Chicago7 2019 Book FINAL Compressed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume II Number 3 (1920)

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Archives & Special Illinois Catholic Historical Review Collections 1920 Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume II Number 3 (1920) Illinois Catholic Historical Society Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/illinois_catholic_historical_review Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Illinois Catholic Historical Society, "Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume II Number 3 (1920)" (1920). Illinois Catholic Historical Review. 3. https://ecommons.luc.edu/illinois_catholic_historical_review/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Loyola University Chicago Archives & Special Collections at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Catholic Historical Review by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Illinois Catholic Historical Review Volume II JANUARY, 1920 Number 3 CONTENTS Reminiscences of Early Chicago Bedeiia Eehoe Ganaghan The Northeastern Part of the Diocese of St. Louis Under Bishop Rosati Bev. Jolm BotheBsteinei The Irish in Early Illinois Joseph J. Thompson The Chicago Catholic Institute and Chicago Lyceum Jolm Ireland Gallery- Father Saint Cyr, Missionary and Proto-Priest of Modern Chicago The Franciscans in Southern Illinois Bev. Siias Barth, o. F. m. A Link Between East and West Thomas f. Meehan The Beaubiens of Chicago Frank G. Beaubien A National Catholic Historical Society Founded Bishop Duggan and the Chicago Diocese George s. Phillips Catholic Churches and Institutions in Chicago in 1868 George S. Phillips Editorial Comment Annual Meeting of the Illinois Catholic Historical Society Book Reviews Published by the Illinois Catholic Historical Society 617 ASHLAND BLOCK, CHICAGO, ILL. -

Catholic Educational Exhibit Final Report, World's Columbian

- I Compliments of Brother /Tfcaurelian, f, S. C. SECRETARY AND HANAGER i Seal of the Catholic Educational Exhibit, World's Columbian Exposition, 1893. llpy ' iiiiMiF11 iffljy -JlitfttlliS.. 1 mm II i| lili De La Salle Institute, Chicago, III. Headquarters Catholic Educational Exhibit, World's Fair, 1S93. (/ FINAL REPORT. Catholic Educational Exhibit World's Columbian Exposition Ctucaofo, 1893 BY BROTHER MAURELIAN F. S. C, Secretary and Manager^ TO RIGHT REVEREND J. L. SPALDING, D. D., Bishop of Peoria and __-»- President Catholic Educational ExJiibit^ WopIgT^ F^&ip, i8qt I 3 I— DC X 5 a a 02 < cc * 5 P3 2 <1 S w ^ a o X h c «! CD*" to u 3* a H a a ffi 5 h a l_l a o o a a £ 00 B M a o o w a J S"l I w <5 K H h 5 s CO 1=3 s ^2 o a" S 13 < £ a fe O NI — o X r , o a ' X 1 a % a 3 a pl. W o >» Oh Q ^ X H a - o a~ W oo it '3 <»" oa a? w a fc b H o £ a o i-j o a a- < o a Pho S a a X X < 2 a 3 D a a o o a hJ o -^ -< O O w P J tf O - -n>)"i: i i'H-K'i4ui^)i>»-iii^H;M^ m^^r^iw,r^w^ ^-Trww¥r^^^ni^T3r^ -i* 3 Introduction Letter from Rig-lit Reverend J. Ij. Spalding-, D. D., Bishop of Peoria, and President of the Catholic Educational Exhibit, to Brother Maurelian, Secretary and Manag-er. -

El Paso and the Twelve Travelers

Monumental Discourses: Sculpting Juan de Oñate from the Collected Memories of the American Southwest Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät IV – Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften – der Universität Regensburg wieder vorgelegt von Juliane Schwarz-Bierschenk aus Freudenstadt Freiburg, Juni 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Udo Hebel Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Volker Depkat CONTENTS PROLOGUE I PROSPECT 2 II CONCEPTS FOR READING THE SOUTHWEST: MEMORY, SPATIALITY, SIGNIFICATION 7 II.1 CULTURE: TIME (MEMORY) 8 II.1.1 MEMORY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 9 II.2 CULTURE: SPATIALITY (LANDSCAPE) 13 II.2.1 SPATIALITY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 14 II.3 CULTURE: SIGNIFICATION (LANDSCAPE AS TEXT) 16 II.4 CONCEPTUAL CONVERGENCE: THE SPATIAL TURN 18 III.1 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: PLACE – SPACE – LANDSCAPE III.1.1 PLACE 21 III.1.2 SPACE 22 III.1.3 LANDSCAPE 23 III.2 EMPLACEMENT AND EMPLOTMENT 25 III.3 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: SITE – MONUMENT – LANDSCAPE III.3.1 SITES OF MEMORY 27 III.3.2 MONUMENTS 30 III.3.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY 32 IV SPATIALIZING AMERICAN MEMORIES: FRONTIERS, BORDERS, BORDERLANDS 34 IV.1 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY I: THE LAND OF ENCHANTMENT 39 IV.1.1 THE TRI-ETHNIC MYTH 41 IV.2 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY II: HOMELANDS 43 IV.2.1 HISPANO HOMELAND 44 IV.2.2 CHICANO AZTLÁN 46 IV.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY III: BORDER-LANDS 48 V FROM THE SOUTHWEST TO THE BORDERLANDS: LANDSCAPES OF AMERICAN MEMORIES 52 MONOLOGUE: EL PASO AND THE TWELVE TRAVELERS 57 I COMING TO TERMS WITH EL PASO 60 I.1 PLANNING ‘THE CITY OF THE NEW OLD WEST’ 61 I.2 FOUNDATIONAL -

" a Great and Lasting Beginning": Bishop John Mcmullen's

22 Catholic Education/June 2005 ARTICLES “A GREAT AND LASTING BEGINNING”: BISHOP JOHN MCMULLEN’S EDUCATIONAL VISION AND THE FOUNDING OF ST. AMBROSE UNIVERSITY GEORGE W. MCDANIEL St. Ambrose University Catholic education surfaces as a focus and concern in every age of the U.S. Catholic experience. This article examines the struggles in one, small Midwestern diocese surrounding the establishment and advancement of Catholic education. Personal rivalries, relationship with Rome, local politics, finances, responding to broader social challenges, and the leadership of cler- gy were prominent themes then, as they are now. Numerous historical insights detailed here help to explain the abiding liberal character of Catholicism in the Midwestern United States. n the spring of 1882, Bishop John McMullen, who had been in the new IDiocese of Davenport for about 6 months, met with Father Henry Cosgrove, the pastor of St. Marguerite’s (later Sacred Heart) Cathedral. “Where shall we find a place to give a beginning to a college?” McMullen asked. Cosgrove’s response was immediate: “Bishop, I will give you two rooms in my school building.” “All right,” McMullen said, “let us start at once” (The Davenport Democrat, 1904; Farrell, 1982, p. iii; McGovern, 1888, p. 256; Schmidt, 1981, p. 111). McMullen’s desire to found a university was not as impetuous as it may have seemed. Like many American Catholic leaders in the 19th century, McMullen viewed education as a way for a growing immigrant Catholic population to advance in their new country. Catholic education would also serve as a bulwark against the encroachment of Protestant ideas that formed the foundation of public education in the United States. -

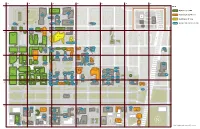

KEY KEY Last Updated: June 15, 2020

Friend Family Health Center Ronald McDonald House A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST KEY 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Building is OPEN Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S Building is COMPLETE AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Building is IN-USE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - DATE EXPECTED READY DATE AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S KIMBARK AVE S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer CollegiumJUNE 19 Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - -

Insider's Guide

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu VALOIS RESTAURANT 1518 E. 53rd St. insider’s valoisrestaurant.com President Obama’s favorite breakfast spot! They serve classic soul food for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Get guide this: they serve breakfast all day! If you forget cash for this cash-only establishment, worry not, there is an ATM Have you ever wondered what Hyde Park does inside. for fun? Sure you have! For a true taste of Hyde Park and its surrounding neighborhoods, check ORIENTAL INSTITUTE LIBRARY 1155 E. 58th St. out these not-to-be-missed South Side gems. Although Harper Memorial Library tends to attract more PROMONTORY POINT tourists and studiers alike, the Oriental Institute is home to 5491 S. South Shore Dr. a smaller, but just as beautiful reading room. Once inside, chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/Burnham-Park/ head up the stone steps to the second floor and take a If you are looking for a great view of the lake and the right. Open 10am-5pm. Chicago skyline, or maybe just a calming place to sit and read, Promontory Point is the site to visit. A great UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUB destination for picnics, sunsets, and people-watching, 1212 E. 59th St. “The Point” is located on Chicago’s Lake Front Trail, which Ida Noyes Hall, lower level stretches south to 95th Street and all the way north to leadership.uchicago.edu/orcsas-pub Navy Pier. Long gone are the days of indoor smoking and 50-cent cans of PBR, but “The Pub,” as it’s known on campus, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CAMPUS BOTANY maintains its status as a reliably fun place for students and botanicgarden.uchicago.edu faculty alike. -

Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-8-2007 Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L. Black University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Black, Hope L., "Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer by Hope L. Black A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida CoMajor Professor: Gary Mormino, Ph.D. CoMajor Professor: Raymond Arsenault, Ph.D. Julie Armstrong, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 8, 2007 Keywords: World’s Columbian Exposition, Meadowsweet Pastures, Great Chicago Fire, Manatee County, Seaboard Air Line Railroad © Copyright 2007, Hope L. Black Acknowledgements With my heartfelt appreciation to Professors Gary Mormino and Raymond Arsenault who allowed me to embark on this journey and encouraged and supported me on every path; to Greta ScheidWells who has been my lifeline; to Professors Julie Armstrong, Christopher Meindl, and Daryl Paulson, who enlightened and inspired me; to Ann Shank, Mark Smith, Dan Hughes, Lorrie Muldowney and David Baber of the Sarasota County History Center who always took the time to help me; to the late Rollins E. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS September 23, 1969 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

26744 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 23, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CHANGING CHALLENGE IN HIGH centrated on the execution of the Interstate assessing the impact of land use of highway WAY DEVELOPMENT STRESSED highway program. Before we have completed construction, urban redevelopment, mining BY SENATOR RANDOLPH IN AD it sometime in the middle of the next dec and sanitary landfills. We are looking at the DRESS AT VIRGINIA MOTOR VE ade we will have spent approximately $70 bil question of biological imbalances created by lion on this massive public works under dredging, thermal pollution, pesticides, and HICLE CONFERENCE taking, begun 48 years ago. By then we will air pollution. And we are probing problems have achieved our goal of connecting every connected with flooding and dam construc major metropolitan center in the United tion, the effects of building reservoirs, and HON. WILLIAM B. SPONG, JR. States in a coast-to-coast and border-to the use of nuclear energy for power or con OF VIRGINIA border hook-up. struction. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES In the process of building our 42,500 miles The heart of our concern is best reflected in of Interstate and Defense highways, we will Tuesday, September 23, 1969 legislation introduced early this year by have produced vast wealth in the form of myself and 41 of my colleagues, the "En Mr. SPONG. Mr. President, this morn new homes, new plants, and new jobs. We vironmental Quality Improvement Act of ing the Virginia Motor Vehicle Confer will have repeated many times over the suc 1969," which has been incorporated in S. -

2012 Appropriation Ordinance 10.27.11.Xlsx

2012 Budget Appropriations 3 4 Table of Contents Districtwide 8 Humboldt Park……………...…....………….…… 88 Districtwide Summary 9 Kedvale Park……………...…....………….…….. 90 Communications……………….....….……...….… 10 Kelly (Edward J.) Park……………...…....……91 Community Recreation ……………..……………. 11 Kennicott Park……………...…....………….…… 92 Facilities Management - Specialty Trades……………… 29 Kenwood Community Park……………...…. 93 Grant Park Music Festival………...……….…...… 32 La Follette Park……………...…....………….…… 94 Human Resources…………..…….…………....….. 33 Lake Meadows Park ……………...…....………96 Natural Resources……………….……….……..….. 34 Lakeshore……………...…....………….…….. 97 Park Services - Permit Enforcement 38 Le Claire-Hearst Community Center……… 98 Madero School Park……………...…....……… 99 Central Region 40 McGuane Park……………...…....………….…… 100 Central Region Parks 41 McKinley Park……………………………....…… 103 Central Region – Summary ...……...……................. 43 Moore Park……………...…....………….…….. 105 Central Region – Administration……….................... 44 National Teachers Academy……………...… 106 Altgeld Park………………………………………… 46 Northerly Island……………...…....………….… 108 Anderson Playground Park……….……...………….. 47 Orr Park………………………………..…..…..… 109 Archer Park……...................................................... 48 Piotrowski Park……………...…....………….… 110 Armour Square Park……........................................... 49 Pulaski Park……………...…....………….…….. 113 Augusta Playground……........................................... 50 Seward Park ……………...…....………….…….. 114 Austin Town Hall……............................................... -

INTERVIEW with PAUL DURBIN Mccurry Interviewed by Betty J. Blum Compiled Under the Auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral Histo

INTERVIEW WITH PAUL DURBIN McCURRY Interviewed by Betty J. Blum Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project The Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings Department of Architecture The Art Institute of Chicago Copyright © 1988 Revised Edition Copyright © 2005 The Art Institute of Chicago This manuscript is hereby made available to the public for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publication, are reserved to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of The Art Institute of Chicago. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of The Art Institute of Chicago. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv Preface to the Revised Edition vi Outline of Topics vii Oral History 1 Selected References 150 Curriculum Vitae 151 Index of Names and Buildings 152 iii PREFACE On January 23, 24, and 25, 1987, I met with Paul McCurry in his home in Lake Forest, Illinois, where we recorded his memoirs. During Paul's long career in architecture he has witnessed events and changes of prime importance in the history of architecture in Chicago of the past fifty years, and he has known and worked with colleagues, now deceased, of major interest and significance. Paul retains memories dating back to the 1920s which give his recollections and judgments special authority. Moreover, he speaks as both an architect and an educator. Our recording sessions were taped on four 90-minute cassettes that have been transcribed, edited and reviewed for clarity and accuracy. This transcription has been minimally edited in order to maintain the flow, spirit and tone of Paul's original thought. -

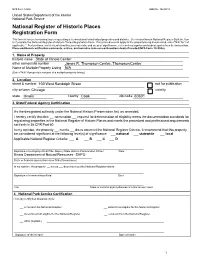

Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" If Property Is Not Part of a Multiple Property Listing)

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name State of Illinois Center other names/site number James R. Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 100 West Randolph Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Department of Natural Resources - SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Pennsylvania Avenue Cultural Landscape Inventory

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Pennsylvania Avenue, NW-White House to the Capitol National Mall and Memorial Parks-L’Enfant Plan Reservations May 10, 2016 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW-White House to the Capitol National Mall and Memorial Parks-L’Enfant Plan Reservations Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan ............................................................................................ Page 3 Concurrence Status ...................................................................................................................... Page 10 Geographic Information & Location Map ................................................................................... Page 11 Management Information ............................................................................................................. Page 12 National Register Information ..................................................................................................... Page 13 Chronology & Physical History ................................................................................................... Page 24 Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity .............................................................................................. Page 67 Condition Assessment .................................................................................................................. Page 92 Treatment ....................................................................................................................................