Antechinus Stuartii)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Phascogale Calura) Corinne Letendre, Ethan Sawyer, Lauren J

Letendre et al. BMC Zoology (2018) 3:10 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-018-0036-3 BMC Zoology RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Immunosenescence in a captive semelparous marsupial, the red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura) Corinne Letendre, Ethan Sawyer, Lauren J. Young and Julie M. Old* Abstract Background: The red-tailed phascogale is a ‘Near Threatened’ dasyurid marsupial. Males are semelparous and die off shortly after the breeding season in the wild due to a stress-related syndrome, which has many physiological and immunological repercussions. In captivity, males survive for more than 2 years but become infertile after their first breeding season. Meanwhile, females can breed for many years. This suggests that captive males develop similar endocrine changes as their wild counterparts and undergo accelerated aging. However, this remains to be confirmed. The health status and immune function of this species in captivity have also yet to be characterized. Results: Through an integrative approach combining post-mortem examinations, blood biochemical and hematological analyses, we investigated the physiological and health status of captive phascogales before, during, and after the breeding season. Adult males showed only mild lesions compatible with an endocrine disorder. Both sexes globally maintained a good body condition throughout their lives, most likely due to a high quality diet. However, biochemistry changes potentially compatible with an early onset of renal or hepatic insufficiency were detected in older individuals. Masses and possible hypocalcemia were observed anecdotally in old females. With this increased knowledge of the physiological status of captive phascogales, interpretation of their immune profile at different age stages was then attempted. -

What Role Does Ecological Research Play in Managing Biodiversity in Protected Areas? Australia’S Oldest National Park As a Case Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online What Role Does Ecological Research Play in Managing Biodiversity in Protected Areas? Australia’s Oldest National Park as a Case Study ROSS L. GOLDINGAY School of Environmental Science & Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2480 Published on 3 September 2012 at http://escholarship.library.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/LIN Goldingay, R.L. (2012). What role does ecological research play in managing biodiversity in protected areas? Australia’s oldest National Park as a case study. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 134, B119-B134. How we manage National Parks (protected areas or reserves) for their biodiversity is an issue of current debate. At the centre of this issue is the role of ecological research and its ability to guide reserve management. One may assume that ecological science has suffi cient theory and empirical evidence to offer a prescription of how reserves should be managed. I use Royal National Park (Royal NP) as a case study to examine how ecological science should be used to inform biodiversity conservation. Ecological research relating to reserve management can be: i) of generic application to reserve management, ii) specifi c to the reserve in which it is conducted, and iii) conducted elsewhere but be of relevance due to the circumstances (e.g. species) of another reserve. I outline how such research can be used to inform management actions within Royal NP. I also highlight three big challenges for biodiversity management in Royal NP: i) habitat connectivity, ii) habitat degradation and iii) fi re management. -

Ecology and Predator Associations of the Northern Quoll (Dasyurus Hallucatus) in the Pilbara Lorna Hernandez Santin M.Sc

Ecology and predator associations of the northern quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus) in the Pilbara Lorna Hernandez Santin M.Sc. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Biological Sciences Abstract The northern quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus) is an endangered carnivorous marsupial in the family Dasyuridae that occurs in the northern third of Australia. It has declined throughout its range, especially in open, lowland habitats. This led to the hypothesis that rocky outcrops where it persists provide a safe haven from introduced predators and provide greater microhabitat heterogeneity associated with higher prey availability. Proposed causes of decline include introduced cane toads (Rhinella marina, which are toxic), predation by feral cats (Felis catus), foxes (Vulpes vulpes), and the dingo (Canis lupus), and habitat alteration by changes in fire regimes. The National Recovery Plan highlighted knowledge gaps relevant to the conservation of the northern quoll. These include assembling data on ecology and population status, determining factors in survival, especially introduced predators, selecting areas that can be used as refuges, and identifying and securing key populations. The Pilbara region in Western Australia is a key population currently free of invasive cane toads (a major threat). The Pilbara is a semi-arid to arid area subject to cyclones between December and March. I selected two sites: Millstream Chichester National Park (2 381 km2) and Indee Station (1 623 km2). These are dominated by spinifex (hummock) grasslands, with rugged rock outcrops, shrublands, riparian areas, and some soft (tussock) grasslands. They are subject to frequent seasonal fires, creating a mosaic of recently burnt and longer unburnt areas. -

Vertebrate Fauna Survey Worimi Conservation Lands

VERTEBRATE FAUNA SURVEY WORIMI CONSERVATION LANDS FINAL REPORT Prepared for NSW DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE ECOTONE ECOLOGICAL CONSULTANTS Pty Ltd 39 Platt Street, Waratah NSW 2298 Phone: (02) 4968 4901 fax: (02) 4968 4960 E-mail: [email protected] EEC PROJECT No. 0583CW SEPTEMBER 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Worimi Conservation Lands (WCL) cover an area of 4,200 hectares and are made up of three reserves: Worimi National Park, Worimi State Conservation Area and Worimi Regional Park. The WCL have been identified as a significant cultural landscape and are co-managed by a board of management. A vertebrate fauna survey of the Worimi Conservation lands has been undertaken in order to identify the fauna species assemblages within the WCL and record any significant species, including threatened species. As most of the previous studies were situated outside of or on the periphery of the WCL, a more detailed assessment of the fauna communities and habitat would assist in the future management for the WCL. From the literature review a total of 270 fauna species (excluding marine mammals) have been recorded within the study locality (2 km from the centre line of the WCL). These consisted of 189 bird, 49 mammal, 17 reptile and 15 frog species. It should be pointed out that it is unlikely that all of these species would occur within the WCL as the search area provides a greater variety of habitats than those identified within the WCL. Prior to the current survey a total of 135 species had been recorded within or very close to the WCL boundary. -

Antechinus Housing and Care

Antechinus Housing and Care by Norma Henderson Yellow-footed Antechinus Antechinus flavipes Photo Tom Tarrant Yellow-footed Antechinus Antechinus flavipes This is the most widespread of the antechinuses and has a slate grey head grading to orange-brown on the sides, belly, rump and feet, white patches on the throat and belly and a pale ring around the eye and a black tail tip. The head is long and pointed with a black muzzle tip, bulging eyes and thin crinkled ears. The hind feet are broad. They have ridged pads on the underside of the feet which enable it to climb well and grip tightly as the run along the underside of branches. Their weigh ranges from 21-80 grams. Brown Antechinus Antechinus stuartii This antechinus is greyish brown above and paler below. It has a lightly haired tail, the same length as the body or shorter. The head is long with a pointed snout, long whiskers, fairly large ears with a notch in the margin, and attractive brown eyes. Their front teeth consist of four pairs of small sharp incisors. They have pads on the soles of their feet, which are climbing adaptions, and the first toe on the hind foot opposes the others. If food is scarce they can preserve energy by becoming torpid for a few hours at a time. Their weight ranges from 17-71g. Although these little creatures look similar to the feral mouse, there are obvious differences - they lack the pungent odours associated with mice, and they also lack the enlarged incisors (front teeth) of the mouse. -

17. Morphology and Physiology of the Metatheria

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 17. MORPHOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE METATHERIA T.J. DAWSON, E. FINCH, L. FREEDMAN, I.D. HUME, MARILYN B. RENFREE & P.D. TEMPLE-SMITH 1 17. MORPHOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE METATHERIA 2 17. MORPHOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE METATHERIA EXTERNAL CHARACTERISTICS The Metatheria, comprising a single order, Marsupialia, is a large and diverse group of animals and exhibits a considerable range of variation in external features. The variation found is intimately related to the animals' habits and, in most instances, parallels that are found in the Eutheria. Useful general references to external characteristics include Pocock (1921), Jones (1923a, 1924), Grassé (1955), Frith & Calaby (1969), Ride (1970) and Strahan (1983). Body form In size, the marsupials range upwards from the Long-tailed Planigale, Planigale ingrami, a small, mouse-like animal weighing only around 4.2 g, with a head- body length of 59 mm and a tail 55 mm long. At the other extreme, there are large kangaroos, such as the Red Kangaroo, Macropus rufus, in which the males may weigh as much as 85 kg and attain a head-body length of 1400 mm and a tail of 1000 mm. Body shape also varies greatly. The primarily carnivorous marsupials, the dasyurids (for example, antechinuses, dunnarts, quolls, planigales and others), are small to medium sized quadrupeds with subequal limbs. The tail is relatively slender and generally about half the length of the body. The omnivorous peramelids show increased development of the hind limbs in keeping with their rapid bounding locomotion. Saltatory or hopping forms (for example kangaroos and wallabies), carry the hind limb specialisation to an extreme, with a concomitant reduction of the forelimbs (Fig. -

Kultarr (Antechinomys Laniger)

Husbandry Guidelines for: Kultarr Antechinomys laniger Mammalia: Dasyuridae (Egerton, 2005) Complier: Teresa Attard Date of Preparation: 2009 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: Certificate III in Captive Animals, RUV30204 Lecturer: Graeme Phipps, Jacki Salkeld and Brad Walker DISCLAIMER This document is intended to be specifically treated as guidelines and a ‘work in progress’ in the care and husbandry of the kultarr (Antechinomys laniger). Any incident resulting from the misuse of this document will not be recognised as the responsibility of the author. Please use at the participants discretion. Any enhancements to this document to increase animal care standards and husbandry techniques are appreciated. 2 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS The kultarr is an innocuous species. Although they are capable of biting when stressed, it is unlikely they have the potential to break the skin. It is the carer’s responsibility to minimise stress to the animal when possible by limiting exposure to excess noise and predators, avoid invading the animals fright zone, providing adequate privacy and facilitating for natural behaviours. Potential occupational health and safety risks to the animal include the use of inappropriate sterilisation agents or at incorrect dilutions, crushing risk from enclosure furniture and inadequate housing arrangements that may adversely affect the animal’s health (e.g. extremes of temperature). They are ideally maintained in a controlled, secure environment of a nocturnal house where their behaviours and health can be monitored at minimal disturbance. Carers are advised to wear disposable gloves when cleaning enclosures and handling chemical products to minimise risk and to maintain high standards of hygiene. -

About Marsupials : a Guide for Children / Cathryn Sill ; Illustrated by John Sill

About Marsupials About Marsupials A Guide for Children Cathryn Sill Illustrated by John Sill For the One who created marsupials. —Genesis 1:25 About Marsupials Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2006 by Cathryn P. Sill Illustrations © 2006 by John C. Sill All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Illustrations created in watercolor on archival quality 100% rag watercolor paper Text and titles set in Novarese from Adobe Systems Printed in Singapore 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 (hardcover) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 (trade paperback) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sill, Cathryn P., 1953- About marsupials : a guide for children / Cathryn Sill ; illustrated by John Sill. p. cm ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-358-0 / ISBN 10: 1-56145-358-7 (hardcover) ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-407-5 / ISBN 10: 1-56145-407-9 (trade paperback) 1.. Marsupials--Juvenile literature. I. Sill, John, ill. II. Title. QL737.M3S55 2006 599.2--dc22 2005020582 Marsupials are mammals whose babies are born tiny and helpless. PLATE 1 Gray Kangaroo Most mother marsupials have a pouch on their bellies to keep the babies safe as they drink milk and grow. PLATE 2 Red-necked Wallaby The pouch of some marsupials opens toward the mother’s back legs. -

North Head Site Story

Overview of North Head North Head, a tied island formed approximately 90 million years ago, is the northern headland at the entrance to Sydney Harbour. Derived from Hawkesbury Sandstone and Newport formations, the headland is comprised of predominantly sandstone and shale, which support a mosaic of different vegetation types. This land is managed by National Parks and Wildlife Service, Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, Q Station, The Australian Institute of Police Management and the North Head Sewerage Treatment Plant, Northern Beaches Council and others. North Head is a national heritage site. Banksia aemula, a characteristic species of Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub (ESBS), with Leptospermum laevigatum dominated senescent Flora at North Head ESBS in the background. North Head is dominated by dense sclerophyllous vegetation, which comprises eight distinct bentwing bat (Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis).Two vegetation communities, including Coastal notable, and somewhat iconic, species that occur Sandstone Plateau Heath, Coastal Rock-plate at North Head are the long-nosed bandicoot Heath, Coastal Sandstone Ridgetop Woodland and (Perameles nasuta) and the little penguin the endangered Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub (Eudyptula minor), with both listed as threatened (ESBS). Characteristic species of plants within populations. these communities include the smooth-barked Several major threats to both flora and fauna occur apple (Angophora costata), red bloodwood (Corymbia at North Head. These include predation by gummifera), coastal tea tree (Leptospermum laevigatum), domestic and feral animals, vehicle strike heath-leaved banksia (Banksia ericifolia) and the (particularly bandicoots), fragmentation and loss of coastal banksia (Banksia integrifolia). A total of more habitat, weed infestation, inappropriate fire than 460 plant species have been recorded within regimes and stormwater runoff (increasing these communities so far, including the sunshine nutrients and the spread of weeds). -

Hollow Using Species List & Nest Box Designs for the East Gippsland

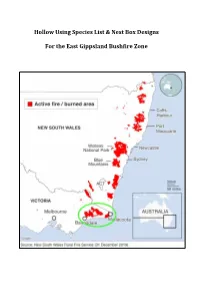

Hollow Using Species List & Nest Box Designs For the East Gippsland Bushfire Zone Purpose of this booklet Large areas of native forest have been burnt by bushfires during the 2019-20 bushfire season, from farm to coast across the Great Dividing Range. And the fires are burning still as I write this today on the 4th of January 2020. Millions of native animals have perished – from insects, lizards, birds, frogs, to mammals. For these huge ‘armageddon’ bushfire impacted regions to be recolonised, nearby populations of native wildlife will need to survive and thrive. There are over 300 native species in Australia using tree hollows for shelter and breeding, of which 114 species are birds, and 83 of these species are mammals. There will have been a significant loss of old hollow-bearing trees throughout the burnt zones. It is expected that some birds may have escaped the flames, but will be unable to breed in future years if they require tree hollows for nesting. Surviving nocturnal arboreal mammals will similarly struggle to find tree hollows to shelter in during the day. This booklet series has been compiled from existing online resources to enable volunteer nest box makers to quickly learn how to make nest boxes, for the species that occur within their region. I have collated the information in this booklet from the following organisations and resources: Birdlife Australia: https://birdlife.org.au/images/uploads/education_sheets/INFO- Nestbox-technical.pdf Birds in Backyards: http://www.birdsinbackyards.net/Nest-Box-Plans Greater Sydney -

Natural History of the Metatheria

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 18. NATURAL HISTORY OF THE METATHERIA ELEANOR M. RUSSELL, A.K. LEE & GEORGE R. WILSON 1 18. NATURAL HISTORY OF THE METATHERIA 2 18. NATURAL HISTORY OF THE METATHERIA NATURAL HISTORY Ecology Diet. Traditionally, Australian marsupials have been viewed in two dietary categories: the predominantly carnivorous marsupials, with polyprotodont dentition, and the predominantly herbivorous large diprotodonts. Recent observations on feeding (Smith 1982a; Henry & Craig 1984) and analysis of diet (Hall 1980a; Statham 1982) have not altered this view in the broadest sense. They have shown, however, that some polyprotodonts such as the peramelids (bandicoots) (Heinsohn 1966; Lee & Cockburn 1985) and the Bilby, Macrotis lagotis (Johnson 1980a), include significant proportions of plant items in their diets. Further, some small and medium-sized diprotodonts are now known to be dependent upon plant products such as nectar, pollen, plant exudates, fruit and seed (Smith 1982a; Mansergh 1984b; Turner 1984a, 1984b; Lee & Cockburn 1985). Arthropods appear to be the principal food items of most dasyurids (for example, Antechinus species, quolls, phascogales and planigales) (Morton 1978d; Blackall 1980; Hall 1980a; Statham 1982; Lee & Cockburn 1985), peramelids (Heinsohn 1966; Lee & Cockburn 1985), the Bilby (Johnson 1980a), the Marsupial Mole, Notoryctes typhlops (Corbett 1975), the Numbat, Myrmecobius fasciatus (Calaby 1960) and the Striped Possum, Dactylopsila trivirgata (Smith 1982b). Arthropods also are consistent, but not predominant, food items of burramyids (pygmy-possums) (Turner 1984a, 1984b), petaurids (ring-tail possums and gliders) (Smith 1982a, 1984a; Smith & Russell 1982) and occasionally occur in the diet of the Common Brushtail Possum, Trichosurus vulpecula (Kerle 1984c). Vertebrates appear to be important in the diet of some large dasyurids, although many feed predominantly upon insects (Blackall 1980; Godsell 1982).