Setting up Safti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

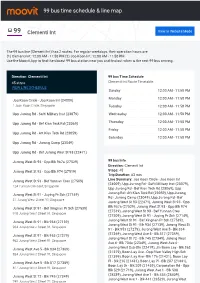

99 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

99 bus time schedule & line map 99 Clementi Int View In Website Mode The 99 bus line (Clementi Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clementi Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Joo Koon Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 99 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 99 bus arriving. Direction: Clementi Int 99 bus Time Schedule 45 stops Clementi Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009) 1 Joon Koon Circle, Singapore Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069) Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Friday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059) Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Jurong Camp (23049) Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Jurong West St 93 (22471) Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529) 99 bus Info Direction: Clementi Int Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 974 (27519) Stops: 45 Trip Duration: 63 min Jurong West St 93 - Bef Yunnan Cres (27509) Line Summary: Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009), Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079), 124 Yunnan Crescent, Singapore Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069), Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059), Upp Jurong Jurong West St 91 - Juying Pr Sch (27149) Rd - Jurong Camp (23049), Upp Jurong Rd - Bef 31 Jurong West Street 91, Singapore Jurong West St 93 (22471), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk -

SAFTI MI 50Th Anniversary

TABLE OF CONTENTS Message by Minister for Defence 02 TOWARDS EXCELLENCE – Our Journey 06 Foreword by Chief of Defence Force 04 TO LEAD – Our Command Schools 30 Specialist and Warrant Officer Institute 32 Officer Cadet School 54 Preface by Commandant 05 SAF Advanced Schools 82 SAFTI Military Institute Goh Keng Swee Command and Staff College 94 TO EXCEL – Our Centres of Excellence 108 Institute for Military Learning 110 Centre for Learning Systems 114 Centre for Operational Learning 119 SAF Education Office 123 Centre for Leadership Development 126 TO OVERCOME – Developing Leaders For The Next 50 Years 134 APPENDICES 146 Speeches SAFTI was the key to these ambitious plans because our founding leaders recognised even at the inception of the SAF that good leaders and professional training were key ingredients to raise a professional military capable of defending Singapore. MESSAGE FROM MINISTER FOR DEFENCE To many pioneer SAF regulars, NSmen and indeed the public at large, SAFTI is the birthplace of the SAF. Here, at Pasir Laba Camp, was where all energies were focused to build the foundations of the military of a newly independent Singapore. The Government and Singaporeans knew what was at stake - a strong SAF was needed urgently to defend our sovereignty and maintain our new found independence. The political battles were fought through the enactment of the SAF and Enlistment Acts in Parliament. These seminal acts were critical but they were but the beginning. The real war had to be fought in the community, as Government and its Members of Parliament convinced each family to do their duty and give up their sons for military service. -

New Zealand Defence Minister Calls on Dr Tan

New Zealand Defence Minister Calls on Dr Tan 30 Sep 1998 The New Zealand Minister for Defence, the Honourable Mr Max Bradford, called on the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, Dr Tony Tan, this morning, 30 Sep 98, at the Ministry of Defence, Gombak Drive. Upon his arrival at MINDEF, Mr Bradford reviewed a Guard-of-Honour. Mr Bradford is here on his introductory visit from 29 Sep to 2 Oct 98. Mr Bradford will call on Acting Prime Minister BG (NS) Lee Hsien Loong, and deliver the second lecture in the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) "Strategic Challenges of the Asia Pacific" lecture series on 2 Oct 98. On the same day, Mr Bradford will visit the inaugural Ex SINGKIWI, a bilateral exercise between the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) and the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), at Paya Lebar Air Base (PLAB). RNZAF A-4K Skyhawks, and RSAF F-5 Tiger, F-16 Fighting Falcon and A-4SU Super Skyhawk fighter aircraft are conducting a range of air training activities under the exercise from 21 Sep to 2 Oct 98. Whilst at PLAB, he will also be shown the RSAF's Air Combat Manoeuvring Instrumentation (ACMI) system. Mr Bradford's programme includes visits to SAFTI Military Institute, Tuas Naval Base, Headquarters Artillery, Tengah Air Base, and Changi Air Base for the annual Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA) Training Affiliation between the RNZAF's P-3K squadron and the RSAF's Fokker 50 squadron. Singapore and New Zealand have a long-standing defence relationship, and this has strengthened significantly in recent years. -

JURONG Heritage Trail

T he Jurong Heritage Trail is part of the National Heritage Board’s ongoing efforts » DISCOVER OUR SHARED HERITAGE to document and present the history and social memories of places in Singapore. We hope this trail will bring back fond memories for those who have worked, lived or played in the area, and serve as a useful source of information for new residents JURONG and visitors. HERITAGE TRAIL » CONTENTS » AREA MAP OF Early History of Jurong p. 2 Historical extent of Jurong Jurong The Orang Laut and early trade routes Early accounts of Jurong The gambier pioneers: opening up the interior HERITAGE TRAIL Evolution of land use in Jurong Growth of Communities p. 18 MARKED HERITAGE SITES Villages and social life Navigating Jurong Beginnings of industry: brickworks and dragon kilns 1. “60 sTalls” (六十档) AT YUNG SHENG ROAD ANd “MARKET I” Early educational institutions: village schools, new town schools and Nanyang University 2. AROUND THE JURONG RIVER Tide of Change: World War II p. 30 101 Special Training School 3. FORMER JURONG DRIVE-IN CINEMA Kranji-Jurong Defence Line Backbone of the Nation: Jurong in the Singapore Story p. 35 4. SCIENCE CENTRE SINGAPORE Industrialisation, Jurong and the making of modern Singapore Goh’s folly? Housing and building a liveable Jurong 5. FORMER JURONG TOWN HALL Heritage Sites in Jurong p. 44 Hawker centres in Jurong 6. JURONG RAILWAY Hong Kah Village Chew Boon Lay and the Peng Kang area 7. PANDAN RESERVOIR SAFTI Former Jurong Town Hall 8. JURONG HILL Jurong Port Jurong Shipyard Jurong Fishery Port 9. JURONG PORT AND SHIPYARD The Jurong Railway Jurong and Singapore’s waste management 10. -

Section Training

NINE SECTION TRAINING I. SETTLING DOWN The only break at the end of basic training was the normal weekend, which was not much since the POP was on Saturday, 13th August and section training began on Monday, 15th August. There was no change to the configuration of the platoons and sections. Strictly speaking, each trainee was now a private soldier, but for some reason they were usually referred to as ‘trainees’, probably a force of habit. By now, however, the trainees had settled down to life at SAFTI and nearly everyone took the regimented routine in his stride. Friendships and loyalties had developed and housekeeping duties had sort of synchro-meshed. Collective punishment, especially extra-drill and the threat of confinement, had made it in every trainee’s interest to cover his barrack-mates and present a united front against the instructors. Physical fitness had reduced the stresses of life and improved reactions to the unexpected. A perceptible hardening had taken place in the last two months, and recovery from the previous day’s exertions was usually complete after a night’s deep sleep, even when it was brief because of late training. The sense of being constantly hassled was being replaced by a can-do spirit: the instructors had become to some extent predictable and pre-emptable. Besides, less ‘mistakes’ were being made. One of the most significant and welcome changes was that the trainees no longer had to move as platoons to and from the dining halls (exclusive to each company), but instead, went on their own or in random groups during the scheduled times. -

NHB Jurong Trail Booklet Cover R5.Ai

Introduction p. 2 Jurong Bird Park (p. 64) ship berths and handled a diverse range of cargo including metals, Masjid Hasanah (p. 68) SAFTI (p. 51) Early History 2 Jurong Hill raw sugar, industrial chemicals and timber. The port is not open for 492 Teban Gardens Road 500 Upper Jurong Road public access. Historical extent of Jurong Jurong Railway (p. 58) The Orang Laut and Selat Samulun A remaining track can be found at Ulu Pandan Park Connector, Early accounts of Jurong between Clementi Ave 4 and 6 The gambier pioneers: opening up the interior Evolution of land use in Jurong Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, the Singapore Armed Growth of communities p. 18 Forces Training Institute (SAFTI) was established to provide formal training for officers to lead its armed forces. Formerly located at Pasir Villages and social life Laba Camp, the institute moved to its current premises in 1995. Navigating Jurong One of the most-loved places in Jurong, the Jurong Bird Park is the Following the resettlement of villagers from Jurong’s surrounding largest avian park in the Asia Pacific region with over 400 species islands in the 1960s, Masjid Hasanah was built to replace the old Science Centre Singapore (p. 67) Beginnings of industry of birds. suraus (small prayer houses) of the islands. With community 15 Science Centre Road Early educational institutions support, the mosque was rebuilt and reopened in 1996. Jurong Fishery Port (p. 57) Fishery Port Road Opened in 1966, Jurong Railway was another means to transport Nanyang University (p. 28) Tide of change: World War II p. -

974 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

974 bus time schedule & line map 974 Joo Koon Int View In Website Mode The 974 bus line Joo Koon Int has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Joo Koon Int: 5:45 AM - 10:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 974 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 974 bus arriving. Direction: Joo Koon Int 974 bus Time Schedule 48 stops Joo Koon Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:45 AM - 10:45 PM Monday 5:45 AM - 10:45 PM Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009) 1 Joon Koon Circle, Singapore Tuesday 5:45 AM - 10:45 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079) Wednesday 5:45 AM - 10:45 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069) Thursday 5:45 AM - 10:45 PM Friday 5:45 AM - 10:45 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059) Saturday 5:45 AM - 10:45 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Jurong Camp (23049) Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Jurong West St 93 (22471) Pioneer Rd Nth - Opp Blk 653b (22461) 974 bus Info 988C Jurong West Street 93, Singapore Direction: Joo Koon Int Stops: 48 Jurong West St 63 - Pioneer Stn Exit B (22529) Trip Duration: 90 min 31 Jurong West Street 63, Singapore Line Summary: Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009), Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079), Jurong West St 63 - Blk 608 (22519) Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069), Upp Jurong West Street 63, Singapore Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059), Upp Jurong Rd - Jurong Camp (23049), Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Jurong West St 63 - Blk 664c (22509) Jurong West St 93 (22471), Pioneer Rd Nth - Opp Blk 664C Jurong West Street 64, Singapore 653b (22461), -

Route Integration

ROUTE INTEGRATION 256 & From Sunday, 18 June 2017 258 Opening of Tuas West MRT Extension 路线路线路线合并从路线 合并从合并从201720172017年年年年6666月月月月18181818日日日日起起起起 Laluan Bas Bersepadu Dari 18 Jun 2017 Skipped Bus Stops 18 ஜூ 2017 பயணேசைவக ஒகிைண ROAD NAME BUS STOP DESCRIPTION BUS STOP NO. Joo Koon – Jurong West Street 64 (Loop) SAFTI MILITARY INST 23079 BEF KIAN TECK RD 23069 • Service 256 will be integrated into Service 258. The amended Service 258 AFT KIAN TECK RD 23059 will ply between Joo Koon Interchange and Jurong West Street 64 (loop) JURONG CAMP 23049 via Jalan Ahmad Ibrahim and Jurong West Street 81 UPP BEF JURONG WEST ST 93 22471 • Skipped sector along Jurong West Street 62 (formerly served by Service JURONG RD AFT JURONG WEST ST 93 22479 256) and Upper Jurong Road (formerly served by Service 258) will be OPP JURONG CAMP 23041 served by Service 192 BEF KIAN TECK RD 23051 • Commuters travelling towards Joo Koon Interchange, can board at the bus AFT KIAN TECK RD 23061 stop 22499 along Jurong West Street 64, Opp Blk 662C OPP SAFTI MILITARY INST 23071 256号与258号巴士路线将合并。合并后的新258号巴士,将穿行于裕群转换 JURONG • BOON LAY INT 22009 站和裕廊西64街(环道)之间,途径惹兰阿末依布拉欣和裕廊西81街 WEST CTRL 3 • 原为256号巴士路线的裕廊西62街,以及原为258号巴士路线的裕廊路上段, OPP BLK662 22241 将由192号巴士取代 JURONG BLK622 22249 • 前往裕群转换站的乘客,可在裕廊西64街第662C座组屋对面的22499号巴士 WEST ST 62 BLK 665A 22251 站搭车 BLK 668D 22259 • Khidmat bas 256 akan disepadukan dengan khidmat bas 258. Khidmat bas bersepadu 258 akan berulang-alik di antara Pusat Pertukaran Bas Joo Koon dan Jurong West Street 64 melalui Jalan Ahmad Ibrahim dan Jurong West Street 81. • Sektor yang dilepasi sepanjang Jurong West Street 62 (sebelum ini dilalui khidmat bas 256) dan Upper Jurong Road (sebelum ini dilalui khidmat bas 258) akan digantikan oleh khidmat bas 192 • Penumpang menuju ke arah Pusat Pertukaran Bas Joo Koon boleh menaiki bas di perhentian bas 22499 sepanjang Jurong West Street 64, bertentangan Blok 662C • ேசைவ 256 ேசைவ 258-உட ஒகிைணகப. -

192 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

192 bus time schedule & line map 192 Boon Lay Int View In Website Mode The 192 bus line (Boon Lay Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Boon Lay Int: 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM (2) Tuas Ter: 5:45 AM - 11:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 192 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 192 bus arriving. Direction: Boon Lay Int 192 bus Time Schedule 33 stops Boon Lay Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM Tuas West Dr - Tuas Ter (25009) 3 Tuas West Road, Singapore Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM Tuas West Dr - Opp Tuas Link Stn (25421) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM Tuas West Dr - Super Continental (25431) Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM 21 Tuas West Drive, Singapore Friday 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM Tuas West Dr - Bef Pioneer Rd (25441) Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM 31 Tuas West Drive, Singapore Pioneer Rd - Bef Tuas West Ave (25681) 122 Pioneer Road, Singapore 192 bus Info Pioneer Rd - Tuas West Rd Stn Exit B (24711) Direction: Boon Lay Int 131 Pioneer Road, Singapore Stops: 33 Trip Duration: 45 min Tuas Ave 12 - Michelman (25511) Line Summary: Tuas West Dr - Tuas Ter (25009), 2A Tuas Avenue 12, Singapore Tuas West Dr - Opp Tuas Link Stn (25421), Tuas West Dr - Super Continental (25431), Tuas West Dr - Bef Tuas Ave 12 - Siem Seng Hing (25811) Pioneer Rd (25441), Pioneer Rd - Bef Tuas West Ave 8A Tuas Avenue 12, Singapore (25681), Pioneer Rd - Tuas West Rd Stn Exit B (24711), Tuas Ave 12 - Michelman (25511), Tuas Ave Tuas Ave 12 - Aft Tuas Ave 7 (25091) 12 -

National Day Awards 2020

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2020 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Prof S Jayakumar Senior Legal Adviser to the Minister for Foreign Affairs 1 2 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Koh Choon Hui Chairman, Singapore Children’s Society 2 Prof Wang Gungwu Former Chairman, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute Former Chairman, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore Former Chairman, East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore 2 3 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Chan Lai Fung Permanent Secretary (National Research & Development) Permanent Secretary (Public Sector Science and Technology Policy and Plans Office) Chairman, A*STAR 2 Assoc Prof Benjamin Ong Kian Chung Immediate Past Director of Medical Services 3 4 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Aljunied GRC 1 Mr Tng Kay Lim, BBM Chairman, Paya Lebar CCC Bishan-Toa Payoh GRC 2 Mr Roland Ng San Tiong, JP, BBM Chairman, Toa Payoh Central CCC East Coast GRC 3 Mdm Susan Ang Siew Lian, BBM Treasurer, Changi Simei CCC Holland-Bukit Timah GRC 4 Mr Lim Cheng Eng, BBM Patron, Bukit Timah CCMC Jurong GRC 5 Mr Richard Ong Chuan Huat, BBM Chairman, Bukit Batok East CCC 6 Mr Victor Liew Cheng San, BBM Vice-Chairman, Taman Jurong CCC Marine Parade GRC 7 Mr Ong Pang Aik, BBM Patron, Braddell Heights CCMC Sembawang GRC 8 Mr Norman Aw Kai Aik, BBM Chairman, Canberra -

Map of Planning Areas/Subzones in Singapore

The Senoko North Wharves Johor Sembawang Straits Sembawang North Senoko South North Tanjong Coast Admiralty Senoko Irau West Simpang Johor Greenwood Park Sembawang North Sembawang East Johor Central P. Seletar Woodlands Sembawang Pulau Midview East Springs Seletar Woodlands West Woodlands Northland Regional Centre Simpang South Kranji Yishun Woodlands West Reservoir Woodgrove Lim South Yishun P. Punggol Barat View Mandai Mandai Yishun Chu Kang East Pulau East Estate Central Punggol Barat P. Punggol Timor Turf Club Pulau Mandai Khatib Punggol West Yishun Timor Northshore North-Eastern South Islands Pang Sua Seletar Pulau Ubin Aerospace Seletar Lower Park Punggol Town Centre Coney Island Nee Soon Seletar Punggol Canal Pulau Tekong Matilda Springleaf Yew Tee Gali Waterway Batu East Fernvale Sengkang Anchorvale Punggol West P. Ketam Yio Chu Field Choa Chu K ang North Kang North Sengkang Town Changi Centre Pasir Ris Point Choa Rivervale Chu Kang Central Senja Saujana Tagore Yio Chu Wafer Fajar Compassvale Fab Park Teck Kang Yio Chu Seletar Western Water Whye Yio Chu Kang East Hills Lorong Catchment Trafalgar Halus Kang West Pasir Ris North Peng Siang West Pasir Ris Bangkit Hougang Park Loyang Jelebu Sembawang Changi Keat Hong Kebun Ang Mo Kio Serangoon Hougang East West Hills West Bahru Town Centre Cheng North Ind Serangoon West Paya Paya Central Water Catchment San Estate North Lebar Lebar Pasir Ris Dairy Hougang Lorong West North Central Gombak Farm Central Pasir Ris Shangri-la Halus Loyang Kangkar Drive Serangoon Garden Tampines East Townsville