Gamasutra - Features - "Structuring Key Design Elements" Printer Friendly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theescapist 055.Pdf

in line and everything will be just fine. two articles I fired up Noctis to see the Which, frankly, is about how many of us insanity for myself. That is the loneliest think to this day. With the exception of a game I’ve ever played. For those of you who fell asleep during very brave few. the classical mythology portion of your In response to “Development in a - Danjo Olivaw higher education, the stories all go like In this issue of The Escapist, we take a Vacuum” from The Escapist Forum: this: Some guy decides he no longer look at the stories of a few, brave souls As for the fact that thier isolation has In response to “Footprints in needs the gods, sets off to prove as in the game industry who, for better or been a benefit to them rather than a Moondust” from The Escapist Forum: much and promptly gets smacked down. worse, decided that they, too, were hindrance, that’s what I discussed with I’d just like to say this was a fantastic destined to make their dreams a reality. Oveur (Nathan Richardsson) while in article. I think I’ll have to read Olaf Prometheus, Sisyphus, Icarus, Odysseus, Some actually succeeded, while others Vegas earlier this year at the EVE the stories are full of men who, for crashed and burned. We in the game Gathering. The fact that Iceland is such whatever reason, believed that they industry may not have jealous, angry small country, with a very unique culture were not bound by the normal gods against which to struggle, but and the fact that most of the early CCP constraints of mortality. -

Gaming Cover Front

Gaming A Technology Forecast Implications for Community & Technical Colleges in the State of Texas Authored by: Jim Brodie Brazell Program Manager for Research Programs for Emerging Technologies Nicholas Kim IC² Institute Program Director Honoria Starbuck, PhD. Eliza Evans, Ph.D. Michael Bettersworth, M.A. Digital Games: A Technology Forecast Authored by: Jim Brodie Brazell Nicholas Kim Honoria Starbuck, PhD. Program Manager for Research, IC² Institute Eliza Evans, Ph.D. Contributors: Melinda Jackson Aaron Thibault Laurel Donoho Research Assistants: Jordan Rex Matthew Weise Programs for Emerging Technologies, Program Director Michael Bettersworth, M.A. DIGITAL GAME FORECAST >> February 2004 i 3801 Campus Drive Waco, Texas 76705 Main: 254.867.3995 Fax: 254.867.3393 www.tstc.edu © February 2004. All rights reserved. The TSTC logo and the TSTC logo star are trademarks of Texas State Technical College. © Copyright IC2 Institute, February 2004. All rights reserved. The IC2 Institute logo is a trademark of The IC2 Institute at The Uinversity of Texas at Austin. This research was funded by the Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Technical Act of 1998 as administered by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. ii DIGITAL GAME FORECAST >> February 2004 Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................. v List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... -

New Zealand and China

New Zealand and China Reai Alles I had come back ro mv homeland of monstrations against the US aggression in New Zealand from China'in r96o, then Indochinal Against racism in South again in the New Zealand summer of Africa? Against New Zeaiand's partici- 1964-5. This time I arrived at the end pation in the Indochina War as a vassal of of October r97r and stayed until March the US? 1972. True, there is a growing section of New Zealand opinion increasin_gly .thit fs, progressive in its political thinking. Yet the Government ,of New Zealand, while withdrawing its troops from Vietnam, still trains Vietnamese puppet speciatrists in its universities who will go into the US- speak on China were better attended than paid-for warlord army when they return. they had been on past visits. More people It also trains Cambodian officers in really wanted to know about China, es- South Vietnam to strengthen the US pup- pet Lon Nol. Granted that in all of this they do as Australia does, the Australia that also follows the US baton. Australia, that with New Zealand form neo-colonial- ist-controlled bastions of Western imperi- alism in the South Pacific, is now 921)' - did come up each time. T he W ord' Imperialisrn' People, I found, still stick at rhe word exports now go to fapan and the figure is 'imperialism' in any application to New increasing. There are fapanese loans to Zealand, although New Year Honours Australia. Both Australia and New Zea- were still being conferred in the name of Iand then become or start to become eco- the defunct'British Empire'- lons suo- nomic colonies of the revived imperialism posed to be a mernber'of the Corfrmoir- of )apan, and the pace of |apanese eco- weaith and now on the point of being ab- nomic infiltration in every possible 6eld sorbed into the E.E.C. -

EMANA LATINA: Explosion of Culture Fellowships Are Great!

The Technogeeks are at Men's Volleyball and I I it again! Reviews of Women's Tennis Descent II and Congo finish up their seasons ~ see page 8 see page VOLUME XCVII, NUMBER 25 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA FRIDAY, MAY 3, 1996 BY SHAY CHINN about Avery, it seems as though AND ROBERT JOHNSON its design and accommodations are genuinely very livable. Here In hopes of generating ex are the vital statistics: the com citement about the opening of plex will accommodate 136 stu Avery Center, many graduate dents, 33 of which are reserved and undergraduate students were for graduate students. There are introduced to what is expected 38 doubles (four are reserved for to become the new center of on grad students), 50 singles (25 are campus life here at Caltech. On reserved for grad students), 2 Wednesday, an information ses triples, and 4 single suites. Two sion was held at Steele House single suites will share a bath where representatives from room. Avery also contains 4 Mousing and Residence Life spacious faculty apartments as were available to answer ques well as 35 underground parking tions about Avery Center. For spaces. All students and faculty the first time, official tours of the will be required to participate in complex were given which al the 10 meal per week board plan. lowed students to get a prelimi Each room contains an air con nary idea of what the building ditioner, sink, and ethernet con A Brave New World ... will become. nection to the campus network. being that they will not have ises large desks. -

(With) Videogame History Moving Beyond Retrogaming Ahm, Kristian Redhead

(Re)Playing (with) Videogame History Moving Beyond Retrogaming Ahm, Kristian Redhead Publication date: 2018 Citation for published version (APA): Ahm, K. R. (2018, Sep 12). (Re)Playing (with) Videogame History: Moving Beyond Retrogaming. https://www.academia.edu/37325146/_Re_Playing_with_Videogame_History_Moving_beyond_Retrogaming Download date: 26. sep.. 2021 (Re)Playing (with) Videogame History Moving beyond Retrogaming by Kristian Redhead Ahm Master’s Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in IT – Games At The IT-University of Copenhagen, Center for Computer Games Research September 2018 Under the Supervision of Associate Professor Hans-Joachim Backe Resumé Forfatteren af dette speciale har foretaget en kvalitativ undersøgelse, hvor 9 spillere af gamle spil, også kaldet retrogamere, er blevet interviewet om deres motivationer for at spille gamle spil, hvordan de spiller dem og hvor længe. Ved at indtage et fænomenologisk ståsted, ønsker dette speciale at undersøge, hvordan disse gamle spil manifesterer sig i respondenternes livsverdener og hvad dette indebærer for deres opfattelse og brug af disse gamle spil. Denne undersøgelse er blevet betragtet som frugtbar, da den kan problematisere og videreudvikle den nuværende akademiske diskurs omkring retrogaming, der reducerer alle nutidige interaktioner med gamle spil til en aktivitet, der er motiveret af nostalgi. Ved at analysere de indsamlede interviewdata, argumenteres der i dette speciale for, at der eksisterer flere motivationer til at spille gamle spil, udover nostalgi. Dette speciale identificerer fire motivationer udover nostalgi. Den første type, kaldet amatørarkæologen, er interesseret i at spille ”dårlige” og kuriøse gamle spil, på grund af en form for ironisk nydelse og historisk nysgerrighed. -

Opinnäytetyön Mallipohja

Videopelit mediassa: arvostelumedioiden muutos 90- ja 2000-luvuilla Mantere, Ilkka 2013 Kerava Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu Kerava Videopelit mediassa: arvostelumedioiden muutos 90- ja 2000-luvuilla Ilkka Mantere Tietojenkäsittelyn koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Marraskuu, 2013 Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu Tiivistelmä Laurea Kerava Tietojenkäsittelyn koulutusohjelma Mantere, Ilkka Videopelit mediassa: arvostelumedioiden muutos 90- ja 2000-luvuilla Vuosi 2013 Sivumäärä 54 Tämän opinnäytetyön tavoitteena on selvittää, miten videopelien arvostelu eri medioissa on muuttunut. Tavoitteena on selvittää, mistä pelaajat nykyään katsovat arvosteluja, mihin ar- vosteluihin he luottavat ja mitä arvostelumediaa lehdistä, televisiosta ja Internetistä he pitä- vät tärkeimpänä. Lisäksi kerrotaan videopelikonsolien ja suomalaisten videopeliohjelmien his- toriasta, sillä Suomessa on luotu sekä maailman ensimmäinen videopeleihin keskittynyt kana- va MoonTV että ulkomaillakin levitykseen päässyt peliohjelmaformaatti Tilt. Konsolien historiasta kirjoittamista varten käytetään joitakin kirjalähteitä, lähinnä englannin- kielisiä, koska kattavia konsolien historiaa kunnolla käsitteleviä kirjoja ei tunnu olevan suo- meksi tarjolla. Lähteinä käytetään myös Internetistä löytyviä videopeliaiheisia videoita, jotka viihteellisyydestään huolimatta tarjoavat paljon tietoa videopelien historiasta. Tutkimus on tehty yhdistellen kvantitatiivista tutkimusta käyttäen verkkolomaketta, minkä lisäksi käytettiin, näkökulman laajentamiseksi ja tiedonsaantiin, sähköpostihaastatteluja -

Deus Ex (2000) by Ion Storm Inc

A zeitgeist game is reflective of its corresponding social climate. Titles that gain zeitgeist status have in some way challenged the norms of their associated era and revolutionised a pre-established genre by bending traditional conventions. Thus, zeitgeist titles are also timeless. They transcend time, remaining popular and famous due to the societal standpoints they raise and the impact their innovation has on the wider gaming communities and markets. Sci-Fi cyberpunk FPS/RPG Deus Ex (2000) by Ion Storm Inc. is an example of one such title that has built upon its sociological, artistic and technical influences to create a game that resonates innovation through its unique application of emergent gameplay; driven by character interaction and choice. Through analysis of these three fundamental influences in relation to the unique emergent gameplay construction of Deus Ex and correspondingly by comparing the game with its peers gives insight into how this game achieved zeitgeist status. Deus Ex was not the first game to challenge the norm by hybridising FPS/RPG genres. It was inspired by the gameplay of previous FPS/RPG 90’s games Ultima Underworld (1992) and System Shock (1994) by Looking Glass. (Spector, 2000). However, Spector also states he wanted to build upon the foundation laid by these games. He goes on to say his influence for the setting of the game came from his research into millennial conspiracies and his wife’s obsession with the X-Files. (2000). The game world of Deus Ex acts as a basis for the innovative success of its emergent gameplay. Without a lively game world gameplay choices would feel uninspiring. -

Video Game Collection MS 17 00 Game This Collection Includes Early Game Systems and Games As Well As Computer Games

Finding Aid Report Video Game Collection MS 17_00 Game This collection includes early game systems and games as well as computer games. Many of these materials were given to the WPI Archives in 2005 and 2006, around the time Gordon Library hosted a Video Game traveling exhibit from Stanford University. As well as MS 17, which is a general video game collection, there are other game collections in the Archives, with other MS numbers. Container List Container Folder Date Title None Series I - Atari Systems & Games MS 17_01 Game This collection includes video game systems, related equipment, and video games. The following games do not work, per IQP group 2009-2010: Asteroids (1 of 2), Battlezone, Berzerk, Big Bird's Egg Catch, Chopper Command, Frogger, Laser Blast, Maze Craze, Missile Command, RealSports Football, Seaquest, Stampede, Video Olympics Container List Container Folder Date Title Box 1 Atari Video Game Console & Controllers 2 Original Atari Video Game Consoles with 4 of the original joystick controllers Box 2 Atari Electronic Ware This box includes miscellaneous electronic equipment for the Atari videogame system. Includes: 2 Original joystick controllers, 2 TAC-2 Totally Accurate controllers, 1 Red Command controller, Atari 5200 Series Controller, 2 Pong Paddle Controllers, a TV/Antenna Converter, and a power converter. Box 3 Atari Video Games This box includes all Atari video games in the WPI collection: Air Sea Battle, Asteroids (2), Backgammon, Battlezone, Berzerk (2), Big Bird's Egg Catch, Breakout, Casino, Cookie Monster Munch, Chopper Command, Combat, Defender, Donkey Kong, E.T., Frogger, Haunted House, Sneak'n Peek, Surround, Street Racer, Video Chess Box 4 AtariVideo Games This box includes the following videogames for Atari: Word Zapper, Towering Inferno, Football, Stampede, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ms. -

October 1999

OCTOBER 1999 GAME DEVELOPER MAGAZINE ON THE FRONT LINE OF GAME INNOVATION GAME PLAN DEVELOPER 600 Harrison Street, San Francisco, CA 94107 t: 415.905.2200 f: 415.905.2228 w: www.gdmag.com Graphics Fly... Publisher Cynthia A. Blair cblair@mfi.com EDITORIAL Will Developers Fry? Editorial Director Alex Dunne [email protected] Managing Editor his heard at a Siggraph panel: pricing” — $5,000 or less per product, Kimberley Van Hooser [email protected] “Consumer graphics cards in no royalties). These will be inexpensive Departments Editor two years will be more power- tools that even junior developers can Jennifer Olsen [email protected] ful than any graphics card learn in a few weeks, and which can be Art Director T Laura Pool lpool@mfi.com available today at any price.” That’s integrated into a game quickly. Where Editor-At-Large quite a bold prediction, but I agree. will we get these dream tools? That Chris Hecker [email protected] Graphics hardware has entered a phe- brings me to my second point. Contributing Editors nomenal technological growth spurt, At Siggraph, it was evident that the Jeff Lander [email protected] Paul Steed [email protected] thanks in part to the demands of graphics research community desires Omid Rahmat [email protected] today’s games. The latest crop of con- closer ties to the game development Advisory Board sumer 3D chips, such as Nvidia’s industry. The problem is, researchers Hal Barwood LucasArts GeForce 256 (formerly known as NV10), don’t know how to build those relation- Noah Falstein The Inspiracy Brian Hook Verant Interactive 4 boasts features that were found exclu- ships with us, how to identify what Susan Lee-Merrow Lucas Learning sively on high-end workstation cards aspects of their research we might find Mark Miller Harmonix Dan Teven Teven Consulting only a year ago. -

Microsoft Acquires Massive, Inc

S T A N F O R D U N I V E R S I T Y! 2 0 0 7 - 3 5 3 - 1! W W W . C A S E W I K I . O R G! R e v . M a y 2 9 , 2 0 0 7 MICROSOFT ACQUIRES MASSIVE, INC. May 4th, 2006 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1. Introduction 2. Industry Overview 2.1. The Advertising Opportunity Within Video Games 2.2. Market Size and Demographics 2.3. Video Games and Advertising 2.4. Market Dynamics 3. Massive, Inc. ! Company Background 3.1. Founding of Massive 3.2. The Financing of Massive 3.3. Product Launch / Technology 3.4. The Massive / Microsoft Deal 4. Microsoft, Inc. within the Video Game Industry 4.1. Role as a Game Publisher / Developer 4.2. Acquisitions 4.3. Role as an Electronic Advertising Network 4.4. Statements Regarding the Acquisition of Massive, Inc. 5. Exhibits 5.1. Table of Exhibits 6. References ! 2 0 0 7 - 3 5 3 - 1! M i c r o s o f t A c q u i s i t i o n o f M a s s i v e , I n c .! I N T R O D U C T I O N In May 2007, Microsoft Corporation was a company in transition. Despite decades of dominance in its core markets of operating systems and desktop productivity software, Mi! crosoft was under tremendous pressure to create strongholds in new market spaces. -

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

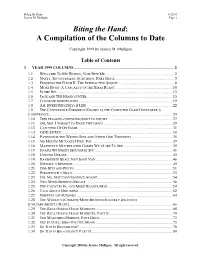

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29 -

42Pcpowerplay

42 PCPOWERPLAY THE MASTER OF IMMERSION Warren Spector talks choice and consequence, why playstyle matters, and the future of the PC’s most captivating sub-genre ORIGIN, LooKING GlASS, f I pulled out a gun in this restaurant, Spector holsters his weapon. it would be the biggest moment of “We’re the only medium that asks AND IoN STORM. ULTIMA “I my life,” says Warren Spector. We’re questions. That is the fundamental UNDERWORLD, SYSTEM having lunch on Melbourne’s Southbank difference between games and everything Promenade, overlooking the Yarra River. else. Not to do that is a sin.” SHOCK, AND DEUS EX. His hand appears from his pocket, I decide it’s probably best to ask thumb and forefinger extended in the another question. THESE ARE SOME OF THE shape of a pistol. He takes aim over MOST IMPORTANT PC my shoulder at a quiet man enjoying an PUNK PHILOSOPHY equally quiet seafood platter. Talk to people at Spector’s studio, Junction DEVEloPERS, AND THEIR “That guy is going to start screaming,” Point, and they’ll describe him as the guy MOST ENTHRAllING GAMES. he says. The man doesn’t notice. who yells all the time. Spector changes targets, acquiring a “I have very little patience for fools,” THEY All BEloNG TO A FAMILY fashionable young couple sitting behind he tells me. “If I think you’re stupid, him. “Those people over there are going to you’re going to know about it. I’m a real KNOWN AS THE IMMERSIVE draw their own guns,” he calculates. jerk, honestly.” SIMULATION.