List of Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Call to Action to Enhance Filovirus Disease Outbreak Preparedness and Response

Viruses 2014, 6, 3699-3718; doi:10.3390/v6103699 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Letter A Call to Action to Enhance Filovirus Disease Outbreak Preparedness and Response Paul Roddy Independent Epidemiology Consultant, Barcelona, 08010, Spain; E-Mail: [email protected] External Editor: Jens H. Kuhn Received: 8 September 2014; in revised form: 23 September 2014 / Accepted: 23 September 2014 / Published: 30 September 2014 Abstract: The frequency and magnitude of recognized and declared filovirus-disease outbreaks have increased in recent years, while pathogenic filoviruses are potentially ubiquitous throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, the efficiency and effectiveness of filovirus-disease outbreak preparedness and response efforts are currently limited by inherent challenges and persistent shortcomings. This paper delineates some of these challenges and shortcomings and provides a proposal for enhancing future filovirus-disease outbreak preparedness and response. The proposal serves as a call for prompt action by the organizations that comprise filovirus-disease outbreak response teams, namely, Ministries of Health of outbreak-prone countries, the World Health Organization, Médecins Sans Frontières, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Atlanta, and others. Keywords: Ebola; ebolavirus; Marburg virus; marburgvirus; Filoviridae; filovirus; outbreak; preparedness; response; data collection; treatment; guidelines; surveillance 1. Introduction Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Marburg virus disease (MVD) in human and non-human primates (NHPs) are caused by seven distinct viruses that produce filamentous, enveloped particles with negative-sense, single-stranded ribonucleic acid genomes. These viruses belong to the Filoviridae family and its Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus genera, respectively [1]. An eighth filovirus, Lloviu virus (LLOV), assigned to the third filovirus genus, Cuevavirus has thus far not been associated with human disease [2,3]. -

Uganda 2015 Human Rights Report

UGANDA 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Uganda is a constitutional republic led since 1986 by President Yoweri Museveni of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party. Voters re-elected Museveni to a fourth five-year term and returned an NRM majority to the unicameral Parliament in 2011. While the election marked an improvement over previous elections, it was marred by irregularities. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The three most serious human rights problems in the country included: lack of respect for the integrity of the person (unlawful killings, torture, and other abuse of suspects and detainees); restrictions on civil liberties (freedoms of assembly, expression, the media, and association); and violence and discrimination against marginalized groups, such as women (sexual and gender-based violence), children (sexual abuse and ritual killing), persons with disabilities, and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) community. Other human rights problems included harsh prison conditions, arbitrary and politically motivated arrest and detention, lengthy pretrial detention, restrictions on the right to a fair trial, official corruption, societal or mob violence, trafficking in persons, and child labor. Although the government occasionally took steps to punish officials who committed abuses, whether in the security services or elsewhere, impunity was a problem. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were several reports the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. On September 8, media reported security forces in Apaa Parish in the north shot and killed five persons during a land dispute over the government’s border demarcation. -

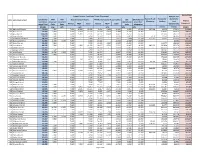

Local Government Quarter 2 Expenditure Limits by Vote and Item

Unconditional Grant Non- Support Services Conditional Grant (Non-wage) Pension and wage Conditional IFMS IPPS Boards and Commisions PAF Monitoring and Accountability DSC EX Gratia and Hard to Reach Pension for Gratuity for Vote Local Government District Grant (Non- Recurrent Recurrent Operational Councillors' Allowances Teachers Local Component wage) Total Costs Costs Normal PRDP Total Normal PRDP Total costs allowances Governments 321469 o/w o/w o/w o/w o/w o/w 212103 212105 321401 501 Adjumani District 70,333 7,500 - 7,030 16,965 23,995 9,614 9,455 19,069 6,569 13,200 357,364 42,075 172,271 112,092 502 Apac District 70,438 7,500 - 7,030 5,902 12,932 17,234 6,313 23,547 11,758 14,700 - 328,001 763,115 164,460 503 Arua District 110,298 7,500 - 7,030 15,105 22,135 26,551 10,070 36,621 25,592 18,450 - 452,432 345,212 356,989 504 Bugiri District 50,557 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 12,143 - 12,143 9,933 13,950 4,171 71,372 385,066 155,982 505 Bundibugyo District 48,218 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 9,657 - 9,657 7,830 16,200 411,325 46,975 270,173 88,150 506 Bushenyi District 61,908 11,786 6,250 7,030 - 7,030 10,543 - 10,543 12,349 13,950 - - 88,534 222,435 507 Busia District 59,123 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 10,280 4,808 15,088 10,305 19,200 - 110,077 155,353 128,289 508 Gulu District 88,745 7,500 - 7,030 9,501 16,532 18,027 9,501 27,529 16,485 20,700 882,273 342,820 255,276 168,801 509 Hoima District 52,515 - - 7,030 - 7,030 14,124 - 14,124 12,162 19,200 - 627,237 136,974 214,390 510 Iganga District 71,706 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 19,245 - 19,245 19,480 18,450 -

Challenges of Development and Natural Resource Governance In

Ian Karusigarira Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival The road that the community expects to take in each generation is inspired and shaped by its memories of former heroic ages —Smith, D.A. (2009) Ian Karusigarira PhD Candidate, Graduate School of Global Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan Abstract In revolutionary political systems—such as Uganda’s—lies a strong collective memory that organizes and enforces national identity as a cultural property. National identity nurtured by the nexus between lived representations and narratives on collective memory of war, therefore, presents itself as a kind of politics with repetitive series of nation-state narratives, metaphorically suggesting how the putative qualities of the nation’s past reinforce the qualities of the present. This has two implications; it on one hand allows for changes in a narrative's cognitive claims which form core of its constitutive assumptions about the nation’s past. This past is collectively viewed as a fight against profanity and restoration of political sanctity; On the other hand, it subjects memory to new scientific heuristics involving its interpretations, transformation and distribution. I seek to interrogate the intricate memory entanglement in gaining and consolidating political power in Uganda. Of great importance are politics of remembering, forgetting and utter repudiation of memory of war while asserting control and restraint over who governs. The purpose of this paper is to understand and internalize the dynamics of how knowledge of the past relates with the present. This gives a precise definition of power in revolutionary-dominated regimes. Keywords: Memory of War, national narratives, victimhood, regime survival, Uganda ―75― 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示4.0国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival 1. -

Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights Helen Liebling-Kalifani

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 4 Article 1 May-2007 Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights Helen Liebling-Kalifani Angela Marshall Ruth Ojiambo-Ochieng Nassozi Margaret Kakembo Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Liebling-Kalifani, Helen; Marshall, Angela; Ojiambo-Ochieng, Ruth; and Kakembo, Nassozi Margaret (2007). Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(4), 1-17. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss4/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2007 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights By Helen Liebling-Kalifani,1 Angela Marshall,2 Ruth Ojiambo-Ochieng,3 and Nassozi Margaret Kakembo4 The effect of the aggressive rapes left me with constant chest, back and abdominal pain. I get some treatment but still, from time to time it starts all over again. It was terrible (Woman discussing the effects of civil war during a Kamuli Parish focus group). Amongst the issues treated as private matters that cannot be regulated by international norms, violence against women and women‟s health are particularly critical. -

PPCR SPCR for Uganda

PPCR/SC.20/6 May 11, 2017 Meeting of the PPCR Sub-Committee Washington D.C. Thursday, June 8, 2017 Agenda Item 6 PPCR STRATEGIC PROGRAM FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE FOR UGANDA PROPOSED DECISION The PPCR Sub-Committee, having reviewed the document PPCR/SC.20/6, Strategic Program for Climate Resilience for Uganda [endorses] the SPCR. The Sub-Committee encourages the Government of Uganda and the MDBs to actively seek resources from other bilateral or multilateral sources to fund further development and implementation of the projects foreseen in the strategic plan. Uganda Strategic Program for Climate Resilience (Uganda SPCR) Republic of Uganda STRATEGIC PROGRAM FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE: UGANDA PILOT PROGRAM FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE (PPCR) Prepared for the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) 2 May, 2017 i Uganda Strategic Program for Climate Resilience (Uganda SPCR) Foreword The Government of Uganda recognizes the effects of climate change and the need to address them within the national and international strategic frameworks. This Strategic Program for Climate Resilience (SPCR) is a framework for addressing the challenges of climate change that impact on the national economy including development of resilience by vulnerable communities. The overall objective of the SPCR is to ensure that all stakeholders address climate change impacts and their causes in a coordinated manner through application of appropriate measures, while promoting sustainable development and a green economy. This SPCR will build on and catalyzes existing efforts in climate resilience-building Programs in Uganda, and will address key identified barriers and constraints, in order to accelerate the transformative accumulation of benefits of climate resilience and sustainable socio-economic development in the targeted sectors and areas. -

Luwero District HRV Profile.Pdf

Luweero District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 Acknowledgement On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Ogwang Jimmy, Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Luwero District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees LUWEERO DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i Table of Contents Acknowledgement .............................................................................................................i -

Uganda: Ebola Preparedness

Page | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Uganda: Ebola Preparedness DREF n° MDRUG041 Glide n° For DREF; Date of issue: 12 September 2018 Expected timeframe: 3 months Operation start date: 11 September 2018 Expected end date: 11 December 2018 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: Yellow DREF allocated: CHF 152,685 IFRC Focal point: National Society Focal point: Josephine Okwera, • Marshal Mukuvare, DM Delegate for East Africa Director of Health, URCS Cluster, will be project manager and overall responsible for planning, implementation, monitoring, reporting and compliances Total number of people at risk: 149,300 people (or Number of people to be assisted: 149,300 people approximately 29,860 households) (or approximately 29,860 households) Host National Society presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Ntoroko branch: 1 focal point, 33 volunteers, Bundibujo branch: 1 staff, 60 volunteers of whom 18 part of the Red Cross Action Team, Kasese branch: 1 staff, 35 volunteers, Kisoro branch: 1 staff, 1 support-staff, 100 volunteers, Kanungo branch: 1 focal point, 33 volunteers Kabarole/Bunangabo branch: 1 staff, 72 volunteers of whom 10 part of the Red Cross Action Team. To date, URCS has deployed 5 staff and 180 volunteers in Bundibugyo, Kasese, Kabarole, Kisoro and Rukungiri/Kanungu districts. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: Alert shared with Movement partners in country: Austrian Red Cross, Belgian-Flanders Red Cross, Canadian Red Cross, German Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross, the ICRC. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: MoH, WHO, UNICEF, UNHCR, IOM, CDC, USAID A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster Following the declaration of the 9th Ebola Disease Outbreak (EVD) on 8 May 2018 by the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) Ministry of Health, the WHO has raised the alert for neighbouring countries of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) which share extensive borders, hosting DRC refugees and are used as corridors for DRC population movement. -

The Uganda Gazettepublished

347 The W. 'BLK'OH CAM’A R, gistrred at the Published General Post Office for tr.msmission nvthin by East Africa as a Authority Seuspaper Uganda Gazette Vol. XCVI No. 55 7th November, 2003 Price: Shs. 1000 CONTENTS Page Reference is made to General Notice No. 305 of 2003 and General Notice No. 306 of 2003. The Electoral Commission Act—Notices............ 347-348 The Companies Act—Notices................................ 348 (a) Insertion after the first paragraph of General Notice No. The Trade Marks Act— Registration of applications 348-352 305 of 2003 and should be made to read as follows: Advertisements ...................................................... 352-353 “By a copy of this Notice. Mr. I Mudoi. the former District Returning Officer. Mubende District is hereby SUPPLEMENTS degazetted accordingly". Bill No. 16—Hie Parliamentary Pensions Bill. 2003. (b) Insertion after the first paragraph of General Notice No. 306 of 2003. should be made to read as follows: Statutory Instruments "By a copy of this Notice. Mr. Peter Gahafu. the former No. 84—The Stamps (Exemption from Stamp Duty) (No. 2) District Returning Officer. Kamuli District is hereby Instrument. 2003. degazetted accordingly". No. 85—The National Environment (Conduct and Certificate of Environmental Practitioners) Regulations. 2003. Reference is made to Statutory Instrument No. 82 of 2003. Acts (a) Title of the Statutory Instrument to include "... and No. 15—The Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act. 2003. Wobulenzi Town Council, thus read No. 16—The Excise Management (Amendment) Act. 2003. No. I”—The Customs Management (Amendment) Act. 2003. "The Electoral Commission. (Appointment of Date of Completion of Update of Voters’ Register in the N’ewlx No. -

Uganda Red Cross Society

UGANDA RED CROSS SOCIETY HEALTH AND CARE DEPARTMENT REPORT ON THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE WORLD SWIM AGAINST MALARIA LONG LASTING INSECTCIDE TREATED NETS-2008 FREE NET MOSQUITO NET DISTRIBUTION Uganda Districts/ branches covered included; Kampala West, Arua, Apac, Kitgum, Luweero, Ntungamo, Bushenyi and Pader INTRODUCTION Uganda Red Cross Society (URCS) is one of the largest and oldest humanitarian organizations in Uganda. It was established by act of parliament in 1964. It ‘s a member of international Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies that brings together the national Red Cross Societies world wide. The Society’s vision is ‘’ An Empowered and Self-Sustaining Community that responds to the needs of the most vulnerable in Uganda.’’ The URCS mission statement is; ‘’to improve the quality of life of the most vulnerable in Uganda as an effective and efficient humanitarian organization.’’ So controlling malaria is part of URCS mandate of reducing vulnerability. In all its operations URCS observes seven cardinal fundamental principles namely; Humanity, Impartiality, Neutrality, Voluntary Service, Unity, and Universality. It is also known for its core values that include transparency, open mindedness, integrity, and stewardship, value for people, equity/equality, responsiveness and time management. URCS has 49 branches covering the whole country with a network of over 150,000 members and volunteers. The volunteer management policy is in place to guide in the management of the vast number of volunteers and this forms the biggest strength of the Society. A big portion of the volunteers is professional and willing to render this professional expertise whenever called upon. In Uganda, malaria is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality especially among children under five years of age and pregnant women. -

1 Strengthening Community Linkages to Ebola Virus Disease (EVD

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH ON EVD IN UGANDA Strengthening Community Linkages to Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) Outbreak Preparedness in Uganda Report on anthropological research on the socio-cultural context of EVD in the most-at-risk districts in Uganda Submitted by: David Kaawa Mafigiri, PhD, MPH Megan Schmidt-Sane, MPH Contact address: Department of Social Work and Social Administration Makerere University, School of Social Sciences P.O Box 7062 Kampala, Uganda Phone: +256 793371781 /773371781 Email: [email protected] Skype: mafigiridk Reporting Date: 17th June 2019 Version: 3.0 1 ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH ON EVD IN UGANDA Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. iv List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... xiv List of Tables and Figures .................................................................................................. xvi Definitions .........................................................................................................................xvii Part One: Background to the Study ...................................................................................... 1 1.1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... -

Gender and Diversity Situational Analysis for C: AVA and GLCI Projects Uganda Country Report July 2010

Gender and Diversity Situational Analysis for C: AVA and GLCI Projects Uganda Country Report July 2010 by: Beatrice Mukasa, Dr Consolata Kabonesa and Adrienne Martin Africa Innovations Institute, Uganda Natural Resources Institute UK. Executive Summary The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation currently funds two major cassava projects in Africa. The Natural Resources Institute (NRI) coordinates the Cassava adding Value for Africa (C:AVA) project which is implemented in five countries, while the Catholic Relief Services (CRS) coordinates the Great Lakes Cassava Initiative (GLCI) which is working in six countries. Both projects operate in Uganda, and recognise the importance of linking the disease and production-focus of GLCI with the market-orientation of the C: AVA project in order to maximize impact on cassava production-productivity-profitability, sustainability and scalability. Gender and diversity was investigated as a key cross-cutting theme in both projects. The Gender and Diversity Situational Analysis was part of the C:AVA cassava value chain studies and scoping studies at community and farmer level in mid-eastern and eastern Uganda (Pallisa. Kamuli, Kumi, Soroti, Amuria and Kaberamaido districts) and was also conducted in the GLCI implementing districts in central Uganda (Nakasongola, Luweero, Nakaseke, Kayunga, Mukono and Kiboga.) The methodology was participatory and largely relied on qualitative approaches through use of organised separate focus group discussions for women and men, as well as in-depth interviews with key informants. The literature reviewed summarises the national and regional policies on gender with particular reference to agricultural and agro enterprise development; the social, cultural and religious influences and regional diversity in gender roles and specifically gender roles in agriculture.