Accueil commercial....................... 01-40-15-70-10 26, rue Desaix, 75727 PARIS CEDEX 15 Abonnements................................. 01-40-15-67-77 www.dila.premier-ministre.gouv.fr (9 h à 12 h 30) www.bodacc.fr Télécopie........................................ 01-40-58-77-57 BODACC “A” Ventes et cessions - Créations d’établissements Procédures collectives Procédures de rétablissement personnel Avis relatifs aux successions Avis aux lecteurs Les autres catégories d’insertions sont publiées dans deux autres éditions séparées selon la répartition suivante Modifications diverses........................................ BODACC “B” Radiations ............................................................ } Avis de dépôt des comptes des sociétés ....... BODACC “C” Banque de données BODACC servie par les sociétés : Altares-D&B, EDD, Extelia, Questel, Tessi Informatique, Jurismedia, Pouey International, Scores et Décisions, Les Echos, Creditsafe, Coface services, Cartegie, La Base Marketing,Infolegale, France Telecom Orange, Telino et Maxisoft. Conformément à l’article 4 de l’arrêté du 17 mai 1984 relatif à la constitution et à la commercialisation d’une banque de données télématique des informations contenues dans le BODACC, le droit d’accès prévu par la loi no 78-17 du 6 janvier 1978 s’exerce auprès de la Direction de l’information légale et administrative. Le numéro : 3,65 € Abonnement. − Un an (arrêté du 11 décembre 2012 publié au Journal officiel du 13 décembre 2012) : France : 448,60 €. -

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans - Wikipedia

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Philippe_II,_Duke_of_Orléans Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans Louis Philippe Joseph d'Orléans (13 April 1747 – 6 November 1793), commonly known as Louis Philippe Joseph Philippe, was a major French noble who supported the French Revolution. d'Orléans He was born at the Château de Saint-Cloud. He received the title of Duke of Montpensier at birth, then that of Duke of Chartres at the death of his grandfather, Louis d'Orléans, in 1752. At the death of his father, Louis Philippe d'Orléans, in 1785, he inherited the title of Duke of Orléans and also became the Premier prince du sang, title attributed to the Prince of the Blood closest to the throne after the Sons and Grandsons of France. He was addressed as Son Altesse Sérénissime (S.A.S.). In 1792, during the Revolution, he changed his name to Philippe Égalité. Louis Philippe d'Orléans was a cousin of Louis XVI and one of the wealthiest men in France. He actively supported the Revolution of 1789, and was a strong advocate for the elimination of the present absolute monarchy in favor of a constitutional monarchy. He voted for the death of King Louis XVI; however, he was himself guillotined in November 1793 during the Reign of Terror. His son Louis Philippe d'Orléans became King of the French after the July Revolution of 1830. After him, the term Orléanist came to be attached to the movement in France that favored a constitutional monarchy. Contents Early life Duke of Orléans Succession First Prince of the -

Périgord FREE 2017 - 2018 Www Périgord Best Of

2017 2018 2017 - 2018 English edition best of FREE Digital version périgord best of périgord www.petitfute.com PERIGORD NOIR Live each moment at terrasson lavilledieu ge Ho Herita use Sa in t S o if u l r c c s h a u p l r c a h M t n V 2017 u s i l Nouveau a l r e r bateau! e ja r T d e in rr s a ab G Cluzeaux Les Jardins de l’Imaginaire Tourist office of Vézère Périgord Noir rue Jean Rouby - 24120 TERRASSON LAVILLEDIEU Tél. : +33 5 53 50 37 56 www.ville-terrasson.fr 504925_2C.indd 1 4/3/17 9:49 AM PUBLISHING Collection Directors and authors : Dominique AUZIAS et Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE Welcome to Publishing manager : Cécilia DELACOURT In collaboration with Didier MENDUNI périgord! Authors : Claire DELBOS, Sandrine ANSEL LEMASSON, Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS et alter Publishing director : Stéphan SZEREMETA Publishing team (France) : Elisabeth COL, Maurane CHEVALIER, Silvia FOLIGNO, Tony DE SOUSA Made for English-speaking people looking for good tips Publishing team (World) : Patrick MARINGE, Caroline MICHELOT, Morgane VESLIN, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET, and addresses in Périgord, “Best of Périgord” by Petit Futé Talatah FAVREAU, Hector BARON is an essential how-to guide to find an accommodation, a STUDIO Studio Manager : Sophie LECHERTIER restaurant, to organize your visits and outings and ensure a assisted by Romain AUDREN pleasant stay in this beautiful land! Périgord is well known Layout : Julie BORDES, Élodie CLAVIER, Sandrine MECKING, Delphine PAGANO, Laurie PILLOIS, Sara DOLLE, by all lovers of gastronomy and historical sites. -

Courtiers and Favourites of Royalty

'#. ^--V*! Presented to the m LIBRARY ofthe \\\ UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO VICTORIA COLLEGE LIBRARY "W (Courtiers and uvountes a V'.J^y ^^:sm-L-A \ {Memoirs of the Court of France Wiîh Contemporary and (Modem Illustrations Colleded from the French [^Q.itiofia! ^^^rchives Léon Vallée UBRARIAN AT THE BIBLIOTHEQUE NATION Al F Madame Sophie ÊKà«f hVg. ilercier. Park Soaeie des ^btbiwpnues New York {Menill &- ^aker iMx aiiiqOi^ dmfifafiM f Courtiers and Favourites of T{qyalty (Memoirs of the Court of France IVith Contemporary and {Modem Illustrations CoUeâfed from the French U^ational ^Archives BY Léon Vallée LIBRARIAN AT THE BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE (Memoirs of "'Duke de T^ichelieu In Three Volumes Vol. II Paris Société des 'Bibliophiles New York (Merrill & ^Baker — EDITION "DU "PETIT TRIANON Ltmitea to One Tnousana Sets >'» U4^ .snuriJaa .M o1 uailarloiH ab eiuQ sdi lo leliôJ arit J?.niÊ§Ê anoiïÊiaqo oJ gniitabi Letter of the Duke de Richelieu to M. Betliune, referring to opérations against the King of Prussia I I i i 5 ^ LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS VOLUME II Madame Sophie. Frontispiece pagb Baron de Montesquieu ......... 16 In thb Time of the Regency . .20 Louis XV at the Time of His Accession to the Throne of France 24 The Duchess Mazabin 96 The Royal Hunt 134 Louis XIV and La Valllère 262 The King's Favourite 308 Marie Leczinska, Wife of Louis XV 334 MEMOIRS OF MARSHAL DUKE DE RICHELIEU BY M. F, BARRIERE — T able of Contents. VOLUME II. CHAPTER XXXVII. The Sulpicians wish to deprive parliament of ail knowlege of ec- clesiastical affairs.—The address of Abbé Pucelle.—Parlia- ment goes to Marly and is not received.—The exclamations of Cardinal de Fleury. -

Ambassadors to and from England

p.1: Prominent Foreigners. p.25: French hostages in England, 1559-1564. p.26: Other Foreigners in England. p.30: Refugees in England. p.33-85: Ambassadors to and from England. Prominent Foreigners. Principal suitors to the Queen: Archduke Charles of Austria: see ‘Emperors, Holy Roman’. France: King Charles IX; Henri, Duke of Anjou; François, Duke of Alençon. Sweden: King Eric XIV. Notable visitors to England: from Bohemia: Baron Waldstein (1600). from Denmark: Duke of Holstein (1560). from France: Duke of Alençon (1579, 1581-1582); Prince of Condé (1580); Duke of Biron (1601); Duke of Nevers (1602). from Germany: Duke Casimir (1579); Count Mompelgart (1592); Duke of Bavaria (1600); Duke of Stettin (1602). from Italy: Giordano Bruno (1583-1585); Orsino, Duke of Bracciano (1601). from Poland: Count Alasco (1583). from Portugal: Don Antonio, former King (1581, Refugee: 1585-1593). from Sweden: John Duke of Finland (1559-1560); Princess Cecilia (1565-1566). Bohemia; Denmark; Emperors, Holy Roman; France; Germans; Italians; Low Countries; Navarre; Papal State; Poland; Portugal; Russia; Savoy; Spain; Sweden; Transylvania; Turkey. Bohemia. Slavata, Baron Michael: 1576 April 26: in England, Philip Sidney’s friend; May 1: to leave. Slavata, Baron William (1572-1652): 1598 Aug 21: arrived in London with Paul Hentzner; Aug 27: at court; Sept 12: left for France. Waldstein, Baron (1581-1623): 1600 June 20: arrived, in London, sightseeing; June 29: met Queen at Greenwich Palace; June 30: his travels; July 16: in London; July 25: left for France. Also quoted: 1599 Aug 16; Beddington. Denmark. King Christian III (1503-1 Jan 1559): 1559 April 6: Queen Dorothy, widow, exchanged condolences with Elizabeth. -

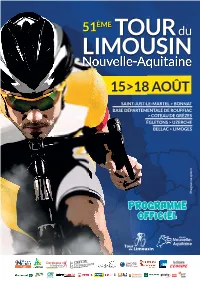

Programme Officiel

Programme gratuit PProgrammerogramme OOfficielfficiel Partenaire du Le mot du président 51e édition du Tour du Limousin… Comme les précédentes, cette édition se doit d’être de très haut-niveau. Passée la 50e, le Tour du Limousin devait se préparer à quelques changements. La première modifi cation étant de coller à l’actualité et de faire évoluer son appel- lation. Aussi, la dernière Assemblée Générale prenait l’option de ra- jouter le nom de sa nouvelle région à son nom originel, pour devenir le Tour du Limousin - Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Une évolution également liée à la mise en place d’un partenariat avec le Conseil Départemental de la Dordogne, un département riche d’un patrimoine culturel et his- torique de premier plan, où le cyclisme a toujours occupé une place importante sur le plan sportif. Autre nouveauté, le décalage de l’étape fi nale du vendredi au samedi (avec un départ le mercredi) afi n de permettre au plus grand nombre d’assister à l’arrivée sur le boulevard de Beaublanc à Limoges. Enfi n, dernière évolution et non des moindres, suite aux démarches entre- prises depuis environ deux ans avec la Chaîne l’Équipe, les deux der- nières heures de chaque étape seront retransmises en direct. Des images de notre belle région vont être véhiculées dans la France entière. Le Tour du Limousin - Nouvelle-Aquitaine franchit un nouveau cap, inespéré il y a encore quelques années. Un travail de longue haleine qui aujourd’hui porte ses fruits. Il continuera également, comme lors des éditions précédentes, d’être un acteur majeur de l’animation du territoire. -

Engravings, Etchings, Mezzotinits, Lithographs, and Acquatints, M0871

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8fr010j No online items Guide to the Leon Kolb collection of Portraits: engravings, etchings, mezzotinits, lithographs, and acquatints, M0871 Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Processed by Special Collections staff. Stanford University. Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, California, 94305-6064 Repository email: [email protected] 2010-09-16 M0871 1 Title: Leon Kolb, collector. Portraits: engravings, etchings, mezzotinits, lithographs, and acquatints Identifier/Call Number: M0871 Contributing Institution: Stanford University. Department of Special Collections and University Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 9.0 Linear feet Date (inclusive): ca. 1600-1800 Abstract: The subjects include rulers, statesmen, authors, scholars and other famous personages from ancient times to the nineteenth century. Most of the prints were produced in the 17th and 18th centuries from paintings by Has Holbein, Anthony Vandyke, Godfrey Kneller, Peter Lely and other noted artists. Processing Information Note Item level description for items in Series 1 was taken from printed catalogue: Portraits: a catalog of the engravings, etchings, mezzotints, and lithographs presented to the Stanford University Library by Dr. and Mrs. Leon Kolb . Compiled by Lenkey, Susan V., [Stanford, Calif.] Stanford University, 1972. Collection Scope and Content Summary Arranged by name of subject, each print in Series 1 is numbered for convenient reference in the various indices in the printed catalogue by Susan Lenkey. Painters and engravers, printing techniques and social and historical positions of the subjects are identified and indexed as well.The subjects include rulers, statesmen, authors, scholars and other famous personages from ancient times to the nineteenth century. -

Périgord Noir

LA VERSION COMPLETE DE VOTRE GUIDE BEST OF PERIGORD 2014 en numérique ou en papier en 3 clics à partir de 4.49€ Disponible sur EDITION Collection Directors and Authors: Dominique AUZIAS et Jean Paul LABOURDETTE Welcome Responsibles for Publishing: Didier MENDUNI and Cécilia DELACOURT assisted by Cécilia DELACOURT, Didier MENDUNI Authors: Claire DELBOS, Sandrine ANSEL LEMASSON, to Périgord! Jean Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS, Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS et alter Publishing Director: Stéphan SZEREMETA Publishing Team: François TOURNIE, Jeff BUCHE, Grégoire DECONIHOUT, Perrine GALAZKA Rédaction Monde : Patrick MARINGE, Caroline MICHELOT, Morgane VESLIN, Julien BERNARD, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET ade for English-speaking people looking for STUDIO M good tips and good addresses in Périgord, “Best Studio Manager: Sophie LECHERTIER of Périgord” by Petit Futé is an essential how-to assisted by Romain AUDREN guide to find an accommodation, a restaurant, to organize Layout: Julie BORDES, Élodie CLAVIER, Sandrine MECKING, Delphine PAGANO, Laurie PILLOIS et Hugues RENAULT your visits and outings to be sure you will enjoy your stay Pictures Management And Mapping: Robin BEDDAR in this beautiful land! WEB It is true that Périgord is well known by all lovers of Web Technical Director: Lionel CAZAUMAYOU Web Management And Development: Jean-Marc gastronomy and historical sites. Périgord is a land with REYMUND assisté de Florian FAZER, Anthony GUYOT, Cédric great patrimonial weath and countless attractions: castles, MAILLOUX, Christophe PERREAU abbeys, churches, bastides, trogloyctic sites, caves, chasms, PUBLICITY TEAM gardens, museums, theme parks, etc. Web And Sales Director: Olivier AZPIROZ Local Publicity Responsible: Michel GRANSEIGNE Assistant: Victor CORREIA Périgord is divided into four touristic regions, a classification Customer Relationship Management: Vimla MEETTOO respected in this guide. -

Displays of Medici Wealth and Authority: the Acts of the Apostles and Valois Fêtes Tapestry Cycles

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Displays of Medici Wealth and Authority: The Acts of the Apostles and Valois Fêtes Tapestry Cycles Madison L. Clyburn University of Central Florida Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Clyburn, Madison L., "Displays of Medici Wealth and Authority: The Acts of the Apostles and Valois Fêtes Tapestry Cycles" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 523. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/523 DISPLAYS OF MEDICI WEALTH AND AUTHORITY: THE ACTS OF THE APOSTLES AND VALOIS FÊTES TAPESTRY CYCLES by MADISON LAYNE CLYBURN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Art History in the College of Arts & Humanities and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2019 Thesis Chair: Margaret Ann Zaho, Ph.D. © 2019 Madison Layne Clyburn ii ABSTRACT The objective of my research is to explore Medici extravagance, power, and wealth through the multifaceted artistic form of tapestries vis-à-vis two particular tapestry cycles; the Acts of the Apostles and the Valois Fêtes. The cycles were commissioned by Pope Leo X (1475- 1521), the first Medici pope, and Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589), queen, queen regent, and queen mother of France.