Policing Intensity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Badan Berkanun Badan Berkanun

BADAN BERKANUN 1. AKADEMI PERCUKAIAN MALAYSIA Lembaga Hasil Dalam Negeri Persiaran Wawasan 43650 Bandar Baru Bangi Selangor (u.p : Encik Rusdi Husain) Tel : 03-89201973 2. Balai Seni Lukis Negara Perpustakaan No. 2, Jalan Temerloh Off Jalan Tun Razak 53200 Kuala Lumpur (u.p. : Yong Zalifah binti Ibrahim) Tel. : 016-6116576 Faks : 03-40254987 E-mail : [email protected] 3. BANK NEGARA MALAYSIA Unit Perpustakaan & Arkib Jalan Dato Onn 50480 Kuala Lumpur Tel : 03-26907326 Faks : 03-26912990 E-mel : [email protected] 4. BANK PERTANIAN MALAYSIA Lebuh Pasar Besar Peti Surat 10815 50726 Kuala Lumpur (u.p : En. Hazmy Hashim) Tel : 03-26922033 Faks : 03-26914908 5 DEWAN BAHASA DAN PUSTAKA Pusat Dokumentasi Melayu Peti Surat 10803, Jalan Wisma Putera 50926 Kuala Lumpur (u.p : Puan Kamariah Abu Samah) Tel : 03-21483548/1037 Faks : 03-21442081 1 E-mel : [email protected] URL : http://dbp.gov.my 6. INSTITUT KESELAMATAN & KESIHATAN PEKERJA NEGARA (NIOSH) Lot 1, Jalan 15/1 Seksyen 15 43600 Bandar Baru Bangi (u.p : En Sharir Adenan) Tel : 03-89261900 Faks : 03-89262900 7. INSTITUT LATIHAN KESELAMATAN SOSIAL KWSP (ESSET) Batu 18 ½ , Sungai Tangkas Jalan Bangi 43000 Kajang Selangor (u.p : Wan Izani Wan Rawi) Tel : 03-89251900 Faks : 03-89265100 8. INSTITUT PENYELIDIKAN DAN KEMAJUAN PERTANIAN MALAYSIA (MARDI) Perpustakaan Pusat Peti Surat 12301, Pejabat Pos Besar 50774 Kuala Lumpur (u.p : Puan Khadijah Ibrahim) Tel : 03-89437111 Faks : 03-90483664/90426434 E-mel : [email protected] 9. INSTITUT PIAWAIAN DAN PENYELIDIKAN MALAYSIA (SIRIM) Sirim Berhad Unit Sumber Informasi No.1, Persiaran Dato’ Menteri Peti Surat 7035, Seksyen 2 40911 Shah Alam Selangor (u.p : Puan Jamayah Basiron) Tel : 03-5446000/5446117 Faks : 03-55167114 2 10. -

2. Penjenamaan

Jurnal Komunikasi Borneo 2014 vol 1 PENJENAMAAN RTM : Kajian Radio RTM Sabah Mahat Jamal Program Komunikasi, Sekolah Sains Sosial, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Penjenamaan Radio Televisyen Malaysia (RTM) bertujuan untuk menampilkan imej dan pakej baru siaran dan program RTM supaya releven dalam perkembangan dunia penyiaran masa kini. Cabaran yang dihadapi oleh RTM tertumpuh kepada peranan dwifungsi utamanya iaitu tanggungjawab sebagai jabatan kerajaan di samping sebuah organisasi penyiaran yang perlu memenuhi citarasa audiens yang sentiasa berubah. Pelbagai usaha dilaksanakan bagi meningkatkan kefahaman audiens terhadap polisi dan dasar kerajaan disamping sajian hiburan yang sesuai kepaada masyarakat umum. Kertas ini membincangkan penjenamaan semula RTM secara besar-besaran pada 1 April 2005 dan kesannya terhadap pendengar radio di Sabah umumnya dan siaran radio RTM Sabah khususnya (Sabah fm, Sabah V fm, Sandakan fm dan Tawau fm) setelah 5 bulan dilaksanakan. Seramai 500 responden telah ditemuramah menggunakan kaedah borang soal selidik terhadap pendengar radio di Sabah termasuk radio RTM Sabah. Hasil kajian mendapati seramai 436 responden (87.2%) telah mendengar radio di Sabah. Daripada jumlah berkenaan sebanyak 44% responden sedar berlakunya penjenamaan semula radio RTM dengan majoritinya memberi penilaian tinggi terhadap pembaharuan nama saluran (88%) berbanding dengan nama program (42.2%) dan lagu pengenalan (39.3%). Seramai 92.7% responden bersetuju bahawa penjenamaan semula radio RTM dapat menarik minat pendengar untuk mengikuti radio -

Tudung Keringkam

The Sarawakiana Series Malay Culture Tudung Keringkam The Sarawakiana Series Tudung Keringkam Kamil Salem Pustaka Negeri Sarawak Kuching 2006 Foreword 'Keringkam Sarawak' is an extraordinary intricate handicraft of Sarawak Malays that combines beautiful patterns into informative culture presentation. This publication hopes to draw attention of everyone, from school children to researchers, likewise, to an almost forgotten, yet, precious handicraft. Culture grows on the shoulders of the community. Its development and sustainability is not a placid travel but an awesome awakening that endures millenniums. Pustaka will continue to collaborate with our partners in the documentation of local and indigenous knowledge as one of the ways to preserve our culture and heritage for future generations. Rashidah Haji Bolhassan Chief Executive Officer Pustaka Negeri Sarawak Introduction 'Tudung Keringkam' is a traditional headscarf One may also wonder whether there is a of Sarawak, and is widely worn by the local possibility of the word 'keringkam' originating Malay women. Handcrafted with fine from the combination of two words, namely, embroidery work, using gold and silver- 'keling' and 'torn'. 'Keling' is a widely-used term coloured coarse threads, tudung keringkam' to describe Indians who originally came from can be classified into two types: 'selayah' (veil) southern India (Kamus Dewan). They came as and 'selendang' (shawl). traders and settled down in South East Asian countries such as Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam 'Selayah Keringkam' is generally worn as a and Indonesia. veil which covers the head right down to the shoulder. Although serving the same function The term 'keling' has been used by the Malays as the former, 'Selendang Keringkam' is (Star 2006) for a long time, even before the relatively longer and is worn right to the waist arrival of the Portuguese, Dutch ana British in level. -

Movement Control and Migration in Sabah in the Time of COVID-19

ISSUE: 2020 No. 135 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 27 November 2020 Movement Control and Migration in Sabah in the Time of COVID-19 Andrew M. Carruthers* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • After a tumultuous state election, Sabah is now the epicenter of an ongoing “Third Wave” of COVID-19 infections that has swept across Malaysia. • Election campaigning and clandestine cross-border movement have been causally linked by different government actors to this Third Wave, prompting the government to tighten movement control orders and migrant surveillance in Sabah. • As a recent report by the Sovereign Migrant Workers Coalition makes clear, migrant detention practices must be reformulated in response to evolving administrative, epidemiological, and ethical challenges. • Policymakers must grasp that (i) movement control, (ii) migrant care, and (iii) public health are interconnected. * Guest writer, Andrew M. Carruthers, is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, and a former Associate and Visiting Fellow at the ISEAS –Yusuf Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2020 No. 135 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION On 25 October 2020, Malaysian King Sultan Abdullah Sultan Ahmad Shah declined to declare a National Emergency, despite Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin’s urging that such an emergency was necessary in the face of an intensifying “Third Wave” of COVID-19 transmission. In a media statement relaying the decision, His Majesty reminded Malaysia’s politicians to “stop all politicking -

The Effect of Educational Aims on the Provision Of

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATIONAL AIMS ON THE PROVISION OF TEXTBOOKS IN MALAYSIA WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE ROLE OF THE TEXTBOOK DIVISION, MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, MALAYSIA. by NORHAYATI HJ.ALIAS A Master's Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Arts degree of the Loughborough University of Technology. September 1991 SUPERVISOR : W.P.MARETT BA Bristol, BA CNAA, MA Cambridge, BCom, BSc (Econ), PhD London, FRHistS Department of Library and Information Studies Loughborough University of Technology ~ by NORHAYATI HJ.ALIAS, 1991. DEDICATION Dedicated to my family with love. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge those people who have assisted, directly and indirectly, in the production of this dissertation. Firstly to my supervisor, I wish to express my profound gratitude, Dr.W.P.Marett for his interest, comments and helpful suggestions, guidance and encouragement throughout this work without which I could not have completed. My sincere gratitude to my parents, who with their enduring affections, have given me the moral and spiritual support which has seen me through. To my husband, without whose patience, understanding and encouragement the project would not have been completed. My special thanks to the staff of the Evaluation Unit and the General Administrative Unit, Textbook Division, Ministry of Education for supplying me with the statistics as required. Lastly, I am particularly indebted "to the Government of Malaysia for awarding me the scholarship and granting me the study -

Newsletter Sekitar Edisi 21 2016

EDISI 21 : 1 - 15 DISEMBER 2016 BAHASA CERMINAN BANGSA DAN BUDAYA Majlis Genta Bahasa Ke-3 Tahun 2016 ms3 Majlis Pelancaran Buku Majlis Anugerah Inovasi Perdana Sekitar Lawatan Delegasi Bank ‘Mempersada Tradisi Keilmuan’ Menteri Dan Sektor Awam 2016 Dunia (World Bank) ms2 ms2 ms4 MAJLIS PELANCARAN BUKU ‘MEMPERSADA TRADISI KEILMUAN’ PULAU PINANG, 4 DISEMBER 2016 - Jabatan Perkhidmatan Awam (JPA) dengan kerjasama Kerajaan Negeri Pulau Pinang telah menganjurkan Majlis Pelancaran Buku ‘Mempersada Tradisi Keilmuan: Syarahan Perdana Transformasi Perkhidmatan Awam Mohamad Zabidi Zainal’ di Rumah Teh Bunga, Georgetown. Majlis yang bermula pada jam 11 pagi ini disempurnakan oleh Tuan Yang Terutama Tun Dato’ Seri Utama (Dr.) Haji Abdul Rahman bin Haji Abbas, Yang di-Pertua Negeri Pulau Pinang. Buku yang diterbitkan oleh JPA dan INTAN ini merupakan kompilasi teks syarahan YBhg. Tan Sri KPPA di lima universiti awam di Malaysia iaitu Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Universiti Malaysia Perlis (UniMAP), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS) dan Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS). MAJLIS ANUGERAH INOVASI PERDANA MENTERI DAN SEKTOR AWAM 2016 PUTRAJAYA, 15 DISEMBER 2016 - Majlis Anugerah Inovasi Perdana Menteri dan Sektor Awam 2016 telah disempurnakan oleh YAB Dato’ Sri Mohd Najib Tun Abdul Razak, Perdana Menteri Malaysia di Grand Ballroom, Hotel Marriott Putrajaya. Majlis yang bertemakan ‘Inovasi Melantasi Konvensi, Inovasi Menjana Produktiviti’ ini merupakan majlis pengiktirafan Sektor Awam yang merangkumi dua (2) peringkat. Peringkat pertama ialah Anugerah Inovasi Perdana Menteri (AIPM) yang merupakan anugerah terunggul dan berprestij bagi mengiktiraf penghasilan inovasi yang signifikan dan berimpak tinggi kepada Negara. Selaras dengan aspirasi Kerajaan untuk membudayakan inovasi dalam kalangan agensi Sektor Awam, AIPM telah diperkenalkan mulai tahun 2010 bagi menggantikan Anugerah Kualiti Perdana Menteri (AKPM). -

Language Policy in Malaysia: Reversing Direction

SARAN KAUR GILL LANGUAGE POLICY IN MALAYSIA: REVERSING DIRECTION (Received 24 February 2005; accepted in revised form 22 May 2005) ABSTRACT. After Independence in 1957, the government of Malaysia set out on a program to establish Bahasa Melayu as official language, to be used in all gov- ernment functions and as the medium of instruction at all levels. For 40 years, the government supported a major program for language cultivation and moderniza- tion. It did not however attempt to control language use in the private sector, including business and industry, where globalization pressure led to a growing demand for English. The demand for English was further fuelled by the forces of the internationalization of education which were met in part by the opening of English-medium affiliates of international universities. In 2002, the government announced a reversal of policy, calling for a switch to English as a medium of instruction at all levels. This paper sets out to analyze the pressures to which the government was responding. KEY WORDS: Bahasa Melayu, economics, English, language modernization, language planning, language policy, language reversal, politics and nationalism, science and technology Introduction1 In the heyday of post-colonial language planning, Malaysia was one of the countries that enthusiastically accepted the arguments of planners and set about to build up its national language. Once independent of British colonial rule, it chose to reduce the role and status of English and select one2 autochthonous language, Bahasa 1 This paper is an adapted version of an earlier paper published in the proceedings of an international conference on ‘‘Integrating Content and Language: Meeting the Challenge of a Multilingual Higher Education.’’ 2004. -

Scholarly Publishing in Malaysia: Origins and Current Development

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 4, Ver. VIII (Apr. 2014), PP 68-73 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Scholarly Publishing in Malaysia: Origins and Current Development 1Hamedi M. Adnan, 2Mohamad Saleeh Rahamad 1,2Department of Media Studies University Malaya 50603 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Abstract: Scholarly books in Malaysia are mainly published by university presses and government’s research institutions. It is carried out as a social responsibility to disseminate knowledge from the researches done, mainly by government servant in the university or research institutions. As such, the number of academic books published in a year is relatively small with limited print-of-run. However, compared with her neighbouring countries, Malaysia has a good structure of governance in scholarly books publishing with the formation of Malaysian Scholarly Books Council or MAPIM which unify all university presses into a single body. This article discusses the history and development of scholarly publishing in Malaysia with the focus to the role of MAPIM of the governing body. Keywords: scholarly publishing; university press; scholarly publishing; books; Southeast Asian publishing I. Introduction Scholarly publishing in Malaysia develops quite slowly although this kind of publication has already existed in the middle of 1950s. In the 1960s there were three scholarly publishing entities in this country, which are University of Malaya Press (UM Press), Language and Literary Agency or Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) and Oxford University Press (OUP). The total number of book titles that were published at this early stage could not be identified since the available source did not separate the quantity of academic and non- academic books. -

MOHAMAD-FITRI-MOHAMAD-YUSOF.Pdf

‘Curriculum Vitae’ BUTIR-BUTIR PERIBADI (Personal Details) Nama Penuh (Full Name) Mohamad Fitri Mohamad Yusoff Gelaran (Title) : Dr. Jawatan (Designation) Pensyarah Kanan/ Timbalan Rektor (Akademik & Penyelidikan) Fakulti Pengajian Kontemporari Islam [email protected] KELAYAKAN AKADEMIK (Academic Qualification) Nama Sijil / Kelayakan Nama Sekolah/Institusi Tahun Bidang pengkhusususan (Certificate/Qualification (Name of School / Institution) (Year (Area of Specialization) obtained) obtained) Doktor Falsafah (Ph.D) Universiti Putra Malaysia 2015 Pengajian Wacana Master Sastera (M.A) Universiti Putra Malaysia 2003 Sosiolinguistik Bahasa Melayu Bacelor Sastera (B.A) Universiti Putra Malaysia 2000 Pakej Dwimajor: 1. Bahasa dan Linguistik Melayu 2. Penulisan dan Kewartawanan Certificate In English Open University 2009 English For Professional For Professional Malaysia (OUM) Communications Communications Sijil Pedagogi Asas Maktab Perguruan Ilmu 2003 Pedagogi Khas, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia. PENGALAMAN SAINTIFIK DAN PENGKHUSUSAN (Scientific experience and Specialisation) Organisasi/ Jawatan/ Tarikh lantikan/ Tarikh tamat/ Kepakaran/ Organization Position Start Date End Date Expertise Yayasan Dakwah Ketua Kluster Media 1 Oktober Wacana Dakwah Islam Malaysia dan Teknologi, Plan 2019 melalui media (YADIM) Pembangunan sosial Dakwah Negara. Dewan Bahasa Panel Penyelidik 15 Julai 2019 Wacana dan Pustaka Kajian Wacana Teks Ekonomi/Muamalat (DBP) Melayu Jabatan Wakaf, Panel Pembangunan 8 April 2019 Komunikasi Zakat dan Haji Modul Latihan (JAWHAR) -

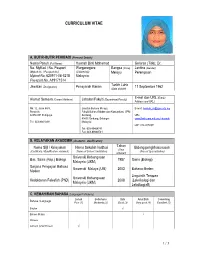

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE A. BUTIR-BUTIR PERIBADI (Personal Details) Nama Penuh (Full Name) Hasnah Binti Mohamad Gelaran (Title): Dr. No. MyKad / No. Pasport Warganegara Bangsa (Race) Jantina (Gender) (Mykad No. / Passport No.) (Citizenship) Melayu Perempuan Mykad No. 620911-08-5218 Malaysia Passport No. A19171514 Tarikh Lahir Jawatan (Designation) Pensyarah Kanan 11 September 1962 (Date of Birth) E-mel dan URL (E-mail Alamat Semasa (Current Address) Jabatan/Fakulti (Department/Faculty) Address and URL) Nb. 12, Jalan 8A/3, Jabatan Bahasa Melayu, E-mail: [email protected] Presint 8, Fakulti Bahasa Moden dan Komunikasi, UPM 62250 WP Putrajaya. Serdang, URL: 43400 Serdang, Selangor www.fbmk.upm.edu.my/~hasnah Tel: 603-88618911 Malaysia H/P: 012-2078911 Tel: 603-89468741 Fax: 603-89468741 B. KELAYAKAN AKADEMIK (Academic Qualification) Nama Sijil / Kelayakan Nama Sekolah Institusi Tahun Bidang pengkhusususan (Year (Certificate / Qualification obtained) (Name of School / Institution) (Area of Specialization) obtained) Universiti Kebangsaan Bac. Sains (Kep.) Biologi 1987 Sains (Biologi) Malaysia (UKM) Sarjana Pengajian Bahasa Universiti Malaya (UM) 2002 Bahasa Moden Moden Linguistik Terapan Universiti Kebangsaan Kedoktoran Falsafah (PhD) 2008 (Leksikologi dan Malaysia (UKM) Leksikografi) C. KEMAHIRAN BAHASA (Language Proficiency) Lemah Sederhana Baik Amat Baik Cemerlang Bahasa / Language Poor (1) Moderate (2) Good (3) Very good (4) Excellent (5) English √ Bahasa Melayu √ Chinese Lain-lain (other):Korean √ 1 / 3 D. PENGALAMAN SAINTIFIK DAN PENGKHUSUSAN -

Islam and Muslims in Southeast Asia, a Bibliography of English-Language

ISlAM AND MUSLIMS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ENGLISH-LANGUAGE PUBLICATIONS 1945-1993 Compiled by Patricia Horvatich Southeast Asia Paper No. 38 Center for Southeast Asian Studies &'hool of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawai'i at Manoa October 1993 PREFACE This bibliography on Islam and Muslims in Southeast Asia has long been in the making. I began compiling references on this subject six years ago when preparing for my comprehensive examinations as a graduate student of anthropology at Stanford University. Work on this bibliography continued as I conducted research on Islam among the Sama people of the Philippines. After completing my dissertation, I was hired by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Hawai'i to teach courses on Islam in Southeast Asia. My research on Islam thus progressed as I prepared lectures and searched for relevant student readings. When Florence Lamoureux, the program coordinator of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, suggested that I publish this bibliography in the Center's series, I made a final attempt to ensure that this work was as complete as possible. I began a systematic search for materials available at the Hamilton Library's Asian Collection at the University of Hawai'i. This search involved use of modern technology in the form of the UHCARL system and CD Rom and also the more familiar, if laborious, method of combing through journals, edited volumes, and bibliographies for pertinent references. As a result of these endeavors, this bibliography assumes its present and, for now, final form. In preparing this bibliography for publication, my priority has been to keep its scope as broad and interdisciplinary as possible by including topics that pertain to history, anthropology, sociology, art, music, literature; education, economics, politics, and law. -

Naquib Al-Attas' Islamization of Knowledge

NAQUIB AL-ATTAS’ ISLAMIZATION OF KNOWLEDGE Its Impact on Malay Religious Life, Literature, Language and Culture Mohd Faizal Musa TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS16/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-08-1 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 16 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 8 1 2021 TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07803 01 Trends_2021-16.indd 1 15/7/21 4:49 PM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07803 01 Trends_2021-16.indd 2 15/7/21 4:49 PM NAQUIB AL-ATTAS’ ISLAMIZATION OF KNOWLEDGE Its Impact on Malay Religious Life, Literature, Language and Culture Mohd Faizal Musa ISSUE 16 2021 21-J07803 01 Trends_2021-16.indd 3 15/7/21 4:49 PM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved.