Okami Is an Action-Adventure Game Developed by Clover Studios And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indoor Fireworks: the Pleasures of Digital Game Pyrotechnics

Indoor Fireworks: the Pleasures of Digital Game Pyrotechnics Simon Niedenthal Malmö University, School of Arts and Communication Malmö, Sweden [email protected] Abstract: Fireworks in games translate the sensory power of a real-world aesthetic form to the realm of digital simulation and gameplay. Understanding the role of fireworks in games can best be pursued through through a threefold aesthetic perspective that focuses on the senses, on art, and on the aesthetic experience that gives pleasure through the player’s participation in the simulation, gameplay and narrative potentials of fireworks. In games ranging from Wii Sports and Fantavision, to Okami and Assassin’s Creed II, digital fireworks are employed as a light effect, and are also the site for gameplay pleasures that include design and performance, timing and rhythm, and power and awe. Fireworks also gain narrative significance in game forms through association with specific sequences and characters. Ultimately, understanding the role of fireworks in games provokes us to reverse the scrutiny, and to consider games as fireworks, through which we experience ludic festivity and voluptuous panic. Keywords: Fireworks, Pyrotechnics, Digital Games, Game Aesthetics 1. Introduction: On March 9th, 2000, Sony released the fireworks-themed Fantavision (Sony Computer Entertainment 2000) in Japan as one of the very first titles for its then new Playstation 2. Fantavision exhibits many of the desirable qualities for good launch title: simulation properties that show off new graphic capabilities, established gameplay that is quick to grasp, a broad appeal. Though the critical reception for the game was ultimately lukewarm (a 72 rating from Metacritic.com), it is notable that Sony launched its new console with a fireworks game. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

Acquiring Literacy: Techne, Video Games and Composition Pedagogy

ACQUIRING LITERACY: TECHNE, VIDEO GAMES AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY James Robert Schirmer A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2008 Committee: Kristine L. Blair, Advisor Lynda D. Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Richard C. Gebhardt Gary Heba © 2008 James R. Schirmer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristine L. Blair, Advisor Recent work within composition studies calls for an expansion of the idea of composition itself, an increasing advocacy of approaches that allow and encourage students to greater exploration and more “play.” Such advocacy comes coupled with an acknowledgement of technology as an increasingly influential factor in the lives of students. But without a more thorough understanding of technology and how it is manifest in society, any technological incorporation is almost certain to fail. As technology advances along with society, it is of great importance that we not only keep up but, in fact, reflect on process and progress, much as we encourage students to do in composition courses. This document represents an exercise in such reflection, recognizing past and present understandings of the relationship between technology and society. I thus survey past perspectives on the relationship between techne, phronesis, praxis and ethos with an eye toward how such associative states might evolve. Placing these ideas within the context of video games, I seek applicable explanation of how techne functions in a current, popular technology. In essence, it is an analysis of video games as a techno-pedagogical manifestation of techne. With techne as historical foundation and video games as current literacy practice, both serve to improve approaches to teaching composition. -

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What Is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura This ritual dance is performed to purify the kagura site, with the performer carrying a Since ancient times, people in Japan have believed torimono (prop) while remaining unmasked. Various props are carried while the dance is that gods inhabit everything in nature such as rocks and History of Izumo Kagura Shichiza performed without wearing any masks. The name shichiza is said to derive from the seven trees. Human beings embodied spirits that resonated The Shimane Prefecture is a region which boasts performance steps that comprise it, but these steps vary by region. and sympathized with nature, thus treasured its a flourishing, nationally renowned kagura scene, aesthetic beauty. with over 200 kagura groups currently active in the The word kagura is believed to refer to festive prefecture. Within Shimane Prefecture, the regions of rituals carried out at kamikura (the seats of gods), Izumo, Iwami, and Oki have their own unique style of and its meaning suggests a “place for calling out and kagura. calming of the gods.” The theory posits that the word Kagura of the Izumo region, known as Izumo kamikuragoto (activity for the seats of gods) was Kagura, is best characterized by three parts: shichiza, shortened to kankura, which subsequently became shikisanba, and shinno. kagura. Shihoken Salt—signifying cleanliness—is used In the first stage, four dancers hold bells and hei (staffs with Shiokiyome paper streamers), followed by swords in the second stage of Sada Shinno (a UNESCO Intangible Cultural (Salt Purification) to purify the site and the attendees. -

Folha De Rosto ICS.Cdr

“For when established identities become outworn or unfinished ones threaten to remain incomplete, special crises compel men to wage holy wars, by the cruellest means, against those who seem to question or threaten their unsafe ideological bases.” Erik Erikson (1956), “The Problem of Ego Identity”, p. 114 “In games it’s very difficult to portray complex human relationships. Likewise, in movies you often flit between action in various scenes. That’s very difficult to do in games, as you generally play a single character: if you switch, it breaks immersion. The fact that most games are first-person shooters today makes that clear. Stories in which the player doesn’t inhabit the main character are difficult for games to handle.” Hideo Kojima Simon Parkin (2014), “Hideo Kojima: ‘Metal Gear questions US dominance of the world”, The Guardian iii AGRADECIMENTOS Por começar quero desde já agradecer o constante e imprescindível apoio, compreensão, atenção e orientação dos Professores Jean Rabot e Clara Simães, sem os quais este trabalho não teria a fruição completa e correta. Um enorme obrigado pelos meses de trabalho, reuniões, telefonemas, emails, conversas e oportunidades. Quero agradecer o apoio de família e amigos, em especial, Tia Bela, João, Teté, Ângela, Verxka, Elma, Silvana, Noëmie, Kalashnikov, Madrinha, Gaivota, Chacal, Rita, Lina, Tri, Bia, Quelinha, Fi, TS, Cinco de Sete, Daniel, Catarina, Professor Albertino, Professora Marques e Professora Abranches, tanto pelas forças de apoio moral e psicológico, pelas recomendações e conselhos de vida, e principalmente pela amizade e memórias ao longo desta batalha. Por último, mas não menos importante, quero agradecer a incessante confiança, companhia e aceitação do bom e do mau pela minha Twin, Safira, que nunca me abandonou em todo o processo desta investigação, do meu caminho académico e da conquista da vida e sonhos. -

Momotaro (The Peach Boy) and the Spirit of Japan: Concerning the Function of a Fairy Tale in Japanese Nationalism of the Early Showa Age*

Klaus Antoni Universitdt Hamburg Momotaro (The Peach Boy) and the Spirit of Japan: Concerning the Function of a Fairy Tale in Japanese Nationalism of the Early Showa Age* Abstract This article is concerned with a famous Japanese fairy tale, Momotaro, which was used during the war years in school readers as a primary part of nationalistic pro paganda. The tale and its central motif are analyzed and traced back through history to its earliest forms. Heroes from legend and history offered perfect identification patterns and images for the propagation of state ideals that were spread through education, the military, and war propaganda. Momotaro subtly- transmitted to young school pupils that which official Japan looked upon as the goal of its ideological education: through a fairy tale the gate to the “ Japanese spirit ” was opened. Key words: Momotaro — Japanese spirit — war propaganda Ryukyu Islands Asian Folklore Studies> Volume 50,1991:155-188. N a t io n a l is m a n d F o l k T r a d it io n in M o d e r n J a p a n F oundations of Japanese N ationalism APAN is a land rich in myths, legends, and fairy tales. It pos sesses a large store of traditional oral and literary folk literature, J which has not been accounted for or even recognized in the West. The very earliest traditional written historical documents contain narratives, themes, and motifs that express this rich tradition. Even though the Kojiki of the year 712, the oldest extant written source, was conceived of as a historical work at the time, it is a collection of pure myths, or at least the beginning portions are. -

The Symbol of the Dragon and Ways to Shape Cultural Identities in Institute Working Vietnam and Japan Paper Series

2015 - HARVARD-YENCHING THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN INSTITUTE WORKING VIETNAM AND JAPAN PAPER SERIES Nguyen Ngoc Tho | University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE 1 CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN VIETNAM AND JAPAN Nguyen Ngoc Tho University of Social Sciences and Humanities Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City Abstract Vietnam, a member of the ASEAN community, and Japan have been sharing Han- Chinese cultural ideology (Confucianism, Mahayana Buddhism etc.) and pre-modern history; therefore, a great number of common values could be found among the diverse differences. As a paddy-rice agricultural state of Southeast Asia, Vietnam has localized Confucianism and absorbed it into Southeast Asian culture. Therefore, Vietnamese Confucianism has been decentralized and horizontalized after being introduced and accepted. Beside the local uniqueness of Shintoism, Japan has shared Confucianism, the Indian-originated Mahayana Buddhism and other East Asian philosophies; therefore, both Confucian and Buddhist philosophies should be wisely laid as a common channel for cultural exchange between Japan and Vietnam. This semiotic research aims to investigate and generalize the symbol of dragons in Vietnam and Japan, looking at their Confucian and Buddhist absorption and separate impacts in each culture, from which the common and different values through the symbolic significances of the dragons are obviously generalized. The comparative study of Vietnamese and Japanese dragons can be enlarged as a study of East Asian dragons and the Southeast Asian legendary naga snake/dragon in a broader sense. The current and future political, economic and cultural exchanges between Japan and Vietnam could be sped up by applying a starting point at these commonalities. -

Color and Games

Spring 2021 DIKULT350 Candidate no: 109. Color and games The effect of colors in the video game multimodality Master's Thesis in Digital Culture Spring 2021 Supervisor: Daniel Jung University of Bergen Candidate no: 109 DIKULT350 Page i Spring 2021 DIKULT350 Candidate no: 109. Acknowledgment This study was completed at the Department of Linguistic, Literary, and Aesthetic Studies at the University of Bergen. I would first like to thank my thesis supervisor Daniel Jung for giving me great and valuable feedback and pushing me to make my goals even clearer. His feedback did help me to get a goal that was better than my original. I will also thank the whole Faculty of Humanities and the professors at Digital culture. This also includes Fulbright, Professor Chris Ingraham, since he helped me to form my master ideas at the start. After that, I will also thank my brother Joakim Andersson and my great friend Malin Jakobsen since they helped a lot with proofreading and helping me with valuable feedback. Thanks to Simon Dreetz Holt for helping me catch all Pokémon's and inspire me to make changes to my text. I will also say thank you to Sunnhorldand folhøgskole and Markus Lange. Thanks for letting me lecture your students. Also, thanks to det Akademiske Kvarteret for free coffee. Solveig Møster gets a special thanks for the interview that is in this thesis. Thanks for giving me your time and knowledge. My last thanks will go to my close friends called "the lads." Thanks for helping me through the time with this and giving me feedback Finally, I want to thank every person who helps me with my project. -

MICROMANIA GAMES SHOW 08 LE SALON DU JEU VIDEO - JOUR J-5 31 Octobre Au 3 Novembre – Porte De Versailles – Paris

MICROMANIA GAMES SHOW 08 LE SALON DU JEU VIDEO - JOUR J-5 31 Octobre au 3 Novembre – Porte de Versailles – Paris Le seul Salon des Jeux Vidéo qui permet de découvrir vraiment toutes les nouveautés de Noël avant l'heure grâce à des mises en scène spectaculaires. Le MICROMANIA GAMES SHOW, confirme le soutien de l’ensemble de l’industrie. AVEC UNE GRANDE QUALITE de MISE EN SCENE et UN SAVOIR FAIRE IMPECABLE, LE MGS A POUR OBJECTIF DE COMBLER SES VISITEURS. Théâtralisés à l’extrême, les stands sont un véritable parc de loisirs des jeux vidéo. Cette année, le MGS monte encore d’un cran en qualité. Le MGS - Véritable salon du jeu vidéo - relève ainsi le challenge de présenter les jeux de fin d’année et de 2009 d’une façon hyper qualitative dans une ambiance incroyable. « Ce qui compte ce n’est pas de faire un maximum d’entrées, mais que 100 % des participants aient le sourire en repartant» affirme Pierre Cuilleret, le président de Micromania. Grâce au soutien de toute l’industrie, le challenge est relevé. Unique en son genre, jamais égalé, ni en France, ni en Europe, le savoir faire du MGS profite de ses 8 années d’expérience et des 25 ans de la collaboration de MICROMANIA avec l’industrie des jeux vidéo. Le MGS offre aux visiteurs des grands espaces. Des stands avec plus de 600 consoles et des animations spectaculaires, une ambiance unique pour faire découvrir l’incroyable monde du MGS de la meilleure façon qu’il soit. Julien SIMONNET - [email protected] - 01 55 94 86 23 - 06 60 25 37 71 Raphaël WOLFF - [email protected] - 01 55 94 86 23 DES STARS DES JEUX VIDEO La salle de démonstration du MGS, avec son Vidéo Projecteur Full HD sur un écran 6x4, aura droit à des présentations de jeux par les développeurs eux même. -

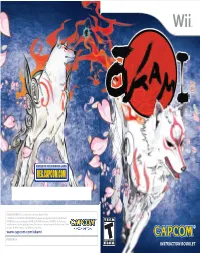

Instruction Booklet

CAPCOM ENTERTAINMENT, INC., 800 Concar Drive, Suite 300, San Mateo, CA 94402 © CAPCOM CO., LTD. 2006, 2008 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Wii development by Ready At Dawn Studios LLC. CAPCOM and the CAPCOM LOGO are registered trademarks of CAPCOM CO., LTD. ŌKAMI is a trademark of CAPCOM CO., LTD. The typefaces included herein are solely developed by DynaComware. The rating icon is a registered trademark of the Entertainment Software Association. All other trademarks are owned by their respective owners. www.capcom.com/okami PRINTED IN USA INSTRUCTION BOOKLET ESRB on Front: 14 x 21 mm OKAMI: Wii Manual Cover - Round 5 Prepared by Eclipse Advertising on: February 28, 2008 PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT The Official Seal is your assurance that this product is licensed or manufactured by HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. Nintendo. Always look for this seal when buying video game systems, accessories, games and related products. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. Dolby, Pro Logic, and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. Manufactured under license from Dolby Laboratories. WARNING – Seizures This game is presented in Dolby Pro Logic II. To play games that carry the Dolby Pro Logic II logo in surround sound, you will need a Dolby Pro Logic II, Dolby Pro Logic or Dolby Pro Logic IIx receiver. These • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or receivers are sold separately. -

4. the Street Fighter Lady

4. The Street Fighter Lady Invisibility and Gender in Game Composition Andy Lemon and Hillegonda C Rietveld Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association December 2019, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 107-133. ISSN 2328-9422 © The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — NonCommercial –NonDerivative 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/ 2.5/). IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are property of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights ABSTRACT The international success of Japanese game design provides an example of the invisibility of female game composers, as well as of gendered identification in game music production and sound design. Yoko Shimomura, the female composer who produced the iconic soundtrack for the 1991 arcade game, Street Fighter II (Capcom 1991), seems to have been invisible to game developers and music producers, which is partly due to the way in which the game is credited as a team effort. Regardless of their personal gender identity, game composers respond to themed briefs by 107 108 The Street Fighter Lady drawing on transnational musical ideas and gendered stereotypes that resonate with the Global Popular. Game music, as imagined as suitable for hyper-masculine game arcades, seems to draw on a masculinist aesthetic developed in Hollywood compositions. In turn, Street Fighter II’s music and the competitive game culture of arcade fighting games has been interwoven with masculinist music scenes of hip-hop and grime. The discussion of the music of Street Fighter II and the musical versions it inspired, nevertheless highlights that although seemingly simplified gendered stereotypes are reproduced within the game, gender identification itself can be complex within the context of game music composition. -

Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games

arts Article Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games Carme Mangiron Department of Translation, Interpreting and East Asian Studies, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Abstract: Japanese video games have entertained players around the world and played an important role in the video game industry since its origins. In order to export Japanese games overseas, they need to be localized, i.e., they need to be technically, linguistically, and culturally adapted for the territories where they will be sold. This article hopes to shed light onto the current localization practices for Japanese games, their reception in North America, and how users’ feedback can con- tribute to fine-tuning localization strategies. After briefly defining what game localization entails, an overview of the localization practices followed by Japanese developers and publishers is provided. Next, the paper presents three brief case studies of the strategies applied to the localization into English of three renowned Japanese video game sagas set in Japan: Persona (1996–present), Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (2005–present), and Yakuza (2005–present). The objective of the paper is to analyze how localization practices for these series have evolved over time by looking at industry perspectives on localization, as well as the target market expectations, in order to examine how the dialogue between industry and consumers occurs. Special attention is given to how players’ feedback impacted on localization practices. A descriptive, participant-oriented, and documentary approach was used to collect information from specialized websites, blogs, and forums regarding localization strategies and the reception of the localized English versions.