Abc-Bulletin-Autumn-2014.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingston Lacy Illustrated List of Pictures K Introduction the Restoration

Kingston Lacy Illustrated list of pictures Introduction ingston Lacy has the distinction of being the however, is a set of portraits by Lely, painted at K gentry collection with the earliest recorded still the apogee of his ability, that is without surviving surviving nucleus – something that few collections rival anywhere outside the Royal Collection. Chiefly of any kind in the United Kingdom can boast. When of members of his own family, but also including Ralph – later Sir Ralph – Bankes (?1631–1677) first relations (No.16; Charles Brune of Athelhampton jotted down in his commonplace book, between (1630/1–?1703)), friends (No.2, Edmund Stafford May 1656 and the end of 1658, a note of ‘Pictures in of Buckinghamshire), and beauties of equivocal my Chamber att Grayes Inne’, consisting of a mere reputation (No.4, Elizabeth Trentham, Viscountess 15 of them, he can have had little idea that they Cullen (1640–1713)), they induced Sir Joshua would swell to the roughly 200 paintings that are Reynolds to declare, when he visited Kingston Hall at Kingston Lacy today. in 1762, that: ‘I never had fully appreciated Sir Peter That they have done so is due, above all, to two Lely till I had seen these portraits’. later collectors, Henry Bankes II, MP (1757–1834), Although Sir Ralph evidently collected other – and his son William John Bankes, MP (1786–1855), but largely minor pictures – as did his successors, and to the piety of successive members of the it was not until Henry Bankes II (1757–1834), who Bankes family in preserving these collections made the Grand Tour in 1778–80, and paid a further virtually intact, and ultimately leaving them, in the visit to Rome in 1782, that the family produced astonishingly munificent bequest by (Henry John) another true collector. -

National Trust Report

England will lose all historical buildings und beautiful nature places... AUDIO (I've already sendet it to Ms Suter (N.T.2)) Kingston Lacy Library in Kingston Lacy Souvenirs from Egypt ...if the National Trust wouldn't exist. In the time of global warming it is very important that somebody looks after beautiful places, otherwise these places will be lost. But also objects which aren't in danger because of global warming are endangered if nobody looks after them. The National Trust saves historical houses und nature reserves and restores them when needed. This charity is really important for England. That is why you should learn more about this organisation. In my post you will find a lot of information about the National Trust and you will see what people who live in England think about the National Trust. The National Trust Introduction When you make a journey through England and you visit special places or buildings you might see a board with information about this place. On this board you will often see the company logo of the National Trust which is a branch of maple leaves on a green background. When I visited London, I saw many such information boards. The National Trust supports for example Carlyleꞌ s House, the Eastbury Manor House and other tourist attractions. At the beginning of my project I knew that the National Trust does exist. But I wanted to know more about this charity. I wanted to find out whether my hypothesis: “The National Trust is very important for the environment and the historical buildings of England” is true or not. -

Find out More *Dogs Not Permitted at These Events

Events for autumn/winter 2019 Dorset / Gloucestershire / Somerset / Wiltshire Corfe Castle Father Christmas at Christmas at Arlington Court Find out more The selection of events here is a small part of what’s on offer. You can visit the events page of the website at ©National Trust Images/John Bish Images/John Trust ©National ©National Trust Images/Hannah Burton nationaltrust.org.uk/ Events near you whats-on and use the search function to for autumn & find out everything that’s going on winter 2019 near you, or at your favourite place. Key to How to book symbols Facilities and access information can We have indicated where there is an event charge and where booking is necessary. Please note that normal admission charges apply Half-term be found on each unless you are a member. All children must be accompanied by an place’s homepage adult. And please check beforehand as to whether or not dogs are Halloween on the website, as welcome. We do take every effort to ensure that all event details are can contact details if correct at the time of going to press. The National Trust reserves the Christmas right to cancel or change events if necessary. you require further Tickets are non-refundable. Father information. Christmas ©National Trust Images/John Millar New Year’s ramble Walk with an archaeologist BATH AND NORTH Sun 5 Jan, 9.30am-2pm BRISTOL Sat 16 Nov, 2-4pm On this fairly fast-paced guided walk of the Discover the secrets of Cadbury Camp Iron EAST SOMERSET Bath Skyline you may burn off some Age hill fort on this walk with archaeologist Christmas calories, but a diversion to Prior Leigh Woods Martin Papworth. -

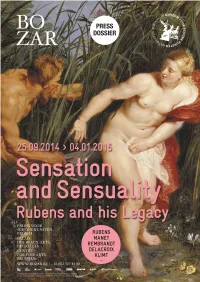

'Rubens and His Legacy' Exhibition in Focus Guide

Exhibition in Focus This guide is given out free to teachers and full-time students with an exhibition ticket and ID at the Learning Desk and is available to other visitors from the RA Shop at a cost of £5.50 (while stocks last). ‘Rubens I mention in this place, as I think him a remarkable instance of the same An Introduction to the Exhibition mind being seen in all the various parts of the art. […] [T]he facility with which he invented, the richness of his composition, the luxuriant harmony and brilliancy for Teachers and Students of his colouring, so dazzle the eye, that whilst his works continue before us we cannot help thinking that all his deficiencies are fully supplied.’ Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourse V, 10 December 1772 Introduction Written by Francesca Herrick During his lifetime, the Flemish master Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) For the Learning Department was the most celebrated artist in Europe and could count the English, French © Royal Academy of Arts and Spanish monarchies among his prestigious patrons. Hailed as ‘the prince of painters and painter of princes’, he was also a skilled diplomat, a highly knowledgeable art collector and a canny businessman. Few artists have managed to make such a powerful impact on both their contemporaries and on successive generations, and this exhibition seeks to demonstrate that his Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cézanne continued influence has had much to do with the richness of his repertoire. Its Main Galleries themes of poetry, elegance, power, compassion, violence and lust highlight the 24 January – 10 April 2015 diversity of Rubens’s remarkable range and also reflect the main topics that have fired the imagination of his successors over the past four centuries. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Civil War: Parliamentarians Vs Royalists (KS2-KS3)

BACK TO CONTENTS SELF-LED ACTIVITY CIVIL WAR: PARLIAMENTARIANS VS ROYALISTS KS2 KS3 Recommended for SUMMARY KS2–3 (History, English) This activity will explore the backgrounds, beliefs and perspectives of key people in the English Civil War to help the class gain a deeper understanding of the conflict. In small groups of about three, ask Learning objectives students to read the points of view of the six historical figures on • Learn about the different pages 33 and 34. They should decide whether they think each person figures leading up to the was a Royalist or a Parliamentarian, and why; answers can be found English Civil War and their in the Teachers’ Notes on page 32. Now conduct a class discussion perspectives on the conflict. about the points made by each figure and allow for personal thoughts • Understand the ideologies and responses. Collect these thoughts in a collaborative mind map. of the different sides in the Next, divide the class into ‘Parliamentarians’ and ‘Royalists’. Using the English Civil War. historical figures’ perspectives on pages 33 and 34, the points the • Use historical sources to class made, and the tips below, have the students prepare a speech to formulate a classroom persuade those in the other groups to join them. debate. Invite two students from each side to present their arguments; after both sides have spoken, discuss how effective their arguments were. Time to complete The Parliamentarians and the Royalists could not reach an agreement and so civil war broke out – is the group able to reach a compromise? Approx. 60 minutes TOP TIPS FOR PERSUASIVE WRITING Strong arguments follow a clear structure. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Imaging the Egyptian Obelisk at Kingston Lacy

Imaging the Egyptian Obelisk at Kingston Lacy Lindsay MacDonald Jane Masséglia Charles Crowther Faculty of Engineering Department of Classics Department of Classics University College London Oxford University Oxford University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ben Altshuler Sarah Norodom Andrew Cuffley Department of Classics Department of Classics GOM UK Limited Oxford University Oxford University Coventry [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] James Grasby South-West Region The National Trust [email protected] The obelisk that stands in the grounds of the National Trust property at Kingston Lacy, Dorset, was brought from Egypt in 1821 by William John Bankes. Known as the Philae obelisk, it has hieroglyphic inscriptions on the tapered granite column and Greek on the pedestal. In a multidisciplinary project to mark the success of the Philae comet mission, the inscriptions have been digitised by both reflectance transform imaging and 3D scanning. Novel imaging techniques have been developed to stitch together the separate RTI fields into a composite RTI for each face of the obelisk in registration with the geometric structure represented by the 3D point cloud. This will provide the basis for both paleographic examination of the inscriptions and visualisation of the monument as a whole. Keywords: Digital archaeology, reflectance transform imaging, 3D scanning, palaeography, monument 1. HISTORY OF THE OBELISK Travelling up the Nile, the island of Philae (on the ancient border of Egypt and Nubia) fascinated Kingston Lacy has one of the earliest collections Bankes, as the beauty of its temples had similarly of Egyptian artefacts in Britain, including the 6.7m captivated other European visitors. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Sir Roger Pratt's Library

Reading as a Gentleman and an Architect: Sir Roger Pratt’s Library by KIMBERLEY SKELTON This article illuminates the changes in English seventeenth-century architectural practice when members of the gentry educated themselves as architectural professionals and as a result several became noted practitioners. The author analyses the rarely examined notes and library of Sir Roger Pratt to explore how a seventeenth-century gentleman both studied and practised architecture literally as both gentleman and architect. Also she considers Pratt’s notes chronologically, rather than according to their previous thematic reorganisation by R. T. Gunther (1928), and offers a full reconstruction of Pratt’s library beyond Gunther’s catalogue of surviving volumes. Mid-seventeenth-century England experienced a sharp change in architectural practice and education. For the first time, members of the gentry began to design buildings and to educate themselves as professionals in architecture. From the late 1650s, Sir Roger Pratt designed country houses, and several members of the landed and educated classes became prominent architects: Sir Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Hugh May, William Winde, William Samwell, and William Talman. These gentleman architects brought new techniques to the study of architecture since they were more highly trained in analysing text than image. Scholars have yet to consider the seventeenth-century emergence of the gentleman architect in detail; they have focused more on monographic studies of architects, patronage, and building types than on shifts in the architectural profession.1 This article explores how a seventeenth-century gentleman would both study and practise architecture; it considers the rarely examined library and manuscript notes of Sir Roger Pratt.2 I argue that Pratt practised and read as literally patron and architect – using the techniques of a patron to answer the questions of an architect designing for English geographical and social particularities. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 04 April 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: O'Brien, John (2013) 'Montaigne, Sir Ralph Bankes and other English readers of the Essais.', Renaissance studies., 28 (3). pp. 377-391. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12026 Publisher's copyright statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: O'Brien, John (2014). Montaigne, Sir Ralph Bankes and other English readers of the Essais. Journal of the Society for Renaissance Studies 28(3): 377-391, which has been published in nal form at https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12026. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Montaigne, Sir Ralph Bankes and other English Readers of the Essais John O’Brien The study of Montaigne in early-modern England has taken a particular turn in recent years. -

'X'marks the Spot: the History and Historiography of Coleshill House

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of History ‘X’ Marks the Spot: The History and Historiography of Coleshill House, Berkshire by Karen Fielder Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy ‘X’ MARKS THE SPOT: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY OF COLESHILL HOUSE, BERKSHIRE by Karen Fielder Coleshill House was a much admired seventeenth-century country house which the architectural historian John Summerson referred to as ‘a statement of the utmost value to British architecture’. Following a disastrous fire in September 1952 the remains of the house were demolished amidst much controversy shortly before the Coleshill estate including the house were due to pass to the National Trust. The editor of The Connoisseur, L.G.G. Ramsey, published a piece in the magazine in 1953 lamenting the loss of what he described as ‘the most important and significant single house in England’. ‘Now’, he wrote, ‘only X marks the spot where Coleshill once stood’. Visiting the site of the house today on the Trust’s Coleshill estate there remains a palpable sense of the absent building. This thesis engages with the house that continues to exist in the realm of the imagination, and asks how Coleshill is brought to mind not simply through the visual signals that remain on the estate, but also through the mental reckoning resulting from what we know and understand of the house. In particular, this project explores the complexities of how the idea of Coleshill as a canonical work in British architectural histories was created and sustained over time.