Mcintyre Umd 0117N 15724.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World in Focus 15

I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y http://www.tehrantimes.com/international OOCTOBERCTOBER 228,8, 22012012 WORLD IN FOCUS 15 By Kourosh Ziabari own reasons like that. What do you think about the mis- rench journalist Thierry Meyssan sion of Kofi Annan? Was it successful? Fsays Al-Qaeda and NATO are overtly You had written in one of your articles COMMENT cooperating with each other to desta- that he had predicted the overthrow- bilize Syria, and that Israel, France, Al-Qaeda-NATO ing of the government of President Tehran to finance Qatar and the United States are ben- Assad. Since it didn’t happen, he re- Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline efiting from the continued crisis in the nexus destabilizing signed. Is this true? Arab country. Yes, actually Kofi Annan was the Contd. from P. 1 “At the beginning [of violence in architect of the agreement of Geneva. Syria], people from Al-Qaeda commit- Syria, Thierry You remember that Russians had tried German-based firm ILF has completed engineering de- ted horrible crimes like what they did to organize a big peace conference in sign of the pipeline and an interim feasibility report has in Libya and Iraq and now they are car- Meyssan says Moscow, but the U.S. stalled that, be- put the project cost between $1.2 and $1.5 billion. rying out suicide attacks. According to cause they didn’t want to have talks “If the project gets under way with the participation Council on Foreign Relations, that is, with Iran. -

School Breaks Ground on Multi-Purpose Athletic Field with Lights Achievement • Spring 2018 1 Achievement Spring 2018

Spring 2018 Achievement Asheville School Alumni Magazine School Breaks Ground On Multi-Purpose Athletic Field With Lights Achievement • Spring 2018 1 Achievement Spring 2018 BOARD OF TRUSTEES An Education For An Inspired Life Published for Alumni & Mr. Walter G. Cox Jr. 1972, Chairman P ‘06 Friends of Asheville School Ms. Ann Craver, Co-Vice Chair P ‘11 by the Advancement Department Asheville School Mr. Robert T. Gamble 1971, Co-Vice Chair 360 Asheville School Road Asheville, North Carolina 28806 Mr. Marshall T. Bassett 1972, Treasurer 828.254.6345 Dr. Audrey Alleyne P ’18, ’19 www.ashevilleschool.org (Ex officio Parents’ Association) Editor Mr. Haywood Cochrane Jr. P ’17 Bob Williams Mr. Thomas E. Cone 1972 Assistant Head of School for Advancement Dan Seiden Mr. Matthew S. Crawford 1984 Writers Mr. D. Tadley DeBerry 1981 Alex Hill Tom Marberger 1969 Mr. James A. Fisher 1964 Travis Price Bob Williams Dr. José A. González 1985 P ’20 Proof Readers Ms. Mary Robinson Hervig 2002 Tish Anderson Bob Williams Ms. Jean Graham Keller 1995 Travis Price Mr. Richard J. Kelly 1968 P ’20 Printing Mr. Nishant N. Mehta 1998 Lane Press Mr. Archibald R. Montgomery IV Photographers Blake Madden (Ex officio Head of School) Sheila Coppersmith Eric Frazier Dr. Gregory K. Morris 1972 Bob Williams Mr. J. Allen Nivens Jr. 1993 A special thanks to the 1923 Memorial Archives for providing many of the archival photographs (Ex officio Alumni Association) in this edition. Ms. Lara Nolletti P ’19 Mr. Laurance D. Pless 1971 P ’09, P ’13 Asheville School Mission: To prepare our students for college and for life Mr. -

Lecture Misinformation

Quote of the Day: “A lie will go round the world while truth is pulling its boots on.” -- Baptist preacher Charles H. Spurgeon, 1859 Please fill out the course evaluations: https://uw.iasystem.org/survey/233006 Questions on the final paper Readings for next time Today’s class: misinformation and conspiracy theories Some definitions of fake news: • any piece of information Donald Trump dislikes more seriously: • “a type of yellow journalism or propaganda that consists of deliberate disinformation or hoaxes spread via traditional news media (print and broadcast) or online social media.” disinformation: “false information which is intended to mislead, especially propaganda issued by a government organization to a rival power or the media” misinformation: “false or inaccurate information, especially that which is deliberately intended to deceive” Some findings of recent research on fake news, disinformation, and misinformation • False news stories are 70% more likely to be retweeted than true news stories. The false ones get people’s attention (by design). • Some people inadvertently spread fake news by saying it’s false and linking to it. • Much of the fake news from the 2016 election originated in small-time operators in Macedonia trying to make money (get clicks, sell advertising). • However, Russian intelligence agencies were also active (Kate Starbird’s research). The agencies created fake Black Lives Matter activists and Blue Lives Matter activists, among other profiles. A quick guide to spotting fake news, from the Freedom Forum Institute: https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org/first-amendment- center/primers/fake-news-primer/ Fact checking sites are also essential for identifying fake news. -

What Is the Function of Confirmation Bias?

Erkenntnis https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-020-00252-1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH What Is the Function of Confrmation Bias? Uwe Peters1,2 Received: 7 May 2019 / Accepted: 27 March 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Confrmation bias is one of the most widely discussed epistemically problematic cognitions, challenging reliable belief formation and the correction of inaccurate views. Given its problematic nature, it remains unclear why the bias evolved and is still with us today. To ofer an explanation, several philosophers and scientists have argued that the bias is in fact adaptive. I critically discuss three recent proposals of this kind before developing a novel alternative, what I call the ‘reality-matching account’. According to the account, confrmation bias evolved because it helps us infuence people and social structures so that they come to match our beliefs about them. This can result in signifcant developmental and epistemic benefts for us and other people, ensuring that over time we don’t become epistemically disconnected from social reality but can navigate it more easily. While that might not be the only evolved function of confrmation bias, it is an important one that has so far been neglected in the theorizing on the bias. In recent years, confrmation bias (or ‘myside bias’),1 that is, people’s tendency to search for information that supports their beliefs and ignore or distort data contra- dicting them (Nickerson 1998; Myers and DeWall 2015: 357), has frequently been discussed in the media, the sciences, and philosophy. The bias has, for example, been mentioned in debates on the spread of “fake news” (Stibel 2018), on the “rep- lication crisis” in the sciences (Ball 2017; Lilienfeld 2017), the impact of cognitive diversity in philosophy (Peters 2019a; Peters et al. -

Your Journey Is Loading. Scroll Ahead to Continue

Your journey is loading. Scroll ahead to continue. amizade.org • @AmizadeGSL Misinformation and Disinformation in the time of COVID-19 | VSL powered by Amizade | amizade.org 2 Welcome! It is with great pleasure that Amizade welcomes you to what will be a week of learning around the abundance of misinformation and disinformation in both the traditional media as well as social media. We are so excited to share this unique opportunity with you during what is a challenging time in human history. We have more access to information and knowledge today than at any point in human history. However, in our increasingly hyper-partisan world, it has become more difficult to find useful and accurate information and distinguish between what is true and false. There are several reasons for this. Social media has given everyone in the world, if they so desire, a platform to spread information throughout their social networks. Many websites, claiming to be valid sources of news, use salacious headlines in order to get clicks and advertising dollars. Many “legitimate” news outlets skew research and data to fit their audiences’ political beliefs. Finally, there are truly bad actors, intentionally spreading false information, in order to sow unrest and further divide people. It seems that as we practice social distancing, connecting with the world has become more important than ever before. At the same time, it is exceedingly important to be aware of the information that you are consuming and sharing so that you are a part of the solution to the ongoing flood of false information. This program’s goal is to do just that—to connect you with the tools and resources you need to push back when you come across incorrect or intentionally misleading information, to investigate your own beliefs and biases, and to provide you with the tools to become a steward of good information. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) ...And the pursuit of national health : the incremental strategy toward national health insurance in the United States of America Kooijman, J.W. Publication date 1999 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kooijman, J. W. (1999). ...And the pursuit of national health : the incremental strategy toward national health insurance in the United States of America. Rodopi. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 V: ENACTING MEDICARE AND MEDICAID After eight years of a Republican administration, the Democrats were looking for a political issue that could bring the Democrats back in the White House. Medicare provided a perfect opportunity for liberal Democrats to rekindle the spirit of the New Deal and Fair Deal. -

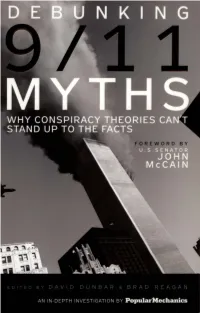

Debunking 911 Myths.Pdf

PRAISE FOR DEBUNKING 9111 MYTHS "Debunking 9111 Myths is a reliable and rational answer to the many fanciful conspiracy theories about 9/11. Despite the fact that the myths are fictitious, many have caught on with those who do not trust their government to tell the truth anymore. Fortunately, the govern ment is not sufficiently competent to pull off such conspiracies and too leaky to keep them secret. What happened on 9/11 has been well established by the 9/11 Commission. What did not happen has now been clearly explained by Popular Mechanics." -R 1 cHARD A. cLARKE, former national security advisor, author of Against All Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror "This book is a victory for common sense; 9/11 conspiracy theorists beware: Popular Mechanics has popped your paranoid bubble world, using pointed facts and razor-sharp analysis." -Au s T 1 N BAY, national security columnist (Creators Syndicate), author (with James F. Dunnigan) of From Shield to Storm: High-Tech Weapons, Military Strategyand Coalition Warfare in the Persian Gulf "Even though I study weird beliefs for a living, I never imagined that the 9/11 conspiracy theories that cropped up shortly after that tragic event would ever get cultural traction in America, but here we are with a plethora of conspiracies and no end in sight. What we need is a solid work of straightforward debunking, and now we have it in Debunking 9111 Myths. The Popular Mechanics article upon which the book is based was one of the finest works of investigative journalism and skep tical analysis that I have ever encountered, and the book-length treat ment of this codswallop will stop the conspiracy theorists in their fantasy-prone tracks. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Ascertainment Report Jul-Aug-Sept 2009

Quarterly Programming Report June - September 2009 KPCC / KPCV / KUOR Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration 7/1/09 SAC Lawmakers miss budget deadline, Controller to begin issuing IOUs CC :13 7/1/09 LAW LAPD Officers disciplined for involvement in May Day Melee Julian :48 7/1/09 SAC New budget year began at midnight, no budget deal in place Myers 3:37 7/1/09 SAC Lawmakers fail to pass budget that could have kept CA from issuing IOUs Small 2:40 7/1/09 POLI Mayor sworn in today Stoltze 4:34 7/1/09 POLI Frank Stoltze on Mayor Villaraigosa's second inaugural Stoltze :60 7/1/09 POLI Frank Stoltze on Mayor Villaraigosa's second inaugural Stoltze 1:09 7/1/09 SAC Governor declares fiscal emergency CC :22 7/1/09 ART LACMA's tight budget means fewer touring exhibitions in town CC :26 7/1/09 SAC Governor declares fiscal emergency, urges banks to accept IOUs CC :16 7/1/09 EDU Birmingham High School seeks charter status CC :25 7/1/09 LAW LAPD will not fire officers for diciplinary breaches in MacArthur Park incident CC :11 7/1/09 IE Riverside County fire officials issue fireworks warning to residents CC :21 7/1/09 HEAL Watchdog group sues state agency over care for kids with autism CC :18 7/1/09 POLI Frank Stoltze on Mayor Villaraigosa's second inaugural Stoltze 1:12 7/1/09 POLI State assembly speaker laments that there's no budget deal yet CC :22 7/1/09 POLI California assembly speaker tries to explain the budget debacle CC :26 7/1/09 POLI Alex Cohen talks with Julie Small about latest on budget, IOUs Small 4:20 7/1/09 ARTS Marc Haefele talks -

Chasing Success

AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE Chasing Success Air Force Efforts to Reduce Civilian Harm Sarah B. Sewall Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dr. Ernest Allan Rockwell Sewall, Sarah B. Copy Editor Carolyn Burns Chasing success : Air Force efforts to reduce civilian harm / Sarah B. Sewall. Cover Art, Book Design and Illustrations pages cm L. Susan Fair ISBN 978-1-58566-256-2 Composition and Prepress Production 1. Air power—United States—Government policy. Nedra O. Looney 2. United States. Air Force—Rules and practice. 3. Civilian war casualties—Prevention. 4. Civilian Print Preparation and Distribution Diane Clark war casualties—Government policy—United States. 5. Combatants and noncombatants (International law)—History. 6. War victims—Moral and ethical aspects. 7. Harm reduction—Government policy— United States. 8. United States—Military policy— Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. II. Title: Air Force efforts to reduce civilian harm. UG633.S38 2015 358.4’03—dc23 2015026952 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Director and Publisher Allen G. Peck Published by Air University Press in March 2016 Editor in Chief Oreste M. Johnson Managing Editor Demorah Hayes Design and Production Manager Cheryl King Air University Press 155 N. Twining St., Bldg. 693 Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6026 [email protected] http://aupress.au.af.mil/ http://afri.au.af.mil/ Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the organizations with which they are associated or the views of the Air Force Research Institute, Air University, United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or any AFRI other US government agency. -

Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective: Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People”

Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People A Collection of Papers from an International Conference held in Tokyo, May 2015 “Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective: Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People” A Collection of Papers from an International Conference held in Tokyo, May 2015, organized jointly by the Japan Studies Association of Canada (JSAC), the Japanese Association for Canadian Studies (JACS) and the Japan-Canada Interdisciplinary Research Network on Gender, Diversity and Tohoku Reconstruction (JCIRN). Edited by David W. Edgington (University of British Columbia), Norio Ota (York University), Nobuyuki Sato (Chuo University), and Jackie F. Steele (University of Tokyo) © 2016 Japan Studies Association of Canada 1 Table of Contents List of Tables................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4 List of Contributors ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Editors’ Preface ............................................................................................................................................. 7 SECTION A: ECONOMICS AND POLITICS IN JAPAN .......................................................................... -

The Ground Zero Mosque Controversy: Implications for American Islam

Religions 2011, 2, 132-144; doi:10.3390/rel2020132 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article The Ground Zero Mosque Controversy: Implications for American Islam Liyakat Takim Sharjah Chair in Global Islam, McMaster University, University Hall, 116, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4K1, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1 (647) 865 7863 Received: 29 March 2011; in revised form: 22 May 2011 / Accepted: 31 May 2011 / Published: 7 June 2011 Abstract: The controversy surrounding the “ground zero mosque” is part of a larger debate about the place of Islam in U.S. public space. The controversy also reveals the ways in which the boundaries of American identity continue to be debated, often through struggles over who counts as a “real” American. It further demonstrates the extent to which Islam is figured as un-American and militant, and also the extent to which all Muslims are required to account for the actions of those who commit violence under the rubric of Islam. This paper will discuss how, due to the events of September 11, 2001, Muslims have engaged in a process of indigenizing American Islam. It will argue that the Park51 Islamic Community Center (or Ground Zero mosque) is a reflection of this indigenization process. It will go on to argue that projects such as the Ground Zero mosque which try to establish Islam as an important part of the American religious landscape and insist on the freedom of worship as stated in the U.S. constitution, illustrate the ideological battlefield over the place of Islam in the U.S.