Pylon Pylon Box Though Initially Together for a Short While—Only Four

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Shines at Shell

May 24, 2014 Star Shines at Shell PHOTO BY YOSHI JAMES Homage to cult band’s “Third” kicks off Levitt series By Bob Mehr The Levitt Shell’s 2014 summer season opened Friday night, with a teeming crowd of roughly 4,000 who camped out under clear skies to hear the music of Memphis’ greatest cult band Big Star, in a show dedicated to its dark masterpiece, Third. Performed by an all-star troupe of local and national musicians, it was yet another reminder of how the group, critically acclaimed but commercially doomed during their initial run in the early 1970s, has developed into one of the unlikeliest success stories in rock and roll. The Third album — alternately known as Sister Lovers — was originally recorded at Midtown’s Ardent Studios in the mid-’70s, but vexed the music industry at the time, and was given a belated, minor indie-label release at the end of the decade. However, the music and myth of Third would grow exponentially in the decades to come. When it was finally issued on CD in the early ’90s, the record was hailed by Rolling Stone as an “untidy masterpiece ... beautiful and disturbing, pristine and unkempt — and vehemently original.” 1 North Carolina musician Chris Stamey had long been enamored of the record and the idea of recreating the Third album (along with full string arrangements) live on stage. He was close to realizing a version of the show with a reunited, latter- day Big Star lineup, when the band’s camp suffered a series of losses: first, with the passing of Third producer Jim Dickinson in 2009, and then the PHOTO BY YALONDA M. -

Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl: a Memoir Free

FREE HUNGER MAKES ME A MODERN GIRL: A MEMOIR PDF Carrie Brownstein | 256 pages | 05 Nov 2015 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780349007922 | English | London, United Kingdom Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl by Carrie Brownstein: | : Books Look Inside. Oct 27, Minutes Buy. Before Carrie Brownstein became a music icon, she was a young girl growing up in the Pacific Northwest just as it was becoming the setting for one the most important movements in rock history. Seeking a sense of home and identity, she would discover both while moving from spectator to creator in experiencing the power and mystery of a live performance. With Sleater-Kinney, Brownstein and her bandmates rose to prominence in the burgeoning underground feminist punk-rock movement that would define music and pop culture in the s. With deft, lucid prose Brownstein proves herself as formidable on the page as on the stage. That quality has become obvious over the course of eight albums with bandmates Corin Tucker and Janet Weiss… and now in her refreshingly forthright new memoir, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl. Instead, she candidly recounts the panic attacks and stress-induced shingles she experienced on tour. More important, it shows how compelling she is when she opens up. She carries a lot of humor and gentle self-deprecation throughout the work. For Carrie Brownstein, who grew up in the Riot Grrrl movement in the Pacific Northwest, they did: She started out playing in countless punk bands until settling on one with her BFF and romantic partner, Corin Tucker, which they eventually turned into the best rock band of all time, Sleater-Kinney. -

David Menconi

David Menconi “But tonight, we’re experiencing something much more demented. Something much more American. And something much more crazy. I put it to you, Bob: Goddammit, what’s goin’ on?” —Dexter Romweber, “2 Headed Cow” (1986) (Or as William Carlos Williams put it 63 years earlier: “The Pure Products of America/Go crazy.”) To the larger world outside the Southeastern college towns of Chapel Hill and Athens, Flat Duo Jets’ biggest brush up against the mainstream came with the self-titled first album comprising the heart of this collection. That was 1990’s “Flat Duo Jets,” a gonzo blast of interstellar rockabilly firepower that turned Jack White, X’s Exene Cervenka and oth- er latterday American underground-rock stars into fans and acolytes. In its wake, the Jets toured America with The Cramps and played “Late Night with David Letterman,” astounding audiences with rock ’n’ roll as pure and uncut as anybody was making in the days B.N. (Before Nirvana). But that kind of passionate devotion was nothing new for the Jets. For years, they’d been turning heads and blowing minds in their Chapel Hill home- town as a veritable rite of passage for music-scene denizens of a certain age. Just about everyone in town from that era has a story about happening across the Jets in their mid-’80s salad days, often performing in some terri- bly unlikely place – record store, coffeeshop, hallway, even the middle of the street – channeling some far-off mojo that seemed to open portals to the past and future at the same time. -

Words and Guitar

# 2021/24 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2021/24/words-and-guitar Ein Rückblick auf die Diskographie von Sleater-Kinney Words and Guitar Von Dierk Saathoff Vojin Saša Vukadinović Zehn Alben haben Sleater-Kinney in den 27 Jahren seit ihrer Gründung aufgenommen, von denen das zehnte, »Path of Wellness«, kürzlich erschienen ist. Ein Rückblick auf die Diskographie der wohl besten Band der Welt. »Sleater-Kinney« (LP: Villa Villakula, CD: Chainsaw Records, 1995) 1995 spielten die beiden Gitarristinnen Corin Tucker und Carrie Brownstein erst seit einem Jahr unter dem Namen Sleater-Kinney, waren nach Misty Farrell und Stephen O’Neil (The Cannanes) aber bereits bei der dritten Besetzung am Schlagzeug angelangt, der schottisch-australischen Indie-Musikerin Lora MacFarlane. Nach einer frechen Single und Compilation-Tracks auf Tinuviel Sampsons feministischem Label Villa Villakula erschien dort das Vinyl vom Debütalbum, die CD-Version aber auf Donna Dreschs Queercore-Label Chainsaw. Selten klang Angst durchdringender als auf diesem derben wie dunklen Erstlingswerk, das mit zehn Liedern in weniger als 23 Minuten aufwartet. Corin Tucker kreischt sich die Seele aus dem Leib und Carrie Brownsteins Schreien auf »The Last Song« stellt mit Leichtigkeit ganze Karrieren mediokrer männlicher Hardcore-Bands in den Schatten. Mit Sicherheit nicht nur das unterschätzteste Album der Bandgeschichte, sondern des Punk in den neunziger Jahren überhaupt. »Call the Doctor« (Chainsaw Records, 1996) Album Nummer zwei zeigte eine enorme musikalische Weiterentwicklung. »Call the Doctor« ist das streckenweise intelligenteste Album von Sleater-Kinney, das sich einerseits vor der avancierten Musikszene im Nordwesten der USA verneigte, in der die Band entstanden war (Olympia, Washington), zugleich aber äußerst eigenständig vorwärtspreschte und bei allem Zorn auf die Ausprägungen misogyner Kultur Anflüge von Zärtlichkeit nicht scheute: Selten wurde Unsicherheit so ehrlich vorgetragen wie auf »Heart Attack«. -

The History of Rock Music - the 2000S

The History of Rock Music - The 2000s The History of Rock Music: The 2000s History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2006 Piero Scaruffi) Bards and Dreamers (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Bards of the old world order TM, ®, Copyright © 2008 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Traditionally, the purposefulness and relevance of a singer-songwriter were defined by something unique in their lyrical acumen, vocal skills and/or guitar or piano accompaniment. In the 1990s this paradigm was tested by the trend towards larger orchestrastion and towards electronic orchestration. In the 2000s it became harder and harder to give purpose and meaning to a body of work mostly relying on the message. Many singer-songwriters of the 2000s belonged to "Generation X" but sang and wrote for members of "Generation Y". Since "Generation Y" was inherently different from all the generations that had preceeded it, it was no surprise that the audience for these singer-songwriters declined. Since the members of "Generation X" were generally desperate to talk about themselves, it was not surprising that the number of such singer- songwriters increased. The net result was an odd disconnect between the musician and her or his target audience. The singer-songwriters of the 2000s generally sounded more "adult" because... they were. -

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33 ________________________________________________________________________ 0:00:00 Davis: Today is June 15th, 2017. My name is John Davis. I’m the performing arts metadata archivist at the University of Maryland, speaking to Allison Wolfe. Wolfe: Are you sure it’s the 15th? Davis: Isn’t it? Yes, confirmed. Wolfe: What!? Davis: June 15th… Wolfe: OK. Davis: 2017. Wolfe: Here I am… Davis: Your plans for the rest of the day might have changed. Wolfe: [laugh] Davis: I’m doing research on fanzines, particularly D.C. fanzines. When I think of you and your connection to fanzines, I think of Girl Germs, which as far as I understand, you worked on before you moved to D.C. Is that correct? Wolfe: Yeah. I think the way I started doing fanzines was when I was living in Oregon—in Eugene, Oregon—that’s where I went to undergrad, at least for the first two years. So I went off there like 1989-’90. And I was there also the year ’90-’91. Something like that. For two years. And I met Molly Neuman in the dorms. She was my neighbor. And we later formed the band Bratmobile. But before we really had a band going, we actually started doing a fanzine. And even though I think we named the band Bratmobile as one of our earliest things, it just was a band in theory for a long time first. But we wanted to start being expressive about our opinions and having more of a voice for girls in music, or women in music, for ourselves, but also just for things that we were into. -

ELLIE GOULDING Corin Tucker Band

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM SPOTLIGHT Chris Crisman John Clark CORIN TUCKER BAND The indie rocker chooses musical Seth Lorinczi, Sara Lund, democracy for her new album Corin Tucker, Mike Clark AFTER WRITING ALL THE SONGS Despite the group effort, Kill My working parent, she’s searching for balance on her 2010 solo debut, 1,000 Years, Blues is still defined by Tucker’s voice and between job and family. “That perspective Corin Tucker took a more collaborative her perspective. Backed by volatile riffs comes through on certain songs,” she approach on her latest. Kill My Blues and hooky melodies, she sounds more explains. “‘Constance’ is definitely a song was very much a team effort, as Tucker assured than on her previous release. about being a parent and watching your and her backing musicians jammed out “Making a record after Sleater-Kinney was children grow up and move on. The whole the tunes in their rehearsal space. “We hard,” she says. “It was a real emotional record is really about moving on, and how needed to open more doors for the band challenge.” Having locked in a sense of good that is, and how hard that is.” to evolve,” Tucker says. “That meant writing confidence, Tucker drew inspiration from Not all the tunes are autobiographical. all the songs together and not having it be recent social and political developments with Tucker’s coy about which ones are about just my solo project.” the women’s movement, and from stories her, but whatever their origin the singer Tucker, 39, spent a dozen years writing from her own life and those around her. -

Ocándose Contra Una Pared Entrevista a Martín Karadagián

I c/ lUT» IMPfcCIL SE ACl /ARRIBA/ <3tS» j • "Recital contra la discriminación juvenil" /ATORA/ así se tituló una reunión musical realizada SOALB , « as/ en el Club Arrieta. Una hermosa puñalada y en el vientre de un jóven pedía rabiosamen te tolerancia. "Hay algo aquí que va mal. diría Kortatu. • Material caliente, así se puede definir al video de jóvenes rodado por CEMA. Testi monios de Arte en la Lona, rebeldía sub terránea de Villa Biarriz, la llevada de Este ban y otras cosas. Lo destacable de esta pro ducción -más allá del debut de un jóven director- es la banda sonora original perte neciente a Andy Adler y los Inadaptados de Siempre. • RenzoGurldlToflón, qu®en #u momento nos alcanzara una copla da #u «Impla "la casa cerrada" y no# olvidáramos da acuaar • Noticias de la era pre-glacial: Aquellos recibo, entra en «iludió para grabar IU pri* individuos que deseen mantener un contac mer L.D. solista. Entre loa 'rock liara' qua to con lo que fue la Revista G.A.S. que nos • Seguimos en la radio y hablando de la piensa invitar para o#U» proyecto #e ancuan- escriban, por favor, a Casilla de Correo 6452. poca gente que defiende los intereses del tra Gustavo Parodi. OPor qué no al gordo así no nos sentimos ni tan solos ni tan oxida rock nacional; les comunicamos que Aldo Frade y a Humberto de Vargas? Silva se recuperó del extraño virus que lo dos. mantuvo alejado del chupete y que próxi mamente inicia una nueva experiencia ra • Precisamente de adeenes hablando, su dial en CX 26 (L. -

Art-Rock Legends Pylon to Release Pylon Box

ART-ROCK LEGENDS PYLON TO RELEASE PYLON BOX NOVEMBER 6, 2020, VIA NEW WEST RECORDS COMPREHENSIVE 4xLP BOX SET REMASTERED FROM THE ORIGINAL TAPES FEATURES EIGHTEEN UNRELEASED RECORDINGS INCLUDES 200-PAGE HARDBOUND BOOK WITH WRITINGS BY MEMBERS OF R.E.M., GANG OF FOUR, THE B-52’s, SONIC YOUTH, SLEATER-KINNEY, MISSION OF BURMA, DEERHUNTER, STEVE ALBINI, ANTHONY DECURTIS, AND MORE STANDALONE REISSUES OF STUDIO LPS GYRATE (1980) AND CHOMP (1983) TO BE RELEASED ON VINYL FOR THE FIRST TIME IN NEARLY 35 YEARS; AVAILABLE ACROSS DIGITAL PLATFORMS TODAY PYLON COLLECTION EXHIBIT TO OPEN SEPTEMBER 18 AT THE HARGRETT LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA SPECIAL COLLECTIONS BUILDING JITTERY JOE’S COFFEE ROASTING COMPANY ANNOUNCES PYLON BUZZ BLEND INDUCTED INTO THE ATHENS MUSIC WALK OF FAME NPR MUSIC EXPLORES PYLON’S LASTING INFLUENCE WITH UNRELEASED RECORDINGS “THE HUMAN BODY” & “3X3 (LIVE)” TODAY Seminal art-rock legends Pylon will release Pylon Box on November 6, 2020, via New West Records. The comprehensive 4xLP box set includes their studio albums Gyrate (1980) and Chomp (1983), which have been remastered from their original tapes and will be available on vinyl for the first time in nearly 35 years. Pylon Box includes 47 total tracks, 18 of which are previously unreleased recordings. In addition to the remastered studio albums, the collection also includes Pylon’s first ever recording, Razz Tape. The previously unreleased 13-track session predates the band’s legendary 1979 debut single “Cool” b/w “Dub.” Also included is Extra, an 11-song collection featuring a recording made before frontwoman Vanessa Briscoe Hay joined the band, along with the “Cool” b/w “Dub” single (which Rolling Stone named one of the “100 Greatest Debut Singles of All Time” this year), the rare recording “Recent Title,” the original single mix of “Crazy,” five previously unreleased studio and live recordings, and more. -

Murmur 25Th Anniversary Deluxe Edition Press Release

1 R.E.M.’S DEBUT ALBUM, THE GROUNDBREAKING MURMUR, REISSUED IN TWO-CD 25TH ANNIVERSARY DELUXE EDITION FEATURING PREVIOUSLY UNRELEASED 1983 CONCERT Alternative rock did not begin with a bang but with a Murmur. In 1983, a band from Athens, Georgia made its full- length album debut. The band was R.E.M.; the album was Murmur, Rolling Stone’s Album of the Year and one of the first alternative rock albums to gain mainstream notice. The two-CD 25th Anniversary Deluxe Edition of Murmur (I.R.S./UMe), released November 25, 2008, features that original landmark album remastered plus an additional disc with a previously unreleased concert recorded at Larry’s Hideaway in Toronto three months after Murmur’s April release. The 16-song live performance boasts nine of Murmur’s 12 songs, including “Radio Free Europe”; three songs first heard on 1982’s Chronic Town EP; early renditions of two songs that would subsequently appear on the band’s second album, 1984’s Reckoning; “Just A Touch,” later heard on R.E.M.’s fourth album, 1986’s Lifes Rich Pageant; and a cover of Velvet Underground’s “There She Goes Again,” which the group recorded in the studio for the b-side of “Radio Free Europe.” Assembled in conjunction with R.E.M., Murmur - Deluxe Edition, the package also includes exclusive essays providing insight into the recording of the album by producers Mitch Easter and Don Dixon, as well as former I.R.S. executives Jay Boberg, Sig Sigworth, Carlos Grasso, Michael Plen. Writes Dixon: “R.E.M. -

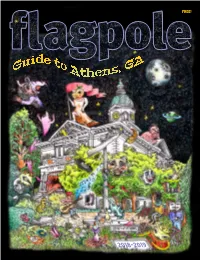

Guide to Athens, GA Flagpole.Com TABLE of CONTENTS

FREE! A G s, en e to Ath id u G 2018–2019 Celebrating 30 Years in Athens Eastside Downtown Timothy Rd. 706-369-0085 706-354-6966 706-552-1237 CREATIVE FOOD WITH A SOUTHERN ACCENT Athens Favorite Beer Selection Lunch Dinner Weekend Brunch and Favorite Fries (voted on by Flagpole Readers) Happy Hour: M-F 3-6pm Open for Lunch & Dinner 7 days a week & RESERVE YOUR TABLE NOW AT: Sunday Brunch southkitchenbar.com 247 E. Washington St. Trappezepub.com (inside historic Georgian Building) 269 N. Hull St. 706-395-6125 706-543-8997 2 2018–2019 flagpole Guide to Athens, GA flagpole.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Athens at a Glance . 4 Stage and Screen . 22 Annual Events . 9 Books and Records . 25 Athens Favorites . 11 Athens Music . .. 26 Lodging . 12 Farmers Markets and Food Trucks . 29 Art Around Town . 14 Athens and UGA Map . .31 Get Active . 17 Athens-Clarke County Map . 32 Parks and Recreation . 18 Restaurant, Bar and Club Index . 35 Specially for Kids 20 Restaurant and Bar Listings 38 . NICOLE ADAMSON UGA Homecoming Parade 2018–2019 flagpole Guide to Athens, GA Advertising Director & Publisher Alicia Nickles Instagram @flagpolemagazine Editor & Publisher Pete McCommons Twitter @FlagpoleMag Production Director Larry Tenner Managing Editor Gabe Vodicka Flagpole, Inc. publishes the Flagpole Guide to Athens every August Advertising Sales Representatives Anita Aubrey, Jessica and distributes 45,000 copies throughout the year to over 300 Pritchard Mangum locations in Athens, the University of Georgia campus and the Advertising Designer Anna LeBer surrounding area. Please call the Flagpole office or email class@ Contributors Blake Aued, Hillary Brown, Stephanie Rivers, Jessica flagpole.com to arrange large-quantity deliveries of the Guide. -

University News, October 2 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 10-2-1989 University News, October 2 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. 'S V! . l Free Money!!! Boise State, University October' 2, 1989 Volume X Issue Five Next tfme you're looking for a place to secure your bike, try the fo'untaln In front of the library. Some how, some way, a bike rack found Itsway Into the fountain. Hopefully, BSU bike thieves don't know . 'how to swim, Brown chooses BSU Students' by Rob'Gefzln families The University News invited BSU's music department hasa new concert band director. Marcel- to visit BSU lus Brown has only been working at BSU for about a month, having by Melanie Huffman moved to Boise from Moline, Ill., The University News where he was an instructor at Au- . gustana College. For the first time in 10 As part of his responsibilities years, BSU is sponsoring a , at the university; Brown will be Family Weckend. The event, directing BSU's concert band and which will take place Oct. 7-- . wind ensemble, teaching a funda- 8, was scheduled to occur Mqrcellus Brown in - mentals of music class, and giving conjunction with The Year of private lessons for both the trumpet the Student.