An International Journal for Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 42 Issue 2 August 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFRICANUS JOURNAL Vol

AFRICANUS JOURNAL Vol. 13 No. 1 | April 2021 africanus journal vol. 13, no. 1 April 2021 Contents 3 Goals of the Journal 3 Life of Africanus 3 Other Front Matter 5 Inaugural Acceptance Speech Fall 1969 Harold John Ockenga 9 Serving the Global Church as a World Christian Daewon Moon 13 Not by Might or Power but by My Spirit Ursula Williams 19 Boulders, Bridges, and Destiny and the Often-Obscure Connections William C. Hill 23 God's Masterpiece Wilma Faye Mathis 29 My Spiritual Journey of Maturing (or Growing) in God's Love and Faithfulness Leslie McKinney Attema 35 Navigating between Contexts and Texts for Ministry as Theological- Missional Calling while Appreciating the Wisdom of Retrievals for Renewal and Lessons Learned from My Early Seminary Days David A. Escobar Arcay 39 Review of Why Church? A Basic Introduction Jinsook Kim 41 Review of 1 Timothy and 2 Timothy and Titus Jennifer Creamer 44 Review of The Story of Creeds and Confessions: Tracing the Development of the Christian Faith William David Spencer 48 Review of Serve the People Jeanne DeFazio 1 50 Review of Three Pieces of Glass: Why We Feel Lonely in a World Mediated by Screens Dean Borgman 54 Review of Healing the Wounds of Sexual Abuse: Reading the Bible with Survivors Jean A. Dimock 57 Review of A Defense for the Chronological Order of Luke's Gospel Hojoon J. Ahn 2 Goals of the Africanus Journal The Africanus Journal is an award-winning interdisciplinary biblical, theological, and practical journal of the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME). -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer 'Dating the Death of Jesus' Citation for published version: Bond, H 2013, ''Dating the Death of Jesus': Memory and the Religious Imagination', New Testament Studies, vol. 59, no. 04, pp. 461-475. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688513000131 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0028688513000131 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: New Testament Studies Publisher Rights Statement: © Helen Bond, 2013. Bond, H. (2013). 'Dating the Death of Jesus': Memory and the Religious Imagination. New Testament Studies, 59(04), 461-475doi: 10.1017/S0028688513000131 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Dating the Death of Jesus: Memory and the Religious Imagination Helen K. Bond School of Divinity, University of Edinburgh, Mound Place, Edinburgh, EH1 2LX [email protected] After discussing the scholarly preference for dating Jesus’ crucifixion to 7th April 30 CE, this article argues that the precise date can no longer be recovered. All we can claim with any degree of historical certainty is that Jesus died some time around Passover (perhaps a week or so before the feast) between 29 and 34 CE. -

Catalogue 2008-2009

1725 Bear Valley Parkway Escondido, CA 92027 (888) 480.8474 (760) 480.0252 fax www.wscal.edu CATALOGUE 2008-2009 westminster seminary california From the President Do you believe the gospel of Jesus Christ? Do you want to understand the Bible more deeply and faithfully? Do you desire to serve Christ and his church? If your answer is “yes,” then Westminster Seminary California (WSC) is an excellent place for you. Here you will discover a community of faith and study, of fellowship and prayer. At WSC, you will find an encouraging place to reflect on and prepare for your calling from Christ. We hope that this catalogue will help you get to know us better. As you look through it, you may want to notice, in particular, our commitments, our faculty, our programs, and our facilities. We are committed to the gospel of Christ as taught by the inerrant Scriptures and as summarized in our Reformed confessions of faith. Our faculty is outstanding. Each member is an experienced pastor and an excellent teacher. They are active in their churches and committed to helping students in and out of the classroom. Their academic credentials are impressive, and they are active in research and writing in their fields. The Seminary offers two primary programs of study. First is the three-year Master of Divinity program. This program is carefully designed to prepare men for the ordained pastoral ministry. Second is the two-year Master of Arts program. With concentrations in biblical, theological and historical theological studies, it encourages women and men to pursue their own interests in preparation for various kinds of service in Christ’s kingdom. -

Why Religious People Believe What They Shouldn't: Explaining Theological Incorrectness in South Asia and America

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 8-2002 Why Religious People Believe What They Shouldn't: Explaining Theological Incorrectness in South Asia and America D. Jason Slone Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Slone, D. Jason, "Why Religious People Believe What They Shouldn't: Explaining Theological Incorrectness in South Asia and America" (2002). Dissertations. 1333. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1333 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHY RELIGIOUS PEOPLE BELIEVE WHAT THEY SHOULDN’T: EXPLAINING THEOLOGICAL INCORRECTNESS IN SOUTH ASIA AND AMERICA by D. Jason Slone A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Religion Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2002 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WHY RELIGIOUS PEOPLE BELIEVE WHAT THEY SHOULDN’T: EXPLAINING THEOLOGICAL INCORRECTNESS IN SOUTH ASIA AND AMERICA D. Jason Slone, Phi). Western Michigan University, 2002 Cross-cultural descriptions of religious thought and behavior in South Asia and America show that people commonly hold ideas and perform actions that seem to be not only conceptually incoherent but also “theologically incorrect” by the standards of their own traditions. -

Retrieval and the Doing of Theology

Volume 23 · Number 2 Summer 2019 Retrieval and the Doing of Theology Vol. 23 • Num. 2 Retrieval and the Doing of Theology Stephen J. Wellum 3 Editorial: Reflections on Retrieval and the Doing of Theology Kevin J. Vanhoozer 7 Staurology, Ontology, and the Travail of Biblical Narrative: Once More unto the Biblical Theological Breach Stephen J. Wellum 35 Retrieval, Christology, and Sola Scriptura Gregg R. Allison 61 The Prospects for a “Mere Ecclesiology” Matthew Barrett 85 Will the Son Rise on a Fourth Horizon? The Heresy of Contemporaneity within Evangelical Biblicism and the Return of the Hermeneutical Boomerang for Dogmatic Exegesis Peter J. Gentry 105 A Preliminary Evaluation and Critique of Prosopological Exegesis Pierre Constant 123 Promise, Law, and the Gospel: Reading the Biblical Narrative with Paul SBJT Forum 137 Gregg R. Allison 157 Four Theses Concerning Human Embodiment Book Reviews 181 Editor-in-Chief: R. Albert Mohler, Jr. • Editor: Stephen J. Wellum • Associate Editor: Brian Vickers • Book Review Editor: John D. Wilsey • Assistant Editor: Brent E. Parker • Editorial Board: Matthew J. Hall, Hershael York, Paul Akin, Timothy Paul Jones, Kody C. Gibson • Typographer: Benjamin Aho • Editorial Office: SBTS Box 832, 2825 Lexington Rd., Louisville, KY 40280, (800) 626-5525, x 4413 • Editorial E-Mail: [email protected] Editorial: Reflections on Retrieval and the Doing of Theology Stephen J. Wellum Stephen J. Wellum is Professor of Christian Theology at The Southern Baptist Theo- logical Seminary and editor of Southern Baptist -

Manipulation and Moral Standing: an Argument for Incompatibilism

Philosophers’ volume 12, no. 7 Oh, Thou, who didst with Pitfall and with Gin march 2012 Beset the Road I was to wander in, Imprint Thou wilt not with Predestination round Enmesh me, and impute my Fall to Sin? —The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Verse LVII 1. Introduction Manipulation and Moral A prominent recent strategy for advancing the thesis that moral respon- sibility is incompatible with causal determinism has been to argue that agents who meet compatibilist conditions for responsibility can never- theless be subject to responsibility-undermining manipulation. If mor- Standing: An Argument al responsibility is compatible with causal determinism, so the thought goes, it must also be compatible (for instance) with the thesis that a given agent designed the world at some past time precisely so as to make it causally inevitable that one performs the particular bad actions for Incompatibilism one performs. In short, compatibilism has it that our responsibility is consistent with the thesis that all of our actions, down to the finest de- tails, are the inevitable outcomes of the designs of some further agent “behind the scenes”. According to the incompatibilist, however, once we became aware that agents had been “set up” in this way, we should no longer judge that they are responsible for their behavior, nor should we hold them responsible for it by blaming them, in case what they did was wrong. Manipulation arguments so far have thus focused on what our response to manipulated agents should be. Incompatibilists allege that, intuitively, we should no longer regard such agents as responsible. -

Towards a Renewed Theology of Personal Agency: Origen’S Theological Vision and the Challenges of Fatalism and Determinism Bernard B

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations Student Scholarship 9-2018 Towards a Renewed Theology of Personal Agency: Origen’s Theological Vision and the Challenges of Fatalism and Determinism Bernard B. Poggi [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Poggi, Bernard B., "Towards a Renewed Theology of Personal Agency: Origen’s Theological Vision and the Challenges of Fatalism and Determinism" (2018). Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations. 37. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations/37 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS A RENEWED THEOLOGY OF PERSONAL AGENCY: ORIGEN’S THEOLOGICAL VISION AND THE CHALLENGES OF FATALISM AND DETERMINISM. A thesis by Rev. Bernard B. Poggi presented to The Faculty of the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Licentiate of Sacred Theology Berkeley, California September 2018 Committee Signatures _____________________________________ __________ Thomas Cattoi, Ph. D., Director Date _____________________________________ __________ Marianne Farina, CSC, Ph.D., Reader Date ii Abstract TOWARDS A RENEWED THEOLOGY OF PERSONAL AGENCY: ORIGEN’S THEOLOGICAL VISION AND THE CHALLENGES OF FATALISM AND DETERMINISM Rev. Bernard B. Poggi In our own contemporary context, there seems to be nothing more important than for a person to be able to speak about their achievements as being specifically their own. -

The Current Body-Soul Debate: a Case for Dualistic Holism John W

The Current Body-Soul Debate: A Case for Dualistic Holism John W. Cooper OVERVIEW ics. It surveys why the debate about the body and he title of a recent anthology, In Search soul developed, introduces the current positions, Tof the Soul, reflects the current diversity of and identifies the important biblical, theological, opinion and occasional confusion among Chris- philosophical, scientific, ethical, and practical- tian scholars about the constitution of humans as pastoral issues involved. It argues that dualistic body and soul. Four evangelical philosophers each holism—the existential unity but temporary sepa- present different theories of body and soul, only ration of body and soul—remains the most ten- 2 John W. Cooper is Professor of some of which are consistent with able view. Philosophical Theology at Calvin historic doctrine, and the book’s Theological Seminary in Grand introduction raises more ques- HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE Rapids, Michigan. tions about the traditional view CURRENT POSITIONS 1 Dr. Cooper served in the United than about recent alternatives. Traditional Positions States Army as a Chaplain’s It may surprise ordinary church Throughout history, the ecumenical Christian Assistant. From there he continued members to learn that, for a gen- tradition—Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catho- his studies at the University eration, Christian academics have lic, and most historic Protestant churches—has of Toronto and then at Calvin Theological Seminary. He taught vigorously debated which theory of affirmed that God created humans as unities of Philosophy at Calvin College body and soul best reflects proper body and soul but that disembodied souls exist in from 1978 to 1985, when he joined exegesis of Scripture, sound phi- an intermediate state between death and resurrec- the seminary faculty. -

Systematic Theology Christology, Soteriology, Eschatology

ST 517/01 Syllabus Spring 2019 Reformed Theological Seminary Systematic Theology Christology, Soteriology, Eschatology Meeting Information Meeting Time: Tuesdays, 8:00 AM–12:00 PM (February 5 – May 14) Meeting Place: Contact Information Prof.: D. Blair Smith (office: lower level in E building) Office Phone: 704-366-5066 (x4223) Email: [email protected] Hours: Mondays 3:00 PM–5:00 PM and by appointment Teacher Assistant: Nate Groelsema ([email protected]) Course Description This course will systematically present biblical teaching on the topics of Christology, Soteriology, and Eschatology as understood and taught within the Reformed tradition, demonstrating that these formulations (1) represent the proper understanding of Scripture, (2) inherit and carry forward the best of the ancient teachings of the Church, and (3) provide the people of God the doctrine needed in order to thrive as disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ in the twenty-first century. Course Objectives 1. To base all of our theology of the Christology, Soteriology, and Eschatology in God’s revelation in Scripture. 2. To enable the student to better grasp related doctrines through familiarity with their exegetical and theological foundations, while also being acquainted with both relevant historical and contemporary discussions, so that they can clearly and confidently communicate them in preaching, teaching, and counseling. 3. To explore and appreciate the confessional expressions concerning these doctrines within the Reformed tradition, especially in the Westminster Standards. Texts and Abbreviations Summary (required) RD: Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics: Abridged in One Volume, pp. 393-586; 693-777 (chapters 14-20; 23-25) THS: Sinclair B. Ferguson, The Holy Spirit, pp. -

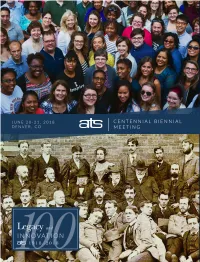

Biennial Program Book

Our mission To promote the improvement and enhancement of theological schools to the benefit of communities of faith and the broader public. Top cover photo—Copyright: Wesley Theological Seminary, 2017. Used with permission. Contents Hotel Floorplan iv Meeting Agenda 1 Workshops 4 Innovation Expo 7 Participants in the Program 12 Officers and Directors 14 Message from the Executive Director 16 ATS Distinguished Service Awards 17 Past ATS Presidents 18 Past Commission on Accrediting Chairs 19 Past Biennial Meeting Sites 20 ATS Milestones 21 Rules for the Conduct of Business 22 COMMISSION ON ACCREDITING BUSINESS Report of the Board of Commissioners 24 Motion and Process for Redevelopment of the Standards 32 Proposed Revisions to the Commission Bylaws 41 Report of the Commission Treasurer 44 Report of the Commission Nominating Committee 47 ASSOCIATION BUSINESS Report of the Association Board of Directors 50 Membership Report 55 Associate Membership Applicants 56 Affiliate Status Applicants 78 Plan for the Work of ATS: 2018–2024 80 Proposed Revisions to the Association Bylaws 85 Report of the Association Treasurer 88 Report of the Association Nominating Committee 92 REPORTS Committee on Race and Ethnicity 94 Economic Challenges Facing Future Ministers Project 96 Educational Models and Practices in Theological Education Project 98 Faculty Development Advisory Committee 102 Global Awareness and Engagement Initiative 104 Governance in Theological Schools Initiative 105 Leadership Education Program 106 Henry Luce III Fellows in Theology 108 Research and Data Advisory Committee 110 Science for Seminaries Projects 112 Student Data and Resources Advisory Committee 114 Theological Education Editorial Board 116 Women in Leadership Advisory Committee 117 Forum for Theological Exploration, Inc 119 iii Hotel Floorplan iv AGENDA Meeting Agenda TUESDAY, JUNE 19 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. -

Ordained Servant a Journal for Church Officers a Publication of the Committee on Christian Education of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church

OrdainedServant A Journal for Church Officers VOLUME 24, 2015 Ordained Servant A Journal for Church Officers A publication of the Committee on Christian Education of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church ISSN 1525-3503 Volume 24 2015 Editor: Gregory Edward Reynolds • 827 Chestnut Street • Manchester, NH 03104 Telephone: 603-668-3069 • Electronic mail: [email protected] Website: www.opc.org/os.html Ordained Servant is published monthly (except for combined issues June/July and August/September) online as Ordained Servant Online (E-ISSN 1931-7115, online edition), and printed annually (ISSN: 1525-3503) after the end of each calendar year, beginning with volume 15 (2006) published in 2007. Ordained Servant was published quarterly in print from 1992 through 2005. All 53 issues are available in our online archives. The editorial board is the Subcommittee on Serial Publications of the Committee on Christian Education. Subscriptions: Copies of the annual printed edition of Ordained Servant are sent to each ordained minister of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, each organized congregation, and each designated mission work, and are paid for by the Committee. Ordained elders, deacons, and licentiates of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church may receive copies gratis upon request. Ordained Servant is also available to anyone in the U.S. and Canada who wishes to subscribe by remitting $10.00 per year to: Ordained Servant, The Orthodox Presbyterian Church, 607 N. Easton Rd., Bldg. E, Willow Grove, PA 19090-2539. Checks should be made out to the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, designated for Ordained Servant in the memo line. Institutional subscribers in the US and Canada please remit $15.00 per year. -

New College Magazine 2019 (PDF)

NEW COLLEGE MAGAZINE2019 “ A VERY BRITISH TOUR-DE-FORCE” Miles Jupp Comedian, actor and alumnus P10 12 NEW COLLEGE NEWS HISTORY MAKERS YOUR NEWS Stories from around the School P4 A landmark year for women P7 Alumni updates P14 NEW COLLEGE 2019 EDITOR’S NOTE School of Divinity, University of Edinburgh, Mound Place, Edinburgh EH1 2LX. Tel: +44 131 650 8959 Email: [email protected] Website www.ed.ac.uk/divinity Facebook.com/SchoolOfDivinityEdinburgh Twitter.com/SchoolofDiv Welcome to New College, the School of Divinity’s annual © The University of Edinburgh March 2019. No part of this publication may be reproduced in magazine, formerly known as the Bulletin. I am honoured to any form without prior written consent. The views follow Emeritus Professor Larry Hurtado as editor. We are expressed are those of the contributors and do indebted to him for his contributions over a number of years, not necessarily represent those of the School and wish him well in his retirement. 2 of Divinity, New College or the University of Edinburgh. In these pages, you will find a window into an energetic, Change of address? engaging community of scholarship, already looking forward If you have changed address, please let us to its 175th year (see p 5). know. Contact the University’s Development and Alumni office on +44 (0)131 650 2240 or email This year’s magazine includes a lead article on our alumnus [email protected] Miles Jupp (MA Divinity, 2005), whose path, post-New The University of Edinburgh is a charitable body College, has taken him to radio, television, and more recently, registered in Scotland, with registration number Hollywood.