Digestive Hemorrhaging in a Patient Being Treated with Anticoagulants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Approach to Thrombosis Prevention Across the Spectrum of Philadelphia-Negative Classic Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

Review The Approach to Thrombosis Prevention across the Spectrum of Philadelphia-Negative Classic Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Steffen Koschmieder Department of Medicine (Hematology, Oncology, Hemostaseology, and Stem Cell Transplantation), Faculty of Medicine, RWTH Aachen University, Pauwelsstr. 30, D-52074 Aachen, Germany; [email protected]; Tel.: +49-241-8080981; Fax: +49-241-8082449 Abstract: Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) are potentially facing diminished life expectancy and decreased quality of life, due to thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications, progression to myelofibrosis or acute leukemia with ensuing signs of hematopoietic insufficiency, and disturbing symptoms such as pruritus, night sweats, and bone pain. In patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) or polycythemia vera (PV), current guidelines recommend both primary and secondary measures to prevent thrombosis. These include acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) for patients with intermediate- or high-risk ET and all patients with PV, unless they have contraindications for ASA use, and phlebotomy for all PV patients. A target hematocrit level below 45% is demonstrated to be associated with decreased cardiovascular events in PV. In addition, cytoreductive therapy is shown to reduce the rate of thrombotic complications in high-risk ET and high-risk PV patients. In patients with prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis (pre-PMF), similar measures are recommended as in those with ET. Patients with overt PMF may be at increased risk of bleeding and thus require a more individualized approach to thrombosis prevention. This review summarizes the thrombotic Citation: Koschmieder, S. The risk factors and primary and secondary preventive measures against thrombosis in MPN. Approach to Thrombosis Prevention across the Spectrum of Keywords: myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN); polycythemia vera (PV); essential thrombocythemia Philadelphia-Negative Classic (ET); primary myelofibrosis (PMF); thrombosis; prevention; antiplatelet agents; anticoagulation; cy- Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. -

Factor V Leiden Thrombophilia

Factor V Leiden thrombophilia Description Factor V Leiden thrombophilia is an inherited disorder of blood clotting. Factor V Leiden is the name of a specific gene mutation that results in thrombophilia, which is an increased tendency to form abnormal blood clots that can block blood vessels. People with factor V Leiden thrombophilia have a higher than average risk of developing a type of blood clot called a deep venous thrombosis (DVT). DVTs occur most often in the legs, although they can also occur in other parts of the body, including the brain, eyes, liver, and kidneys. Factor V Leiden thrombophilia also increases the risk that clots will break away from their original site and travel through the bloodstream. These clots can lodge in the lungs, where they are known as pulmonary emboli. Although factor V Leiden thrombophilia increases the risk of blood clots, only about 10 percent of individuals with the factor V Leiden mutation ever develop abnormal clots. The factor V Leiden mutation is associated with a slightly increased risk of pregnancy loss (miscarriage). Women with this mutation are two to three times more likely to have multiple (recurrent) miscarriages or a pregnancy loss during the second or third trimester. Some research suggests that the factor V Leiden mutation may also increase the risk of other complications during pregnancy, including pregnancy-induced high blood pressure (preeclampsia), slow fetal growth, and early separation of the placenta from the uterine wall (placental abruption). However, the association between the factor V Leiden mutation and these complications has not been confirmed. Most women with factor V Leiden thrombophilia have normal pregnancies. -

Factor V Leiden Thrombophilia Jody Lynn Kujovich, MD

GENETEST REVIEW Genetics in Medicine Factor V Leiden thrombophilia Jody Lynn Kujovich, MD TABLE OF CONTENTS Pathogenic mechanisms and molecular basis.................................................2 Obesity ...........................................................................................................8 Prevalence..............................................................................................................2 Surgery...........................................................................................................8 Diagnosis................................................................................................................2 Thrombosis not convincingly associated with Factor V Leiden....................8 Clinical diagnosis..............................................................................................2 Arterial thrombosis...........................................................................................8 Testing................................................................................................................2 Myocardial infarction.......................................................................................8 Indications for testing......................................................................................3 Stroke .................................................................................................................8 Natural history and clinical manifestations......................................................3 Genotype-phenotype -

Prevalence of Genetic Thrombophilia in Primary Antiphospholipid Syndrome

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2021; 25: 3645-3646 Prevalence of genetic thrombophilia in primary antiphospholipid syndrome Dear Editor, Primary antiphospholipid syndrome (pAPS) is characterized by thrombotic events and preg- nancy losses associated with the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. The combination of two or more thrombophilic factors increases the risk of thrombosis1-5. The present study aimed to assess the prevalence of other genetic or acquired thrombophilic factors in pAPS and verify whether there is a relevant clinical association. We investigated a cohort of 62 patients (88.9% women; mean age: 39.3 years) diagnosed with pAPS (Sapporo criteria), the presence of other thrombophilic factors, namely: hyperhomocysteinemia (HH) by chemiluminescence method; protein S deficiency (DPS) through functional quantification by chronometric method; protein C (DPC) and antithrombin III (ATIII) deficiencies through functional quantification by the chromo- genic substrate; and the search for the G20210A mutation of the prothrombin gene (MGP) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), followed by digestion with Hind III restriction enzyme and the search for the Q506 mutation of the factor V gene (Leiden factor V - LFV), by PCR followed by digestion with restriction enzyme Mnl I. Three (19%) patients with LFVL in heterozygous form were found in 16 surveyed. HH was found in 2/40 (5%); 1/31 FVDATIII (3.2%); DPC at 7/33 (21%); and DPS at 8/32 (32%). No MGP was found in the 14 patients in which it was searched. It was also found that when comparing the groups of isolated APS with those of combined APS with thrombophilia factors, it was found that the age of the first presentation of thrombosis or pregnancy loss was significantly lower in the isolated APS group (30.4 vs. -

Risk of Gastrointestinal Bleed and Endoscopic Procedures on Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Agents Partha Pal, Manu Tandan, Duvvuru Nageshwar Reddy

Published online: 2019-09-16 Review Article Risk of Gastrointestinal Bleed and Endoscopic Procedures on Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Agents Partha Pal, Manu Tandan, Duvvuru Nageshwar Reddy Department of Medical The use of antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents has increased hand in hand with Gastroenterology, Asian the number and complexity of endoscopic procedures. Hence, the endoscopists Institute of Gastroenterology, Hyderabad, Telangana, India are often faced with considering endoscopy in patients on these agents. In this setting, to make informed decision, four key aspects are need to be considered. Abstract The type of antithrombotic or antiplatelet agent used and its characteristics, risk of thromboembolic events (which can lead to ischemic stroke or acute coronary syndrome, both of which carry high morbidity) due to withholding the drug, risk of bleeding (increases with invasiveness of procedure), and timing of procedure (elective or urgent) are the key factors to consider. We aim to discuss the risk of gastrointestinal bleed and endoscopic procedures on antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents focusing on Indian context based on recent Asia‑pacific guidelines along with other existing guidelines. Keywords: Antiplatelets, antithrombotic agents, endoscopy, gastrointestinal bleeding Introduction is taking. The knowledge of mechanism of action, astrointestinal (GI) bleed is one of the most onset and offset of action, pharmacokinetics, drug common medical emergencies in day‑to‑day interactions, and risk of bleeding with each agent is G essential for periendoscopic management of patients practice. With increase in age and comorbidities, on antiplatelet or antithrombotic agents. The timing of the use of antithrombotic agents (antiplatelet and discontinuation before endoscopy and resumption after anticoagulant agents) is widely prevalent, and this endoscopic hemostasis is discussed in detail later in the has added an additional dimension in the management manuscript. -

Congenital Thrombophilia

Congenital thrombophilia The term congenital thrombophilia covers a range of Factor V Leiden and pregnancy conditions that are inherited by someone at birth. This means It is important that women with Factor V Leiden who are that their blood is sticker than normal, which increases the pregnant discuss this with their obstetrician as they have an risk of blood clots and thrombosis. increased risk of venous thrombosis during pregnancy. Some Factor V Leiden and Prothrombin 20210 are the most evidence suggests that they may also have a slightly higher common thrombophilias among people of European origin. risk of miscarriage and placental problems. Other congenital thrombophilias include Protein C Deficiency, Protein S Deficiency, and Antithrombin Deficiency. Prothrombin 20210 Prothrombin is one of the blood clotting factors. It circulates Factor V Leiden in the blood and when activated, is converted to thrombin. Factor V Leiden is by far the most common congenital Thrombin causes fibrinogen, another clotting factor, to thrombophilia. In the UK it is present in 1 in 20 individuals of convert to fibrin strands, which make up part of a clot. European origin. It is rare in people of Black or Asian origin. The condition known as Prothrombin 20210 is due to a Factor V Leiden is caused by a change in the gene for Factor mutation of the prothrombin gene. Individuals with the V, which helps the blood to clot. To stop a clot spreading a condition tend to have slightly stickier blood, due to higher natural blood thinner, known as Protein C, breaks down prothrombin levels. Factor V. -

Rare Thrombophilic Conditions

342 Review Article Page 1 of 10 Rare thrombophilic conditions Gian Luca Salvagno1, Chiara Pavan2, Giuseppe Lippi1 1Section of Clinical Biochemistry, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; 2Division of Geriatric Medicine, Mater Salutis Hospital, Legnago, Verona, Italy Contributions: (I) Conception and design: GL Salvagno; (II) Administrative support: None; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: None; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: GL Salvagno, C Pavan; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Prof. Gian Luca Salvagno, MD, PhD. Sezione di Biochimica Clinica, Dipartimento di Neuroscienze, Biomedicina e Movimento, Università degli Studi di Verona, Ospedale Policlinico G.B. Rossi, Piazzale Scuro, 10, 37134 Verona, Italy. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Thrombophilia, either acquired or inherited, can be defined as a predisposition to developing thromboembolic complications. Since the discovery of antithrombin deficiency in the 1965, many other conditions have been described so far, which have then allowed to currently detect an inherited or acquired predisposition in approximately 60–70% of patients with thromboembolic disorders. These prothrombotic risk factors mainly include qualitative or quantitative defects of endogenous coagulation factor inhibitors, increased concentration or function of clotting proteins, defects in the fibrinolytic system, impaired platelet function, and hyperhomocysteinemia. In this review article, we aim to provide an overview on epidemiologic, clinic and laboratory aspects of both acquired and inherited rare thrombophilic risk factors, especially including dysfibrinogenemia, heparin cofactor II, thrombomodulin, lipoprotein(a), sticky platelet syndrome, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 apolipoprotein E, tissue factor pathway inhibitor, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. -

Thrombocytopenia and Intracranial Venous Sinus Thrombosis After “COVID-19 Vaccine Astrazeneca” Exposure

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Thrombocytopenia and Intracranial Venous Sinus Thrombosis after “COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca” Exposure Marc E. Wolf 1,2 , Beate Luz 3, Ludwig Niehaus 4 , Pervinder Bhogal 5, Hansjörg Bäzner 1,2 and Hans Henkes 6,7,* 1 Neurologische Klinik, Klinikum Stuttgart, D-70174 Stuttgart, Germany; [email protected] (M.E.W.); [email protected] (H.B.) 2 Department of Neurology, Universitätsmedizin Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, D-68167 Mannheim, Germany 3 Zentralinstitut für Transfusionsmedizin und Blutspendedienst, Klinikum Stuttgart, D-70174 Stuttgart, Germany; [email protected] 4 Neurologie, Rems-Murr-Klinikum Winnenden, D-71364 Winnenden, Germany; [email protected] 5 Department of Interventional Neuroradiology, The Royal London Hospital, Barts NHS Trust, London E1 1FR, UK; [email protected] 6 Neuroradiologische Klinik, Klinikum Stuttgart, D-70174 Stuttgart, Germany 7 Medical Faculty, University Duisburg-Essen, D-47057 Duisburg, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Fax: +49-711-278-345-09 Abstract: Background: As of 8 April 2021, a total of 2.9 million people have died with or from the coronavirus infection causing COVID-19 (Corona Virus Disease 2019). On 29 January 2021, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved a COVID-19 vaccine developed by Oxford University Citation: Wolf, M.E.; Luz, B.; and AstraZeneca (AZD1222, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, COVID-19 vaccine AstraZeneca, Vaxzevria, Cov- Niehaus, L.; Bhogal, P.; Bäzner, H.; ishield). While the vaccine prevents severe course of and death from COVID-19, the observation of Henkes, H. Thrombocytopenia and pulmonary, abdominal, and intracranial venous thromboembolic events has raised concerns. Objec- Intracranial Venous Sinus Thrombosis after “COVID-19 Vaccine tive: To describe the clinical manifestations and the concerning management of patients with cranial AstraZeneca” Exposure. -

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Coagulation Disorders Carl-Erik Dempfle

Disseminated intravascular coagulation and coagulation disorders Carl-Erik Dempfle Purpose of review Abbreviations An update on recent developments in diagnosis and treatment aPTT activated partial thromboplastin time of disseminated intravascular coagulation. DAA drotrecogin a (activated) DIC disseminated intravascular coagulation Recent findings FRM fibrin-related marker Disseminated intravascular coagulation is defined as a typical ISTH International Society for Thrombosis and Hemostasis disease condition with laboratory findings indicating massive # coagulation activation and reduction in procoagulant capacity. 2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 0952-7907 Clinical syndromes associated with the condition are consumption coagulopathy, sepsis-induced purpura fulminans, and viral hemorrhagic fevers. Consumption coagulopathy is Introduction observed in patients with sepsis, aortic aneurysms, acute The diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation promyelocytic leukemia, and other disseminated malignancies. (DIC) is based on the combination of a disease condition Sepsis-induced purpura fulminans is characterized by with laboratory findings indicating massive coagulation microvascular occlusion causing hemorrhagic necrosis of the activation and reduction in procoagulant capacity (Table skin and organ failure. Viral hemorrhagic fevers result in 1). Current scoring systems include elevated fibrin- massively increased tissue factor production in monocytes and related markers (FRMs), prolonged prothrombin time, macrophages, inducing microvascular -

Essential Thrombocythemia

Essential thrombocythemia Seong Hyun Jeong, MD. Department of Hematology-Oncology Ajou University School of Medicine Contents • Introduction • Clinical features • Pathogenesis • Diagnosis • Management Q1. ET가 의심되는 Thrombocytosis환자에서 골수검사를 시행해야 하는 경우는? 1. JAK2 mutation test가 음성일 경우 2. JAK2 mutation과 상관 없이 모든환자에서 3. 다른 myeloid neoplasm을 의심할 수 있는 (splenomegaly, anemia, PB이상)소견이 있을때 4. 시행하지 않는다. Q2. Thombosis 과거력이 없는 60세 미만의 ET 환자에서 cytoreductive therapy를 시작해야 하는 경우는? 1. 혈소판이 정상수치 이상인 경우 2. Platelet > 1,000 x 109/L 3. Platelet > 1,500 x 109/L 4. 무증상이면 경과관찰 한다. Q3. 임신한 고위험군의 ET환자에서 처방이 가능한 약제는? a. Low dose aspirin b. Interferon-α c. Anagrelide d. Hydroxyurea 1. a 2. a, b 3. a, b, c 4. a, b, c, d 5. 모두 가능하지 않음 History • First recognized as a specific disease entity in 1934 under the term hemorrhagic thrombocythemia. - Characterized by thrombocytosis with bone marrow megakaryocytic hyperplasia and a tendency to develop vascular complications. • Placed within myeloproliferative disorders in 1951 by Dameshek. • Shown to be a clonal disorder in 1981. • Discovery of an acquired mutation in the JAK2 gene in 2005. William Damshek (1900-1969) WHO (2008) classification of the MPNs Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) Chronic myelogenous leukemia, BCR-ABL1-positive Chronic neutrophilic leukemia Polycythemia vera Primary myelofibrosis Essential thrombocythemia Chronic eosinophilic leukemia, not otherwise specified Mastocytosis Myeloproliferative neoplasms, unclassifiable Vardiman et al. Blood. 2009;114:937-51 Clinical features • ET is the most common of the Philadelphia chromosome negative MPN. • The annual incidence 1-2.5/100,000 with female predominance. • May present at any age, peak incidence between age of 50 and 70 years. -

Thrombophilia

GACETA MÉDICA DE MÉXICO EDITORIAL Thrombophilia Abraham Majluf-Cruz Unit of Medical Research on Thrombosis, Hemostasis and Atherogenesis, Hospital General Regional Carlos MacGregor Sánchez Navarro, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Ciudad de México, Mexico The coagulation system maintains blood in a fluid vision. This is one of the fundamental reasons why, state at every moment and, therefore, it is unceasingly rather frequently, we exaggerate blood losses, which active throughout life. However, at the moment a le- drives us to misuse blood and its derivatives, or to sion of the vascular system occurs, the coagulation make absurd or unnecessary decisions, such as call- system immediately turns 180° and transforms blood ing off surgeries or invasive diagnostic procedures. into a perfectly localized solid body, which we call clot. The questions then are: Why does the possibility or This process, by means of which a clot is formed, is the presence of hemorrhage affect us that much? Why known as hemostasis, which is one of the compo- is it that doctors, even after having been trained as nents of the coagulation system1. such, do not escape this connotation imprinted on The workup of a patient with a coagulation system human being’s collective memory? Why, if thrombosis abnormality is really very simple. All the patient’s al- is much more deleterious on human beings, we still terations are classified into two general types: either fail to give it its rightful place? I think the answer is the patient suffers a hemorrhage or has a thrombosis. very simple. Hemorrhage can be seen, and this im- There is nothing else. -

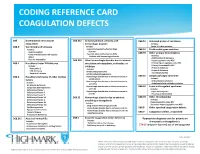

Coding Reference Card Coagulation Defects

CODING REFERENCE CARD COAGULATION DEFECTS D65 Disseminated intravascular D68.312 Antiphospholipid antibody with D68.51 Activated protein C resistance coagulation hemorrhagic disorder Includes: D68.0 Von Willebrand’s Disease Includes: Factor V Leiden mutation Includes: Lupus anticoagulant w/hemorrhagic D68.52 Prothrombin gene mutation Angiohemophilia disorder D68.59 Other primary thrombophilia Factor VIII deficiency with vascular Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Inhibitor with hemorrhagic disorder Includes: defect Antithrombin III deficiency Vascular hemophilia D68.318 Other hemorrhagic disorder due to intrinsic Hypercoagulable state NOS D68.1 Hereditary Factor XI Deficiency circulation anticoagulants, antibodies, or Primary hypercoagulable state NEC Includes: inhibitors Primary thrombophilia NEC Protein C deficiency Hemophilia C Includes: Protein S deficiency PTA deficiency Antithromboplastinemia Thrombophilia NOS Rosenthal’s disease Antithromboplastinogenemia D68.2 Hereditary Deficiency of other clotting Hemorrhagic disorder due to intrinsic increase in D68.61 Antiphospholipid syndrome Includes: factors antithrombin Hemorrhagic disorder due to intrinsic increase in Anticardiolipin syndrome Includes: anti-VIIIa Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome AC globulin deficiency Hemorrhagic disorder due to intrinsic increase in D68.62 Lupus anticoagulant syndrome Congenital afibrinogenemia anti- iXa Includes: Deficiency of factor I Hemorrhagic disorder due to intrinsic increase in Lupus anticoagulant Deficiency of factor II anti-XIa Presence of