The Folktale and Its Utopian Function in "As Easy As A.B.C.'' by Rudyard Kipling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Once Upon a Time There Was a Puss in Boots: Hanna Januszewska’S Polish Translation and Adaptation of Charles Perrault’S Fairy Tales

Przekładaniec. A Journal of Literary Translation 22–23 (2009/2010): 33–55 doi:10.4467/16891864ePC.13.002.0856 Monika Woźniak ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS A PUSS IN BOOTS: Hanna Januszewska’s POLISH TRANSLATION AND ADAPTATION OF CHARLES Perrault’s FAIRY TALES Abstract: This article opens with an overview of the Polish reception of fairy tales, Perrault’s in particular, since 1700. The introductory section investigates the long- established preference for adaptation rather than translation of this genre in Poland and provides the framework for an in-depth comparative analysis of the first Polish translation of Mother Goose Tales by Hanna Januszewska, published in 1961, as well as her adaptation of Perrault’s tales ten years later. The examination focuses on two questions: first, the cultural distance between the original French text and Polish fairy- tales, which causes objective translation difficulties; second, the cultural, stylistic and linguistic shifts introduced by Januszewska in the process of transforming her earlier translation into a free adaptation of Perrault’s work. These questions lead not only to comparing the originality or literary value of Januszewska’s two proposals, but also to examining the reasons for the enormous popularity of the adapted version. The faithful translation, by all means a good text in itself, did not gain wide recognition and, if not exactly a failure, it was nevertheless an unsuccessful attempt to introduce Polish readers to the original spirit of Mother Goose Tales. Keywords: translation, adaptation, fairy tale, Perrault, Januszewska The suggestion that Charles Perrault and his fairy tales are unknown in Poland may at first seem absurd, since it would be rather difficult to im- agine anyone who has not heard of Cinderella, Puss in Boots or Sleeping Beauty. -

British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932

British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932 CROMPTON, Teresa Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24737/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version CROMPTON, Teresa (2014). British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918- 1932. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam Universiy. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932 Teresa Crompton A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2014 Abstract The thesis examines the development of the civil air route between Britain and India from 1918 to 1932. Although an Indian route had been pioneered before the First World War, after it ended, fourteen years would pass before the route was established on a permanent basis. The research provides an explanation for the late start and subsequent slow development of the India route. The overall finding is that progress was held back by a combination of interconnected factors operating in both Britain and the Persian Gulf region. These included economic, political, administrative, diplomatic, technological, and cultural factors. The arguments are developed through a methodology that focuses upon two key theoretical concepts which relate, firstly, to interwar civil aviation as part of a dimension of empire, and secondly, to the history of aviation as a new technology. -

MX), Washington, D.C

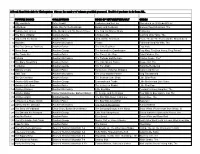

ED 347 505 CS 010 978 TITLE From Tales of the Tongue to Tales of the Pen: An Organic Approach to Children's Literature. Resource Guide. NEM 1989 Summer Institute. INSTITUTION Southwest Texas State Univ., San Marcos. Dept. of English. SPONS AGENC: National Endowment for the Humanities (MX), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 89 CONTRACT ES-21656-89 NOTE 233p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; *Fairy Tales; *Folk Culture; Institutes (Training Programs); Lesson Plans; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Mythology; Summer Programs; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Folktales; Odyssey; Southwest Texas State University ABSTRACT Developed from the activities of a summer institute in Texas that focused on "The Odyssey," folk andfairy tale, and folk rhyme, this resource guide presents 50 lesson plansoffering a variety of approaches to teaching mythology andfolklore to elementary school students. The lesson plans presented inthe resource guide share a common foundation inarchetypes and universal themes that makes them adaptable to and useful invirtually any elementary school setting. The 13 lesson plans in the firstchapter deal with on "The Odyssey." The 25 lesson plans inthe second chapter deal with folk and fairy tale (stories are ofEuropean, American Indian, African, Mexican American, and Japanesederivation; two units are specifically female-oriented).The 12 lesson plans in the third chapter encompass folk rhymes (most are from MotherGoose). The fourth chapter presents a scope and sequencedesigned to give librarians a sequential guideline and appropriateactivities for introducing and teaching mytAology, folk and fairytales, and nursery rhymes. Each lesson plan typically includes:author of plan; intended grade level; time frame clays and length of individual sessions); general information about the unit; materialsneeded; and a list of activities. -

The Significance of the Numbers Three, Four, and Seven in Fairy Tales, Folklore, And

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Honors Projects Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice 2014 The iS gnificance of the Numbers Three, Four, and Seven in Fairy Tales, Folklore, and Mythology Alonna Liabenow Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Liabenow, Alonna, "The iS gnificance of the Numbers Three, Four, and Seven in Fairy Tales, Folklore, and Mythology" (2014). Honors Projects. 418. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/418 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liabenow 1 Alonna Liabenow HNR 499 Senior Project Final The Significance of the Numbers Three, Four, and Seven in Fairy Tales, Folklore, and Mythology INTRODUCTION “Once upon a time … a queen was sitting and sewing by a window with an ebony frame. While she was sewing, she looked out at the snow and pricked her finger with the needle. Three drops of blood fell onto the snow” (Snow White 81). This is a quote which many may recognize as the opening to the famous fairy tale Snow White. But how many would take notice of the number three in the last sentence of the quote and question its significance? Why, specifically, did three drops of blood fall from the queen’s finger? The quote from Snow White is just one example of many in which the number three presents itself as a significant part of the story. -

Some Political Implications in the Works of Rudyard Kipling

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1946 Some Political Implications in the Works of Rudyard Kipling Wendelle M. Browne Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Browne, Wendelle M., "Some Political Implications in the Works of Rudyard Kipling" (1946). Master's Theses. 74. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/74 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1946 Wendelle M. Browne SOME POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS IN THE WORKS OF RUDYARD KIPLING by Wendelle M. Browne A Thesis Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University May 1946 VITA Wendelle M. Browne was born in Chicago, Illinois, March 2£, 1913. She was graduated from the Englewood High School, Chicago, Illinois, June, 1930 and received a teaching certificate from The Chicago Normal College in June 1933. The Bachelor of Science Degree in the depart~ent of Education was conferred by the University of Illinois in June, 1934. From 1938 to the present time the writer has been engaged as a teacher in the elementary schools of Chicago. During the past five years she has devoted herself to graduate study in English at Loyola University in Chicago. -

Level 3-9 Diamonds and Toads

Level 3-9 Diamonds and Toads Workbook Teacher’s Guide and Answer Key 1 Teacher’s Guide A. Summary 1. Book Summary Diamonds and Toads is a story about a proud and cruel woman with two daughters. One daughter is kind, and the other is rude. The younger daughter is kind and polite. She works very hard. The older daughter is rude and unkind. She acts just like her mother. Every day, the younger daughter goes to the river to get water. One day, an old lady asks the girl for a drink. The girl washes the lady’s jug and fills it with clean water. The old lady is a fairy. She gives the girl a gift. When she talks, good things will fall from her mouth. The girl gets home late. Her mother is angry. The girl opens her mouth to talk, and the mother is surprised. Flowers and jewels fall from the girl’s mouth as she speaks. The mother tells the older daughter to go to the river. She wants the older daughter to get a gift from the fairy, too. The older daughter goes to the river. This time, the fairy pretends to be a beautiful lady instead of an old woman. The older daughter is rude to her. She tells her to get her own water. The fairy gives her a gift. When she talks, bad things will fall from her mouth. Toads and snakes fall out of the older duaghter’s mouth when she speaks! When the mother sees what happens, she blames the younger daughter. -

Once Upon a Time There Was a Puss in Boots: Hanna Januszewska's Polish Translation and Adaptation of Charles Perrault's Fair

Przekładaniec. A Journal of Literary Translation 22–23 (2009/2010): 33–55 doi:10.4467/16891864ePC.13.002.0856 Monika Woźniak ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS A PUSS IN BOOTS: Hanna Januszewska’s POLISH TRANSLATION AND ADAPTATION OF CHARLES Perrault’s FAIRY TALES Abstract: This article opens with an overview of the Polish reception of fairy tales, Perrault’s in particular, since 1700. The introductory section investigates the long- established preference for adaptation rather than translation of this genre in Poland and provides the framework for an in-depth comparative analysis of the first Polish translation of Mother Goose Tales by Hanna Januszewska, published in 1961, as well as her adaptation of Perrault’s tales ten years later. The examination focuses on two questions: first, the cultural distance between the original French text and Polish fairy- tales, which causes objective translation difficulties; second, the cultural, stylistic and linguistic shifts introduced by Januszewska in the process of transforming her earlier translation into a free adaptation of Perrault’s work. These questions lead not only to comparing the originality or literary value of Januszewska’s two proposals, but also to examining the reasons for the enormous popularity of the adapted version. The faithful translation, by all means a good text in itself, did not gain wide recognition and, if not exactly a failure, it was nevertheless an unsuccessful attempt to introduce Polish readers to the original spirit of Mother Goose Tales. Keywords: translation, adaptation, fairy tale, Perrault, Januszewska The suggestion that Charles Perrault and his fairy tales are unknown in Poland may at first seem absurd, since it would be rather difficult to im- agine anyone who has not heard of Cinderella, Puss in Boots or Sleeping Beauty. -

Mt Void 2073

MT VOID 06/28/19 -- Vol. 37, No. 52, Whole Number 2073 file:///Users/markleeper/mtvoid/VOID0628.htm MT VOID 06/28/19 -- Vol. 37, No. 52, Whole Number 2073 @@@@@ @ @ @@@@@ @ @ @@@@@@@ @ @ @@@@@ @@@@@ @@@ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @@@@@ @@@@ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @@@@@ @ @ @ @ @@@@@ @@@@@ @@@ Mt. Holz Science Fiction Society 06/28/19 -- Vol. 37, No. 52, Whole Number 2073 Table of Contents Science Fiction (and Other) Discussion Groups, Films, Lectures, etc. (NJ) My Picks for Turner Classic Movies for July (comments by Mark R. Leeper and Evelyn C. Leeper) THE CALCULATING STARS by Mary Robinette Kowal (book review by Joe Karpierz) THE GLASS BEAD GAME (letter of comment by John Hertz) Five-Way Chili (letter of comment by Neil Ostrove) This Week's Reading (BLACKASS) (book comments by Evelyn C. Leeper) Quote of the Week Co-Editor: Mark Leeper, [email protected] Co-Editor: Evelyn Leeper, [email protected] Back issues at http://leepers.us/mtvoid/back_issues.htm All material is copyrighted by author unless otherwise noted. All comments sent or posted will be assumed authorized for inclusion unless otherwise noted. To subscribe, send mail to [email protected] To unsubscribe, send mail to [email protected] Science Fiction (and Other) Discussion Groups, Films, Lectures, etc. (NJ): July 11, 2019: DESTINATION MOON (1950) & "The Man Who Sold the Moon" by Robert A. Heinlein (novella), Middletown Public Library, 5:30PM http://mtsf.co.nf/ManWhoSoldTheMoon.txt http://mtsf.co.nf/ManWhoSold.pdf July 25, 2019: THE STRANGE CASE OF DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE by Robert Louis Stevenson (1886), Old Bridge Public Library, 7PM August 8, 2019: FIRST MEN IN THE MOON (1964) & THE FIRST MEN IN THE MOON by H. -

Year 3/4 Core List

Year 3/4 core list A Fairy Tale Bill's New Frock By Tony Ross By Anne Fine Bess, a young girl, befriends an old lady who tries Bill wakes up one morning and finds that he is a to convince her to believe in fairies. Over the years girl... they almost imperceptibly change places until old Bess, widowed in World War 2, walks down the street with a youthful Daisy. Black Dog By Levi Pinfold The Hope family lives in a tall narrow house in a A Hen in the Wardrobe snowy wood, the interior of which is depicted in By Wendy Meddour detailed pictures full of the paraphernalia of playful Ramzi’s dad is behaving strangely, sleepwalking & imaginative life. and searching in his son’s wardrobe for a hen or chasing frogs in the pantry. Ramzi and his mum realise that dad is homesick for Algeria so they go there for an extended visit. Can You Whistle, Johanna? By Ulf Stark Chatting with his friend, Berra realises that he is lacking a grandfather, so the pair visit the old Aesop's Fables people’s home so that he can adopt one. A By Beverley Naidoo delightful story dealing with friendship, loss and Aware from her own South African childhood that bereavement. many of the animals in these fables are African, Beverley Naidoo realised that the slave Aesop was himself likely to have been of African origin. Charlotte's Web Danny the Champion of the World By E B White By Roald Dahl Wilbur is the runt of the litter of piglets, saved at first Danny discovers the ‘deep dark secrets’ of the by Fern the farmer's daughter and then by Charlotte adults around him, the chief of which is that most of the spider who weaves wonderful statements about them, including his father, the doctor, the policeman him into her web. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932 CROMPTON, Teresa Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24737/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24737/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932 Teresa Crompton A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2014 Abstract The thesis examines the development of the civil air route between Britain and India from 1918 to 1932. Although an Indian route had been pioneered before the First World War, after it ended, fourteen years would pass before the route was established on a permanent basis. The research provides an explanation for the late start and subsequent slow development of the India route. The overall finding is that progress was held back by a combination of interconnected factors operating in both Britain and the Persian Gulf region. These included economic, political, administrative, diplomatic, technological, and cultural factors. The arguments are developed through a methodology that focuses upon two key theoretical concepts which relate, firstly, to interwar civil aviation as part of a dimension of empire, and secondly, to the history of aviation as a new technology. -

1585672807 With-The-Night-Mail-A

The Project Gutenberg EBook of With The Night Mail, by Rudyard Kipling This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: With The Night Mail A Story of 2000 A.D. (Together with extracts from the comtemporary magazine in which it appeared) Author: Rudyard Kipling Illustrator: Frank X. Leyendecker H. Reuterdahl Release Date: June 16, 2009 [EBook #29135] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITH THE NIGHT MAIL *** Produced by Stephen Hope, Carla Foust, Joseph Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note Minor punctuation errors have been changed without notice. Printer errors have been changed, and they are indicated with a mouse-hover and listed at the end of this book. All other inconsistencies are as in the original. For the "Illustrations" listing the page numbers reflect the position of the illustration in the original text but links link to current position of illustrations. A Table of Contents has been generated for this version. ILLUSTRATIONS WITH THE NIGHT MAIL AERIAL BOARD OF CONTROL BULLETIN NOTES CORRESPONDENCE REVIEWS ADVERTISING SECTION WITH THE NIGHT MAIL A STORY OF 2000 A.D. (TOGETHER WITH EXTRACTS FROM THE CONTEMPORARY MAGAZINE IN WHICH IT APPEARED) BOOKS BY RUDYARD KIPLING BRUSHWOOD BOY, THE CAPTAINS COURAGEOUS COLLECTED VERSE DAY'S WORK, THE DEPARTMENTAL DITTIES AND BALLADS AND BARRACK-ROOM BALLADS FIVE NATIONS, THE JUNGLE BOOK, THE JUNGLE BOOK, SECOND JUST SO SONG BOOK JUST SO STORIES KIM KIPLING BIRTHDAY BOOK, THE LIFE'S HANDICAP; Being Stories of Mine Own People LIGHT THAT FAILED, THE MANY INVENTIONS NAULAHKA, THE (With Wolcott Balestier) PLAIN TALES FROM THE HILLS PUCK OF POOK'S HILL SEA TO SEA, FROM SEVEN SEAS, THE SOLDIER STORIES SOLDIERS THREE, THE STORY OF THE GADSBYS, and IN BLACK AND WHITE STALKY & CO. -

Read Aloud Schedule from Modg KGRD

A Read Aloud Schedule for Kindergarten: Choose the number of columns you think you need. Don't feel you have to do them ALL. PICTURE BOOKS COLLECTIONS BOOK OF VIRTUES/PERRAULT GRIMM 1 Billy and Blaze Peter Rabbit Androcles and the Lion Allerleirauh [or All-Kinds-Of-Fur] 2 Little Bear Make Way for the Ducklings Beauty and the Beast Bremen Town Musicians, The 3 Bedtime for Frances Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel The Cap that Mother Made Cinderella 4 The Story of Babar Curious George Chicken Little Cunning Little Tailor, The 5 Angus and the Ducks Another Potter Jack and the Beanstalk Elves, The [or The Elves and the Shoemaker]* 6 Madeline Another McCloskey Please Fisherman and His Wife, The 7 The Five Chinese Brothers Another Burton The Little Red Hen Frau Holle 8 Stone Soup Another George The Ant and the Grasshopper Frog King, The [Iron Henry; Frog Prince]* 9 The Empty Pot Another Potter The Three Little Pigs Gold-Children, The 10 Petunia Another McCloskey The Tortoise and the Hare Golden Goose, The* 11 The Story About Ping Another Burton The Little Steam Engine Goose-Girl, The 12 Corduroy Another George Try, Try, Again Hans the Hedgehog 13 Millions of Cats Another Potter To the Little Girls that Wriggles Hansel and Gretel* 14 Little Toot Another McCloskey The Crow and the Pitcher King Thrushbeard 15 The Ox Cart Man Another Burton The Sermon to the Birds Little Briar-Rose 16 Another-Billy and Blaze Another George Diamonds and Toads Little Brother and Little Sister 17 Another-Little Bear Another Potter The Velveteen Rabbit Little Red-Cap 18 Another-Frances Another McCloskey Little Boy Blue Peasant's Clever Daughter, The 19 Another-Babar Calico Wonder Horse, Burton (library) St.