ALLAN PETTERSSON EIGHT BAREFOOT SONGS CONCERTOS Nos 1 & 2 for STRING ORCHESTRA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SERIE MUSIK DENKEN / MUSIC THINKING 17.1.2013 Jorge López

SERIE MUSIK DENKEN / MUSIC THINKING 17.1.2013 Jorge López (Composer) IMPRESSIONISTIC NOTES ON PRESENTING PETTERSSON’S SIXTH AND ELEVENTH AT THE CONSERVATORY CITY OF VIENNA UNIVERSITY 17. January 2013: About 20 people showed up, including a lady from the Swedish Embassy in Vienna, whose financial support had made my work possible. The conservatory’s Professor Susana Zapke, who had organized the seminar, provided an introduction, while Dr. Peter Kislinger of the Vienna University, who has done some excellent radio programs for the Austrian Radio ORF on composers such as Pettersson, Eliasson, and Aho, kindly served on short notice as moderator. I kept the Pettersson biography short and simple. The arthritis was certainly crippling and real, but that Gudrun had money so that Allan could compose also seems to be real. Just reeling off the same highly emotional AP quotes about this and that is in my opinion, 33 years after Allan’s death, essentially counterproductive. What we have and what we should deal with is HIS MUSIC. He had studied not only in Stockholm with renowned Swedish composers but also in Paris with René Leibowitz, and through Leibowitz thoroughly absorbed the music of the Second Viennese School. And this often comes through—when I hear the beginning of AP’s FIFTH I sense in the four-pitch groups something subliminally reminiscent of Webern’s (weak and cramped) String Quartet Op. 28— here set free by Pettersson into experiential time and space. Ah yes, time and space. There is a concept or model or field or archetype for Scandinavian symphonic writing that I find to be fundamentally different from that of Central European thinking: one grounded not on consciously worked-out contrast and dialectic but rather on the intuitive experience of the symphony as JOURNEY through time and space. -

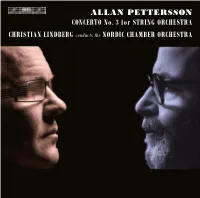

ALLAN PETTERSSON CONCERTO No. 3 for STRING ORCHESTRA CHRISTIAN LINDBERG Conducts the NORDIC CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

ALLAN PETTERSSON CONCERTO No. 3 for STRING ORCHESTRA CHRISTIAN LINDBERG conducts the NORDIC CHAMBER ORCHESTRA BIS-CD-1590 BIS-CD-1590_f-b.indd 1 10-01-14 16.37.22 BIS-CD-1590 Pettersson Q8:booklet 11/01/2010 10:33 Page 3 PETTERSSON, [Gustaf] Allan (1911–80) Concerto No.3 for string orchestra (1956–57) 53'30 1 I. Allegro con moto 16'30 2 II. Mesto 25'10 3 III. Allegro con moto 11'29 Nordic Chamber Orchestra Sundsvall Jonas Lindgård leader Christian Lindberg conductor Publishers: I & III: Swedish Radio II: Gehrmans Musikförlag 3 BIS-CD-1590 Pettersson Q8:booklet 11/01/2010 10:33 Page 4 fter the emergence of a substantial number of serenades and suites for string orchestra in the second half of the nineteenth century (for instance A the well-known works by Antonín Dvořák, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Edvard Grieg), the repertoire was extended once again in the 1940s and 1950s by numerous compositions including Béla Bartók’s Divertimento (1940) and Witold Lutosławski’s Trauermusik (1954–58). The fact that many of these compositions are highly demanding works reveals that this new flowering of interest in ensem - bles of strings alone was not motivated primarily by educational goals. We can also dismiss the notion that a supposed reduction of instrumental forces reflected the economic circumstances of the period – as had been the case with the un ex - pected upsurge in string quartet composition after the First World War. This re - course to the string orchestra should rather be seen in the light of the broader creat ive welcome accorded by modern composers to the music of the early eigh - teenth century – their contributions often being labelled ‘neo-classical’ or ‘neo- baroque’. -

A List of Symphonies the First Seven: 1

A List of Symphonies The First Seven: 1. Anton Webern, Symphonie, Op. 21 2. Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 2 3. Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 4 4. Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. 5 5. Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 8 6. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 2 op. 38b 7. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 1 op. 9b The Others: Stefan Wolpe, Symphony No. 1 Matthijs Vermeulen, Symphony No. 6 (“Les Minutes heureuses”) Allan Pettersson, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 6, Symphony No. 8, Symphony No. 13 Wallingford Riegger, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 3 Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2 Alain Bancquart, Symphonie n° 1, Symphonie n° 5 (“Partage de midi” de Paul Claudel) Hanns Eisler, Kammer-Sinfonie Günter Kochan, Sinfonie Nr.3 (In Memoriam Hanns Eisler), Sinfonie Nr.4 Ross Lee Finney, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Darius Milhaud, Symphony No. 8 (“Rhodanienne”, Op. 362: Avec mystère et violence) Gian Francesco Malipiero, Symphony No. 9 ("dell'ahimé"), Symphony No. 10 ("Atropo"), & Symphony No. 11 ("Della Cornamuse") Roberto Gerhard, Symphony No. 1, No. 2 ("Metamorphoses") & No. 4 (“New York”) E.J. Moeran, Symphony in g minor Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 9 Edison Denisov, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2; Chamber Symphony No. 1 (1982) Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 1 Sir Edward Elgar, Symphony No. 2, Symphony No. 1 Frank Corcoran, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Ernst Krenek, Symphony No. 5 Erwin Schulhoff, Symphony No. 1 Gerd Domhardt, Sinfonie Nr.2 Alvin Etler, Symphony No. 1 Meyer Kupferman, Symphony No. 4 Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. -

New • Nouveaute • Neuheit

NEW • NOUVEAUTE • NEUHEIT 04/11-(6) Gustav Allan Pettersson (1911-1980) Chamber Music Concerto for Violin and String Quartet 3 Pieces for Violin and Piano Sonatas No. 2, 3 + 7 for 2 Violins Yamei Yu, violin Andreas Seidel, violin Chia Chou, piano Leipziger Streichquartett 1 CD Order No.: MDG 307 1528-2 UPC-Code: For G.A. Pettersson’s centenary on 19 Sep 2011 Ruling Passion First-Class Boundless and immense love for music and decades Yamei Yu was born in Tianjin, PR of China and of hard work brought Gustav Allan Pettersson from studied in Peking, Munich, and Berlin. She was Stockholm’s slums to the world’s concert stages. The principal concertmaster of the Komische Oper in Leipzig String Quartet together with the violinist Yamei Berlin from 1996 to 2001 and of the the Bavarian Yu and the pianist Chia Chou presents us chamber State Opera in Munich under Zubin Mehta from 2001 works by this Swedish composer, with a focus on the to 2010. Yamei Yu has performed as soloist with mid-twentieth century. conductors such as Lord Yehudi Menuhin, Kent Nagano, Igor Bolton, Sebastian Weigle, Shao-Jia Lü Self-Made Man and Christoph Poppen. As a youth Pettersson sold Christmas cards to earn In May 2005 she became member of the renowned the money for his first violin. At the age of nineteen Piano Trio Trio Parnasssus . Together with the pianist the self-taught musician passed the entrance Chia Chou and the cellist Michael Gross she has examination at the conservatory in his native recorded several rarely-heard gems. -

ALLAN PETTERSSON Symphony No

ALLAN PETTERSSON Symphony No. 12 The Dead in the Square SWEDISH RADIO CHOIR · ERIC ERICSON CHAMBER CHOIR NORRKÖPING SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA · CHRISTIAN LINDBERG BIS-2450 PETTERSSON, Allan (1911—80) Symphony No. 12, ‘De döda på torget’ (1973—74) (Gehrmans) 55'10 for mixed choir and orchestra. Text: Pablo Neruda (Los muertos de la plaza) 1 Beginning. De döda på torget (The Dead in the Square) 10'53 2 Bar 323. Massakern (The Massacres) 8'23 3 Bar 646. Nitratets män (The Men of the Nitrate) 5'20 4 Bar 840. Döden (Death) 4'44 5 Bar 984. Hur fanorna föddes (How the Flags were Born) 1'22 6 Bar 1023. Jag kallar på dem (I Call on Them) 5'46 7 Bar 1204. Fienderna (The Enemies) 6'51 8 Bar 1414. Här är de (Here They Are) 3'16 9 Bar 1520. Alltid (Always) 8'35 Swedish Radio Choir · Eric Ericson Chamber Choir Hans Vainikainen chorus master Norrköping Symphony Orchestra Jannika Gustafsson leader Christian Lindberg conductor 2 omposer Allan Petterson (1911–80) enjoyed a high level of success in the years around 1970. A major breakthrough had come with his Seventh Sym- Cphony, first performed in 1968. The symphony was recorded, winning two Swedish Grammis awards in 1970. In that same year Allan Pettersson was elected as a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. At the time he was working on his giant Ninth Symphony but shortly after this had been completed he was admitted to hos pital with a kidney disease. His condition was very serious and he remained in hospital for nine months. -

Abstracts Abstracts

106 Abstracts Abstracts Michael Kube: »For this, you need distance«. Biography and Work between Self-staging and Reflection Allan Pettersson is one of those composers which give the impression, even on first glance, that biography and œuvre form an inner as well as an outer entity. At the same time, the confessional nature of his work and the pressing, express- ive character of his scores in their almost exclusively sinfonic dimensions stands in contrast to a life showing hardly any dramatic experiences or events. How- ever, not only his works demand a sophisticated analysis, even more so do the few stations of lasting effect in his outer biography as well as his writings and statements often referring to them. This is shown even by a cursory walk through these outer conditions, constellations and manifestations – summar- ized only briefly here – which generated the majority of those topoi deter- mining the critical Pettersson reception. Übersetzung: Claudia Brusdeylins * Alexander Keuk: Adherence and Release. The constitution of a musical sig- nature in the music of Allan Pettersson Allan Pettersson’s music eludes any categorization within the music of the 20th century and cannot be assigned to a certain direction of style. The purpose of this text is to specify the reasons and conditions of particular characteristics in Pettersson’s symphonic works. The survey of evidently style-forming early compositions and the first three completed symphonies is related with Pet- tersson’s biography and the composer’s statements about music and style. After early attempts there can be named three compositions which form a basis and a repertory concerning the creation of the symphonies: the Barefoot Songs, quoted far often by Pettersson himself and forming a soulful »coming home«, secondly the 1st Violin Concerto being Pettersson’s first musical appearance in public and which is style-forming in terms of harmony and motives. -

Allan Pettersson Performances

Allan Pettersson Performances Jürgen Lange March 29, 2016 Performances [1] Torleif Lännerholm, Tore Westlund, and Tore Rönnebäck. Pettersson Fuga in E for Oboe, Clarinet and Bassoon. Stockholm, Swedish Radio, 1950-09-14:Premiere, September 1950. [2] Musical Society Fylkingen, Lars Frydén, Soldan Ridderstad, Karl-Olof Nihlman, Axel Jonsson, and Bengt Ericson. Pettersson Concerto for Violin and String Quartet. Stockholm, Fylkingen, 1951-03-10:Premiere, March 1951. [3] Carl Garaguly, Bronislav Gimpel, and Kungliga Filharmonikerna. Pet- tersson Konsert för stråkar nr 1. Stockholm, Konserthuset, Stora salen, 1952-11-19 20:00, November 1952. [4] Carl Garaguly, Bronislav Gimpel, and Kungliga Filharmonikerna. Pet- tersson Konsert för stråkar nr 1. Stockholm, Konserthuset, Stora salen, 1952-11-20 20:00, November 1952. [5] Monique Janne and Fran Onfroy. Pettersson Seven Sonatas for Two Violins No. 3 and 7. Paris, Salle de l’Ecole Normale de musique, 1952-12- 16:Premiere, December 1952. [6] Tor Mann and Sveriges Radios Symfoniorkester. Pettersson Concerto No. 1 for String Orchestra. Stockholm, Swedish Radio, 1952-04-06:Premiere, April 1952. [7] Hermann Scherchen and Das Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester. Con- certo No. 1 for String Orchestra. Köln, Funkhaus, 1953-05-26 19:00, May 1953. Neues Musikfest, Orchesterkonzert. [8] Matla Temko and Andor Sagi. Pettersson Seven Sonatas for Two Violins No. 1. Stockholm, Fylkingen, 1953-03-28:Premiere, March 1953. [9] Tor Mann and Sveriges Radios Symfoniorkester. Pettersson Symphony No. 2. Stockholm, Musikaliska Akademien, 1954-05-09:Premiere, May 1954. 1 [10] Sixten Ehrling, Tore Wiberg, and Kungliga Filharmonikerna. Pettersson Symfoni nr 2. Stockholm, Konserthuset, Stora salen, 1955-04-29 20:00, April 1955. -

Einojuhani Rautavaara in Memoriam Christian Lindberg & Allan Pettersson

NORDIC HIGHLIGHTS 4/2016 NEWSLETTER FROM GEHRMANS MUSIKFÖRLAG & FENNICA GEHRMAN Einojuhani Rautavaara in memoriam Christian Lindberg & Allan Pettersson NEWS Rautavaara’s Gift of Magi Klami additions to the catalogue Martinsson and Schnelzer on stage Fennica Gehrman has awarded Einojuhani Rautavaara’s chamber opera Th e Gift agreed with the Uuno Rolf Martinsson has Klami Society to publish of the Magi (Tietäjien lahja) is staged at the Si- been awarded the Bäcker Mats Photo: belius Academy. Th e performances in November several works by Uuno Christ Johnson Prize and December are coupled with Humperdinck’s Klami (1900-61). Th ese for his song cycle Or- opera Hansel and Gretel. Markus Lehtinen and include orchestral works chestral Songs on Poems Andres Kaljuste will conduct the students of the – Opernredoute, Aurore by Emily Dickinson Academy. Rautavaara composed this Christmas boréale and the Piano (2009) . According fable in 1994 and it is based on the short story by Concerto “Une nuit à to the Royal Academy O. Henry. It has earlier been performed on TV Montmartre”, among oth- of Music, “with his masterly musical language he in Finland and on stage at the Canberra Music ers – and chamber music. creates a mutual expression of great sonorous lu- Festival, Australia in 2010. Klami is known as a brilliant orchestral compos- minosity”. Th e work was commissioned by the er who fused Finnish modernism with French Malmö Symphony Orchestra and has been per- infl uences. His Kalevala Suite and Sea Pictures Pettersson’s symphony formed numerous times, with great success, by are examples of classics that remain in the soprano Lisa Larsson. -

The Cambridge Companion To: the ORCHESTRA

The Cambridge Companion to the Orchestra This guide to the orchestra and orchestral life is unique in the breadth of its coverage. It combines orchestral history and orchestral repertory with a practical bias offering critical thought about the past, present and future of the orchestra as a sociological and as an artistic phenomenon. This approach reflects many of the current global discussions about the orchestra’s continued role in a changing society. Other topics discussed include the art of orchestration, score-reading, conductors and conducting, international orchestras, and recording, as well as consideration of what it means to be an orchestral musician, an educator, or an informed listener. Written by experts in the field, the book will be of academic and practical interest to a wide-ranging readership of music historians and professional or amateur musicians as well as an invaluable resource for all those contemplating a career in the performing arts. Colin Lawson is a Pro Vice-Chancellor of Thames Valley University, having previously been Professor of Music at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He has an international profile as a solo clarinettist and plays with The Hanover Band, The English Concert and The King’s Consort. His publications for Cambridge University Press include The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet (1995), Mozart: Clarinet Concerto (1996), Brahms: Clarinet Quintet (1998), The Historical Performance of Music (with Robin Stowell) (1999) and The Early Clarinet (2000). Cambridge Companions to Music Composers -

Allan Pettersson Symphony No. 9 Norrköping

Bonus DVD: an enlightening documentary, made available for the first time to a wider international ALLAN PETTERSSON audience through the initiative and generous sponsorship of Christian Lindberg SYMPHONY NO. 9 Människans röst (Vox Humana – The Voice of Man) Allan Pettersson, composer A documentary 1973–78 by Peter Berggren, Tommy Höglind and Gunnar Källström Produced by Peter Berggren and Jonny Mair for Sveriges Television AB (SVT) Digital film restoration & colour grading: Gunnar Källström and David Lindberg Picture format: NTSC – 16:9 & 4:3 pillar box Sound format: Dolby Digital – Stereo Region code: 0 (Worldwide) Languages: Swedish, with English subtitles • Total time: 81’40 DVD Authoring: David Lindberg, DSL film and music productions NORRKÖPING SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA · CHRISTIAN LINDBERG BIS-2038 BIS-2038_f-b.indd 1 2013-09-13 11.18 PETTERSSON, Allan (1911–80) Symphony No. 9 (1970) (Gehrmans) 69'40 1 Beginning 7'38 2 3 bars after Fig. 27 8'58 3 3 bars before Fig. 58 7'56 4 2 bars before Fig. 88 6'45 5 3 bars after Fig. 111 8'13 6 Fig. 139 4'52 7 5 bars after Fig. 153 12'43 8 4 bars after Fig. 189 5'33 9 Fig. 203 6'58 Norrköping Symphony Orchestra Henrik Jon Petersen leader Christian Lindberg conductor 2 very composer who wrote symphonies for performance by the classical symphony orchestra in the second half of the 20th century made a conscious Echoice. Many composers who came to prominence at this time chose to ignore the symphonic genre altogether, not least those whose music tended towards a radical approach. -

Peter Ruzicka Komponist, Dirigent Und Intendant

PERSÖNLICHKEITEN DER SALZBURGER MUSIKGESCHICHTE EIN PROJEKT DES ARBEITSSCHWERPUNKTES SALZBURGER MUSIKGESCHICHTE AN DER ABTEILUNG FÜR MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT DER UNIVERSITÄT MOZARTEUM PETER RUZICKA KOMPONIST, DIRIGENT UND INTENDANT * 3. JULI 1948 IN DÜSSELDORF „Gleichwohl – sich für eine Idee zu begeistern ist das eine, sie in die Tat umzusetzen etwas grundsätzlich anderes. Ich wusste es von Anfang an und begreife es heute mehr denn je, dass an keinem anderen Ort der Welt, an keinem Opernhaus, bei keinem Festival, dieses in der Theatergeschichte beispiellose Projekt hätte gelingen können. Nur in Salzburg, nur bei den Salzburger Festspielen war eine solche Unternehmung überhaupt denkbar.“ (Ruzicka 2006, S. 10) Der ehemalige Intendant der Salzburger Festspiele, unter dessen Ägide im Mozartjahr 2006 unter dem programmatischen Titel Mozart22 die szenische Aufführung sämtlicher Opern des Genius loci den Spielplan dominierte, begann seine musikalische Ausbildung 1963 am Konservatorium in Hamburg, wo er bei Peter Hartmann Klavier, bei Egbert Gutsch Oboe und bei Walter Steffens Komposition studierte. Einem fächerübergreifenden Ausbildungsfokus gemäß absolvierte er zudem in München, Hamburg und Berlin Studien in Rechtswissenschaft, Betriebswirtschaft sowie Theater- und Musikwissenschaft. Jener interdisziplinäre Ansatz spiegelt sich in seiner Dissertationsschrift über das „ewige Urheberpersönlichkeitsrecht“ wider, mit der er 1977 an der Freien Universität Berlin promovierte. Als für seinen Weg als Komponist besonders prägend gestaltete sich Ruzickas Studium -

The Saxophone Sonata in Twentieth Century America: Chronology and Development of Select Repertoire

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE SAXOPHONE SONATA IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICA: CHRONOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT OF SELECT REPERTOIRE Robert Edward Beeson, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2011 Dissertation directed by: Professor Michael Votta School of Music The first documented American saxophone sonata was composed in1928. From then until 2000, the genre experienced remarkable growth and development that mirrored many of the significant trends of century music. This dissertation traces the development of the sonata through a series of three recitals divided chronologically: 1928-1960 encompassing the sonata’s beginnings, 1960-1980 documenting the growth of the genre, and 1980-2000 covering the continued growth and diversification of the sonata in America. The works performed were selected from the one hundred and sixty six American saxophone sonatas documented in Jean-Marie Londeix’s A Comprehensive Guide To The Saxophone Repertoire:1844-2003. Program notes are furnished for each recital to summarize the musical content of each work, provide a biographical sketch of each composer and convey why it is a significant work in the repertoire. THE SAXOPHONE SONATA IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICA: CHRONOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT OF SELECT REPERTOIRE By Robert Edward Beeson Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Michael Votta, Chair Professor Paul C. Gekker Professor Chris Vadala