TOCC0445DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

SERIE MUSIK DENKEN / MUSIC THINKING 17.1.2013 Jorge López

SERIE MUSIK DENKEN / MUSIC THINKING 17.1.2013 Jorge López (Composer) IMPRESSIONISTIC NOTES ON PRESENTING PETTERSSON’S SIXTH AND ELEVENTH AT THE CONSERVATORY CITY OF VIENNA UNIVERSITY 17. January 2013: About 20 people showed up, including a lady from the Swedish Embassy in Vienna, whose financial support had made my work possible. The conservatory’s Professor Susana Zapke, who had organized the seminar, provided an introduction, while Dr. Peter Kislinger of the Vienna University, who has done some excellent radio programs for the Austrian Radio ORF on composers such as Pettersson, Eliasson, and Aho, kindly served on short notice as moderator. I kept the Pettersson biography short and simple. The arthritis was certainly crippling and real, but that Gudrun had money so that Allan could compose also seems to be real. Just reeling off the same highly emotional AP quotes about this and that is in my opinion, 33 years after Allan’s death, essentially counterproductive. What we have and what we should deal with is HIS MUSIC. He had studied not only in Stockholm with renowned Swedish composers but also in Paris with René Leibowitz, and through Leibowitz thoroughly absorbed the music of the Second Viennese School. And this often comes through—when I hear the beginning of AP’s FIFTH I sense in the four-pitch groups something subliminally reminiscent of Webern’s (weak and cramped) String Quartet Op. 28— here set free by Pettersson into experiential time and space. Ah yes, time and space. There is a concept or model or field or archetype for Scandinavian symphonic writing that I find to be fundamentally different from that of Central European thinking: one grounded not on consciously worked-out contrast and dialectic but rather on the intuitive experience of the symphony as JOURNEY through time and space. -

Transparent200‘6 Annual Report ‘6200 Contents Annual Report‘6 ADDRESS 8

annual report transparent200‘6 annual report ‘6200 Contents annual report‘6 ADDRESS 8 BANK’S PORTRAIT 12 Key Financial Ratios 14 Main achievements in 2006 15 Shareholders, Board of Directors, Management Board 15 RESULTS OF BANK TURANALEM DEVELOPMENT IN 2006 18 Kazakhstan economic and banking sector performance in 2006 20 BTA group development 22 DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY OF BANK TURANALEM 24 CORPORATE BUSINESS 28 RETAIL BUSINESS 32 SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED BUSINESS 38 SUBSIDIARIES 42 Insurance market 44 Pension market 45 Investment market 45 Leasing market 46 Mortgage market 46 STOCK MARKETS 48 Treasury operations in the stock market 50 International Capital Markets 50 Syndicated loans 51 Trade financing 52 annual report BTA GROUP’S MANAGEMENT SYSTEM 54 The structure of BTA group 56 ‘6 Corporate governance 57 Risk management and internal control 57 Human resources management 58 Social responsibility 60 BTA GROUP’S FINANCIAL STANDING REVIEW 64 Net interest income 66 Non-interest income 66 Operational expenditures, taxation, net income 67 Financial performance 67 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 70 Report of independent auditors 72 Consolidated balance sheets 73 Consolidated statement of income 74 Consolidated statements of changes in share capital 75 Consolidated statements of cash flows 78 ADDRESS annual report‘6 annual report DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, CUSTOMERS AND STAFF MEMBERS OF THE BANK! In 2006 Bank «TuranAlem» despite tough competition remained its leading positions and showed impressive growth rates. We tripled net income and more than doubled share- ‘6 holders’ capital and assets. We made one more step to establish the bank as CIS largest financial institute by starting the asset consolidation program. -

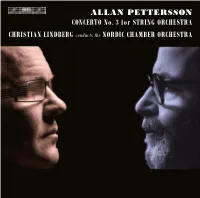

ALLAN PETTERSSON CONCERTO No. 3 for STRING ORCHESTRA CHRISTIAN LINDBERG Conducts the NORDIC CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

ALLAN PETTERSSON CONCERTO No. 3 for STRING ORCHESTRA CHRISTIAN LINDBERG conducts the NORDIC CHAMBER ORCHESTRA BIS-CD-1590 BIS-CD-1590_f-b.indd 1 10-01-14 16.37.22 BIS-CD-1590 Pettersson Q8:booklet 11/01/2010 10:33 Page 3 PETTERSSON, [Gustaf] Allan (1911–80) Concerto No.3 for string orchestra (1956–57) 53'30 1 I. Allegro con moto 16'30 2 II. Mesto 25'10 3 III. Allegro con moto 11'29 Nordic Chamber Orchestra Sundsvall Jonas Lindgård leader Christian Lindberg conductor Publishers: I & III: Swedish Radio II: Gehrmans Musikförlag 3 BIS-CD-1590 Pettersson Q8:booklet 11/01/2010 10:33 Page 4 fter the emergence of a substantial number of serenades and suites for string orchestra in the second half of the nineteenth century (for instance A the well-known works by Antonín Dvořák, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Edvard Grieg), the repertoire was extended once again in the 1940s and 1950s by numerous compositions including Béla Bartók’s Divertimento (1940) and Witold Lutosławski’s Trauermusik (1954–58). The fact that many of these compositions are highly demanding works reveals that this new flowering of interest in ensem - bles of strings alone was not motivated primarily by educational goals. We can also dismiss the notion that a supposed reduction of instrumental forces reflected the economic circumstances of the period – as had been the case with the un ex - pected upsurge in string quartet composition after the First World War. This re - course to the string orchestra should rather be seen in the light of the broader creat ive welcome accorded by modern composers to the music of the early eigh - teenth century – their contributions often being labelled ‘neo-classical’ or ‘neo- baroque’. -

A List of Symphonies the First Seven: 1

A List of Symphonies The First Seven: 1. Anton Webern, Symphonie, Op. 21 2. Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 2 3. Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 4 4. Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. 5 5. Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 8 6. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 2 op. 38b 7. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 1 op. 9b The Others: Stefan Wolpe, Symphony No. 1 Matthijs Vermeulen, Symphony No. 6 (“Les Minutes heureuses”) Allan Pettersson, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 6, Symphony No. 8, Symphony No. 13 Wallingford Riegger, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 3 Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2 Alain Bancquart, Symphonie n° 1, Symphonie n° 5 (“Partage de midi” de Paul Claudel) Hanns Eisler, Kammer-Sinfonie Günter Kochan, Sinfonie Nr.3 (In Memoriam Hanns Eisler), Sinfonie Nr.4 Ross Lee Finney, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Darius Milhaud, Symphony No. 8 (“Rhodanienne”, Op. 362: Avec mystère et violence) Gian Francesco Malipiero, Symphony No. 9 ("dell'ahimé"), Symphony No. 10 ("Atropo"), & Symphony No. 11 ("Della Cornamuse") Roberto Gerhard, Symphony No. 1, No. 2 ("Metamorphoses") & No. 4 (“New York”) E.J. Moeran, Symphony in g minor Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 9 Edison Denisov, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2; Chamber Symphony No. 1 (1982) Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 1 Sir Edward Elgar, Symphony No. 2, Symphony No. 1 Frank Corcoran, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Ernst Krenek, Symphony No. 5 Erwin Schulhoff, Symphony No. 1 Gerd Domhardt, Sinfonie Nr.2 Alvin Etler, Symphony No. 1 Meyer Kupferman, Symphony No. 4 Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. -

Kazakistan - Tataristan İlişkilerine Analitik Bir Bakış

Makale Gönderilme Tarihi / Article Submission Date: 26-02-2020 Makale Kabul Tarihi / Article Acceptance Date: 27-02-2020 Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF VOLGA - URAL AND TURKESTAN STUDIES (IJVUTS), VOLUME 2, ISSUE 3, P. 119 – 149. ULUSLARARASI İDİL - URAL VE TÜRKİSTAN ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ (IJVUTS), CİLT 2, SAYI 3, S. 119 – 149. Kazakistan - Tataristan İlişkilerine Analitik Bir Bakış Hayrettin SAĞDIÇ Özet 1991’de bağımsızlığını ilan eden Kazakistan, ilk dönemlerde “toprak bütünlüğünü güvence altına alma ve ekonomik kalkınma” hedeflerine odaklanarak çok yönlü bir dış politika stratejisi izlemiştir. Ekonomisi gelişen Kazakistan, 2000’li yılların ortalarından itibaren bölgesel güç olma yolunda ilerlemeye başlamış; Avrasya Ekonomik Birliği, Orta Asya Birliği, Türk Konseyi gibi birçok uluslararası inisiyatife öncülük etmiştir. Kazakistan’ın ilgi alanı Orta Asya coğrafyasıyla sınırlı değildir. Kazaklar; ortak dil, din, tarih, kültür bağlarına sahip oldukları İdil-Ural Türklüğüyle de yakın ilişkiler geliştirmeye çalışmaktadır. Kazakistan’da yaşayan 200 binin üzerindeki Tatar nüfusu, bu ilişkilerde bir köprü görevi görmektedir. Kazakistan’ın Tatar nüfusuna yönelik bu ilgisi, Tataristan’la kurduğu yakın ilişkilerin sonucudur. Kazak Hanlığını Altın Ordu Devleti’nin devamı, kendilerini de Altınordu’nun doğal mirasçısı kabul eden Kazaklar, ortak kökenleri dolayısıyla İdil- Ural Türklüğüne karşı sempati beslemektedir. Kazakistan Cumhurbaşkanı Kasımjomart Tokayev, Altın Ordu Devleti’ni Kazakların kültürel kodlarının önemli bir parçası olarak nitelendirmiştir. 2020-2022 yılları Kazakistan’da “Altın Ordu’nun Kuruluşunun 750. Yılı” olarak resmî etkinliklerle kutlanacaktır. Ekonomik- ticari boyutu bir kenara bırakılacak olursa bu bağlar, son yıllarda canlanan Kazakistan-Tataristan ilişkilerini izaha yeter. Ancak kanaatimizce bu yakın ilişkilerin bir nedeni de ülkenin özellikle kuzey bölgelerinde Kazak nüfusunun düşük olmasının oluşturduğu demografik risklere karşı Tatarların bir dayanak noktası olarak görülmesidir. -

New • Nouveaute • Neuheit

NEW • NOUVEAUTE • NEUHEIT 04/11-(6) Gustav Allan Pettersson (1911-1980) Chamber Music Concerto for Violin and String Quartet 3 Pieces for Violin and Piano Sonatas No. 2, 3 + 7 for 2 Violins Yamei Yu, violin Andreas Seidel, violin Chia Chou, piano Leipziger Streichquartett 1 CD Order No.: MDG 307 1528-2 UPC-Code: For G.A. Pettersson’s centenary on 19 Sep 2011 Ruling Passion First-Class Boundless and immense love for music and decades Yamei Yu was born in Tianjin, PR of China and of hard work brought Gustav Allan Pettersson from studied in Peking, Munich, and Berlin. She was Stockholm’s slums to the world’s concert stages. The principal concertmaster of the Komische Oper in Leipzig String Quartet together with the violinist Yamei Berlin from 1996 to 2001 and of the the Bavarian Yu and the pianist Chia Chou presents us chamber State Opera in Munich under Zubin Mehta from 2001 works by this Swedish composer, with a focus on the to 2010. Yamei Yu has performed as soloist with mid-twentieth century. conductors such as Lord Yehudi Menuhin, Kent Nagano, Igor Bolton, Sebastian Weigle, Shao-Jia Lü Self-Made Man and Christoph Poppen. As a youth Pettersson sold Christmas cards to earn In May 2005 she became member of the renowned the money for his first violin. At the age of nineteen Piano Trio Trio Parnasssus . Together with the pianist the self-taught musician passed the entrance Chia Chou and the cellist Michael Gross she has examination at the conservatory in his native recorded several rarely-heard gems. -

ALLAN PETTERSSON Symphony No

ALLAN PETTERSSON Symphony No. 12 The Dead in the Square SWEDISH RADIO CHOIR · ERIC ERICSON CHAMBER CHOIR NORRKÖPING SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA · CHRISTIAN LINDBERG BIS-2450 PETTERSSON, Allan (1911—80) Symphony No. 12, ‘De döda på torget’ (1973—74) (Gehrmans) 55'10 for mixed choir and orchestra. Text: Pablo Neruda (Los muertos de la plaza) 1 Beginning. De döda på torget (The Dead in the Square) 10'53 2 Bar 323. Massakern (The Massacres) 8'23 3 Bar 646. Nitratets män (The Men of the Nitrate) 5'20 4 Bar 840. Döden (Death) 4'44 5 Bar 984. Hur fanorna föddes (How the Flags were Born) 1'22 6 Bar 1023. Jag kallar på dem (I Call on Them) 5'46 7 Bar 1204. Fienderna (The Enemies) 6'51 8 Bar 1414. Här är de (Here They Are) 3'16 9 Bar 1520. Alltid (Always) 8'35 Swedish Radio Choir · Eric Ericson Chamber Choir Hans Vainikainen chorus master Norrköping Symphony Orchestra Jannika Gustafsson leader Christian Lindberg conductor 2 omposer Allan Petterson (1911–80) enjoyed a high level of success in the years around 1970. A major breakthrough had come with his Seventh Sym- Cphony, first performed in 1968. The symphony was recorded, winning two Swedish Grammis awards in 1970. In that same year Allan Pettersson was elected as a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. At the time he was working on his giant Ninth Symphony but shortly after this had been completed he was admitted to hos pital with a kidney disease. His condition was very serious and he remained in hospital for nine months. -

How to Get a Job with a Record Company HIGH JUNE 1978 51.25 ENEL 1111111111.114- 91111F08398

In How to Get a Job with a Record Company HIGH JUNE 1978 51.25 ENEL 1111111111.114- 91111f08398 The Quest for the Ultimate- Two Experts Take Contrary Views Laboratory/Listening Reports: New Speakers from AdventJBLKoss LeakScott - gn 411.11. 06 0 7482008398 hied it not only gives le base greater density, le glue between the eces acts to damp bration. So when you're Common staples can work themselves loose, which is why Pioneer uses aluminum screws >tening to a record, you to mount the base plate to the base. on't hear the turntable. THINKING ON OUR FEET Instead of skinny screw -on plastic legs, oneer uses large shock mounted rubber feet iat not only support the weight of the turntable, Stiff plastic legs merely support most turntables, Pioneer's massive spring -mounted rubber feet also reduce feedback. t absorb vibration and reduce acoustic -edback. So it you like to play your music loud The ordinary lough to rattle the walls, you won't run the risk platter mat is flat. Ours is concave rattling the turntable. w compensate for warped records. FEATURES YOU MIGHT OTHERWISE Smaller, OVERLOOK. conventional platters are more subject to Besides the big things, the PL -518 has other iMIIIIIIIIIIMgimmo.umm. speed variations than our massive ss obvious advantages. PV platter Our platter mat, for example, is concave to )mpensate for warped records. screws to seal the base plate to the base. The platter itself is larger than others in this It's details like these as wellas advanced price range, which means it technology that gives the PL -518an incredibly stays at perfect speed with high signal-to-noise ratio of 73 decibels. -

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS a Discography Of

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers H-P GAGIK HOVUNTS (see OVUNTS) AIRAT ICHMOURATOV (b. 1973) Born in Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia. He studied clarinet at the Kazan Music School, Kazan Music College and the Kazan Conservatory. He was appointed as associate clarinetist of the Tatarstan's Opera and Ballet Theatre, and of the Kazan State Symphony Orchestra. He toured extensively in Europe, then went to Canada where he settled permanently in 1998. He completed his musical education at the University of Montreal where he studied with Andre Moisan. He works as a conductor and Klezmer clarinetist and has composed a sizeable body of music. He has written a number of concertante works including Concerto for Viola and Orchestra No1, Op.7 (2004), Concerto for Viola and String Orchestra with Harpsicord No. 2, Op.41 “in Baroque style” (2015), Concerto for Oboe and Strings with Percussions, Op.6 (2004), Concerto for Cello and String Orchestra with Percussion, Op.18 (2009) and Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op 40 (2014). Concerto Grosso No. 1, Op.28 for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, Piano and String Orchestra with Percussion (2011) Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp (2009) Elvira Misbakhova (viola)/Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + Concerto Grosso No. 1 and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) ARSHAK IKILIKIAN (b. 1948, ARMENIA) Born in Gyumri Armenia. -

Abstracts Abstracts

106 Abstracts Abstracts Michael Kube: »For this, you need distance«. Biography and Work between Self-staging and Reflection Allan Pettersson is one of those composers which give the impression, even on first glance, that biography and œuvre form an inner as well as an outer entity. At the same time, the confessional nature of his work and the pressing, express- ive character of his scores in their almost exclusively sinfonic dimensions stands in contrast to a life showing hardly any dramatic experiences or events. How- ever, not only his works demand a sophisticated analysis, even more so do the few stations of lasting effect in his outer biography as well as his writings and statements often referring to them. This is shown even by a cursory walk through these outer conditions, constellations and manifestations – summar- ized only briefly here – which generated the majority of those topoi deter- mining the critical Pettersson reception. Übersetzung: Claudia Brusdeylins * Alexander Keuk: Adherence and Release. The constitution of a musical sig- nature in the music of Allan Pettersson Allan Pettersson’s music eludes any categorization within the music of the 20th century and cannot be assigned to a certain direction of style. The purpose of this text is to specify the reasons and conditions of particular characteristics in Pettersson’s symphonic works. The survey of evidently style-forming early compositions and the first three completed symphonies is related with Pet- tersson’s biography and the composer’s statements about music and style. After early attempts there can be named three compositions which form a basis and a repertory concerning the creation of the symphonies: the Barefoot Songs, quoted far often by Pettersson himself and forming a soulful »coming home«, secondly the 1st Violin Concerto being Pettersson’s first musical appearance in public and which is style-forming in terms of harmony and motives. -

ALLAN PETTERSSON EIGHT BAREFOOT SONGS CONCERTOS Nos 1 & 2 for STRING ORCHESTRA

ALLAN PETTERSSON EIGHT BAREFOOT SONGS CONCERTOS Nos 1 & 2 for STRING ORCHESTRA CHRISTIAN LINDBERG conducts the NORDIC CHAMBER ORCHESTRA BIS-CD-1690 Anders Larsson baritone BIS-CD-1690_f-b.indd 1 09-01-19 13.21.02 BIS-CD-1690 Pettersson:booklet 19/1/09 12:38 Page 2 PETTERSSON, [Gustaf] Allan (1911–80) Eight Barefoot Songs (1943–45) 23'48 orchestrated by Antal Doráti. Texts: Allan Pettersson 1 1. Herren går på ängen 2'20 2 2. Klokar och knythänder 3'12 3 3. Blomma, säj 1'42 4 4. Jungfrun och ljugarpust 5'01 5 5. Mens flugorna surra 2'59 6 6. Du lögnar 1'46 7 7. Min längtan 2'33 8 8. En spelekarls himlafärd 3'47 Concerto No.1 for string orchestra (1949–50) 20'41 9 I. Allegro 8'55 10 II. Andante 4'22 11 III. Largamente – Allegro 7'16 Concerto No. 2 for string orchestra (1956) 26'46 12 I. Allegro 7'01 13 II. Dolce e molto tranquillo 5'49 14 III. Allegro 13'39 TT: 72'21 Anders Larsson baritone Nordic Chamber Orchestra Sundsvall Jonas Lindgård leader Christian Lindberg conductor All works published by Nordiska Musikförlaget BIS-CD-1690 Pettersson:booklet 19/1/09 12:38 Page 3 he 24 Barefoot Songs (Barfotasånger) for voice and piano were composed in 1943–45 and must be regarded as a pivotal work in Allan Pettersson’s life and Twork. The texts are by the composer himself, and in the words as in the music he reflects not only the difficulties of his childhood and youth – tainted by poverty and social ex clusion –and his longing for a ‘more beautiful’ life, but also his mother’s strict reli gious attitudes and his father’s alcoholism.