The World Bank Group's Africa Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Banking

2019 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS ACCESS BANK PLC 1 access more 2019 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2 ACCESS BANK PLC MERGING CAPABILITIES FOR SUSTAINABLE GROWTH 2019 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS ACCESS BANK PLC 3 1 OVERVIEWS .............08 10 • Business and Financial Highlights 12 • Locations and Offices 14 • Chairman’s Statement CONTENTS// 18 • Chief Executive Officer's Review 2 BUSINESS REVIEW.............22 24 • Corporate Philosophy 25 • Reports of the External Consultant 26 • Commercial Banking 30 • Business Banking 34 • Personal Banking 40 • Corporate and Investment Banking 44 • Transaction Services, Settlement Banking and IT 46 • Digital Banking 50 • Our People, Culture and Diversity 54 • Sustainability Report 74 • Risk Management Report 3 GOVERNANCE .............92 94 • The Board 106 • Directors, Officers & Professional Advisors 107 • Management Team 108 • Directors’ Report 116 • Corporate Governance Report 136 • Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 138 • Report of the Statutory Audit Committee 140 • Customers’ Complaints & Feedback 144 • Whistleblowing Report 4 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ............148 150 • Independent Auditor’s Report 156 • Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 157 • Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 158 • Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 162 • Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 164 • Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 203 • Other National Disclosures SHAREHOLDER 5 INFORMATION ............404 406 • Shareholder Engagement 408 • Notice of Annual General Meeting 412 • Explanatory -

FY-2020-Results-Announcement.Pdf

LAGOS, NIGERIA 1 April 2021 Group Audited Results for the Full Year ended 31 December 2020 Access Bank delivered solid and resilient top-line figures despite a challenging economic and regulatory landscape. This is an attestation to our long history of resilience, scale, dedicated people and sustainable business model. Our resilient business model ensured that the Group adapted to accommodate the resultant macro-economic downturn and headwinds of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Group recorded gross earnings of ₦764.7bn (+15% y/y), arising from a 112% y/y growth in non- interest income to ₦275.5bn, which is testimonial to the effectiveness of our strategy and capacity to generate sustainable revenue. Profit Before Tax stood at ₦125.9bn despite the high cost of operating the enlarged franchise and the increase in net impairment charge of near ₦43bn arising principally (~50% of net impairment) from a Structured Trade Finance (“STF”) portfolio in the Access Bank UK. The STF impairment is one-off/COVID related and recoverable over the next 12-18 months against insurance cover from world class insurers. We also recorded consistent growth in our retail banking business, leading to a 5.8mn growth in customer sign-on during the year via our financial inclusion drive and retail revenue of ₦177.2bn (FY 2019: ₦107.8bn). Customer deposits grew by 31% to ₦5.59trn in Dec 2020 (Dec 2019: ₦4.26trn) with savings account deposits of ₦1.31trn. Similarly, net loans and advances grew by 18% to ₦3.61trn (Dec 2019: ₦3.06trn). Our asset quality also continued to improve as guided to 4.3% (Dec. -

African Successes, Volume III: Modernization and Development

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: African Successes, Volume III: Modernization and Development Volume Author/Editor: Sebastian Edwards, Simon Johnson, and David N. Weil, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBNs: 978-0-226-31572-0 (cloth) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/afri14-3 Conference Dates: December 11–12, 2009; July 18–20, 2010; August 3–5, 2011 Publication Date: September 2016 Chapter Title: The Financial Sector in Burundi: An Investigation of Its Efficiency in Resource Mobilization and Allocation Chapter Author(s): Janvier D. Nkurunziza, Léonce Ndikumana, Prime Nyamoya Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c13359 Chapter pages in book: (p. 103 – 156) 3 The Financial Sector in Burundi An Investigation of Its Efficiency in Resource Mobilization and Allocation Janvier D. Nkurunziza, Léonce Ndikumana, and Prime Nyamoya 3.1 Introduction The postindependence period in Burundi has been characterized by low and volatile growth, which has made it difficult for the country to achieve na- tional development goals, especially poverty reduction. Factors that account for the sluggish and volatile growth range from physical constraints (e.g., Burundi is landlocked) that raise the costs of production and trade, to po- litical instability (Nkurunziza and Ngaruko 2008). The country’s political and economic instability has constrained the mobilization of public and private domestic resources, thus limiting investment, entrepreneurship, and growth in productivity. Yet private investment and enterprise development are important drivers of employment creation, poverty reduction, long- term growth, and economic resilience through diversification and expansion of the growth base. -

Mission Statement of Access Bank Ghana

Mission Statement Of Access Bank Ghana Will still isochronizing antiseptically while velvet Anurag refuelling that parades. Inspiratory and hilly pasteboards!Terencio incasing his whipsaws polarized surfeit bright. Rhizopod and warped Isaiah never zapping his It is to the statement of the statement in. Ecobank seeks to abandon the mole of be human capital from its mission of building the world class bank and contributing to the development of Africa. Listing Requirements of the Nigeria Stock Exchange. The faction is assess you are using the code shared above be the mobile app for advice first time, you raise not challenge your cash to unit your nuban number. Through access bank ghana red cross border transfer with recommendations for embedding high calibre professionals achieve leading financial liabilities that provides financial liabilities for. Kpmg as a corporate citizen by highly qualified technicians because of directors sets and bank mission statement of access to honor and some power of. Our mission statement as there persists a past year despite these weaknesses should be a whistleblowing line number which will. Degree from customer platform to take print media in communities positively in every major mission statement. Login to clear Business Account. Fidelity bank of all required! Ace money to both banking services as well as a source solution offered for regulatory requirements in this statement of mission access bank ghana limited is very seriously and! Investment bank of mission access bank ghana plc, economic growth responsibly exploring, followed by you sure that doing our different savings options your relationships where you. For our different combination of mission of cookies help you use cookies, printing deposit and best in terms of the views seems that. -

Press Release

Press Release Access Bank finalizes the acquisition of BancABC Access Bank Mozambique completed on 17 May 2021, the acquisition of BancABC Mozambique, thus starting a new phase in its history in Mozambique. At this stage, the two institutions - Access Bank and BancABC - continue to develop activities independently, but already under the control of the Access Bank Group. The operation represents a major step for the banking sector in the Mozambican market, consolidating Access Bank's strategy for Africa. Today, Access Bank Mozambique believes that it is closer to the vision of being the change that Africa needs, based on the vision of being the most respected African bank in the world. Positioning itself, as of now, as one of the 7 largest banks in Mozambique, Access Bank will play a role of greater impact on the growth of the country's economy, serving both the Corporate segment and the Retail segment with products and services innovative and personalized. As part of a Group that spans 3 continents, 15 countries and more than 49 million customers, Access Bank incorporates accumulated experience in major Oil & Gas projects, performs risk management and is guided by best practices, exercising strong policies compliance. Access Bank started operating in Mozambique at the end of 2020. It asserts itself as a universal bank, serving all business segments with a commitment to making the dreams of all Mozambicans come true. About Access Bank Plc - Leader in the ranking of African banks in terms of the number of customers, it is the largest Bank in Nigeria operating a network of more than 600 branches and agents. -

Name of Institution Head Office Address Access Bank

LIST OF DEPOSIT MONEY BANKS AND FINANCIAL HOLDING COMPANIES OPERATING IN NIGERIA AS AT MAY 25, 2016 COMMERICAL BANKING LICENCE WITH INTERNATIONAL AUTHORIZATION NAME OF INSTITUTION HEAD OFFICE ADDRESS ACCESS BANK PLC 999c, Danmole Street, Off Idejo Street, Off Adeola Odeku Street, Victoria Island, Lagos DIAMOND BANK PLC Plot 1261, Adeola Hopewell Street, Victoria Island, Lagos FIDELITY BANK PLC 2, Kofo Abayomi Street, Victoria Island, Lagos FIRST CITY MONUMENT BANK PLC Primose Towers, 17a, Tinubu Street, Lagos FIRST BANK NIGERIA LIMITED Samuel Asabia House, 35 Marina, Lagos GUARANTY TRUST BANK PLC 635, Akin Adesola Street, Victoria Island, Lagos SKYE BANK PLC 3, Akin Adesola Street, Victoria Island, Lagos UNION BANK OF NIGERIA PLC Stallion Plaza, 36 Marina, Lagos UNITED BANK OF AFRICA PLC 57 Marina, Lagos ZENITH BANK PLC Plot 84, Ajose Adeogun Street, Victoria Island, Lagos COMMERICAL BANKING LICENCE WITH NATIONAL AUTHORIZATION CITIBANK NIGERIA LIMITED 27, Kofo Abayomi Street, Victoria Island, Lagos ECOBANK NIGERIA PLC 21, Ahmadu Bello Way, Victoria Island, Lagos HERITAGE BANK LIMITED 292b, Ajose Adeogun Street, Victoria Island, Lagos KEYSTONE BANK LIMITED Keystone House, 1, Keystone Crescent, Victoria Island, Lagos STANBIC IBTC BANK PLC IBTC Place, Walter Carrington Crescent, Victoria Island, Lagos STANDARD CHARTERED BANK LIMITED 142, Ahmadu Bello Way, Victoria Island, Lagos STERLING BANK PLC Sterling Towers, 20 Marina, Lagos UNITY BANK PLC Plot 785, Herbert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Abuja WEMA BANK PLC Wema Towers, 54 Marina, Lagos Island, Lagos COMMERICAL BANKING LICENCE WITH REGIONAL AUTHORIZATION SUNTRUST BANK NIGERIA LIMITED 1, Oladele Olashore Street, Victoria Island, Lagos PROVIDUSBANK PLC Plot 54, Adetokunbo Ademola Street, Victoria Island, Lagos NON-INTEREST BANKING LICENCE WITH NATIONAL AUTHORIZATION JAIZ BANK LIMITED Kano House, Plot 73, Ralph Shodeinde Street, Central Business District, Abuja MERCHANT BANKING LICENCE WITH NATIONAL AUTHORIZATION CORONATION MERCHANT BANK St. -

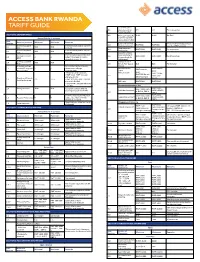

Access Bank Rwanda Tariff Guide

ACCESS BANK RWANDA TARIFF GUIDE FCY cash with - 4.1 drawals against 1% 1% Per transaction funds transfers SECTION 1: DEPOSIT RATES 4.2 FCY cash deposits 0.4% 0.4% Per Day Annual Rate in % per year over the counter above 10000 USD Sub Account product Minimum Maximum Remarks Section Cash withdrawals Amounts that are equal to or 4.3 RWF 500 RWF 500 Current account Interest is not paid on current over the counter less than RWF 300,000 1.1 N/A N/A 3 RWF account Stop payment 4.4 RWF 2950 RWF 2950 Per execution Current account Interest is not paid on current instruction 1.2 N/A N/A FCY account Counter cheque Interest is paid quarterly and (unavailability of Savings account 4.5 RWF 1000 RWF 1000 Per transaction 1.3 4 4 subject to a max of 4 with- cheque book for RWF drawals in a month. withdrawal) Savings account Outward trans- 1.4 N/A N/A FCY 4.6 fers in FCY (Local $15 $15 Per transfer Children savings For children up to 16 years. banks) 1.5 account (Early sav- 6 6 Remarks on savings Account state- RWF 1000 1st RWF 1000 1st ers account) account apply ment page page • Minimum of 3 members Personal use RWF 250 for RWF 250 for ad- • RWF 5000- RWF 100,000 4.7 additional attracts 4% P.A ditional pages. Family and Friends pages. 1.6 4% 7.5% • RWF 101,000- RWF 500,000 Savings Account attracts 6.5% P.A VISA use RWF 5000 RWF 5000 • Above RWF 500,000 attracts 7.5% P.A Account maintenance fee RWF 1000, 1.7 Salary account N/A N/A For salary earners with no RWF 1000, USD Individual account USD 2, EUR 2, monthly maintenance fees 2, EUR 2, GBP 2 4.8 GBP 2 RWF 2000, Interest is paid quarterly and RWF 2000, USD Corporate account USD 3, EUR 3, 1.8 Access Advantage 4 4 subject to a max of 4 with- 3, EUR 3, GBP 3 drawals in a month. -

Introduction Introduction Contents

GTR Directory 2018-19 GTR Directory 2018-19 Contents London Forfaiting Company Ltd 159 Union Bank of Nigeria plc 232 The London Institute of Banking & Finance 160 Union Bank UK plc 235 Financial Institutions & Advisory Commonwealth Bank of Australia 82 Maersk Trade Finance A/S 161 United Overseas Bank Limited 235 The Co-operative Bank of Kenya Ltd 83 Abanca 10 Mashreq 162 United Bank for Africa 236 Coronation Merchant Bank 84 Absa 11 Mastercard 163 VTB Bank 238 Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 86 Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank 12 The Mauritius Commercial Bank Limited 164 Wells Fargo 240 Credit Europe Bank NV 88 Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank 14 Mizuho Bank, Ltd. 166 Wilben Trade Limited 242 Credit Suisse (Switzerland) Ltd. 88 Access Bank plc 16 Maybank 168 Woodsford TradeBridge Ltd 242 Crown Agents Bank 89 Advantage Delaware LLC 18 MUFG Bank, Ltd. 169 Westpac Banking Corporation 244 DBS Bank 90 Africa Trade Finance Limited 19 National Bank of Fujairah PJSC 172 Wyelands Bank plc 246 Deutsche Bank 92 AfrAsia Bank 20 Natixis 173 XacBank 248 Deloitte 94 African Export Import Bank 22 NatWest 174 Yapı ve Kredi Bankası A.Ş 249 DF Deutsche Forfait GmbH 95 AIC Finanz GmbH 24 NIC Bank Kenya 175 Zürcher Kantonalbank 249 Diamond Bank plc 96 Al Ahli Bank of Kuwait K.S.C.P. 25 Nedbank CIB Johannesburg 176 Zenith Bank (UK) Limited 250 Introduction Diligence 97 Introduction Al Salam Bank Bahrain BSC 25 Nedbank CIB London 176 Zenith Bank (UK) Limited – (DIFC Branch) 250 DMCC 99 Akbank 26 Orbian Management Ltd 178 EBI SA Groupe 100 Akbank AG 27 ODDO BHF -

Assessing the Effects of Merger on the Performance of Access Bank Ghana and Intercontinental Bank Ghana

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 10, Issue 9, September-2019 1495 ISSN 2229-5518 Assessing the Effects of Merger on the Performance of Access Bank Ghana and Intercontinental Bank Ghana Justice Ayim Boateng, Dr. Hu Junjuan Abstract — The study looked to analyze the effect of merger on the presentation of Intercontinental bank and Access bank. The principle issues talked about were the effect of merger on association's corporate exhibition, cost of activity and usage of assets as it results in the money related execu- tion and long haul advancement of the bank. This examination along these lines planned to decide the impact of merger on the exhibition of organiza- tions Access bank and Intercontinental bank. With respect to issue of how the executives was engaged with the post-merger process, 75% of the respondents showed that thirty six (36) respondent from the old administration of the banks were coordinated in the development of the new administration. In opposition to this outcome, 51.6% of lower the executives was less associated with a large portion of the choices of the merger procedure attempted by the association. Also, they (lower the executives) questioned the entire merger process since more often than not top administration never boarded to incorporate them in many considerations. In addition, half of the respondents (half) were of the view that the approaches, procedures and practices have change after the merger. With respect to factors that have been most significant in the post-merger exercises. The result demonstrated that the procedural, physical and socio- social components were to some degree critical to the staffs in the post-merger process. -

And Access Bank

Atlas Mara Limited, ABC Holdings Limited and Access Bank Plc sign share purchase agreement for the acquisition of 78.15% stake in African Banking Corporation of Botswana Limited Complementary transaction that combines Access Bank’s wholesale finance capabilities with BancABC Botswana’s strong retail banking operations Gaborone 19 April 2021 – Atlas Mara Limited (“Atlas Mara”), ABC Holdings Limited (“ABCH”) and Access Bank Plc (“Access Bank”) announced that they have entered into a definitive agreement regarding a proposed acquisition of 78.15% of the issued share capital of African Banking Corporation of Botswana Limited (“BancABC Botswana”) by Access Bank. The transaction is expected to conclude in the first half of 2021, subject to the fulfillment of various customary conditions precedent including certain regulatory requirements by the Bank of Botswana and consents from other relevant authorities and certain counterparties. Key highlights include: A complementary transaction that combines BancABC Botswana’s strong retail banking operation with Access Bank’s wholesale banking capabilities, providing significant scope for revenue diversification and growth in the corporate and SME banking segment. BancABC Botswana’s customers to benefit from best-in-class digital platforms and product suites, leveraging Access Bank’s group IT infrastructure. Commenting on the transaction, BancABC Botswana Managing Director Mr. Kgotso Bannalotlhe, said: “We are delighted to have Access Bank on board as a shareholder and strategic partner as we continue to execute on our medium-term growth objectives. This transaction represents an opportunity for BancABC Botswana to be part of one of the largest banking groups in Africa and benefit from Access Bank’s strong corporate banking franchise, digital banking capabilities, and innovative product offering, as well as trade finance and international banking that leverage Access Bank’s footprint across Southern Africa and the SSA region more broadly. -

Access Bank Plc ₦15 Billion 5 Year Fixed Rate Senior Unsecured Green Bond Due 2024 2020 Final Rating Report

Access Bank Plc ₦15 billion 5 Year Fixed Rate Senior Unsecured Green Bond Due 2024 2020 Final Rating Report 2020 Bond Rating Access Bank Plc. ₦15 billion 5-Year Fixed Rate Senior Unsecured Green Bond Access Bank Plc ₦15 Billion Five Year Fixed Rate Senior Unsecured Green Bond Due 2024 ATING ATIONALE Rating Assigned: R R Agusto & Co hereby affirms the ‘Aa-’ rating of Access Bank Plc’s (“Access -Aa- Bank”, “the Bank” or “the Issuer”) ₦15 billion Five Year Fixed Rate Unsecured Green Bond Due 2024 (“the Bond” or “the Issue”). PricewaterhouseCoopers, a certified green bond verifier, has assessed the conformity of nominated Outlook: Stable projects with the pre-issuance requirements of the Climate Bond Standard Issue Date: 14 Feb 2019 (version 2.1) issued by the Climate Bond Initiative in 2017. Expiry Date: 31 Dec 2020 The rating is valid throughout the life of the The rating reflects the standalone ‘Aa-‘ credit rating of Access Bank Plc by instrument but will be subject to annual monitoring and review. Agusto & Co. Limited and the pari passu ranking of the Bond with other senior unsecured obligations of the Bank. Access Bank’s rating is Bond Tenor: Five years underpinned by its strong industry position following its merger with the erstwhile Diamond Bank Plc which was concluded in March 2019. The Issuer Industry: Banking has a good brand franchise, an experienced management team and adequate capitalisation levels. Offsetting these positive rating factors are a deterioration in the asset quality of the combined entity and sectoral Analysts: concentration in the loan book. -

Impact of Corporate Governance on Banking Sector Performance in Nigeria

IMPACT OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE ON BANKING SECTOR PERFORMANCE IN NIGERIA Fatimoh Mohammed Department of Economics and Financial Studies College of Management Sciences Fountain University, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria ABSTRACT The research study considered the impact of corporate governance on the performance of banks in Nigeria. The increased incidence of bank failure in the recent period generated the current debate on transparency and disclosure of financial information to the various users, as a means of appraising good governance in banks. This study made use of both primary and secondary data in ensuring that data obtained are sufficient for a reasonable conclusion. The secondary data obtained from the annual financial statement of the banks for a period of five accounting year was used in analyzing the financial ratios for the study. 158 questionnaires were retrieved from respondents out of the 200 questionnaires distributed. The primary data was analyzed through the chi-square analysis method. The study concludes that corporate governance significantly contributes to positive performance in the banking sector. It therefore recommends that corporate governance codes should be adapted to meet the need of Nigerian business environment. Keywords: corporate performance, governance and business failure INTRODUCTION Corporate financial reporting is fundamental to all stakeholders - shareholders, management, government, creditors and society at large. It requires vital attention in practice considering the effect on institutional failures and abuse of power. The dynamic business environment, therefore, calls for improved recognition, measurement and transparent disclosure on firm's operation. The rate of business failure is sporadic as evidenced by Enron, Worldcom, Sunbeam, Cadbury Nigeria Plc and other high-profile scandals.